Shepherdia argentea

Shepherdia argentea, commonly called silver buffaloberry,[2] bull berry, or thorny buffaloberry, is a species of Shepherdia in the Russian olive family.

| Shepherdia argentea | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Elaeagnaceae |

| Genus: | Shepherdia |

| Species: | S. argentea |

| Binomial name | |

| Shepherdia argentea | |

| |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

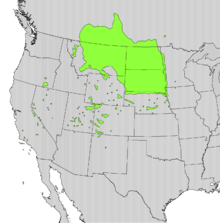

It is native to central and western North America, from the Prairie Provinces of Canada (Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba) southwards in the United States as far as Ventura County in California, as well as northern Arizona, and northwestern New Mexico.[3][4]

Description

Shepherdia argentea is a deciduous shrub growing from 2–6 metres (6.6–19.7 ft) tall. The leaves are arranged in opposite pairs (rarely alternately arranged), 2–6 cm long, oval with a rounded apex, green with a covering of fine silvery, silky hairs, more thickly silvery below than above.[5]

The flowers are pale yellow, with four sepals but no petals.[5]

The fruit is a bright red fleshy drupe 5 mm in diameter; it is edible but with a rather bitter taste.[6] Two cultivars, 'Xanthocarpa' and 'Goldeneye', form yellow fruit.[5]

Ecology

The berry is one of the mainstays of the diet of the sharp-tailed grouse, the provincial bird of Saskatchewan. The foliage provides important forage for mule deer[7] and white-tailed deer.[8] The shrub's thorny branches and thicket forming habit provide a shelter for many small animal species and an ideal nesting site for songbirds.[9] Over the extent of its range, the buffaloberry is an important species in a variety of ecological communities. For example, in the shrub-grassland communities of North Dakota it is found growing with many native grasses, while in riparian woodlands of Montana and Western North Dakota it can be found in plant communities dominated by green ash.[10]

Uses

Like the Canada buffaloberry, Sheperdia argentea has been used historically as a food, medicine, and dye.[11] Its various uses including the treatment of stomach troubles and in coming-of-age ceremonies for girls.[12]

In the Great Basin, the berries were eaten raw and dried for winter use, but more often cooked into a flavoring sauce for bison meat.[13] The buffaloberry has been a staple food to some American Indians, who ate the berries in puddings, jellies, and in raw or dried form.[14] The Gosiute Shoshone name for the plant is añ-ka-mo-do-nûp.[15]

References

- Tropicos, Shepherdia argentea (Pursh) Nutt.

- "Shepherdia argentea". Natural Resources Conservation Service PLANTS Database. USDA. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- "Shepherdia argentea". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- Biota of North America Program 2014 county distribution map

- Brand, Mark H. "Shepherdia argentea". UConn Plant Database of Trees, Shrubs, and Vines. University of Connecticut Horticulture. Archived from the original on 2013-12-06. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- Jepson Flora: Shepherdia argentea

- "Silver Buffaloberry" (PDF). N.D. Tree Handbook. NDSU Agriculture. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- R.J. Mackie, R.F. Batchelor, M.E. Majerus, J.P. Weigand, and V.P. Sundberg. "Silver Buffaloberry (Shepherdia argentea)". Habitat Management Suggestions for Selected Wildlife Species. Montana State University, Animal and Range Sciences. Archived from the original on 2010-06-10. Retrieved 2 December 2013.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Silver Buffaloberry" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- Esser, Lora L. "Shepherdia argentea". Fire Effects Information System. USDA Forest Service. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- Benfer, Adam. "Buffaloberry". Foods Indigenous to the Western Hemisphere. Kansas University American Indian Health and Diet Project. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- Burns Kraft, TF; Dey, M; Rogers, RB; Ribnicky, DM; Gipp, DM; Cefalu, WT; Raskin, I; Lila, MA (23 January 2008). "Phytochemical Composition and Metabolic Performance Enhancing Activity of Dietary Berries Traditionally Used by Native North Americans". J Agric Food Chem. 56 (3): 654–60. doi:10.1021/jf071999d. PMC 2792121. PMID 18211018.

- William C. Sturtevant, ed. (1986). Handbook of North American Indians: Great Basin. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 9780160045813. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- Betty B. Derig and Margaret C. Fuller (2001). Wild Berries of the West. Missoula, Montana: Mountain Press Publishing Company. p. 119. ISBN 0-87842-433-4.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Chamberlin, Ralph Vary (1911). "The Ethno-botany of the Gosiute Indians of Utah" (PDF). Memoirs of the American Anthropological Association Vol II, part 5. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Shepherdia argentea |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1905 New International Encyclopedia article about Shepherdia argentea. |

- Jepson Manual Treatment for Shepherdia argentea

- University of Michigan—Dearborn: Native American Ethnobotany of Silver buffaloberry

- United States Department of Agriculture, National Forest Service Fire Ecology

- Shepherdia argentea — Calphotos Photo gallery, University of California