Shahr-e Sukhteh

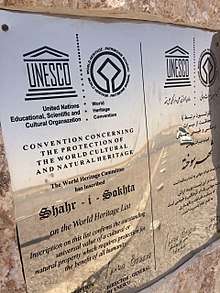

Shahr-e Sukhteh (Persian: شهر سوخته, meaning "[The] Burnt City"), also spelled as Shahr-e Sūkhté and Shahr-i Sōkhta, is an archaeological site of a sizable Bronze Age urban settlement, associated with the Jiroft culture. It is located in Sistan and Baluchistan Province, the southeastern part of Iran, on the bank of the Helmand River, near the Zahedan-Zabol road. It was placed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in June 2014.[1][2]

شهر سوخته | |

| |

Location in Iran | |

| Location | Sistan and Baluchestan Province, Iran |

|---|---|

| Region | Sistan |

| Coordinates | 30°35′43″N 61°19′35″E |

| History | |

| Abandoned | 2100 BCE |

| Periods | Bronze Age |

| Cultures | Jiroft culture |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | In ruins |

| Public access | yes ( 08:00 -19:00) |

| Official name | Shahr-i Sokhta |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iii, iv |

| Designated | 2014 (38th session) |

| Reference no. | 1456 |

| Region | Asia-Pacific |

The reasons for the unexpected rise and fall of the city are still wrapped in mystery. Artifacts recovered from the city demonstrate a peculiar incongruity with nearby civilizations of the time and it has been speculated that Shahr-e-Sukhteh might ultimately provide concrete evidence of a civilization east of prehistoric Persia that was independent of ancient Mesopotamia.

Archaeology

Covering an area of 151 hectares, Shahr-e Sukhteh was one of the world’s largest cities at the dawn of the urban era. In the western part of the site is a vast graveyard, measuring 25 ha. It contains between 25,000 and 40,000 ancient graves.[3]

The settlement appeared around 3200 BCE. The city had four stages of civilization and was burnt down three times before being abandoned in 1800 BCE.

| Period | Dating | Settlement size |

|---|---|---|

| I | 3200–2800 BCE | 10–20 ha |

| II | 2800–2500 | 45 ha |

| III | 2500–2300 | 100 ha |

| IV | 2300–2100 |

The site was discovered and investigated by Aurel Stein in the early 1900s.[4][5]

Beginning in 1967, the site was excavated by the Istituto italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente (IsIAO) team led by Maurizio Tosi. That work continued until 1978.[6][7][8] After a gap, work at the site was resumed by the Iranian Cultural Heritage and Tourism Organization team led by SMS Sajjadi.[9][10] New discoveries are reported from time to time.[11]

Most of the material discovered is dated to the period of c. 2700-2300 BCE. The discoveries indicate that the city was a hub of trading routes that connected Mesopotamia and Iran with the Central Asian and Indian civilizations, and as far away as China.

During the Period I, Shahr-e Sukhteh already shows close connections with the sites in southern Turkmenistan, with the Kandahar region of Afghanistan, the Quetta valley, and the Bampur valley in Iran. Also, there are the connections with the Proto-Elamite cities of Ḵuzestān and Fārs. During Period II, Shahr-e Sukhteh was also in contact with the pre-Harappan centers of the Indus valley, and the contacts with the Bampur valley continued.[12]

Shahdad is another related big site that is being excavated. Some 900 Bronze Age sites have been documented in the Sistan Basin, the desert area between Afghanistan and Pakistan.[13]

Helmand and Jiroft cultures

The Helmand culture of western Afghanistan was a Bronze Age culture of the 3rd millennium BCE. Scholars link it with the Shahr-i Sokhta, Mundigak, and Bampur sites.

This civilization flourished between 2500 and 1900 BCE, and may have coincided with the great flourishing of the Indus Valley Civilization. This was also the final phase of Periods III and IV of Shahr-i Sokhta, and the last part of Mundigak Period IV.[14]

Thus, the Jiroft and Helmand cultures are closely related. The Jiroft culture flourished in the eastern Iran, and the Helmand culture in western Afghanistan at the same time. In fact, they may represent the same cultural area. The Mehrgarh culture, on the other hand, is far earlier.

Finds

- A recent discovery is a unique marble cup, which was found on 29 December 2014.[15]

- In January 2015, a Bronze Age piece of leather adorned with drawings was discovered [16]

- In December 2006, archaeologists discovered the world's earliest known artificial eyeball.[17] It has a hemispherical form and a diameter of just over 2.5 cm (1 inch). It consists of very light material, probably bitumen paste. The surface of the artificial eye is covered with a thin layer of gold, engraved with a central circle (representing the iris) and gold lines patterned like sun rays. The female whose remains were found with the artificial eye was 1.82 m tall (6 feet), much taller than ordinary women of her time. On both sides of the eye are drilled tiny holes, through which a golden thread could hold the eyeball in place. Since microscopic research has shown that the eye socket showed clear imprints of the golden thread, the eyeball must have been worn during her lifetime. The woman's skeleton has been dated to between 2900 and 2800 BCE.[18]

- The oldest known backgammon, dice and caraway seeds, together with numerous metallurgical finds (e.g. slag and crucible pieces), are among the finds which have been unearthed by archaeological excavations from this site.

- Other objects found at the site include a human skull which indicates the practice of brain surgery and an earthen goblet depicting what archaeologists consider to be the first animation.[19]

- Paleoparasitological studies suggest that inhabitants were infested by nematodes of the genus Physaloptera, a rare disease.[20]

See also

- Sistan Basin

- Cities of the Ancient Near East

- Mundigak

References

- "Shahr-i Sokhta". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. UNESCO. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- "Twenty six new properties added to World Heritage List at Doha meeting". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. UNESCO. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- Sandro Salvatori And Massimo Vidale, Shahr-I Sokhta 1975-1978: Central Quarters Excavations: Preliminary Report, Istituto italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente, 1997, ISBN 978-88-6323-145-8

- Aurel Stein, Innermost Asia. Detailed Report of explorations in Central Asia, Kansu and Eastern Iran, Clarendon Press, 1928

- Aurel Stein, An Archaeological Journey in Western Iran, The Geographical Journal, vol. 92, no. 4, pp. 313-342, 1938

- Maurizio Tosi, Excavations at Shahr-i Sokhta. Preliminary Report on the Second Campaign, September–December 1968, East and West, vol. 19/3-4, pp. 283-386, 1969

- Maurizio Tosi, Excavations at Shahr-i Sokhta, a Chalcolithic Settlement in the Iranian Sistan. Preliminary Report on the First Campaign, East and West, vol. 18, pp. 9-66, 1968

- P. Amiet and M. Tosi, Phase 10 at Shahr-i Sokhta: Excavations in Square XDV and the Late 4th Millennium B.C. Assemblage of Sistan, East and West, vol. 28, pp. 9-31, 1978

- S. M. S. Sajjadi et al., Excavations at Shahr-i Sokhta. First Preliminary Report on the Excavations of the Graveyard, 1997-2000, Iran, vol. 41, pp. 21-97, 2003

- S.M.S. Sajjadi & Michèle Casanova, Sistan and Baluchistan Project: Short Reports on the Tenth Campaign of Excavations at Shahr-I Sokhta, Iran, vol. 46, iss. 1, pp. 307-334, 2008

- "CHN - News". archive.org. 13 March 2012. Archived from the original on 13 March 2012. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- Pierfrancesco Callieri, Bruno Genito (2012), ITALIAN EXCAVATIONS IN IRAN www.iranicaonline.org

- Andrew Lawler, The World in Between Volume 64 Number 6, November/December 2011 archaeology.org

- Jarrige, J.-F., Didier, A. & Quivron, G. (2011) Shahr-i Sokhta and the Chronology of the Indo-Iranian Borderlands. Paléorient 37 (2) : 7-34 academia.edu

- "Unique marble cup, other discoveries in Burnt City". mehrnews.com. 29 December 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- "Ancient Piece of Leather Found in Burnt City". newhistorian.com. 15 January 2015. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- "3rd Millennium BC Artificial Eyeball Discovered in Burnt City". Cultural Heritage News Agency of Iran. 10 December 2006. Archived from the original on 11 April 2012.

- "5,000-Year-Old Artificial Eye Found on Iran-Afghan Border". foxnews.com. 20 February 2007. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- Foltz, Richard C. (2016). Iran in World History. Oxford University Press. p. 6. ISBN 9780199335503.

- Makki, Mahsasadat; Dupouy-Camet, Jean; Seyed Sajjadi, Seyed Mansour; Moravec, František; Reza Naddaf, Saied; Mobedi, Iraj; Malekafzali, Hossein; Rezaeian, Mostafa; Mohebali, Mehdi; Kargar, Faranak; Mowlavi, Gholamreza (2017). "Human spiruridiasis due to Physaloptera spp. (Nematoda: Physalopteridae) in a grave of the Shahr-e Sukhteh archeological site of the Bronze Age (2800–2500 BC) in Iran". Parasite. 24: 18. doi:10.1051/parasite/2017019. ISSN 1776-1042. PMC 5467177. PMID 28573969.

Further reading

- F. H. Andrewa, Painted Neolithic Pottery in Sistan discovered by Sir Aurel Stein, The Burlington Magazine, vol. 47, pp. 304–308, 1925

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shahr-e Sukhteh. |