Shahab-3

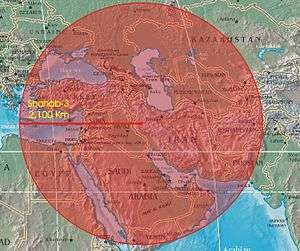

The Shahab-3 (Persian: Šahâb 3; meaning "meteor") is a quad-exhaust liquid-propelled medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) developed by Iran and based on the North Korean Nodong-1.[9][10] The Shahab-3 has a range of 1,000 kilometres (620 mi); a MRBM variant can now reach 2,000 kilometres (1,200 mi) (can hit targets as far as Israel, Egypt, Romania, Bulgaria and Greece).[11] It was tested from 1998 to 2003 and added to the military arsenal on 7 July 2003, with an official unveiling by Ayatollah Khamenei on July 20. With an accuracy of 140 m CEP, the Shahab-3 missile is primarily effective against large, soft targets (like cities). Given the Shahab-3’s payload capacity, it would likely be capable of delivering nuclear warheads. According to the IAEA, Iran in the early 2000s may have explored various fuzing, arming and firing systems to make the Shahab-3 more capable of reliably delivering a nuclear warhead.[12]

| Shahab-3 | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Type | Strategic MRBM |

| Service history | |

| In service | 2003–present |

| Used by | Iran |

| Production history | |

| Manufacturer | Iran |

| Variants | A,B,C,D |

| Specifications | |

| Diameter | 1.2 m (3 ft 11 in) |

| Warhead | One (1,200 kg or 2,600 lb) at 1,000-2,000 km[1]– five cluster munition warheads in new models (280 kg or 620 lb) each warhead, each warhead can target different destinations. |

| Engine | Liquid propellant rocket[2] |

Operational range | 1,000 km (620 mi)[3]-2,000 km (1,200 mi) [4] (Shahab-3 ER)[5] |

| Flight altitude | 400 km[6] |

| Maximum speed | 2.4 km/s at altitude of 10–30 km in final stage which is about mach 7[7] |

Guidance system | inertial navigation system |

| Accuracy | 140 m Circular error probable[8] |

The forerunners to this missile include the Shahab-1 and Shahab-2. In 2007, the then-Iranian Defence Minister Admiral Shamkhani has denied that Iran plans to develop a Shahab-4. Some successors to the Shahab have longer range and are also more maneuverable.[13][14][15]

Operating under the Sanam Industrial Group (Department 140), which is part of the Defense Industries Organization of Iran, the Shahid Hemmat Industrial Group (SHIG), led the development of the Shahab missile.[16]

US Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center estimates that as of June 2017 fewer than 50 launchers were operationally deployed.[17]

Variants

Shahab is the name of a class of Iranian missiles, service time of 1988–present, which comes in six variants: Shahab-1, Shahab-2, Shahab-3, Shahab-4, Shahab-5, and Shahab-6.

Shahab-3B

The Shahab-3B differs from the basic production variant. It has improvements to its guidance system and warhead with a greater range, a few small changes on the missile body, and a new re-entry vehicle whose terminal guidance system and rocket-nozzle steering method are completely different from the Shahab-3A's spin-stabilized re-entry vehicle.

The new re-entry vehicle uses a triconic aeroshell geometry (or "baby bottle" design) which improves the overall lift to drag ratio for the re-entry vehicle. This allows greater range maneuverability which can result in better precision. The triconic design also reduces the overall size of the warhead from an estimated 1 metric ton (2,200 lb) to 700 kg (1,500 lb).

The rocket-nozzle control system allows the missile to change its trajectory several times during re-entry and even terminal phase, effectively preventing interceptor guidance via trajectory prediction by early warning radar—a method nearly all long range ABM systems use. As a high-speed ballistic missile and pre-mission fueling capability, the Shahab-3 has an extremely short launch/impact time ratio. This means that the INS/gyroscope guidance would also remain relatively accurate until impact (important, given the fact that the gyroscopes tend to lose accuracy with longer flights). The CEP is estimated to be at 30–50 metres (98–164 ft) or less.[18] However, the accuracy of the missile is largely speculative and cannot be confidently predicted for wartime situations.[19]

These improvements would increase the Shahab-3B's survivability against ABM systems such as Israel's Arrow 2 missile defence system (though its ability to overcome Arrow is very questionable) as well as being used for precision attacks against high-value targets such as command, control, and communications centres.

Shahab-3C and D

Little is known about Shahab-3C and Shahab-3D. From what can be gathered, the missiles have an improved precision, navigation system, and a longer range. The missiles were indigenously developed, and are being mass-produced. Iran had in 2008 a production capacity of 70 units per year.[20]

Galleries

- Shahab 3 image gallery

Shahab 3 engine

Shahab 3 engine With truck-mounted launcher, 2010 Military Day Parade

With truck-mounted launcher, 2010 Military Day Parade

- Shahab 3 launch day 3 July 2012

.jpg) Operational pre-launch

Operational pre-launch.jpg) Lift-off (cropped)

Lift-off (cropped) Lift-off

Lift-off.jpg) Flight (cropped)

Flight (cropped) Flight

Flight

- Shahab 3 artwork

Artist's conception

Artist's conception Artist's conception

Artist's conception Artist's conception

Artist's conception

History and tests

The Shahab-3 was first seen in public on 25 September 1998, in Azadi Square, Tehran, in a parade held to commemorate the Iranian Sacred Defence Week.

Iran has conducted at least six test flights of the Shahab-3. During the first one, in July 1998, the missile reportedly exploded in mid-air during the latter portion of its flight; U.S. officials wondered whether the test was a failure or the explosion was intentional. A second, successful test took place in July 2000.[9] In September 2000, Iran conducted a third test, in which the missile reportedly exploded shortly after launch. In May 2002, Iran conducted another successful test, leading then-Iranian Defense Minister Ali Shamkhani to say the test improved the Shahab-3's "power and accuracy". Another successful test reportedly occurred in July 2002. On 7 July 2003, the foreign ministry spokesman said that Iran had completed a final test of the Shahab 3 "a few weeks ago" that was "the final test before delivering the missile to the armed forces", according to a New York Times report.[21]

On 9 November 2004, Shamkhani said Iran could mass-produce the missile.[22]

On 2 November 2006, Iran fired unarmed missiles to begin 10 days of military war games. Iranian state television reported "dozens of missiles were fired including Shahab-2 and Shahab-3 missiles. The missiles had ranges from 300 km (190 mi) to up to 2,000 km (1,200 mi)...Iranian experts have made some changes to Shahab-3 missiles installing cluster warheads in them with the capacity to carry 1,400 bombs". These launches come after some United States-led military exercises in the Persian Gulf on 30 October 2006, meant to train for blocking the transport of weapons of mass destruction.[23]

2008 Great Prophet III test

On 8 July 2008,[24] Iran test fired a non-upgraded version of the Shahab-3 as one of 9 medium- and long-range missiles launched as part of the Great Prophet III exercise, within a few weeks of a recently concluded military exercise by Israel.[25]

Other missiles fired include the surface-to-surface Fateh-110 and Zelzal missiles.[26] Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps air and naval units conducted these tests in a desert location.[27] Air Force commander Hossein Salami advised that Iran was ready to retaliate to military threats, saying "We warn the enemies who intend to threaten us with military exercises and empty psychological operations that our hand will always be on the trigger and our missiles will always be ready to launch".[28]

One day later, on 9 July 2008, Iran once-again fired a version of the Shahab-3, amongst other missiles, which officials have said has a range of 1,250 miles (2,010 km) and is armed with a 1-ton conventional warhead. These tests were conducted at the Strait of Hormuz, which Iran has threatened to shut down traffic into if it is attacked. Independent national security webblog, ArmsControlWonk.com, analyzed Iranian launch footage and concluded that Iranian claims of testing an upgraded Shahab missile were unfounded.[29] A senior Republican Guard commander said Iran would maintain security in the Strait of Hormuz and the Persian Gulf. Gen. Mohammad Hejazi, chief of the Guards' joint staff, called the missile tests a "defensive measure against invasions". He also said, Iran will not jeopardize the interests of neighboring countries. According to the Israeli newspaper Haaretz, the French news agency Agence France-Presse which published pictures from the missile test reported that "Iran had apparently doctored photographs of missile test-firings and exaggerated the capabilities of the weapons" and that an additional missile was added afterwards to cover up a failed launch".[30]

In a sign of commercial fallout from the second missile test in two days, the French oil company Total S.A. announced the conditions were not right to invest in Iran as major oil companies have been under increasing political pressure from the United States and its allies over their activities in Iran amid mounting tensions over Iran's nuclear program. To ratchet up the pressure further, Israel also showed off its latest spy plane in what is seen as a display of strength in response to Iranian war games (missile tests).[31]

The test on 8 July 2008 caused anxiety, the tests were seen widely as a response to Israeli aerial war games staged earlier in the month. Ali Shirazi, representative of the Revolutionary Guards naval forces said, warned that Iran would "set fire" to Israel and the U.S. Navy in the Persian Gulf as its first response to any pre-emptive strike by America or Israel over its nuclear program.[32] Brig. Gen. Hoseyn Salami, commander of Iran's Revolutionary Guards' air force, said: "Our missiles are ready for shooting at any place and any time, quickly and with accuracy".[33] He also made the statement that "enemy targets are under surveillance".[34] Speaking on a visit to Malaysia on the first day of the tests, Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad dismissed the possibility of an attack by the United States or Israel as a "joke".[33]

General Mohammad Hejazi, chief of the Guards' joint staff, called the missile tests a "defensive measure against invasions". He also said that Iran will not jeopardize the interests of neighboring countries.

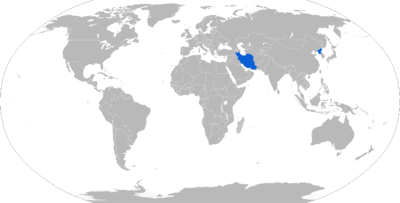

Operators

Current operators

See also

- Military of Iran

- Iranian military industry

- Equipment of the Iranian Army

References

- https://missilethreat.csis.org/missile/shahab-3/

- Shahab-3 / Zelzal-3 fas.org

- https://missilethreat.csis.org/missile/shahab-3/

- https://www.nasic.af.mil/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=F2VLcKSmCTE%3d&portalid=19

- http://www.jcpa.org/brief/brief005-26.htm

- Toukan, Abdullah; Anthony H. Cordesman. "GCC – Iran: Operational Analysis of Air, SAM and TBM Forces" (pdf). Center for Strategic & International Studies. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- Wright, David C.; Timur Kadyshev (1994). "An Analysis of the North Korean Nadong Missile" (pdf). Science & Global Security. Gordon and Breach Science Publishers S.A. 4 (2): 129–160. doi:10.1080/08929889408426397. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- https://missilethreat.csis.org/missile/shahab-3/

- U.S. Department of Defense (2001). Proliferation: Threat and Response (PDF). DIANE Publishing. p. 38. ISBN 1-4289-8085-7.

- The North-Korean/Iranian Nodong-Shahab missile family b14643.de

- Federation of American Scientists. Shahab-3 / Zelzal-3 fas.org

- https://missilethreat.csis.org/missile/shahab-3/

- "Iranian President Defies West At Military Parade". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 22 September 2007. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- "Iran Shows Home-Made Warfare Equipment at Military Parade". Fars News Agency. 22 September 2007. Archived from the original on 2014-02-27. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- "Ghadr-1". Missile Threat. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- Gertz, William (1997-05-22). "Russia disregards pledge to curb Iranian missile output; Tehran, Moscow sign pacts for additional support". The Washington Times.

- Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat (Report). Defense Intelligence Ballistic Missile Analysis Committee. June 2017. p. 25. NASIC-1031-0985-17. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- "Shahab 3: an Advanced IRBM". acig.org. Archived from the original on 2008-06-15. Retrieved 2008-07-12.

- Cordesman, A.H. (2005). National Security in Saudi Arabia: Threats, Responses and Challenges. Center for Strategic and International Studies. pp. 30. ISBN 0-275-98811-2.

- "Report: Iran manufacturing improved missile". Ynetnews. Yedioth Ahronoth. 11 December 2008. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- "Iran confirms test of missile that is able to hit Israel". New York Times. 2003-07-08. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- "Iran begins serial production of Shahab-3". Janes Defence Weekly. Archived from the original on August 4, 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- "Iran fires unarmed missiles". CNN. Reuters. 2 November 2006. Archived from the original on 2 November 2006. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- Cowell, Alan (2008-07-09). "Iran tests missiles amid tension over nuclear program". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

- Gordon, Michael R.; Schmitt, Eric (2008-06-20). "U.S. says exercise by Israel seemed directed at Iran". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

- "Iran test-fires upgraded Shahab-3 missile". Payvand. 2008-07-09. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- "Iran test-fires Shahab-3 long-range missile". Thaindian News. RIA Novosti. 2008-07-09. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- Peterson, Scott (10 July 2008). "Confrontation escalates between Iran and Israel". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- Hess, Pamela (12 July 2008). "Official: Iran missile tests used 'old equipment'". The AP. Archived from the original on 15 July 2008. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- "Did Iran doctor an image of its missile test launch?". Haaretz. Agence France-Presse. 2008-07-11. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- Karimi, Nasser (10 July 2008). "Iran test-fires more missiles in Persian Gulf". USA Today. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- Williams, Stuart (9 July 2008). "Defiant Iran angers US with missile test". France 24. Archived from the original on 12 February 2009. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- "Iran missile test 'provocative'". BBC News. 2008-07-09. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- Pessin, Al (9 July 2008). "US Says Iran's Missile Tests Do Not Make Conflict More Likely". Voice of America. Archived from the original on 10 July 2008. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shahab-3. |

- Shahab-3: an Advanced IRBM

- Encyclopedia Astronautica

- Iranian Missiles, from Sarbaz.org, website of former Iranian Imperial Army loyalists

- Missile Threat CSIS - Shahab 3

- Missile Threat CSIS - Shahab 3 Variants (Emad, Ghadr)

- Shahab-3 MRBM from Military Periscope (login required)

- Russia and the Development of the Iranian Missile Program

- (in Czech) Írán - Námořní cvičení—visual comparison of Shahab-3B and Fajr-3

- Janes Defence Weekly Volume 43 and Issue 37 Iran's ballistic missile developments - long-range ambitions