Mirza Ghiyas Beg

Mirza Ghiyas Beg (Urdu: مرزا غياث بيگ), also known by his title of I'timad-ud-Daulah (Persian: اعتمادالسلطنه آگهی الدوله), was an important Persian official in the Mughal empire, whose children served as wives, mothers, and generals of the Mughal emperors.

Mirza Ghiyas | |

|---|---|

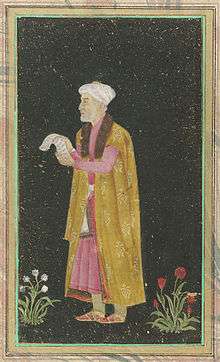

An 18th-century portrait of Mirza Ghiyas Beg. Color and gold over gold-sprinkled black ground on paper. | |

| Vakil of the Mughal Empire (Grand Vizier) | |

| In office 1611–1622 | |

| Monarch | Jahangir |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Mid 16th-century Tehran, Safavid Iran |

| Died | 1622 near Kangra, Mughal India |

| Spouse(s) | Asmat Begam |

| Relations | Khvajeh Mohammad-Sharif (father) Mohammad-Taher Wasli (brother) Jahangir (son-in-law) |

| Children | Muhammad-Sharif Ibrahim Khan Fath Jang Itiqad Khan Abu'l-Hasan Asaf Khan Nur Jahan Manija Begum[1] Sahlia Begum |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Mughal Empire |

| Years of service | 1577–1622 |

Born in Tehran, Ghiyas Beg belonged to a family of poets and high officials. Nevertheless, his fortunes fell into disfavor after the death of his father in 1576. Along with his pregnant wife Asmat Begum, and his three children, they immigrated to India. There he was received by the Mughal emperor Akbar (r. 1556-1605), and was enrolled into his service. During the latters reign, Ghiyas Beg was appointed treasurer for the province of Kabul.

His fortunes further increased during the reign of Akbar's son and successor Jahangir (r. 1605-1627), who in 1611 married his daughter Nur Jahan and appointed Ghiyas Beg as his Prime minister. By 1615, Ghiyas Beg had risen to further prominence, when he was given the status of 6,000 men and was given a standard and drums, a prestige normally restricted for distinguished princes.

Family

Ghiyas Beg was a native of Tehran, and was the youngest son of Khvajeh Mohammad-Sharif, a poet and vizier of Mohammad Khan Tekkelu and his son Tatar Soltan, who was the governor of the Safavid province of Khorasan. Mohammad-Sharif was later listed under the service of Shah Tahmasp I (r. 1524–1576), where he in the start served as the vizier of Yazd, Abarkuh, and Biabanak for seven years. Thereafter he was appointed as the vizier of Isfahan, and died there in 1576.[2] Ghiyas Beg's elder brother, Mohammad-Taher Wasli, was a learned man who composed poetry under the pen name of Wasli.[3]

Immigration to India

After the death of Ghiyas' father, his family fell into disgrace. Hoping to improve his family’s fortunes, Ghiyas Beg chose to relocate to India where the Emperor Akbar's court was said to be at the centre of the growing trade industry and cultural scene.[4] Half way along their route the family was attacked by robbers who took from them the remaining meager possessions they had.[5]

Left with only two mules, Ghiyas Beg, his pregnant wife, and their three children (Mohammad-Sharif, Asaf Khan and a daughter Sahlia) were forced to take turns riding on the backs of the animals for the rest of their journey. When the family arrived in Kandahar, Asmat Begam gave birth to their second daughter. The family was so impoverished, they feared they would be unable to take care of the newborn baby. Fortunately, the family was taken in by a caravan led by the merchant noble Malik Masud, who would later assist Ghiyas Beg in finding a job in the service of Emperor Akbar. Believing that the child had signaled a change in the family’s fate, she was named Mehrunnisa, meaning "sun among women".[6] Ghiyas Beg was not the first member of his family to move to India—his cousin Asaf Khan Jafar Beg and the uncle of Asmat Begum, Mirza Ghiyasuddin Ali Asaf Khan, had been enrolled into the provincial assignments of Akbar.[7]

Service under the Mughal Empire

Ghiyas was later appointed diwan (treasurer) for the province of Kabul. Due to his astute skills at conducting business he quickly rose through the ranks of the high administrative officials. For his excellent work he was awarded the title of ‘‘Itimad-ud-Daula‘‘ (‘Pillar of the State’) by the emperor.[5] As a result of his work and promotions, Ghiyas Beg was able to ensure that Mehrunnisa (the future Nur Jahan) would have the best possible education. She became well versed in Arabic and Persian. She also became well versed in art, literature, music and dance.[6]

Ghiyas' daughter, Mehrunissa (Nur Jahan) married Akbar's son Jahangir in 1611, and his son Abdul Hasan Asaf Khan served as a general to Jahangir.

Ghiyas was also the grandfather of Mumtaz Mahal (originally named Arjumand Bano, daughter of Abdul Hasan Asaf Khan), the wife of the emperor Shah Jahan, responsible for the building of the Taj Mahal. Jahangir was succeeded by his son Shah Jahan, and Abdul Hasan served as one of Shah Jahan's closest advisors. Shah Jahan married Abdul Hasan's daughter Arjumand Banu Begum, Mumtāz Mahal, who was the mother of his four sons, including his successor Aurangzeb. Shah Jahan built the Taj Mahal to serve as Mumtaz Mahal's tomb.

Death and burial

Ghiyas Beg died near Kangra in 1622 while the Mughal camp was moving towards its summer residence in Kashmir. His body was carried back to Agra, where he was buried on the right bank of the Yamuna river. His burial place still stands till this day, and is known as Tomb of I'timad-ud-Daulah.

References

- Koch, Ebba; Losty, JP. "The Riverside Mansions and Tombs of Agra: New Evidence from a Panoramic Scroll Recently Acquired by The British Library" (PDF).

- Shokoohy 2001, pp. 594–595.

- Banks Findley 1993, p. 9.

- Gold 2008, p. 148

- Chandra 1978, p. 4

- Nath 1990, p. 66

- Banks Findley 1993, p. 8.

Sources

- Shokoohy, Mehrdad (2001). "GĪĀṮ BEG, ʿEʿTEMĀD-AL-DAWLA". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. X, Fasc. 6. pp. 594–595.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nath, Renuka (1990). Notable Mughal and Hindu women in the 16th and 17th centuries A.D. New Delhi: Inter-India Publ. ISBN 9788121002417.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gold, Claudia (2008). Queen, Empress, Concubine: Fifty Women Rulers from Cleopatra to Catherine the Great. London: Quercus. ISBN 978-1-84724-542-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Banks Findley, Ellison (11 Feb 1993). Nur Jahan: Empress of Mughal India. Oxford, UK: Nur Jahan : Empress of Mughal India. ISBN 9780195074888.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Keay, John (2000). India: A History. Grove Press, New York.