Seven Days in May

Seven Days in May is a 1964 American political thriller film about a military-political cabal's planned takeover of the United States government in reaction to the president's negotiation of a disarmament treaty with the Soviet Union. The picture was directed by John Frankenheimer; starring Burt Lancaster, Kirk Douglas, Fredric March, and Ava Gardner; with the screenplay written by Rod Serling based on the novel of the same name by Fletcher Knebel and Charles W. Bailey II, published in September 1962.[2]

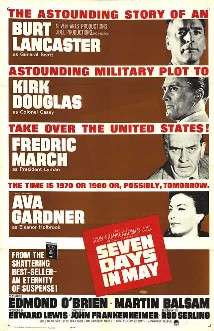

| Seven Days in May | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Frankenheimer |

| Produced by | Edward Lewis |

| Screenplay by | Rod Serling |

| Based on | Seven Days in May by Fletcher Knebel & Charles W. Bailey II |

| Starring | Burt Lancaster Kirk Douglas Fredric March Ava Gardner |

| Music by | Jerry Goldsmith |

| Cinematography | Ellsworth Fredricks |

| Edited by | Ferris Webster |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 118 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2.2 million |

| Box office | $3,650,000 (rentals)[1] |

Background

The book was written in late 1961 and into early 1962, during the first year of the Kennedy administration, reflecting some of the events of that era. In November 1961, President John F. Kennedy accepted the resignation of vociferously anti-Communist General Edwin Walker who was indoctrinating the troops under his command with personal political opinions and had described former President Harry S. Truman, former United States Secretary of State Dean Acheson, former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and other recent still-active public figures as Communist sympathizers.[3] Although no longer in uniform, Walker continued to be in the news as he ran for Governor of Texas and made speeches promoting strongly right-wing views. In the film version of Seven Days in May, Fredric March, portraying the narrative's fictional President Jordan Lyman, mentions General Walker as one of the "false prophets" who were offering themselves to the public as leaders. (John F. Kennedy assassin Lee Harvey Oswald purportedly fired rifle shots into the home of General Walker in April 1963.)[4]

As they collaborated on the novel, Knebel and Bailey, who were primarily political journalists and columnists, also conducted interviews with another controversial military commander, the newly appointed Air Force Chief of Staff, General Curtis LeMay, who was angry with Kennedy for refusing to provide air support for the Cuban rebels in the Bay of Pigs Invasion.[5][6] The character of General James Mattoon Scott itself was believed to be inspired by both General Curtis LeMay and General Edwin Walker.

President Kennedy had read Seven Days in May shortly after its publication and believed the scenario as described could actually occur in the United States. According to Frankenheimer in his director's commentary, production of the film received encouragement and assistance from Kennedy through White House Press Secretary Pierre Salinger, who conveyed to Frankenheimer Kennedy's wish that the film be produced and that, although the Pentagon did not want the film made, the President would arrange to be visiting Hyannis Port for a weekend when the film needed to shoot outside the White House.[7]

Plot

The story is set in 1974, ten years in the future at the time of the film's 1964 release, and the Cold War is still a problem (in the 1962 book, the setting was May 1974 after a stalemated war in Iran). U.S. President Jordan Lyman has recently signed a nuclear disarmament treaty with the Soviet Union, and the subsequent ratification by the U.S. Senate has produced a wave of dissatisfaction, especially among Lyman's opposition and the military, who believe the Soviets cannot be trusted.

A Pentagon insider, United States Marine Corps Colonel "Jiggs" Casey (the Director of the Joint Staff), stumbles on evidence that the Joint Chiefs of Staff, led by its charismatic chairman United States Air Force General James Mattoon Scott who was a former fighter pilot, a war veteran, a flying ace, Medal of Honor recipient and an honorable patriot, intend to stage a coup d'etat to remove Lyman and his cabinet in seven days. Under the plan, a secret Army unit known as ECOMCON (Emergency COMmunications CONtrol) will seize control of the country's telephone, radio, and television networks, while Congress is prevented from implementing the treaty. Although personally opposed to Lyman's policies, Casey is appalled by the plot and alerts Lyman, who gathers a circle of trusted advisors to investigate: Secret Service White House Detail Chief Art Corwin, Treasury Secretary Christopher Todd, advisor Paul Girard, and Senator Raymond Clark of Georgia.

Casey uses the pretense of a social visit to General Scott's former mistress to ferret out potential secrets that can be used against Scott, in the form of indiscreet letters he had written her. Meanwhile, the alcoholic Clark is sent to Fort Bliss near El Paso, Texas, to locate the secret base, and Girard leaves for the Mediterranean to obtain a confession from Vice Admiral Barnswell, who declined to participate in the coup. Girard gets the confession in writing, but is killed when his return flight crashes, while Clark is taken captive when he reaches the secret base. However, Clark convinces the base's deputy commander, Colonel Henderson, a friend of Casey's, not to be a party to the coup and to help him escape. They reach Washington, DC, but Henderson is abducted during a moment apart from Clark and confined in a military stockade.

Lyman calls Scott to the White House to demand that he and the other plotters resign. Scott denies the existence of the plot, but takes the opportunity to denounce Lyman and the treaty. Lyman argues that a coup in America would prompt the Soviets to make a preemptive strike. Scott maintains that the American people are behind him. Lyman is on the verge of confronting Scott with the letters obtained from Scott's mistress when he decides against it and allows Scott to leave.

Scott meets the other three Joint Chiefs, demanding they stay in line and reminding them that Lyman does not seem to have concrete evidence of their plot. Somewhat reassured, the others agree to continue the plan to appear on television and radio simultaneously on the next day to denounce Lyman. However, Lyman first holds a press conference, at which he is prepared to announce that he has fired the four men. As Lyman is speaking, Barnswell's hand-written confession, recovered from the plane crash, is handed to him and he delays the conference for half an hour. In the interim, copies of the confession are delivered to Scott and the other plotters. As the broadcast of the press conference resumes, Scott prepares to go forward with the coup anyway, but then gives up when he hears President Lyman announce that the other three plotters have tendered their resignations. The film ends with an address by Lyman to American people on the country's future, and leaves unanswered the question of General Scott's fate.

Cast

|

|

Unbilled speaking roles (in order of appearance)

- Malcolm Atterbury (Horace, president's physician: "Why, in God's name, do we elect a man president and then try to see how fast we can kill him?")

- Jack Mullaney ("All properly decoded in four point oh fashion and respectfully submitted by yours truly, Lieutenant junior grade, Dorsey Grayson.")

- Charles Watts (Stu Dillard, Washington insider: "Oh, Senator, pardon me, come along, I want you to meet the wife of the Indian ambassador.")

- John Larkin (Colonel John Broderick, one of the conspirators: "Well, well, well, if it isn't my favorite jarhead himself, Jiggs Casey.")

- Colette Jackson (Girl speaking to Senator Clark in Charlie's Bar, near secret base in Texas: "You wonder what the country's comin' to. All those boys sittin' up in the desert never seein' no girls. Why, they might as well be in stir.")

- John Houseman (Vice Admiral Farley C. Barnswell, declined conspirator: "I'm sorry, sir. I can only recount to you the situation as it occurred. I signed no paper. He took nothing with him.")

- Rodolfo Hoyos Jr. (Captain Ortega, commander at airplane crash site in Spain: "There were only two American nationals on board — a Mrs. Agnes Buchanan from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and a Mister Paul Girard. His destination was Washington.")

- Fredd Wayne (Henry Whitney, official from the American embassy in Spain: "You find any effects of the Americans? Anything at all?")

- Tyler McVey (General Hardesty, NORAD commander: "Barney Rutkowski, Air Defense. He's screaming bloody murder about those twelve troop carriers dispatched to El Paso.")

- Ferris Webster [editor of Seven Days in May] (General Barney Rutkowski: "There's some kind of a secret base out there, Mr. President, and I think I should have been notified of it.")

Character names

Other than the billing, "Also starring Ava Gardner as Eleanor Holbrook" (Scott's mistress), none of the other characters is identified by name in the credits, thus although Kirk Douglas' "Jiggs Casey" and Andrew Duggan's "Mutt Henderson" are described in the book as having the given names of "Martin" and "William", respectively, those names are never mentioned in the film. Also, while Rod Serling's screenplay names the head of the White House Secret Service as "Art Corwin", in the film he is only referred to as "Art" or "Arthur". The surname "Corwin" was a tribute to the radio drama writer Serling described as his idol, Norman Corwin,[8] while the given name "Art" was a nod to Serling's personal favorite, Art Carney, who played a fictionalized version of Serling in Serling's autobiographical 1959 Playhouse 90 drama, "The Velvet Alley", as well as the reincarnated Santa Claus, "Henry Corwin", in "The Night of the Meek", Serling's 1960 Christmas episode of The Twilight Zone.

Cast members whose participation has been noted in various sources

- At the 35th Academy Awards on April 8, 1963, while Seven Days in May was still in its pre-production and casting stages, What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?'s Victor Buono was one of the four unsuccessful nominees vying for Best Supporting Actor. His name appears on a list of actors engaged for the production, but there is no confirmation of his actual participation in the filming.

- On September 17, 1963, as Seven Days in May was in initial production days, ABC showcased the premiere episode of its new TV series, The Fugitive, which prominently featured one-armed bit player Bill Raisch in the iconic, non-speaking, intermittent role of the killer. He is also listed among those who were scheduled to play a part in the filming, but whether he ultimately did has not been confirmed. Raisch was previously used by Kirk Douglas for a notorious scene in his 1960 film epic Spartacus in which, playing a Roman soldier, Raisch had a specially-fitted prosthetic arm chopped off in battle. Douglas engaged him again for a dramatic fight scene in his 1962 modern-day western Lonely Are the Brave.

- Although he cannot be discerned in the release version of Seven Days in May, minor supporting actor Leonard Nimoy, who gained stardom three years later, in 1966, as Star Trek's Mr. Spock, likewise appears in the production company's casting list among the unbilled actors whose services were retained for this film.[9]

Production

Kirk Douglas and director John Frankenheimer were the moving forces behind the filming of Seven Days in May; the film was produced by Edward Lewis through Douglas's company Joel Productions and Seven Arts Productions. Frankenheimer wanted the screenwriter to be a partner in the production, and Rod Serling agreed to this arrangement. Douglas agreed to star in it, but he also wanted his frequent co-star Burt Lancaster to star in the film as well. Douglas enticed Lancaster to join the film by offering him the meatier role of General Scott, the film's villain, while Douglas agreed to take the role of Scott's assistant.[10] Lancaster's involvement almost caused Frankenheimer to back out, since he and Lancaster had butted heads on Birdman of Alcatraz two years earlier. Only Douglas's assurances that Lancaster would behave kept the director on the project.[11] Ironically, Lancaster and Frankenheimer got along well during the filming, while Douglas and the director had a falling-out.[12][13] Frankenheimer was also very happy with Lancaster's performance, and noted in the long scene toward the end between Lancaster and March, probably his all-time favourite directed scene, that Lancaster was "perfect" in his delivery and that no other actor could have done it better.[14] Most of the actors in the film Frankenheimer had worked with previously, a directorial preference. Frankenheimer, in the DVD commentary for the film, stated that he would not have made the movie any differently decades later and that it was one of the films he was most satisfied with.[14] He saw it as a chance to "put a nail in the coffin of McCarthy".[14]

Many of Lancaster's scenes were shot later on as he was recovering from hepatitis.[14] The filming took 51 days and according to the director the production was a happy affair, and all of the actors and crew displayed great reverence for Fredric March.[14] Ava Gardner, whose scenes were shot in just six days, however, thought that Frankenheimer favored the other actors over her and Martin Balsam objected to his habit of shooting off pistols behind him during important scenes.[11] Frankenheimer remarked that she was a "lovely person" and overwhelmingly beautiful, but at times "difficult" to work with.[14] The director had formerly been in the military and had been inside the Pentagon so he didn't have to conduct much research for the film; he stated that the sets were totally authentic, praising the production designer.[14] In addition, many of the scenes in the film were loosely based on real-life events of the Cold War to provide authenticity.[15]

In an early example of guerrilla filmmaking, Frankenheimer photographed Martin Balsam being ferried out to the supercarrier USS Kitty Hawk, berthed at Naval Air Station North Island in San Diego (standing in for Gibraltar), without prior Defense Department permission. Frankenheimer needed a commanding figure to play Vice Admiral Farley C. Barnswell and asked his friend, well-known producer John Houseman, to play him, to which he agreed, on condition that he have a fine bottle of wine (which is seen during the telephone scene), although he was uncredited for the role. It was Houseman's American acting debut, and he would not appear onscreen again until his Oscar-winning role in The Paper Chase (1973). Frankenheimer also wanted a shot of Kirk Douglas entering the Pentagon, but could not get permission because of security considerations, so he rigged a movie camera in a parked station wagon to photograph Douglas walking up to the Pentagon. Douglas actually received salutes from military personnel inasmuch as he was wearing the uniform of a U.S. Marine Corps colonel.[16] Several scenes, including one with nuns in the background, were shot inside Washington Dulles International Airport which had recently been built, and the production team were the first ever to film there.[14] The alley and car park scene was shot in Hollywood, and other footage was shot in the Californian desert in 110 degree heat. The secret base and airstrip was specially built in the desert near Indio, California, and they borrowed an aircraft tail in one shot to make it look like a whole plane was off the picture.[14] Originally the script had Lancaster die in a car crash at the end after hitting a bus, but finally this was edited out in favor of a small scene of him departing by taxi which was shot on a Sunday in Paris during production of The Train (1964).[14]

Getting permission near the White House was easier. Frankenheimer said that Pierre Salinger conveyed to him President Kennedy's wish that the film be made; "these were the days of General Walker" and, though the Pentagon did not want the film made, the president would conveniently arrange to visit Hyannis Port for a weekend when the film needed to shoot a staged riot outside the White House.[17] Kirk Douglas recalled President Kennedy approving of the making of the film.[18] The director considered the scene in which Douglas's character visits the president to be a masterful scene of acting which would have been technically very difficult for most actors to sustain.[14] He had done similar scenes on many television shows, and every camera angle and shot was extensively planned and rehearsed as was the acting in the scene by the actors. Frankenheimer paid particular attention to ensuring that the three actors in the scene were all in focus for dramatic impact. Many of Frankenheimer's signature shots were used in scenes such as this throughout the film, including his "depth of focus" shot with one or two people near the camera and another or others in the distance and the "low angle, wide-angle lens" (set at f/11) which he considered to give "tremendous impact" on a scene.[14]

Some efforts were made in the film to have the movie appear to take place in the near future, for instance the use of the then-futuristic technology of video teleconferencing, and of the use of (more exotic) foreign cars in place of (more ordinary) American cars. The film also featured the then recently issued M16 rifle.

David Amram, who had previously scored Frankenheimer's The Manchurian Candidate (1962), originally provided music for the film; however Lewis was unsatisfied with his work. Jerry Goldsmith, who had worked with the producer and Douglas on Lonely are the Brave (also 1962) and The List of Adrian Messenger (1963), was signed to rescore the project (although a brief source cue by Amram remains in the finished film). Goldsmith composed a very brief score (lasting around 15 minutes) using only pianos and percussion; he later scored Seconds (1966) and The Challenge (1982) for Frankenheimer.[19] In 2013, Intrada Records released Goldsmith's music for the film on a limited edition CD (paired with Maurice Jarre's score for The Mackintosh Man - although that film was produced by Warner Bros. while Seven Days in May was theatrically released by Paramount, the entire Seven Arts Productions library was acquired by Warner Bros. in 1967 (meaning both films are now owned by WB).

Alternate ending

According to Douglas, an alternate ending was shot, but discarded:

General Scott, the treacherous Burt Lancaster character, goes off in his sports car, and dies in a wreck. Was it an accident or suicide? Coming up out of the wreckage over the car radio is President Jordan Lyman's speech about the sanctity of the Constitution.[13]

This alternate ending echoes the novel, which ends with the apparent vehicular suicide of Senator Prentice.

Reception

Seven Days in May premiered on February 12, 1964, appropriately in Washington, D.C.[20] It opened to good critical notices and audience response.[11]

The film was nominated for two 1965 Academy Awards,[21] for Edmond O'Brien for Best Actor in a Supporting Role, and for Best Art Direction-Set Decoration/Black-and-White for Cary Odell and Edward G. Boyle. In that year's Golden Globe Awards, O'Brien won for Best Supporting Actor, and Fredric March, John Frankenheimer and composer Jerry Goldsmith received nominations.

Frankenheimer won a Danish Bodil Award for directing the Best Non-European Film and Rod Serling was nominated for a Writers Guild of America Award for Best Written American Drama.

Evaluation in film guides

Steven H. Scheuer's Movies on TV (1972–73 edition) gives Seven Days in May its highest rating of 4 stars, recommending it as "an exciting suspense drama concerned with politics and the problems of sanity and survival in a nuclear age", with the concluding sentences stating, "benefits from taut screenplay by Rod Serling and the direction of John Frankenheimer, which artfully builds interest leading to the finale. March is a standout in a uniformly fine cast. So many American-made films dealing with political subjects are so naive and simple-minded that the thoughtful and, in this case, the optimistic statement of the film is a welcome surprise." By the 1986–87 edition, Scheuer's rating was lowered to 3½ and the conclusion shortened to, "which artfully builds to the finale", with the final sentences deleted. Leonard Maltin's TV Movies & Video Guide (1989 edition) gives it a still lower 3 stars (out of 4), originally describing it as an "absorbing story of military scheme to overthrow the government", with later editions (including 2014) adding one word, "absorbing, believable story..."

Videohound's Golden Movie Retriever follows Scheuer's later example, with 3½ bones (out of 4), calling it a "topical but still gripping Cold War nuclear-peril thriller" and, in the end, "highly suspenseful, with a breathtaking climax." Mick Martin's & Marsha Porter's DVD & Video Guide also puts its rating high, at 4 stars (out of 5) finding it, as Videohound did, "a highly suspenseful account of an attempted military takeover..." and indicating that "the movie's tension snowballs toward a thrilling conclusion. This is one of those rare films that treat their audiences with respect." Assigning the equally high rating of 4 stars (out of 5), The Motion Picture Guide begins its description with "a taut, gripping, and suspenseful political thriller which sports superb performances from the entire cast", goes to state, in the middle, that "proceeding to unravel its complicated plot at a rapid clip, SEVEN DAYS IN MAY is a surprisingly exciting film that also packs a grim warning", and ends with "Lancaster underplays the part of the slightly crazed general and makes him seem quite rational and persuasive. It is a frightening performance. Douglas is also quite good as the loyal aide who uncovers the fantastic plot that could destroy the entire country. March, Balsam, O'Brien, Bissell, and Houseman all turn in topnotch performances and it is through their conviction that the viewer becomes engrossed in this outlandish tale."

British references also show high regard for the film, with TimeOut Film Guide's founding editor Tom Milne indicating that "conspiracy movies may have become more darkly complex in these post-Watergate days of Pakula and paranoia, but Frankenheimer's fascination with gadgetry (in his compositions, the ubiquitous helicopters, TV screens, hidden cameras and electronic devices literally edge the human characters into insignificance) is used to create a striking visual metaphor for control by the military machine. Highly enjoyable." In his Film Guide, Leslie Halliwell provided 3 stars (out of 4), describing it as an "absorbing political mystery drama marred only by the unnecessary introduction of a female character. Stimulating entertainment." David Shipman in his 1984 The Good Film and Video Guide gives 2 (out of 4) stars, noting that it is "a tense political thriller whose plot is plotting".

Remake

The film was remade in 1994 by HBO as The Enemy Within with Sam Waterston as President William Foster, Jason Robards as General R. Pendleton Lloyd, and Forest Whitaker as Colonel MacKenzie 'Mac' Casey. This version followed many parts of the original plot closely, while updating it for the post–Cold War world, omitting certain incidents, and changing the ending.

See also

- List of American films of 1964

- List of fictional revolutions and coups

- Politics in fiction

- A Very British Coup, a 1988 three-episode serial, based on Chris Mullin's novel about an attempted right-wing overthrow of a left-wing British government

References

Notes

- "Big Rental Pictures of 1964", Variety, p. 39, January 6, 1965.

- "Seven Days in May" (Kirkus Reviews, September 10, 1962)

- "Armed Forces: I Must Be Free..." (Time Magazine, November 10, 1961)

- United States. Warren Commission (1964). Report of the Warren Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy. McGraw-Hill Book Company. pp. 282–.

- Stoddard, Brooke C. "Seven Days in May: Remembrance of Books Past" (Washington Independent Review of Books, November 27, 2012)

- Steed, Mark S. "Seven Days in May by Knebel and Bailey - Book Review" (An Independent Head, October 26, 2013)

- Kakutani, Michiko. Kennedy, and What Might Have Been: 'JFK's Last Hundred Days' by Thurston Clarke, page 95 (The New York Times, August 12, 2013)

- Romano, Carlin, Inquirer book critic. "He Was So Outspoken About TV He Was Called Its Leading Critic in 1961. (The Philadelphia Inquirer, February 2, 1993)"

- Tom. "Missing Cast Members" (The Old Movie House, February 8, 2012) Archived February 4, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- http://www.tcm.com/this-month/article/160820%7C0/Seven-Days-in-May.html

- Stafford, Jeff, Seven Days in May (article), TCM.

- Frankenheimer, John and Champlin, Charles. John Frankenheimer : A Conversation Riverwood Press, 1995. ISBN 978-1-880756-13-3

- Douglas, Kirk. The Ragman's Son. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1988.

- Frankenheimer, John, Seven Days in May DVD Commentary, Warner Home Video, May 16, 2000

- Antulov, Dragan. "All-Reviews.com Movie/Video Review Seven Days In May" (All-Reviews, 2002)

- Pratley, Gerald. The Cinema of John Frankenheimer London: A. Zwemmer, 1969. ISBN 978-0-302-02000-5.

- Arthur Meier Schlesinger (1978). Robert Kennedy and His Times. ISBN 978-0-7088-1633-2.

- Seven Days in May commentary as part of the Kirk Douglas Featured Collection at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research Archived June 10, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Scott Bettencourt, liner notes, soundtrack album, Intrada Special Collection Vol. 235

- Overview, TCM.

- "Seven Days in May". The New York Times. Retrieved December 25, 2008.

Further reading

- Bamford, James (2001). "Chapter 4: Fists". Body of Secrets: Anatomy of the Ultra-Secret National Security Agency: From the Cold War Through the Dawn of a New Century. New York: Doubleday. pp. 80–91. ISBN 978-0-385-49907-1. OCLC 44713235. Covers an actual plot during the Kennedy administration and within the Joint Chiefs of Staff to start a war.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Seven Days in May |

- Seven Days in May on IMDb

- Seven Days in May at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Seven Days in May at the TCM Movie Database

- Seven Days in May at AllMovie

- Seven Days in May at Rotten Tomatoes

- Seven Days in May at TV Guide (revised form of this 1987 write-up was originally published in The Motion Picture Guide)