Movie camera

The movie camera, film camera or cine-camera is a type of photographic camera which takes a rapid sequence of photographs on an image sensor or on a film. In contrast to a still camera, which captures a single snapshot at a time, the movie camera takes a series of images; each image constitutes a "frame". This is accomplished through an intermittent mechanism. The frames are later played back in a movie projector at a specific speed, called the frame rate (number of frames per second). While viewing at a particular frame rate, a person's eyes and brain merge the separate pictures to create the illusion of motion.[1]

Since the 2000s, digital movie cameras began to exceed the use of film-based movie cameras.

History

An interesting forerunner to the movie camera was the machine invented by Francis Ronalds at the Kew Observatory in 1845. A photosensitive surface was drawn slowly past the aperture diaphragm of the camera by a clockwork mechanism to enable continuous recording over a 12- or 24-hour period. Ronalds applied his cameras to trace the ongoing variations of scientific instruments and they were used in observatories around the world for over a century.[2][3][4]

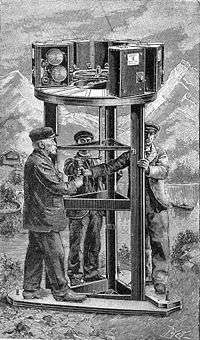

The chronophotographic gun was invented in 1882 by Étienne-Jules Marey, a french scientist and chronophotograph. It could shoot 12 images per second and it was the first invention to capture moving images on the same chronomatographic plate using a metal shutter.[5]

In 1876, Wordsworth Donisthorpe proposed a camera to take a series of pictures on glass plates, to be printed on a roll of paper film. In 1889, he would patent a moving picture camera in which the film moved continuously. Another film camera was designed in England by Frenchman Louis Le Prince in 1888. He had built a 16 lens camera in 1887 at his workshop in Leeds. The first 8 lenses would be triggered in rapid succession by an electromagnetic shutter on the sensitive film; the film would then be moved forward allowing the other 8 lenses to operate on the film. After much trial and error, he was finally able to develop a single-lens camera in 1888, which he used to shoot sequences of moving pictures on paper film, including the Roundhay Garden Scene and Leeds Bridge.

Another early pioneer was the British inventor William Friese-Greene. In 1887, he began to experiment with the use of paper film, made transparent through oiling, to record motion pictures. He also said he attempted using experimental celluloid, made with the help of Alexander Parkes. In 1889, Friese-Greene took out a patent for a moving picture camera that was capable of taking up to ten photographs per second. Another model, built-in 1890, used rolls of the new Eastman celluloid film, which he had perforated. A full report on the patented camera was published in the British Photographic News on February 28, 1890.[6] He showed his cameras and film shot with them on many occasions, but never projected his films in public. He also sent details of his invention to Edison in February 1890[7], which was also seen by Dickson (see below).

William Kennedy Laurie Dickson, a Scottish inventor and employee of Thomas Edison, designed the Kinetograph Camera in 1891. The camera was powered by an electric motor and was capable of shooting with the new sprocketed film. To govern the intermittent movement of the film in the camera, allowing the strip to stop long enough so each frame could be fully exposed and then advancing it quickly (in about 1/460 of a second) to the next frame, the sprocket wheel that engaged the strip was driven by an escapement disc mechanism—the first practical system for the high-speed stop-and-go film movement that would be the foundation for the next century of cinematography.[8]

The Lumière Domitor camera, owned by brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière, was created by Charles Moisson, the chief mechanic at the Lumière works in Lyon in 1894. The camera used paper film 35 millimeters wide, but in 1895, the Lumière brothers shifted to celluloid film, which they bought from New-York’s Celluloid Manufacturing Co. This they covered with their own Etiquette-bleue emulsion, had it cut into strips and perforated.

In 1894, the Polish inventor Kazimierz Prószyński constructed a projector and camera in one, an invention he called the Pleograph.[9][10][11][12][13]

Mass-market

Due to the work of Le Prince, Friese-Greene, Edison, and the Lumière brothers, the movie camera had become a practical reality by the mid-1890s. The first firms were soon established for the manufacture of movie camera, including Birt Acres, Eugene Augustin Lauste, Dickson, Pathé frères, Prestwich, Newman & Guardia, de Bedts, Gaumont-Démény, Schneider, Schimpf, Akeley, Debrie, Bell & Howell, Leonard-Mitchell, Ertel, Ernemann, Eclair, Stachow, Universal, Institute, Wall, Lytax, and many others.

The Aeroscope was built and patented in England in the period 1909–1911 by Polish inventor Kazimierz Prószyński.[14] Aeroscope was the first successful hand-held operated film camera. The cameraman did not have to turn the crank to advance the film, as in all cameras of that time, so he could operate the camera with both hands, holding the camera and controlling the focus. This made it possible to film with the Aeroscope in difficult circumstances including from the air and for military purposes.[15]

The first all-metal cine camera was the Bell & Howell Standard of 1911-12. One of the most complicated models was the Mitchell-Technicolor Beam Splitting Three-Strip Camera of 1932. With it, three colour separation originals are obtained behind a purple, a green, and a red light filter, the latter being part of one of the three different raw materials in use.

In 1923, Eastman Kodak introduced a 16mm film stock, principally as a lower-cost alternative to 35 mm and several camera makers launched models to take advantage of the new market of amateur movie-makers. Thought initially to be of inferior quality to 35 mm, 16 mm cameras continued to be manufactured until the 2000s by the likes of Bolex, Arri, and Aaton.

Digital movie cameras

Digital movie cameras do not use analog film stock to capture images, as had been the standard since the 1890s. Rather, an electronic image sensor is employed and the images are typically recorded on hard drives or flash memory—using a variety of acquisition formats. Digital SLR cameras (DSLR) designed for consumer use have also been used for some low-budget independent productions.

Since the 2010s, digital movie cameras have become the dominant type of camera in the motion picture industry, being employed in film, television productions and even (to a lesser extent) video games. In response to this, movie director Martin Scorsese started the non-profit organisation The Film Foundation to preserve the use of film in movie making—as many filmmakers feel DSLR cameras do not convey the depth or emotion that motion-picture film does. Other major directors involved in the organisation include Quentin Tarantino, Christopher Nolan and many more.[16]

Technical details

Most of the optical and mechanical elements of a movie camera are also present in the movie projector. The requirements for film tensioning, take-up, intermittent motion, loops, and rack positioning are almost identical. The camera will not have an illumination source and will maintain its film stock in a light-tight enclosure. A camera will also have exposure control via an iris aperture located on the lens. The righthand side of the camera is often referred to by camera assistants as "the dumb side" because it usually lacks indicators or readouts and access to the film threading, as well as lens markings on many lens models. Later equipment often had done much to minimize these shortcomings, although access to the film movement block by both sides is precluded by basic motor and electronic design necessities. Advent of digital cameras reduced the above mechanism to a minimum removing much of the shortcomings.

The standardized frame rate for commercial sound film is 24 frames per second. The standard commercial (i.e., movie-theater film) width is 35 millimeters, while many other film formats exist. The standard aspect ratios are 1.66, 1.85, and 2.39 (anamorphic). NTSC video (common in North America and Japan) plays at 29.97 frame/s; PAL (common in most other countries) plays at 25 frames. These two television and video systems also have different resolutions and color encodings. Many of the technical difficulties involving film and video concern translation between the different formats. Video aspect ratios are 4:3 (1.33) for full screen and 16:9 (1.78) for widescreen.

Multiple cameras

Multiple cameras may be placed side-by-side to record a single angle of a scene and repeated throughout the runtime. The film is then later projected simultaneously, either on a single three-image screen (Cinerama) or upon multiple screens forming a complete circle, with gaps between screens through which the projectors illuminate an opposite screen. (See Circle-Vision 360°) convex and concave mirrors are used in cameras as well as mirrors.

Sound synchronization

One of the problems in film is synchronizing a sound recording with the film. Most film cameras do not record sound internally; instead, the sound is captured separately by a precision audio device (see double-system recording). The exceptions to this are the single-system news film cameras, which had either an optical—or later—magnetic recording head inside the camera. For optical recording, the film only had a single perforation and the area where the other set of perforations would have been was exposed to a controlled bright light that would burn a waveform image that would later regulate the passage of light and playback the sound. For magnetic recording, that same area of the single perf 16 mm film that was prestriped with a magnetic stripe. A smaller balance stripe existed between the perforations and the edge to compensate the thickness of the recording stripe to keep the film wound evenly.

Double-system cameras are generally categorized as either "sync" or "non-sync." Sync cameras use crystal-controlled motors that ensure that film is advanced through the camera at a precise speed. In addition, they're designed to be quiet enough to not hamper sound recording of the scene being shot. Non-sync or "MOS" cameras do not offer these features; any attempt to match location sound to these cameras' footage will eventually result in "sync drift", and the noise they emit typically renders location sound recording useless.

To synchronize double-system footage, the clapper board which typically starts a take is used as a reference point for the editor to match the picture to the sound (provided the scene and take are also called out so that the editor knows which picture take goes with any given sound take). It also permits scene and take numbers and other essential information to be seen on the film itself. Aaton cameras have a system called AatonCode that can "jam sync" with a timecode-based audio recorder and prints a digital timecode directly on the edge of the film itself. However, the most commonly used system at the moment is unique identifier numbers exposed on the edge of the film by the film stock manufacturer (KeyKode is the name for Kodak's system). These are then logged (usually by a computer editing system, but sometimes by hand) and recorded along with audio timecode during editing. In the case of no better alternative, a handclap can work if done clearly and properly, but often a quick tap on the microphone (provided it is in the frame for this gesture) is preferred.

One of the most common uses of non-sync cameras is the spring-wound cameras used in hazardous special effects, known as "crash cams". Scenes shot with these have to be kept short or resynchronized manually with the sound. MOS cameras are also often used for second unit work or anything involving slow or fast-motion filming.

With the advent of digital cameras, synchronization became a redundant term, as both visual and audio is simultaneously captured electronically.

Home movie cameras

Movie cameras were available before World War II often using the 9.5 mm film format. The use of movie cameras had an upsurge in popularity in the immediate post-war period giving rise to the creation of home movies. Compared to the pre-war models, these cameras were small, light, fairly sophisticated and affordable.

An extremely compact 35 mm movie camera Kinamo was designed by Emanuel Goldberg for amateur and semi-professional movies in 1921. A spring motor attachment was added in 1923 to allow flexible handheld filming. The Kinamo was used by Joris Ivens and other avant-garde and documentary filmmakers in the late 1920s and early 1930s.[17][18]

While a basic model might have a single fixed aperture/focus lens, a better version might have three or four lenses of differing apertures and focal lengths on a rotating turret. A good quality camera might come with a variety of interchangeable, focusable lenses or possibly a single zoom lens. The viewfinder was normally a parallel sight within or on top of the camera body. In the 1950s and for much of the 1960s these cameras were powered by clockwork motors, again with variations of quality. A simple mechanism might only power the camera for some 30 seconds, while a geared drive camera might work for as long as 75 – 90 seconds (at standard speeds).

The common film used for these cameras was termed Standard 8, which was a strip of 16-millimetre wide film which was only exposed down one half during shooting. The film had twice the number of perforations as film for 16 mm cameras and so the frames were half as high and half as wide as 16 mm frames. The film was removed and placed back in the camera to expose the frames on the other side once the first half had been exposed. Once the film was developed it was sliced down the middle and the ends attached, giving 50-foot (15 m) of Standard 8 film from a spool of 25-foot (7.6 m) of 16 mm film. 16 mm cameras, mechanically similar to the smaller format models, were also used in home movie making but were more usually the tools of semi professional film and news film makers.

In the 1960s a new film format, Super8, coincided with the advent of battery-operated electric movie cameras. The new film, with a larger frame print on the same width of film stock, came in a cassette that simplified changeover and developing. Another advantage of the new system is that they had the capacity to record sound, albeit of indifferent quality. Camera bodies, and sometimes lenses, were increasingly made in plastic rather than the metals of the earlier types. As the costs of mass production came down, so did the price and these cameras became very popular.

This type of format and camera was more quickly superseded for amateurs by the advent of digital video cameras in the 2000s. Since the 2010s, amateurs increasingly started preferring smartphone cameras.

See also

- Animation camera

- Camcorder

- Camera stabilizer

- Digital movie camera

- Eyemo and Filmo

- History of cinema

- List of film formats

- Konvas

- Multiplane camera

- Debrie Parvo

- Prestwich Camera

References

- Joseph and Barbara Anderson, "The Myth of Persistence of Vision Revisited," Journal of Film and Video, Vol. 45, No. 1 (Spring 1993): 3-12. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-11-24. Retrieved 2009-11-24.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Ronalds, B.F. (2016). Sir Francis Ronalds: Father of the Electric Telegraph. London: Imperial College Press. ISBN 978-1-78326-917-4.

- Ronalds, B.F. (2016). "The Beginnings of Continuous Scientific Recording using Photography: Sir Francis Ronalds' Contribution". European Society for the History of Photography. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- "The First "Movie Camera"". Sir Francis Ronalds and his Family. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Picturing Motion in Photography: When Time Stands Still". Art21 Magazine. Retrieved 2019-11-26.

- Braun, Marta, (1992) Picturing Time: The Work of Etienne-Jules Marey (1830–1904), p. 190, Chicago: University of Chicago Press ISBN 0-226-07173-1; Robinson, David, (1997) From Peepshow to Palace: The Birth of American Film, p. 28, New York and Chichester, West Sussex, Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-10338-7)

- Spehr, Paul (2008). The Man Who Made Movies: W.K.L. Dickson. UK: John Libbey. pp. 105–111.

- Gosser (1977), pp. 206–207; Dickson (1907), part 3.

- "Polska. Informator", Wydawnictwo Interpress, Warszawa 1977 (in Polish)

- Maciej Ilowiecki, "Dzieje nauki polskiej", Wydawnictwo Interpress, Warszawa1981, ISBN 8322318766, p.202, (in Polish)

- "Polska. Zarys encyklopedyczny", PWN, Warszawa 1974 (in Polish)

- Wladyslaw Jewsiewicki, Kazimierz Prószynski, Interpress, Warsaw 1974, (in Polish)

- Alfred Liebfeld "Polacy na szlakach techniki" WKL, Warszawa 1966

- "Kazimierz Proszynski, Polish inventor". Victorian Cinema. Retrieved 2007-01-20.

- "Arthur Samuel Newman, British camera manufacturer". Victorian Cinema. Archived from the original on 12 January 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-20.

- Siede, Caroline (23 August 2018). "Maybe the war between digital and film isn't a war at all". AV Club. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

In 2017, 92 percent of films were shot on digital.

- Buckland, Michael. The Kinamo camera, Emanuel Goldberg, and Joris Ivens. In: Film History 20 (1) (2008): 49-58. http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/film_history/v020/20.1.buckland.pdf

- Ica and the Kinamo and Joris Evens. In: Buckland, Michael: Emanuel Goldberg and his Knowledge Machine. Libraries Unlimited, 2006. ISBN 0-313-31332-6. pp. 85-92 and pp. 92-95

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Movie cameras. |