Schisandra chinensis

Schisandra chinensis (common name: magnolia-vine, Chinese magnolia-vine, schisandra),[1] whose fruit is called magnolia berry[3] or five-flavor-fruit[1] (from Chinese wǔ wèi zi), is a deciduous woody vine native to forests of Northern China and the Russian Far East. It is hardy in USDA Zone 4. The plant likes some shade with moist, well-drained soil. The species itself is dioecious, thus flowers on a female plant will only produce fruit when fertilized with pollen from a male plant. However, a hybrid selection titled 'Eastern Prince' has perfect flowers and is self-fertile. Seedlings of 'Eastern Prince' are sometimes sold under the same name, but are typically single-sex plants. The fruits are red berries borne in dense hanging clusters around 10 cm long.

| Schisandra chinensis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Order: | Austrobaileyales |

| Family: | Schisandraceae |

| Genus: | Schisandra |

| Species: | S. chinensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Schisandra chinensis | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Kadsura chinensis Turcz.[1][2] | |

Growing information

Schisandra is native to northern and northeastern China (Manchuria). Cultivation requirements are thought to be similar to those of grapes.[4] Plants require conditions of moderate humidity and light, together with a wet, humus-rich soil. In order to successfully grow fruit male and female plants must be grown together.[5] Plants can be propagated by seed or by layering in spring or autumn, or in the summer time by using semi-ripe cuttings.[5] Tens of tons of berries are used annually in Russia in Primorsky Krai and Khabarovsk Krai for the commercial manufacture of juices, wines, extracts, and sweets.

Etymology

Its Chinese name comes from the fact that its berries possess all five basic flavors: salty, sweet, sour, pungent (spicy), and bitter. Sometimes, it is more specifically called běi wǔ wèi zi (literally "northern five-flavor berry") to distinguish it from another traditionally medicinal schisandraceous plant Kadsura japonica that grows only in subtropical areas. Another species of schisandra berry, Schisandra sphenanthera, has a similar but different biochemical profile; the Chinese Pharmacopeia distinguishes between S. chinensis (běi wǔ wèi zi) and S. sphenanthera (nan wǔ wèi zi).[6]

Uses

Its berries are used in traditional medicine, where it is considered one of the 50 fundamental herbs. Chemical constituents include the lignans schisandrin, deoxyschizandrin, gomisins, and pregomisin.[7]

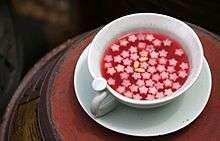

In Korean, the berries are known as omija (오미자 (hangul) – five flavours). The cordial drink made from the berries is called omija-cha, meaning "omija tea"; see Korean tea. In Japanese, they are called gomishi. The Ainu people used this plant, called repnihat, as a remedy for colds and sea-sickness.[8]

Interest in limonnik (S. chinensis) in Russia was associated with ethnopharmacological investigations by Soviet scientists on berries and seeds.[9]

Culture

In 1998, Russia released a postage stamp depicting S. chinensis.[10]

Gallery

Fruit

Fruit Seeds

Seeds Berries

Berries

Omija-cha (magnolia berry tea)

Omija-cha (magnolia berry tea) Omija-hwachae (magnolia berry punch)

Omija-hwachae (magnolia berry punch)

References

- "Schisandra chinensis". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 2008-02-19.

- "Schisandra chinensis – Plants For A Future database report". Plants for a Future. 2012. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- Moskin, Julia; Fabricant, Florence; Wells, Pete; Fox, Nick (29 November 2011). "The Year's Notable Cookbooks". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- "Magnolia vine". Bay Flora. 2016.

- Bown, Deni (1995). Encyclopedia of herbs & their uses. Montréal: RD Press. ISBN 0888503342. OCLC 32547547.

- Difference between Schisandra chinensis and Schisandra sphenanthera

- Lu, Y; Chen, D. F. (2009). "Analysis of Schisandra chinensis and Schisandra sphenanthera". Journal of Chromatography A. 1216 (11): 1980–90. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2008.09.070. PMID 18849034.

- Batchelor, John; Miyabe, Kingo (1893). "Ainu economic plants". Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan. R. Meiklejohn & Co. 51: 198–240.

- Panossian, A; Wikman, G (2008). "Pharmacology of Schisandra chinensis Bail.: An overview of Russian research and uses in medicine". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 118 (2): 183–212. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2008.04.020. PMID 18515024.

- "Russian stamp: Schisandra chinensis". 1998.