Schippia

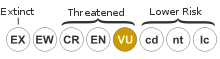

Schippia concolor, the mountain pimento or silver pimeto, is a medium-sized palm species that is native to Belize and Guatemala. Named for its discoverer, Australian botanist William A. Schipp, the species is threatened by habitat loss. It is the sole species in the genus Schippia.

| Schippia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Clade: | Commelinids |

| Order: | Arecales |

| Family: | Arecaceae |

| Subfamily: | Coryphoideae |

| Tribe: | Cryosophileae |

| Genus: | Schippia Burret |

| Species: | S. concolor |

| Binomial name | |

| Schippia concolor Burret | |

Description

Schippia concolor is a medium-sized, single-stemmed palm with fan-shaped (or palmate) leaves. The stem, which is 5 to 10 metres (16 to 33 ft) tall and 5 to 10 centimetres (2.0 to 3.9 in) in diameter, is usually covered by the remains of old, dead leaves (but in areas where fires are frequent the corky bark of the stem may be exposed throughout the length of the stem). Individuals bear six to 15 leaves which consist of a 2 m (6.6 ft) petiole and a roughly circular leaf blade which is about 1 m (3.3 ft) in diameter divided into 30 leaflets. The fruit are white, spherical and up to 2.5 cm (0.98 in) in diameter.[2]

Taxonomy

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified phylogeny of the Cryosophileae based on four nuclear genes and the matK plastid gene.[3] |

Schippia is a monotypic genus—it includes only a single species, S. concolor. In the first edition of Genera Palmarum (1987), Natalie Uhl and John Dransfield placed the genus Schippia in the subfamily Coryphoideae, the tribe Corypheae and the subtribe Thrinacinae[4] Subsequent phylogenetic analysis showed that the Old World and New World members of the Thrinacinae are not closely related. As a consequence of this, Schippia and related genera have been placed in their own tribe, Cryosophileae.[5] Within this tribe, Schippia appears to be most closely related to the genus Cryosophila.[6]

The species was discovered by Australian botanist William A. Schipp in 1932[2] and described by German taxonomist Max Burret in 1933.[7] Burret named the genus in honour of Schipp. The holotype upon which the species (and the genus) was based, was Schipp's collection, assigned the collection number S367. This specimen was destroyed when the Berlin Herbarium was bombed during the Second World War.[8]

Reproduction and growth

Schippia concolor exhibit the unusual strategy of transferring all stored resources from the seed to the seedling before any shoot growth occurs. In most plants, the seedling remains attached to the seed, gradually using the stored resources for growth, until those resources are exhausted. At that point, the connection withers, detaching the remains of the seed.[9]

Eight to nine days after the seed is hydrated, the cotyledon expands, pushes out of the seed, and grows downward into the soil. About 20 days after germination, the cotyledon reaches a length of about 15 cm (5.9 in) and begins to swell. By the thirtieth day the lower 3 or 4 cm (1.2 or 1.6 in) are swollen, and about half the reserves in the seed have been mobilised. At about this point in time, the young root (the radicle) emerges. Sixty days after germination the transfer of reserved from the seed has been completed, but it is only after 80 or 90 days that the young shoot (the plumule) emerges from the cotyledon.[9]

References

- Johnson, D. 1998. Schippia concolor. 2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 20 July 2007.

- Henderson, Andrew; Gloria Galeano; Rodrigo Bernal (1995). Field Guide to the Palms of the Americas. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-0-691-08537-1.

- Cano, Ángela; Bacon, Christine D.; Stauffer, Fred W.; Antonelli, Alexandre; Serrano‐Serrano, Martha L.; Perret, Mathieu (2018). "The roles of dispersal and mass extinction in shaping palm diversity across the Caribbean". Journal of Biogeography. 45 (6): 1432–1443. doi:10.1111/jbi.13225. ISSN 1365-2699.

- Uhl, Natalie E.; John Dransfield (1987). Genera Palmarum: a classification of palms based on the work of Harold E. Moore Jr. Lawrence, Kansas: The L. H. Bailey Hortorium and the International Palm Society.

- Dransfield, John; Natalie W. Uhl; Conny B. Asmussen; William J. Baker; Madeline M. Harley; Carl E. Lewis (2005). "A New Phylogenetic Classification of the Palm Family, Arecaceae". Kew Bulletin. 60 (4): 559–69. JSTOR 25070242.

- Roncal, Julissa; Scott Zona; Carl E. Lewis (2008). "Molecular Phylogenetic Studies of Caribbean Palms (Arecaceae) and Their Relationships to Biogeography and Conservation". Botanical Review. 74 (1): 78–102. doi:10.1007/s12229-008-9005-9.

- "Schippia concolor". World Checklist of Selected Plant Families. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- Lowden, Richard M. (1970). "William A. Schipp's Botanical Explorations in the Stann Creek and Toledo Districts, British Honduras (1929-1935)". Taxon. 19 (6): 831–861. doi:10.2307/1218298. JSTOR 1218298.

- Pinheiro, Claudio Urbano B. (2001). "Germination strategies of palms: the case of Schippia concolor Burret in Belize". Brittonia. 53 (4): 519–527. doi:10.1007/BF02809652.