Seedling

A seedling is a young plant sporophyte developing out of a plant embryo from a seed. Seedling development starts with germination of the seed. A typical young seedling consists of three main parts: the radicle (embryonic root), the hypocotyl (embryonic shoot), and the cotyledons (seed leaves). The two classes of flowering plants (angiosperms) are distinguished by their numbers of seed leaves: monocotyledons (monocots) have one blade-shaped cotyledon, whereas dicotyledons (dicots) possess two round cotyledons. Gymnosperms are more varied. For example, pine seedlings have up to eight cotyledons. The seedlings of some flowering plants have no cotyledons at all. These are said to be acotyledons.

The plumule is the part of a seed embryo that develops into the shoot bearing the first true leaves of a plant. In most seeds, for example the sunflower, the plumule is a small conical structure without any leaf structure. Growth of the plumule does not occur until the cotyledons have grown above ground. This is epigeal germination. However, in seeds such as the broad bean, a leaf structure is visible on the plumule in the seed. These seeds develop by the plumule growing up through the soil with the cotyledons remaining below the surface. This is known as hypogeal germination.

Photomorphogenesis and etiolation

Dicot seedlings grown in the light develop short hypocotyls and open cotyledons exposing the epicotyl. This is also referred to as photomorphogenesis. In contrast, seedlings grown in the dark develop long hypocotyls and their cotyledons remain closed around the epicotyl in an apical hook. This is referred to as skotomorphogenesis or etiolation. Etiolated seedlings are yellowish in color as chlorophyll synthesis and chloroplast development depend on light. They will open their cotyledons and turn green when treated with light.

In a natural situation, seedling development starts with skotomorphogenesis while the seedling is growing through the soil and attempting to reach the light as fast as possible. During this phase, the cotyledons are tightly closed and form the apical hook to protect the shoot apical meristem from damage while pushing through the soil. In many plants, the seed coat still covers the cotyledons for extra protection.

Upon breaking the surface and reaching the light, the seedling's developmental program is switched to photomorphogenesis. The cotyledons open upon contact with light (splitting the seed coat open, if still present) and become green, forming the first photosynthetic organs of the young plant. Until this stage, the seedling lives off the energy reserves stored in the seed. The opening of the cotyledons exposes the shoot apical meristem and the plumule consisting of the first true leaves of the young plant.

The seedlings sense light through the light receptors phytochrome (red and far-red light) and cryptochrome (blue light). Mutations in these photo receptors and their signal transduction components lead to seedling development that is at odds with light conditions, for example seedlings that show photomorphogenesis when grown in the dark..

Seedling growth and maturation

Once the seedling starts to photosynthesize, it is no longer dependent on the seed's energy reserves. The apical meristems start growing and give rise to the root and shoot. The first "true" leaves expand and can often be distinguished from the round cotyledons through their species-dependent distinct shapes. While the plant is growing and developing additional leaves, the cotyledons eventually senesce and fall off. Seedling growth is also affected by mechanical stimulation, such as by wind or other forms of physical contact, through a process called thigmomorphogenesis.

Temperature and light intensity interact as they affect seedling growth; at low light levels about 40 lumens/m² a day/night temperature regime of 28 °C/13 °C is effective (Brix 1972).[1] A photoperiod shorter than 14 hours causes growth to stop, whereas a photoperiod extended with low light intensities to 16 h or more brings about continuous (free) growth. Little is gained by using more than 16 h of low light intensity once seedlings are in the free growth mode. Long photoperiods using high light intensities from 10,000 to 20,000 lumens/m² increase dry matter production, and increasing the photoperiod from 15 to 24 hours may double dry matter growth (Pollard and Logan 1976, Carlson 1979).[2][3]

The effects of carbon dioxide enrichment and nitrogen supply on the growth of white spruce and trembling aspen were investigated by Brown and Higginbotham (1986).[4] Seedlings were grown in controlled environments with ambient or enriched atmospheric CO2 (350 or 750 f1/L, respectively) and with nutrient solutions with high, medium, and low N content (15.5, 1.55, and 0.16 mM). Seedlings were harvested, weighed, and measured at intervals of less than 100 days. N supply strongly affected biomass accumulation, height, and leaf area of both species. In white spruce only, the root weight ratio (RWR) was significantly increased with the low-nitrogen regime. CO2 enrichment for 100 days significantly increased the leaf and total biomass of white spruce seedlings in the high-N regime, RWR of seedlings in the medium-N regime, and root biomass of seedlings in the low-N regime.

First-year seedlings typically have high mortality rates, drought being the principal cause, with roots having been unable to develop enough to maintain contact with soil sufficiently moist to prevent the development of lethal seedling water stress. Somewhat paradoxically, however, Eis (1967a)[5] observed that on both mineral and litter seedbeds, seedling mortality was greater in moist habitats (alluvium and Aralia–Dryopteris) than in dry habitats (Cornus–Moss). He commented that in dry habitats after the first growing season surviving seedlings appeared to have a much better chance of continued survival than those in moist or wet habitats, in which frost heave and competition from lesser vegetation became major factors in later years. The annual mortality documented by Eis (1967a)[5] is instructive.

Transplanting

Seedlings are generally transplanted[8] when the first pair of true leaves appear. A shade may be provided if the area is arid or hot. A commercially available vitamin hormone concentrate may be used to avoid transplant shock which may contain thiamine hydrochloride, 1-Naphthaleneacetic acid and indole butyric acid.

Images

A few days old Scots pine seedling, the seed still protecting the cotyledons.

A few days old Scots pine seedling, the seed still protecting the cotyledons. Seedling

Seedling Seedling of Quercus robur sprouting from its acorn.

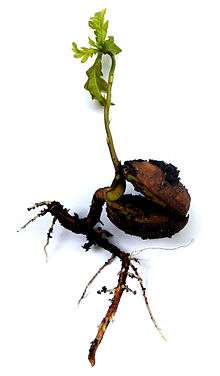

Seedling of Quercus robur sprouting from its acorn. Dicotyledon plantlet showing roots.

Dicotyledon plantlet showing roots. Seedling of Bombax species.

Seedling of Bombax species.

See also

References

- Brix, H. 1972. Growth response of Sitka spruce and white spruce seedlings to temperature and light intensity. Can. Dep. Environ., Can. For. Serv., Pacific For. Res. Centre, Victoria BC, Inf. Rep. BC-X-74. 17 p.

- Pollard, D.F.W.; Logan, K.T. 1976. Prescription for the aerial environment for a plastic greenhouse nursery. p.181–191 in Proc. 12th Lake States For. Tree Improv. Conf. 1975. USDA, For. Serv., North Central For. Exp. Sta., St. Paul MN, Gen. Tech. Rep. NC-26.

- Carlson, L.W. 1979. Guidelines for rearing containerized conifer seedlings in the prairie provinces. Can. Dep. Environ., Can. For. Serv., Edmonton AB, Inf. Rep. NOR-X-214. 62 p. (Cited in Nienstaedt and Zasada 1990).

- Brown, K.; Higginbotham, K.O. 1986. Effects of carbon dioxide enrichment and nitrogen supply on growth of boreal tree seedlings. Tree Physiol. 2(1/3):223–232.

- Eis, S. 1967a. Establishment and early development of white spruce in the interior of British Columbia. For. Chron. 43:174–177.

- Buczacki, S. and Harris, K., Pests, Diseases & Disorders of Garden Plants, HarperCollins, 1998, p115 ISBN 0-00-220063-5

- Buczacki, S. and Harris, K., Pests, Diseases & Disorders of Garden Plants, HarperCollins, 1998, p116 ISBN 0-00-220063-5

- "Garden". organicgardening.com. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

Bibliography

- P.H. Raven, R.F. Evert, S.E. Eichhorn (2005): Biology of Plants, 7th Edition, W.H. Freeman and Company Publishers, New York, ISBN 0-7167-1007-2

External links