Schiavi di Abruzzo

Schiavi di Abruzzo is a hill town in the province of Chieti, Abruzzo, central Italy. It is located in the Apennine Mountains, in the southernmost portion of the Abruzzo region, on border with the Molise region.

Schiavi | |

|---|---|

| Comune di Schiavi di Abruzzo | |

| |

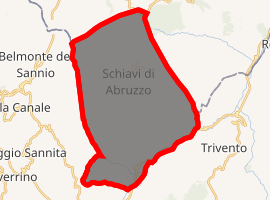

Location of Schiavi

| |

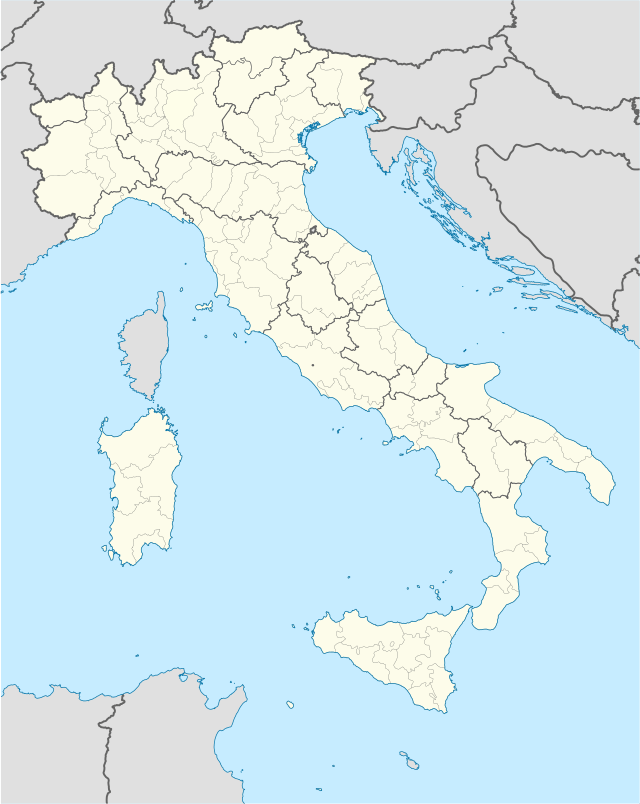

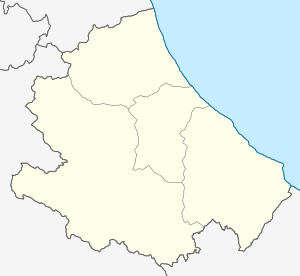

Schiavi Location of Schiavi in Italy  Schiavi Schiavi (Abruzzo) | |

| Coordinates: 41°49′N 14°29′E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | Abruzzo |

| Province | Chieti (CH) |

| Frazioni | Badia, Canali di Taverna, Cannavina, Casali, Cupello, Salce, San Martino, San Martino Superiore, Taverna, Valli, Valloni |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Luciano Piluso |

| Area | |

| • Total | 17.4 km2 (6.7 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,172 m (3,845 ft) |

| Population (30 November 2014)[2] | |

| • Total | 886 |

| • Density | 51/km2 (130/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Schiavesi |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 66045 |

| Dialing code | 0873 |

| Patron saint | Saint Maurice |

| Saint day | September 22 |

| Website | Official website |

It is 56 kilometres (35 mi), from the Adriatic Sea, and 225 kilometres (140 mi) from Rome.

Geography

The historical center of the town is situated at the highest point of a mountain peak, at 1,170 metres (3,840 ft), and there are population centers or administrative divisions in the valleys on three sides of the mountain. Three quarters of the population lives in these surrounding valleys.

Heavy snowfall can occur in winter months.[3]

Language and dialect

The town has a historical Italian dialect known as Schiavese.[4] For many centuries there have been different dialects even between towns in the same vicinity.[5] With the advent of television, the dialects have become less prevalent.

Population

The municipal boundaries cover 17.4 square miles (45 km2).

In 2014, the populations was 886.

The population in 1861 was 3,657. As was the case of the rural areas of Southern Italy, the town experienced a mass immigration (Italian diaspora) to North and South America between 1861 and 1914. This immigration lead an abrupt decline of the agricultural economy.

Nonetheless the population peaked in 1961 at 4,526. Since then there has been a steady decline due to residents having sought employment in the Italian cities (mostly Rome), and also throughout Europe.

History

The first written mention of the town dates back to Middle Ages, in the first half of the 11th century. Also, the name Schavis and Sclavi appeared in the Libro delle decime (tithe book) of 1309 and of 1328.[6] It is commonly known that there was a colony of Slavs that became a fief of Roberto da Sclavo, from which the name of the town was probably derived.

From 1130 the town was part of the Kingdom of Sicily, and later of Kingdom of Naples.

From 1626[7] until 1806[8] the town was also a fief of the Caracciolo di SantoBuono a branch the Caracciolo clan of Naples[9], and administered from San Buono, a town 34 kilometres (21 mi) away.

From 1816 to 1861, Schiavi was part of the Kingdom of Two Sicilies, then becoming part of the Kingdom of Italy, until 1946 when Italy became a democracy.

People

- Almerindo Portfolio, treasurer of New York City

Between 1917 and 1919 Portfolio paid 300,000 Lira ($1.5 million in 2006 US dollars[10]) to install the first electric service in his home town of Schiavi di Abruzzo, Italy. He later gave 50,000 Lira ($255,000 in 2006 US dollars[11]) for the town's water utilities.[12]

As evidenced by the World War I and World War II memorial, Cirulli is the most common last name, followed by Falasca.

Main Sights

- Templi Italici archaeological site. In the valley 200 metres (660 ft) below the town are the ruins of two temples dating from the period of Classical Antiquity, from about 3 BC. Known as the Templi Italici, referring to the Italic people of whom the Samnites, who lived here before the Roman conquest, were a subgroup.

- Purgatorio Park, including walks among pine trees.

- A replica of the Grotto of the Madonna of Lourdes is being constructed in the valley just below the town and the Italic Temples.

Transportation

There is daily bus service from Rome's Roma Termini railway station that takes about four hours.

By car from Rome, it takes about three hours via the A1 tollroad (Autostrade of Italy) south, in the direction of Naples. After 146 km (60 minutes) and just past Cassino, taking the San Vittore del Lazio exit, and following the signs to Isernia for 36 km (45 minutes) on state SS85. At Isernia, following signs to Vasto, and proceeding 35 km (45 minutes) on state road SS650, to the Schiavi di Abruzzo exit. SS650 is along the Trigno river and is generally at sea level. So from the exit, the road proceeds up the mountain side 13 km (20 minutes) with a 3,800-foot (1,200 m) elevation change. To see road map, click here.[14]

References

- "Superficie di Comuni Province e Regioni italiane al 9 ottobre 2011". Istat. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- "Popolazione Residente al 1° Gennaio 2018". Istat. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- "Ancient photograph contributed by L. Ninni" Archived 2008-05-14 at the Wayback Machine

- A variation of Abruzzese Orientale Adriatico (see Map of Southern Italian Dialects), which is a form of the Neapolitan language group, and a variation of Southern Italian.

- There are some towns in the region that have a Croatian influence in the dialect, a South Slavic language. Though this influence does not exist in Schiavi, it reinforces the historical origins of some of the people groups. The Slavic dialects have been preserved since a group of Christian Croats emigrated from Dalmatia, in Croatia, abreast of advancing Ottoman Turks in the period 1453–1566. See Molise Croatian dialect, second paragraph, and Expansion and apogee of the Ottoman Empire

- History section, Schiavi di Abruzzo page. Archived 2008-05-14 at the Wayback Machine www.italyheritage.com, History section..

- Genealogy of the Caracciolo di Santo Buono. Within this link, use ctrl-F to find instances of the word "Schiavi". Control began with (C20) Don Alfonso Caracciolo (1603-1660), the third Prince of Santo Buono and Count of Schiavi, in 1626. Though feudalism was abolished in 1806, the last known pretender of the fief was (L4) Don Marino Caracciolo (1910-1971), 15th Prince of Santo Buono and Count of Capracotta and Schiavi.

- Schiavi di Abruzzo, Documenti e Storia, edited by L. Porfilio and P. Falasca, Marino Saolfanelli Publishers, 1994, ISBN 88-7497-621-6. Page 194 describes the abolishment feudalism.

- The Continuity of Feudal Power: The Caracciolo Di Brienza in Spanish Naples, Tommaso Astarita, Cambridge University Press (CUP), 1991. This book centers around a different branch of the Caracciolo family involving a set of three small towns similar to Schiavi, located in the Basilicata region, southeast of Naples. Following is a description by the publisher, CUP : The Continuity of Feudal Power is an analytic study of a family of the Neapolitan aristocracy during the early modern period, with particular focus on the time of Spanish rule (1503–1707). The Caracciolo marquis of Brienza were a branch of one of the oldest and most powerful clans in the kingdom of Naples, and they numbered among the hundred wealthiest feudal families throughout the early modern period. Professor Astarita reconstructs the family's patrimony, administration and revenues, the family's relationship with the rural communities over which it had jurisdiction, its marriage and alliance policies, and the relations between the aristocracy and the monarchical government. His emphasis is on the continuing importance of feudal traditions, institutions and values both in the definition of the aristocracy's status and in its success in ensuring the persistence of its wealth and power within the kingdom. The first social history of Naples under Spanish rule • Uses a detailed study of the Caracciolo Marquis of Brienza to examine the lives of the aristocracy and their maintenance of power for three centuries. Contents: 1. The Caracciolo di Brienza; 2. Structure and evolution of an aristocratic patrimony; 3. The management of an aristocratic landed patrimony; 4. The feudal lord and his vassals: between traditional paternalism and change; 5. Aristocratic strategies for the preservation of family wealth; 6. Offices, courts and taxes, the aristocracy and the Spanish rule. Read the "first pages" provided by Amazon by putting cursor over book cover here.

- Assuming that 300,000 lira in 1918 was equivalent to $47,600, based on a 6.3 lira per dollar exchange rate as reported by The Crisis of Liberal Italy By Douglas J. Forsyth, page 205, at a time when the average family annual income was $1,518 as reported by Economic and demographic indicators, United States, 1918–19 Archived April 16, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, so the sum was 41 times average family annual income, and given that 2006 median family income was $48,800.

- Ibid, 5.2 times average family annual income.

- Schiavi di Abruzzo, Documenti e Storia, edited by L. Porfilio and P. Falasca, Marino Solfanelli Publishers, 1994, ISBN 88-7497-621-6., Page 232.

- Schiavi di Abruzzo.net retrieved 4-1-09

- Route from Rome to Schiavi di Abruzzo Google Maps.