Save (baseball)

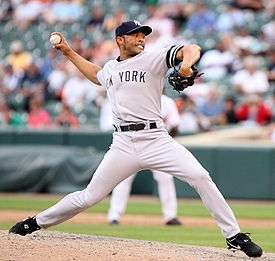

In baseball, a save (abbreviated SV or S) is credited to a pitcher who finishes a game for the winning team under certain prescribed circumstances. Most commonly a pitcher earns a save by entering in the ninth inning of a game in which his team is winning by three or fewer runs and finishing the game by pitching one inning without losing the lead.[1] The number of saves or percentage of save opportunities successfully converted are oft-cited statistics of relief pitchers, particularly those in the closer role. The save statistic was created by journalist Jerome Holtzman in 1959 to "measure the effectiveness of relief pitchers" and was adopted as an official MLB statistic in 1969.[2][3] The save has been retroactively measured for pitchers before that date. Mariano Rivera is MLB's all-time leader in regular-season saves with 652.

History

The term save was being used as far back as 1952.[4] Executives Jim Toomey of the St. Louis Cardinals, Allan Roth of the Los Angeles Dodgers and Irv Kaze of the Pittsburgh Pirates awarded saves to pitchers who finished winning games but were not credited with the win, regardless of the margin of victory. The statistic went largely unnoticed.

A formula with more criteria for saves was invented in 1960 by baseball writer Jerome Holtzman.[5] He felt that the existing statistics at the time, earned run average (ERA) and win–loss record (W-L), did not sufficiently measure a reliever's effectiveness. ERA does not account for inherited runners a reliever allows to score, and W-L record does not account for relievers protecting leads. Elroy Face of the Pittsburgh Pirates was 18–1 in 1959; however, Holtzman wrote that in 10 of the 18 wins, Face allowed the tying or lead run but got the win when the Pirates offense regained the lead.[6][note 1] Holtzman felt that Face was more effective the previous year when he was 5–2. When Holtzman presented the idea to J. G. Taylor Spink, publisher of The Sporting News, "[Spink] gave [Holtzman] a $100 bonus. Maybe it was $200." Holtzman recorded the unofficial save statistic in The Sporting News weekly for nine years before it became official in 1969. In conjunction with publishing the statistic, The Sporting News in 1960 also introduced the Fireman of the Year Award, which was awarded based on a combination of saves and wins.[6][9]

The save became an official MLB statistic in 1969.[6] It was MLB's first new major statistic since the run batted in was added in 1920.[6] Bill Singer is credited with recording the first official save when he pitched three shutout innings in relief of Don Drysdale in the Los Angeles Dodgers' 3–2 Opening Day victory over the Cincinnati Reds at Crosley Field on April 7 of that year.[10][11]

Usage

In baseball statistics, the term save is used to indicate the successful maintenance of a lead by a relief pitcher, usually the closer, until the end of the game. A save is a statistic credited to a relief pitcher, as set forth in Rule 9.19 of the Official Rules of Major League Baseball. That rule states the official scorer shall credit a pitcher with a save when such pitcher meets all four of the following conditions:[12]

- He is the finishing pitcher in a game won by his team;

- He is not the winning pitcher;

- He is credited with at least ⅓ of an inning pitched; and

- He satisfies one of the following conditions:

If a relief pitcher satisfies all of the criteria for a save, except he does not finish the game, he will often be credited with a hold (which is not an officially recognized statistic by Major League Baseball).

A blown save (abbreviated BSV, BS or B) is charged to a pitcher who enters a game in a situation which permits him to earn a save (a save situation or save opportunity), but who instead allows the tying run to score. Note that if the tying run was scored by a runner who was already on base when the new pitcher entered the game, that new pitcher will be charged with a blown save even though the run will not be charged to the new pitcher, but rather to the pitcher who allowed that runner to reach base. If the reliever allows the tying or leading run, but the reliever's team wins the game, the reliever wins the game. Due to this definition, a pitcher cannot blow multiple saves in a game unless he has multiple save opportunities, a situation only possible when a pitcher temporarily switches defensive positions. The blown save was introduced by the Rolaids Relief Man Award in 1988.[13] A pitcher who enters the game in a save situation and does not finish the game—but his team still leading—is not charged with a save opportunity. Save percentage is the ratio of saves to save opportunities.[14]

In 1974, tougher criteria were adopted for saves where the tying run had to be on base or at the plate when the reliever entered to qualify for a save (unless he pitched three innings).[15] This addressed saves such as Ron Taylor's in a 20–6 New York Mets win over the Atlanta Braves.[16][17] The rule was relaxed in 1975 to credit a save when a reliever pitches at least one inning with no more than a three-run lead, or comes in with runners on base but the tying run on deck.[18] In 2000, Rolaids started recording a tough save when a pitcher enters a save situation with the potential tying run already on base, but still earns the save.[15]

Value

As Francisco Rodríguez pursued the single-season saves record in 2008, Baseball Prospectus member Joe Sheehan, Sports Illustrated writer Tom Verducci, and The New York Sun writer Tim Marchman wrote that Rodríguez's save total was enhanced by the number of opportunities his team presented, allowing him to amass one particular statistic. They thought that Rodríguez on his record-breaking march was less effective than in prior years.[19][20][21] Sheehan offered that saves did not account for a pitcher's proficiency at preventing runs nor did it reflect leads that were not preserved.[19]

Bradford Doolittle of The Kansas City Star wrote, "[The closer] is the only example in sports of a statistic creating a job." He decried the best relievers pitching fewer innings starting in the 1980s with their workload being reduced from two- to one-inning outings while less efficient pitchers were pitching those innings instead.[22] ESPN.com columnist Jim Caple has argued that the save statistic has turned the closer position into "the most overrated position in sports".[23] Caple and others contend that using one's best reliever in situations such as a three-run lead in the ninth—when a team will almost certainly win even with a lesser pitcher—is foolish, and that using a closer in the traditional fireman role exemplified by pitchers such as Goose Gossage is far wiser. (A "fireman" situation is men on base in a tied or close game, hence a reliever ending such a threat is "putting out the fire.")[23][24]

Firemen frequently pitched two- or three-inning outings to earn saves. The modern closer, reduced to a one-inning role, is available to pitch more save opportunities. In the past, a reliever pitching three innings one game would be unavailable to pitch the next game.[25] Gossage had more saves of at least two innings than saves where he pitched one inning or less.[26] "The times I did a one-inning save, I felt guilty about it. It's like it was too easy", said Gossage.[27] ESPN.com wrote that saves have not been determined to be "a special, repeatable skill—rather than simply a function of opportunities".[28] It also noted that blown saves are "non-qualitative", pointing out that the two career leaders in blown saves—Gossage (112) and Rollie Fingers (109)—were both inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.[28] Fran Zimniuch in Fireman: The Evolution of the Closer in Baseball wrote, "But you have to be a great relief pitcher to blow that many saves. Clearly, [Gossage] saved many, many more than he did not save."[29] More than half of Gossage's and Fingers' blown saves came in tough save situations, where the tying run was on base when the pitcher entered. In nearly half of their blown tough saves, they entered the game in the sixth or seventh inning. Multiple-inning outings provide more chances for a reliever to blow a save. The pitchers need to get out of the initial situation and pitch additional innings with more chances to lose the lead. A study by the Baseball Hall of Fame[note 2] found modern closers were put into fewer tough save situations compared to past relievers.[note 3] The modern closer also earned significantly more "easy saves", defined as saves starting the ninth inning with more than a one-run lead.[note 4][15] The study offered "praise to the combatants who faced more danger for more innings."[15]

Nate Silver of FiveThirtyEight has suggested the "goose egg," a new statistic that he considers to be a better evaluation of relief performance than the save. A reliever earns a goose egg for each scoreless inning pitched (no earned or unearned runs, no inherited runners score) in the seventh inning or later, where when he starts the inning: the score is tied, his team holds a lead of no more than two runs, or the tying run is on base or at the plate. Should the reliever be charged with an earned run in a goose egg situation, he will be credited with a "broken egg", the counterpart of the blown save, unless he finishes the game. The statistic is named for Gossage, who is the all-time leader in goose eggs but recorded relatively few saves compared to modern closers.[30]

On September 3, 2002, the Texas Rangers won 7-1 over the Baltimore Orioles as Joaquín Benoit pitched a seven-inning save, the longest save since it became an official statistic in 1969.[31][note 5] Benoit relieved Todd Van Poppel (who entered the game in the first inning after starter Aaron Myette was ejected for throwing at Melvin Mora) at the start of the third inning, and finished the game while allowing just one hit. The official scorer credited the win to Van Poppel and not Benoit, a decision that was also supported by Texas manager Jerry Narron.[34]

On August 22, 2007, Wes Littleton earned a save with the largest winning margin ever, pitching the last three innings of a 30–3 Texas Rangers win over the Baltimore Orioles. Littleton entered the game with a 14–3 lead, and the final 27-run differential broke the previous record for a save by eight runs. The New York Times noted that "there are the preposterous saves, of which Littleton's now stands out as No. 1."[35]

On October 29, 2014, Madison Bumgarner of San Francisco Giants recorded the longest save in World Series history, pitching five scoreless innings of relief in a Game 7 3-2 victory over the Kansas City Royals.[36]

Leaders in Major League Baseball

Saves

The statistic was formally introduced in 1969,[6] although research has identified saves earned prior to that point.[37]

- Key

| Player | Name of the player |

| Saves | Career saves |

| Years | The years this player played in the major leagues |

| † | Elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame |

| * | Denotes pitcher who is still active |

| L | Denotes pitcher who is left-handed |

Most saves in a career

Listed are the Major League Baseball players with the most saves in their career.

Stats updated through 2019 season

| Regular season | ||

|---|---|---|

| Player | Saves | Years |

| Mariano Rivera† | 652 | 1995–2013 |

| Trevor Hoffman† | 601 | 1993–2010 |

| Lee Smith† | 478 | 1980–1997 |

| Francisco Rodríguez | 437 | 2002–2017 |

| John FrancoL | 424 | 1984–2005 |

| Billy WagnerL | 422 | 1995–2010 |

| Dennis Eckersley† | 390 | 1975–1998 |

| Joe Nathan | 377 | 1999–2016 |

| Jonathan Papelbon | 368 | 2005–2016 |

| Jeff Reardon | 367 | 1979–1994 |

Most in a single season

Stats updated through 2019 season

| Regular season | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Player | Saves | Team | Year |

| Francisco Rodríguez | 62 | Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim | 2008 |

| Bobby Thigpen | 57 | Chicago White Sox | 1990 |

| Edwin Díaz* | Seattle Mariners | 2018 | |

| John Smoltz† | 55 | Atlanta Braves | 2002 |

| Éric Gagné | Los Angeles Dodgers | 2003 | |

| Randy MyersL | 53 | Chicago Cubs | 1993 |

| Trevor Hoffman† | San Diego Padres | 1998 | |

| Mariano Rivera† | New York Yankees | 2004 | |

| Éric Gagné | 52 | Los Angeles Dodgers | 2002 |

| Dennis Eckersley† | 51 | Oakland Athletics | 1992 |

| Rod Beck | Chicago Cubs | 1998 | |

| Jim Johnson | Baltimore Orioles | 2012 | |

| Mark Melancon* | Pittsburgh Pirates | 2015 | |

| Jeurys Familia* | New York Mets | 2016 | |

Most consecutive without a blown save

Stats updated through 2019 season

| Regular season | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Player | Saves | Team(s) | Years | Ref |

| Éric Gagné | 84 | Los Angeles Dodgers | 2002–2004 | [38] |

| Zack BrittonL* | 60 | Baltimore Orioles | 2015–2017 | [39] |

| Tom Gordon | 54 | Boston Red Sox | 1998–1999 | [38] |

| Jeurys Familia* | 52 | New York Mets | 2015–2016 | [40] |

| José Valverde | 51 | Detroit Tigers | 2010–2011 | [41] |

| John Axford* | 49 | Milwaukee Brewers | 2011–2012 | [42] |

| Brad Lidge | 47 | Houston Astros, Philadelphia Phillies | 2007–2009 | [38] |

| Grant Balfour | 44 | Oakland Athletics | 2012–2013 | [43] |

| Brad Ziegler | 43 | Arizona Diamondbacks | 2015–2016 | [44] |

| Rod Beck | 41 | San Francisco Giants | 1993–1995 | [38] |

| Trevor Hoffman† | San Diego Padres | 1997–1998 | [38] | |

| Heath Bell | San Diego Padres | 2010–2011 | [38] | |

Blown saves

Career

Stats updated through 2007 season[45]

| Regular season | ||

|---|---|---|

| Player | Blown saves | Years |

| Goose Gossage† | 112 | 1972–1994 |

| Rollie Fingers† | 109 | 1968–1985 |

| Lee Smith† | 103 | 1980–1997 |

| Bruce Sutter† | 101 | 1976–1988 |

| John FrancoL | 1984–2004 | |

| Sparky LyleL | 95 | 1967–1982 |

| Roberto Hernández | 94 | 1991–2007 |

| Jeff Reardon | 85 | 1979–1994 |

| Gene Garber | 83 | 1969–1988 |

| Kent Tekulve | 81 | 1974–1989 |

| Gary LavelleL | 1974–1987 | |

Single season

Stats updated through 2007 season[46]

| Regular season | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Player | Blown saves | Team | Year |

| Gerry Staley | 14 | Chicago White Sox | 1960 |

| Rollie Fingers† | Oakland Athletics | 1976 | |

| Bruce Sutter† | Chicago Cubs | 1978 | |

| Bob Stanley | Boston Red Sox | 1983 | |

| Ron Davis | Minnesota Twins | 1984 | |

| John HillerL | 13 | Detroit Tigers | 1976 |

| Goose Gossage† | New York Yankees | 1983 | |

| Jeff Reardon | Montréal Expos | 1986 | |

| Dan PlesacL | Milwaukee Brewers | 1987 | |

| Dave RighettiL | New York Yankees | 1987 | |

Notes

- Baseball-Reference.com differs slightly and recorded it occurring in only seven of the 18 wins. Face blew leads in his wins four times (April 24, May 14, June 11, and July 12), allowed lead runs in tie games he won three times (April 22, Aug 30, and Sept 19), and allowed an additional run while already behind in a win once (Aug 9).[7] Associated Press also reported Face allowing a tying run to score in his July 9 win over the Chicago Cubs.[8]

- The March 2006 study analyzed the career saves of Rollie Fingers, Goose Gossage, Bruce Sutter, Lee Smith, Dennis Eckersley, Trevor Hoffman, and Mariano Rivera. Hoffman and Rivera were still active, and had 436 and 379 career saves, respectively, at that time.

- Tough save opportunities (tough saves + tough blown saves): Fingers (161). Gossage (138), Hoffman (49), Rivera (46).

- Easy saves: Hoffman (261), Rivera (235), Fingers (114), Gossage (113).

- Benoit bested the previous record of six innings by Horacio Piña of the Rangers in 1972.[32] Baseball-Reference.com retroactively credited eight-inning saves to pitchers prior to 1969 including Jim Shaw (1920), Guy Morton (1920), and Dick Hall (1961).[33]

References

- Horneman, Tim (March 23, 2010). "Baseball Save Rules". livestrong.com. Retrieved August 31, 2011.

- Weber, Bruce (July 22, 2008). "Jerome Holtzman, 82, 'Dean' of Sportswriters, Dies". The New York Times. Retrieved March 13, 2013.

- Bloom, Barry (July 21, 2008). "Legendary historian Holtzman passes". MLB.com. Major League Baseball. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved March 13, 2013.

- Newman, Mark (July 22, 2008). "Holtzman helped 'save' baseball". MLB.com. Archived from the original on August 24, 2013.

- Holtzman, Jerome (September 16, 2003). "How the save formula began". MLB.com. Archived from the original on March 19, 2010.

- Holtzman, Jerome (May 2002). "Where did save rule come from? Baseball historian recalls how he helped develop statistic that measures reliever's effectiveness". Baseball Digest. Archived from the original on 2012-07-08. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- "Roy Face 1959 Pitching Gamelogs". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on November 10, 2012.

- Wilks, Ed (July 10, 1959). "Dodger' Craig Old Self Again; Two Double Shutouts in American League". The Florence Times. Alabama. Associated Press. Section 2, Page 3. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- Zimniuch, Fran (2010). Fireman: The Evolution of the Closer in Baseball. Chicago: Triumph Books. p. 125. ISBN 978-1-60078-312-8.

- "Famous Firsts in the Expansion Era of Major League Baseball by Baseball Almanac". Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- "Retrosheet Boxscore: Los Angeles Dodgers 3, Cincinnati Reds 2". Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- "Divisions Of The Code" (PDF). Retrieved 2019-06-04.

- "About The Award". McNeil Consumer Healthcare Division of McNeil-PPC, Inc. Archived from the original on January 23, 2012.

- Dickson, Paul (2011). The Dickson Baseball Dictionary. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 120, 741. ISBN 978-0-393-34008-2.

- Schechter, Gabriel (March 21, 2006). "Top Relievers in Trouble". National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Archived from the original on June 8, 2007.

- Zimniuch 2010, p.126

- "August 7, 1971 New York Mets at Atlanta Braves Box Score and Play by Play". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- "Baseball changes rule". Lewiston Morning Tribune. Associated Press. January 31, 1975. p. 3B.

- Sheehan, Joe (September 11, 2008), "Prospectus Today: Closing In", BaseballProspectus.com, archived from the original on February 13, 2010

- Verducci, Tom (July 22, 2008). "What would my idol say about K-Rod's chase of the saves record?". SI.com. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- Marchman, Tim (July 22, 2008). "K-Rod May Be Baseball's First 60-Save Man". The New York Sun. Retrieved October 5, 2011.

Half of the Angels' games so far this year have offered a save opportunity, much higher than the typical team's rate, because they play a lot of close games, having only outscored their opponents 429-396.

- Doolittle, Bradford (July 28, 2008). "Wishing that baseball's save statistic had never been invented". The Kansas City Star. Archived from the original on July 29, 2008. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

Prior to the save, there was no such thing as a closer in baseball. It is the only example in sports of a statistic creating a job — a well-paying job. But that's not my issue with the save.

- Caple, Jim (August 5, 2008). "The most overrated position in sports". ESPN.com. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011.

- Passan, Jeff (April 26, 2010). "Should managers play Scrabble with relievers?". Yahoo! Sports. Archived from the original on January 19, 2012.

- Zimniuch 2010, pp.xxvi,158–9

- Schecter, Gabriel (January 18, 2006). "The Evolution of the Closer". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on June 8, 2007.

Gossage and Fingers weren't far behind, with Fingers the only pitcher who pitched at least three innings in more than 10% of his saves. Sutter and Gossage had more saves where they logged at least two innings than saves where they pitched an inning or less.

- Zimniuch 2010, p.99

- Philip, Tom (April 30, 2011). "Blown saves are overblown". ESPN.com. Archived from the original on August 8, 2011.

- Zimniuch 2010, p.98

- Silver, Nate. "The Save Ruined Relief Pitching. The Goose Egg Can Fix It". FiveThirtyEight.

- Beck, Jason (April 6, 2013). "Smyly's long save has nothing on Benoit". MLB.com. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- "AL roundup: Benoit gets 7-inning save against O's". Deseret News. Associated Press. September 4, 2002. Archived from the original on May 6, 2015.

- "From 1916 to 2013, Recorded Save, (requiring IPouts>=21), sorted by smallest IP". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved April 25, 2013.(subscription required)

- "Rangers MLBeat: Narron pleased". mlb.com. Archived from the original on June 9, 2003. Retrieved April 15, 2007.

- Spousta, Tom (August 23, 2007). "With a 27-Run Cushion, a Save Is in the Books". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 5, 2015.

- "Did you know: Madison Bumgarner makes history". Major League Baseball. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- Armour, Mark L.; Levitt, David R. (2004). Paths to Glory: How Great Baseball Teams Got That Way. Potomac Books. pp. 92–93. ISBN 9781574888058. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- Center, Bill (May 4, 2011). "Pregame Preview: Will Bell set Padres saves record?". San Diego Union-Tribune. Archived from the original on May 5, 2011.

- Zucker, Joseph (July 23, 2017). "Zach Britton Sets AL Record After Converting 55th-Straight Save Opportunity". Bleacher Report.

- "Mets' Jeurys Familia: Cruises to 24th save". RotoWite Staff. June 22, 2016.

- "Tigers edge Red Sox after José Valverde blows save". ESPN.com. Associated Press. April 5, 2012. Archived from the original on April 7, 2012.

- "Corey Hart, Brewers edge Cubs in 13 innings". ESPN.com. Associated Press. May 12, 2012. Archived from the original on May 15, 2012.

- "Tommy Milone carries shutout into 9th, then A's hold on". ESPN.com. Associated Press. July 5, 2013. Archived from the original on July 11, 2013.

- Magruder, Jack (June 12, 2016). "For Brad Ziegler, sealing a win includes SEALs". todaysknuckleball.com.

- Gillette, Gary; Palmer, Pete; Gammons, Peter (2008). The ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia (Fifth ed.). Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. p. 1770. ISBN 978-1-4027-6051-8.

- Gillette, Palmer, Gammons 2008, p.1788