Sancho III of Pamplona

Sancho Garcés III (c. 992-996 – 18 October 1035), also known as Sancho the Great (Spanish: Sancho el Mayor, Basque: Antso Gartzez Nagusia), was the King of Pamplona from 1004 until his death in 1035. He also ruled the County of Aragon and by marriage the counties of Castile, Álava and Monzón. He later added the counties of Sobrarbe (1015), Ribagorza (1018) and Cea (1030), and would intervene in the Kingdom of León, taking its eponymous capital city in 1034.

| Sancho III | |

|---|---|

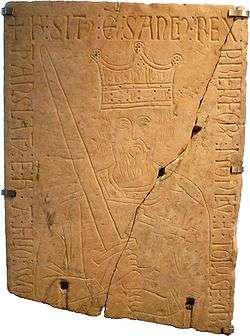

The burial stone of Sancho III, bearing his effigy | |

| King of Pamplona | |

| Tenure | 1004–1035 |

| Predecessor | García Sánchez II |

| Successor | García Sánchez III |

| Count of Aragon | |

| Tenure | 1004–1035 |

| Predecessor | García Sánchez II |

| Successor | Ramiro I |

| Born | c. 992-996 |

| Died | c. 1035 |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | Muniadona of Castile |

| Issue | Garcia III of Pamplona Ferdinand I of León Jimena Gonzalo (illegitimate) Ramiro I of Aragon |

| House | House of Jiménez |

| Father | García Sánchez II |

| Mother | Jimena Fernández |

| Religion | Catholicism |

He was the eldest son of García Sánchez II and his wife Jimena Fernández.

Biography

Birth and succession

The year of Sancho's birth is not known, but it is no earlier than 992 and no later than 996. His parents were García Sánchez II the Tremulous and Jimena Fernández, daughter of Fernando Bermúdez, count of Cea on the Leonese frontier. García and Jimena are first recorded as married in 992, but there is no record of their son Sancho until 996. The first record of the future king is a diploma of his father's granting the village of Terrero to the monastery of San Millán de la Cogolla. The king describes Sancho merely as "my son" (filius meus). The same diploma also shows the future duke of Gascony, Sancho VI, at the court of Pamplona.[1]

Sancho was raised in Leyre. His father last appears in 1000, while Sancho is first found as king in 1004, inheriting the kingdom of Pamplona (later known as Navarre). This gap has led to speculation as to whether there was an interregnum, while one document shows Sancho Ramírez of Viguera reigning in Pamplona in 1002, perhaps ruling as had Jimeno Garcés during the youth of García Sánchez I three generations earlier. On his succession, Sancho initially ruled under a council of regency led by the bishops, his mother Jimena, and grandmother Urraca Fernández.

Pyrenean politics

Sancho aspired to unify the Christian principalities in the face of the fragmentation of Muslim Spain into the taifa kingdoms following the Battle of Calatañazor. In about 1010 he married Muniadona of Castile, daughter of Sancho García of Castile, and in 1015 he began a policy of expansion. He displaced Muslim control in the depopulated former county of Sobrarbe. In Ribagorza, another opportunity arose. The 1010 partition of the county left it divided between William Isarn, illegitimate son of count Isarn, and Raymond III of Pallars Jussà and his wife, Mayor García of Castile, who was both niece of Isarn and aunt of Sancho's wife. In 1018, William Isarn tried to solidify his control over the Arán valley, but was killed, and Sancho jumped on the opportunity to take his portion, presumably based on some loose claim derived from his wife. Raymond and Mayor annulled their marriage, creating a further division finally resolved in 1025 when Mayor retired to a Castilian convent and Sancho received the submission of Raymond as vassal.[2] He also forced Berengar Raymond I of Barcelona to become his vassal, though he was already a vassal of the French king. Berengar met Sancho in Zaragoza and in Navarre many times to confer on a mutual policy against the counts of Toulouse.

Acquisition of Castile

In 1016, Sancho fixed the border between Navarre and Castile, part of the good relationship he established by marrying Muniadona, daughter of Sancho García of Castile. In 1017, he became the protector of Castile for the young García Sánchez. However, relations between the three Christian entities of León, Castile, and Navarre soured after the assassination of Count García in 1027. He had been betrothed to Sancha, daughter of Alfonso V, who was set thus to gain from Castile lands between the rivers Cea and Pisuerga (as the price for approving the marital pact). As García arrived in León for his wedding, he was killed by the sons of a noble he had expelled from his lands.

Sancho III had opposed the wedding and the expected expansion of Leonese power to Castile, and used García's death to reverse this. Using the pretext of the protectorship he had exercised over Castile, he immediately occupied the county and named as successor his own younger son Ferdinand, who was nephew of the deceased count, bringing it fully within his sphere of influence.

Gascon suzerainty

Sancho established relations with the Duchy of Gascony, probably of a suzerain–vassal nature, him being the suzerain.[3] In consequence of his relationship with the monastery of Cluny, he improved the road from Gascony to León. This road would begin to bring increased traffic down to Iberia as pilgrims flocked to Santiago de Compostela. Because of this, Sancho ranks as one of the first great patrons of the Saint James Way.

Sancho VI of Gascony was a relative of King Sancho and spent a portion of his life at the royal court in Pamplona. He also partook alongside Sancho the Great in the Reconquista. In 1010, the two Sanchos appeared together with Robert II of France and William V of Aquitaine, neither of whom was the Gascon duke's suzerain, at Saint-Jean d'Angély. After Sancho VI's death in 1032, Sancho the Great extended his authority definitively into Gascony, where he began to mention his authority as extending as far as the Garonne in the documents issued by his chancery.

In southern Gascony, Sancho created a series of viscounties: Labourd (between 1021 and 1023), Bayonne (1025), and Baztán (also 1025).

Acquisition of León

After the succession of Bermudo III to León, Sancho negotiated the marriage of his son Ferdinand to Sancha, the former fiancée of García Sánchez and Bermudo's sister, and along with it a dowry that included disputed Leonese lands. Sancho was soon engaged in a full-scale war with León, and combined Castilian and Navarrese armies quickly overran much of Bermudo's kingdom, occupying Astorga. By March 1033, he was king from Zamora to the borders of Barcelona.

In 1034, even the city of León, the imperiale culmen (imperial capital, as Sancho saw it), fell, and there Sancho had himself crowned again. This was the height of Sancho's rule which now extended from the borders of Galicia in the west to the county of Barcelona in the east. In 1035, he refounded the diocese of Palencia, which had been laid waste by the Moors. He gave the see and its several abbacies to Bernard, of French or Navarrese origin, to whom he also gave the secular lordship (as a feudum), which included many castles in the region. However, he died on 18 October 1035 and was buried in the monastery of San Salvador de Oña, an enclave in Burgos, under the inscription Sancius, gratia Dei, Hispaniarum rex.

Succession

Before his death in 1035, Sancho divided his possessions among his sons. Of the three surviving sons by Muniadona, the eldest, García, had already appeared as regulus in Navarre, inheriting the kingdom including the Basque country as well as exercising suzerainty over the kingdom's lands given to his brothers. Gonzalo had been placed in control of the counties of Sobrarbe and Ribagorza, which he would hold as regulus. Ferdinand had been given Castile on the death of count García Sánchez in 1027, holding it first under his father and later of Vermudo III of León, before killing that king to take León and the royal title. Ramiro, the eldest but illegitimate son of Sancho by mistress Sancha of Aybar, was given property in the former county of Aragón with the provision that he should ask for no more lands of García, under whom he first acted as baiulus but from whom he later achieved de facto independence. Documents report two further sons, a second Ramiro and Bernard, but scholarship is divided on whether they were legitimate sons who died in youth, or if their appearance instead results from either scribal error or forgery. Sancho left two daughters, Mayor and Jimena, the former perhaps the wife of Pons, Count of Toulouse, the latter wife of Vermudo III.

Legacy

Taking residence in Nájera instead of the traditional capital of Pamplona, as his realm grew larger, he considered himself a European monarch, establishing relations on the other side of the Pyrenees.

He introduced French feudal theories and ecclesiastic and intellectual currents into Iberia. Through his close ties with the count of Barcelona and the duke of Gascony and his friendship with the monastic reformer Abbot Oliva, Sancho established relations with several of the leading figures north of the Pyrenees, most notably Robert II of France, William V of Aquitaine, William II and Alduin II of Angoulême, and Odo II of Blois and Champagne.[4] It was through this circle that the Cluniac reforms first probably influenced his thinking. In 1024 a Navarrese monk, Paterno of San Juan de la Peña from Cluny, returned to Navarre and was made abbot of San Juan de la Peña, where he instituted the Cluniac custom and founded thus the first Cluniac house in Iberia west of Catalonia, under the patronage of Sancho. The Mozarabic rite continued to be practiced at San Juan, and the view that Sancho spread the Cluniac usage to other houses in his kingdom has been discredited by Justo Pérez de Urbel. Sancho sowed the seeds of the Cluniac reform and of the adoption of the Roman rite, but he did not widely enact them.

Sancho also began the Navarrese series of currency by minting what the Encyclopædia Britannica calls "deniers of Carolingian influence." The division of his realm upon his death, the concepts of vassalage and suzerainty, and the use of the phrase "by the grace of God" (Dei gratia) after his title were imported from France, with which he tried to maintain relations. For this he has been called the "first Europeaniser of Iberia."[5]

His most obvious legacy, however, was the temporary union of all Christian Iberia. At least nominally, he ruled over León, the ancient capital of the kingdom won from the Moors in the eighth century, and Barcelona, the greatest of the Catalan cities. Though he divided the realm at his death, thus creating the enduring legacy of Castilian and Aragonese kingdoms, he left all his lands in the hands of one dynasty, the Jiménez, which kept the kingdoms allied by blood until the twelfth century. He made the Navarrese pocket kingdom strong, politically stable, and independent, preserving it for the remainder of the Middle Ages. It is for this that his seal has been appropriated by Basque nationalism. Though, by dividing the realm, he isolated the kingdom and inhibited its ability to gain land at the expense of the Moslems. Summed up, his reign defined the political geography of Iberia until its union under the Catholic Monarchs.

Titles

Throughout his long reign, Sancho used a myriad of titles. After his coronation in León, he styled himself rex Dei gratia Hispaniarum, or "by the grace of God, king of the Spains", and may have minted coins with the legend "NAIARA/IMPERATOR".[lower-alpha 1] The use of the first title implied his kingship over all the independently founded Iberian kingdoms and the use of the form Dei gratia, adopted from French practice, stressed that his right to rule was of divine origin and sustenance. The latter, imperial title was only rarely employed, for it is not documented, being found only on coins only probably datable to his reign. It is not unlikely, however, that he desired to usurp the imperial title which the kings of León had thitherto carried.[5]

Despite this, the contemporary ecclesiastic Abbot Oliva only ever acknowledged Sancho as rex Ibericus or rex Navarrae Hispaniarum, while he called both Alfonso V and Vermudo III emperor. The first title considers Sancho as king of all Iberia, as does the second, though it stresses his kingship over Navarre alone as if it had been extended to authority over the whole Christian portion of the peninsula. The near-contemporary writer Ibn Bassam, besides highlighting his virtues, calls him Lord of the Basques.[6]

Marriage and family

| Ancestors of Sancho III of Pamplona[7] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sancho III was married to Muniadona of Castile, daughter of Sancho García of Castile, count of Castile and Álava. They had the following children:

- García Sánchez III, nicknamed "the one from Nájera", King of Pamplona from 1035 until his death in 1054 and married to Stephanie of Foix.

- Fernando Sánchez, nicknamed "the Great", already Count of Castile, he became King of León from 1037 until his 1065 death, being Emperor of all Spain from 1056, married to Sancha of León.

- Jimena Sánchez, Queen consort of León by her marriage to Bermudo III of León.[8]

- Gonzalo Sánchez, petty king of Sobrarbe and Ribagorza.

Before marrying Muniadona of Castile, Sancho III had a son with Sancha of Aibar:

- Ramiro Sánchez, initially receiving lands in Aragon, he would come to be viewed as the first King of Aragon after succeeding to his brother Gonzalo's lands, he died in 1063.

Notes

- These are usually attributed to Sancho III, although Ubieto Arteta attributes them to his ancestor Sancho I.

References

- Martínez Díez 2007, pp. 38–39.

- Martínez Díez 2007, pp. 81–89.

- Collins 1990.

- Donovan 1958, p. 22.

- Menéndez Pidal 1929.

- Pescador Medrano, Aitor. "Antso Nagusiaren ondarea". Euskal Herria XI. mendean. Nabarralde - Pamiela: 141.

- Salas Merino 2008, pp. 216-218.

- Salazar y Acha 1988, pp. 183-192.

Sources

- Besga Marroquín, Armando (2003). "Sancho III el Mayor, un rey pamplonés e hispano". Historia. 16 (327): 42–71.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bishko, Charles Julian. "Fernando I and the Origins of the Leonese–Castilian Alliance with Cluny". Studies in Medieval Spanish Frontier History (PDF). London: Variorum Reprints. pp. 1–66. Originally published in Spanish in Cuadernos de Historia de España 47 (1968): 31–135 and 48 (1969): 30–116.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bull, Marcus Graham (1993). Knightly Piety and the Lay Response to the First Crusade: The Limousin and Gascony, c. 970–c. 1130. Oxford: Clarendon Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cañada Juste, Alberto (1988). "Un posible interregno en la monarquía pamplonesa (1000–1004)". Príncipe de Viana. Anejo. 8: 15–18. ISSN 1137-7054.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Collins, Roger (1990). The Basques. London: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9780631175650.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Donovan, Richard B. (1958). Liturgical Drama in Medieval Spain. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies. ISBN 9780888440044.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Higounet, Charles (1963). Bordeaux pendant le haut moyen âge. Bordeaux: Fédération Historique de Sud-Ouest. OCLC 2272117.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ibarra y Rodríguez, Eduardo (1942). "La reconquista de los Estados pírenaicos hasta la muerte de don Sancho el Mayor (1034)". Hispania. 2 (6): 3–63.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mann, Janice (2003). "A New Architecture for a New Order: The Building Projects of Sancho el Mayor (1004–1035)". In Hiscock, Nigel (ed.). The White Mantle of Churches. Turnhout: Brepols. pp. 233–248. ISBN 978-2-503-51230-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martínez Díez, Gonzalo (2007). Sancho III el Mayor Rey de Pamplona, Rex Ibericus (in Spanish). Madrid: Marcial Pons Historia. ISBN 978-84-96467-47-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Menéndez Pidal, Ramón (1929). La España del Cid (in Spanish). Madrid: Editorial Plutarco. OCLC 1413407.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martín Duque, Ángel J. (2002). "Del reino de Pamplona al reino de Navarra" (PDF). Príncipe de Viana (in Spanish). 63 (227): 841–850. ISSN 0032-8472.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Salas Merino, Vicente (2008). La Genealogía de Los Reyes de España [The Genealogy of the Kings of Spain] (in Spanish) (4th ed.). Madrid: Editorial Visión Libros. pp. 216–218. ISBN 978-84-9821-767-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Salazar y Acha, Jaime de (1988). "Una hija desconocida de Sancho el Mayor". Príncipe de Viana, Anejo (in Spanish) (8): 183–192. ISSN 1137-7054.

- Ubieto Arteta, Antonio (1960). "Estudios en torno a la división del Reino por Sancho el Mayor de Navarra" (PDF). Príncipe de Viana (in Spanish). 21 (80–81): 5–56, 163–236. ISSN 0032-8472.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sancho III of Navarre. |

| Preceded by García Sánchez II |

King of Pamplona 1004–1035 |

Succeeded by García Sánchez III |

| Vacant | Count of Sobrarbe 1015–1035 |

Succeeded by Gonzalo |

| Preceded by William Isarn, Raymond III of Pallars, Mayor García |

Count of Ribagorza 1018–1035 with Mayor until 1032 | |

| New title | Emperor of Spain 1034–1035 |

Vacant Title next held by Ferdinand I of León |