San Esteban (1554 shipwreck)

San Esteban was a Spanish cargo ship that was wrecked in a storm in the Gulf of Mexico on what is now the Padre Island National Seashore in southern Texas on 29 April 1554.

San Esteban was a carrack, a common sailing vessel of the time. | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | San Esteban |

| Stricken: | 29 April 1554 |

| Fate: | Wrecked |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Carrack |

| Tons burthen: | 164 to 286 long tons (167 to 291 t) |

| Length: | 21 to 30 metres (69 to 98 ft) |

San Esteban was one of a flotilla of four ships carrying treasure from New Spain (Mexico) to Cuba. Three were wrecked in the storm, including San Esteban. Many of the three hundred sailors and passengers drowned while trying to reach shore. About thirty took a boat to seek help. Almost all the others died of thirst or starvation, or were killed by hostile local Karankawa Indians during their attempt to walk back to safety. The Spanish sent a salvage expedition, but recovered less than half of the cargo and treasure.

One of the wrecks was rediscovered in 1964. A private company, Platoro, Ltd., began to excavate the Espíritu Santo wreck in late 1967, which caused public outrage and the passage of new laws to protect wrecks on the Texan coast. The remains of San Esteban were found in 1970 and excavated in 1972–73. Many artifacts have been recovered and are held in the Corpus Christi Museum of Science and History. They include the world's oldest mariner's astrolabe with a confirmed date.

16th century

Outbound journey

San Esteban left Sanlúcar de Barrameda, Spain, on 4 November 1552. It was part of a fleet of 54 ships under the command of Captain-General Bartolomé Carreño that included an escort of six well-armed ships with 360 soldiers.[1] The escorting ships and 18 vessels were destined for the mainland of South America. Ten ships were heading to Santo Domingo and four to other parts of the West Indies. Sixteen were bound for San Juan de Ulúa (Veracruz) in New Spain (Mexico).[1]

The fleet had a difficult outbound voyage, suffering from bad weather, accidents and skirmishes with pirates. Eight vessels were lost and the rest scattered.[1] All the New Spain flotilla arrived safely at Vera Cruz during February and March 1553. The plan was to scrap eleven of the vessels and keep only five to make the return journey. This was typical. Ships from the Americas to Spain carried a much smaller volume of cargo than ships traveling in the other direction, although the shipments to Spain included valuable gold and silver.[1]

In September 1552 Vera Cruz had been battered by a hurricane. The harbor facilities had not yet been repaired. The ships were unloaded and refitted slowly, and only one was prepared to sail for Havana to join the fleet for the return journey to Spain that year.[1] The other four waited for over a year at Vera Cruz for the next fleet. These were the San Esteban, with Francisco del Huerto as master, Espíritu Santo, Santa María de Yciar and San Andrés with Antonio Corzo as master. Eventually the four decided not to wait longer and sailed for Havana without an escort. Antonio Corzo was named captain-general of the flotilla.[1]

Shipwreck

Oral tradition holds that a priest in Mexico predicted that there would be a disaster before the ships set sail, but that his warning was ignored.[2] The four ships left Vera Cruz on 9 April 1554, carrying over 400 people and valuable treasure and cargo. [3] The passengers included wealthy citizens, merchants and former soldiers,[4] but there were also a few prisoners and five Dominican missionaries who had decided to return to Spain.[5] The ships carried barrels holding over 85,000 pounds (39,000 kg) of silver coins and disks that had been minted in Mexico City.[6][7] The total cargo was worth more than two million pesos, the equivalent of almost US$10 million in 1975.[1]

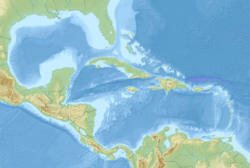

Due to prevailing winds and currents, the best route from Veracruz to Havana ran along the shore of what became Texas and Louisiana. The four vessels took this route.[8] On 29 April 1554 the ships were nearing Havana when they ran into a severe storm. Three of the ships were blown back to the west and wrecked on the Padre Island sandbars.[6] Only San Andrés escaped.[4][lower-alpha 1] Santa Maria de Yciar sank about 42 miles (68 km) north of the Rio Grande's mouth, where the Mansfield Channel is today.[9][lower-alpha 2] Espiritu Santo sank about 3 miles (4.8 km) to the north of this point and San Esteban was wrecked 2.5 miles (4.0 km) further north again.[9]

Survivors

There were about three hundred people on the wrecked vessels, of whom perhaps 100–150 escaped drowning.[1] Many women and children were among those who reached shore.[6] Francisco del Huerto, the master of San Esteban, was able to salvage a boat.[4] He made his way back to Vera Cruz with 30 men to get help.[10] The other survivors tried to walk south along the shore, not realizing that the nearest Spanish outpost was Tampico, 300 miles (480 km) away.[4] They met local people who seemed friendly and offered food, but later a fight broke out.[11] The Spanish escaped but the Karankawa Indians followed them, picking off stragglers with arrows. The Spanish made driftwood rafts to cross the Rio Grande. They lost their crossbows when the unstable rafts tipped.[6]

The Indians seized two men, took their clothes and then released them. The other Spaniards thought that perhaps the Indians only wanted their clothes, and stripped naked before going on. The women and children walked ahead to protect their modesty, and were ambushed and killed.[6] Almost all of the men died of thirst or starvation, or were killed.[11][4] There are records of only two who reached safety.[11] One, Brother Marcos de Mena, was left for dead after receiving multiple arrow wounds. He recovered and managed to reach Pánuco with the aid of friendly Indians.[4] The other, Francisco Vazquez, left the group early on and went back to the dunes facing the wrecks. He hid there until help arrived.[6] The event came to be called the "Wreck of the Three Hundred".[12]

Salvage

Francisco del Huerto managed to reach Vera Cruz and tell of the tragic event. A rescue mission was dispatched by sea under Ángel de Villafañe.[4] His small body of troops arrived in June. He guarded the site against looters from the Spanish settlements of Tampico and Pánuco until the salvage expedition arrived, and remained during the salvage operation from 23 July to 12 September.[11]

The main salvage crew dispatched from Vera Cruz to try to recover the treasure was under García de Escalante Alvarado (a nephew of Pedro de Alvarado). Alvarado bought six vessels to recover the Emperor Charles V's coin and bullion, and the other cargo.[4] There were 102 sailors, including eleven Spanish divers.[13] The masts of San Esteban could still be seen.[11] Salvage of San Esteban began at once. She had sunk in just 12 to 18 feet (3.7 to 5.5 m) of water, so could be thoroughly explored.[13] The salvage team dragged a chain along the bottom to find the two other ships.[11] Santa Maria de Yciar was located on 20 August. Her hull had split and the cargo was scattered around the wreck.[13]

Alvarado recovered over 29,000 pounds (13,000 kg) of silver as well as 22,000 pesos.[10][lower-alpha 3] The salvage crew also recovered personal items and cargo.[11] This included resin, cochineal, sugar, wood and hides.[4] The salvage crew found about 41% of the total value of the cargo.[1] 51,600 pounds (23,400 kg) of precious metals, coins, jewelry and religious artifacts were lost.[12] After that the island was rarely visited by Europeans for the next 200 years.[10]

20th century

Rediscovery and Espíritu Santo excavations

The 1554 wrecks were well documented and were shown on maps from 1646.[5] Treasure hunters who knew of them and beachcombers searching at random found traces of Spanish coins and fragments of ships on the Padre Island beaches throughout the 20th century.[9] The search intensified after dredgers accidentally destroyed Santa Maria de Yciar late in the 1950s.[6] In the summer of 1964 Vida Lee Connor found Espíritu Santo while scuba diving. She spent two years exploring her discovery before marking it with buoys and announcing the find. When she went back to the site later she found a private diving party taking items from the wreck. This was the start of a major debate about antiquities found in Texas.[9]

Platoro, Ltd., a private company, began to excavate Espíritu Santo wreck in late 1967. They found about 500 objects, including a gold bar, jewelry, and equipment used for navigation.[9] Platoro's exploration and retrieval of objects from the site started a long-running argument with the state of Texas about ownership of the artifacts. It also triggered the Texas legislature to pass the Antiquities Code in 1969 to prevent unauthorized excavation of future finds.[9]

In 1960, the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled that all territory up to 10.35 miles (16.66 km) from the Texas coastline was the property of the state of Texas. On this basis, due to a concern that the excavation should be conducted using scientific archaeological methods, and since this was the oldest shipwreck site to be examined in the Western Hemisphere, the state launched a suit against Platoro.[14] The Texas Archaeological Research Laboratory (TARL) at the University of Texas at Austin received the objects for study in the interim. There was a lengthy argument in the courts over state versus federal jurisdiction and compensation to Platoro.[14] The outcome was that Platoro was offered a cash settlement of $313,000. The state of Texas was acknowledged to be the custodian of the artifacts that had been recovered.[14]

The Antiquities Conservation Facility (ACF) was set up at TARL to study the material found by Platoro. The ACF extended principles and approaches developed by TARL to cover shipwreck conservation and analysis. This created the basis for future marine archaeology in Texas. After the ACF was closed these principles were carried forward in the Conservation Research Laboratory at Texas A&M University.[3][lower-alpha 4]

San Esteban excavation

In 1970, the Texas Antiquities Committee commissioned the Institute of Underwater Research to survey about 20 miles (32 km) of the coast over a one-month period. The institute found San Esteban during the survey.[9] Where the magnetometer indicated that iron was present, they used a "blower" to make a vertical jet of water that blew a 5 feet (1.5 m) layer of sand and shell away from the Pleistocene clay bottom and exposed the artifacts of the wreck.[8] The Antiquities Committee arranged for the site of the San Esteban to be excavated in the summer of 1972, with follow-up work in the summers of 1973 and 1975.[9] They focused on this wreck, since it had not been disturbed.[17]

Most of the ship's wooden hull was lost, but the layout of the ship could be seen from the placement of the anchors, guns and fasteners.[18] Corrosion and chemical interactions had melded many of the metal artifacts into conglomerates.[8] One of these weighed more than two tons and was more than 4 metres (13 ft) in length. It held two anchors, a hooped barrel gun of wrought-iron, and various other objects.[19] The divers made careful maps of the material they recovered, but had no way of determining on the spot what was inside the metal conglomerates encrusted by marine growth.[18] The divers recovered some of the conglomerates and some individual artifacts in 1972. The next year they recovered the rest of the large conglomerates, many smaller conglomerates and individual artifacts. In all they brought up 12,000 kilograms (26,000 lb) of artifacts in 1972–73.[8] The Texas Archaeological Research Laboratory received all the artifacts for analysis.[9]

Each encrusted conglomerate of concreted material was carefully documented with photographs, radiographs where practical, and detailed conservation records.[18] The researchers used hammers, chisels and small pneumatic chisels to break open the conglomerates.[20] They then subjected the metal and wood objects to complex and time-consuming processes to remove the products of corrosion and preserve them from future degradation.[15] There had been a suspicion that Platoro had excavated from the San Esteban as well as the Espíritu Santo, but the analysis of the San Esteban artifacts made it clear that the Platoro collection all came from Espíritu Santo.[15]

The San Esteban findings included three broken anchors and a wrought iron swivel gun that was also broken and unusable. The broken objects may have been kept so they could later be repaired, or may have just been used for ballast. There were four anchors in working condition.[18] The anchors were made of wrought iron.[8] Other finds included ship's fittings, tools and a cannon made by welding together iron bars.[8] This gun and the wrought iron guns were by now obsolete in Europe, but presumably considered sufficient for the New World.[21] The divers recovered the stern end of the keel and a portion of the sternpost.[8] The stern/keel section of the San Esteban is similar to other wrecks of the period, and contributes to a view of ship construction at the time.[22] Experts have estimated that the ship was 21 to 30 metres (69 to 98 ft) long and displaced 164 to 286 long tons (167 to 291 t).[1][23] The planks were 10 centimetres (3.9 in) thick.[23]

Miscellaneous finds included a brass buckle, shards of glass and olive pits. Several conglomerates held the exoskeletons of cockroaches, providing the first evidence of shipment of these insects between Europe and the Americas.[15] Personal possessions included a gold crucifix, pins, silver thimbles and silver reale coins.[4] The salvage team also found silver and gold bullion. Some locally-made items included prismatic obsidian blades and a polished nodule of iron pyrite for use as a mirror. [1]Other items included weapons and instruments for navigation. A mariner's astrolabe is the oldest such instrument with a confirmed date.[4] Pewter objects from England were found and stoneware from Cologne, Germany. In the end about 1,500 artifacts were retrieved from the San Esteban, 85% of them from the conglomerates.[21]

Preservation and display

On 21 January 1974, the National Park Service listed the three wrecks as the "Mansfield Cut Underwater Archeological District" in the National Register of Historic Places.[9] The Texas Antiquities Committee of the State of Texas owns the San Esteban wreck. It is managed by the National Park Service. The National Register lists the site as part of an archaeological district of national significance.[24]

The Texas Antiquities Committee sponsored a travelling exhibition of the finds from the 1554 wreck from 1977 to 1981, which visited 20 museums across Texas. The exhibition showed an anchor, cannons and the remaining parts of the keel and stern post. Display cases held explanatory text, illustrations and artifacts.[25] The recovered objects found a permanent home at the Corpus Christi Museum of Science and History. An extension to the museum opened in May 1990 to house the Shipwreck! exhibition.[25]

References

Notes

- Although San Andrés managed to reach Havana, she was so badly damaged that she was scrapped. Her cargo was taken to Spain by other ships.[1]

- Workers dredging the Mansfield Channel in the late 1950s accidentally destroyed the Santa Maria de Yciar site. Little is left but an anchor, now in the National Park Service collection, and a coin that was found on the beach.[9]

- The pesos were both gold and silver. A peso weighed about 1 ounce (28 g).[11]

- One principle when dealing with encrusted conglomerates of material is that archaeology must take precedence over conservation. Thus the conglomerates may be broken apart to determine what they contain.[15] But see Overview of conservation in archaeology; basic archaeological conservation procedures from the Conservation Research Laboratory for a discussion of the importance of preserving artifacts and recording their context wherever possible.[16]

Citations

- Arnold & Wickman 2010.

- Francaviglia 1998, p. 18.

- Catsambis, Ford & Hamilton 2011, p. 287.

- Drolet & Stryker 2014.

- Williams 2010, p. 103.

- The 1554 Wrecks: Travel South Texas.

- Williams 2010, p. 104.

- Cordell et al. 2008, p. 245.

- Cultural Resource Issues: NPS.

- Padre Island National Seashore:NPS.

- Padre Island – The Spanish: NPS.

- Venable 2011, p. 243.

- Williams 2010, p. 105.

- Venable 2011, p. 244.

- Catsambis, Ford & Hamilton 2011, p. 290.

- Hamilton 1999, pp. 4ff.

- Williams 2010, p. 106.

- Catsambis, Ford & Hamilton 2011, p. 288.

- Williamson & Nickens 2000, p. 196.

- Catsambis, Ford & Hamilton 2011, p. 289.

- Muckelroy 1978, p. 113.

- Hocker & Ward 2004, p. 132.

- Castro 2005, p. 132.

- Shipwrecks in the National Register of Historic Places: NPS.

- Babits & Van Tilburg 1998, p. 558.

Sources

- Arnold, J. Barto III; Wickman, Melinda Arceneaux (15 June 2010). "Handbook of Texas Online". Padre Island Spanish Shipwrecks of 1554. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 9 February 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Babits, Lawrence E.; Van Tilburg, Hans (31 January 1998). Maritime Archaeology: A Reader of Substantive and Theoretical Contributions. Springer. ISBN 978-0-306-45330-4. Retrieved 9 February 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Castro, Filipe Vieira de (2005). The Pepper Wreck: A Portuguese Indiaman at the Mouth of the Tagus River. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-60344-599-3. Retrieved 9 February 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Catsambis, Alexis; Ford, Ben; Hamilton, Donny L. (8 September 2011). The Oxford Handbook of Maritime Archaeology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537517-6. Retrieved 12 February 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cordell, Linda S.; Lightfoot, Kent; McManamon, Francis; Milner, George (30 December 2008). Archaeology in America: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-02189-3. Retrieved 9 February 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Padre Island Administrative History". Cultural Resource Issues. National Park Service. 14 June 2005. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- Drolet, Robert; Stryker, Rick (2014). "Spanish Shipwrecks in 1554: "The Wreck of the 300"". Corpus Christi Museum of Science and History. Retrieved 9 February 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Francaviglia, Richard V. (1998). From Sail to Steam: Four Centuries of Texas Maritime History, 1500–1900. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-72503-4. Retrieved 12 February 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hamilton, Donny L. (1 January 1999). "Methods for Conserving Archaeological Material from Underwater Sites" (PDF). Chapter: Overview of conservation in archaeology; basic archaeological conservation procedures. Texas A&M University. Retrieved 12 February 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hocker, Frederick M.; Ward, Cheryl A. (2004). The Philosophy of Shipbuilding: Conceptual Approaches to the Study of Wooden Ships. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-313-0. Retrieved 12 February 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Muckelroy, Keith (1978). Maritime Archaeology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29348-8. Retrieved 12 February 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Padre Island National Seashore". National Park Service. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- "Padre Island – The Spanish". National Park Service. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- "Abandoned Shipwreck Act Guidelines". Shipwrecks in the National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- "The 1554 Wrecks". Travel South Texas. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- Venable, Shannon L. (2011). Gold: A Cultural Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-38430-1. Retrieved 9 February 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Williams, C. Herndon (2010). Texas Gulf Coast Stories. The History Press. ISBN 978-1-60949-032-4. Retrieved 12 February 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Williamson, Ray A.; Nickens, Paul R. (2000). Science and Technology in Historic Preservation. Springer. ISBN 978-0-306-46212-2. Retrieved 12 February 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)