Saiō

A Saiō (斎王), also known as Itsuki no Miko (斎皇女), was an unmarried female member of the Japanese Imperial Family, sent to Ise to serve at Ise Grand Shrine from the late 7th century until the 14th century. The Saiō's residence, Saikū (斎宮), was about 10 km north-west of the shrine. The remains of Saikū are situated in the town of Meiwa, Mie Prefecture, Japan.[1]

Origins

According to Japanese legend, around 2,000 years ago the divine Yamatohime-no-mikoto, daughter of the Emperor Suinin, set out from Mt. Miwa in Nara Prefecture in search of a permanent location to worship the goddess Amaterasu-omikami.[2] Her search lasted for 20 years and eventually brought her to Ise, Mie Prefecture, where the Ise Shrine now stands.[3] Prior to Yamatohime-no-mikoto's journey, Amaterasu-omikami had been worshiped at the Imperial Palaces in Yamato.

According to the Man'yōshū (The Anthology of Ten Thousand Leaves), the first Saiō to serve at Ise was Princess Ōku, daughter of Emperor Tenmu, during the Asuka period of Japanese history. Mention of the Saiō is also made in the Aoi, Sakaki and Yugao chapters of The Tale of Genji, as well as in the 69th chapter of The Tales of Ise (Ise Monogatari).

In the 13th century, Jien recorded in the Gukanshō that during the reign of Emperor Suinin, the first High Priestess (saigū) was appointed for Ise Shrine.[4] Hayashi Gahō's 17th century Nihon Ōdai Ichiran is somewhat more expansive, explaining that since Suinin's time, a daughter of the emperor was almost always appointed as high priestess, but across the centuries, there have been times when the emperor himself had no daughter; and in such circumstances, the daughter of a close relative of the emperor would have been appointed to fill the untimely vacancy.[5]

Role

The role of the Saiō was to serve as High Priestess at Ise Shrine on behalf of the Emperor, to represent the role first set out by Yamatohime-no-mikoto. Three rituals a year were conducted at the Shrine in which the Saiō prayed for peace and protection. In June and November each year, she journeyed to the Shrine to perform the Tsukinamisai Festival. In September in ancient Calendar, she performed the Kannamesai Festival 神嘗祭 to make offerings to the kami of the year's new grain harvest.[6]

For the rest of the year, the Saiō lived in Saikū, a small town of up to 500 people approximately 10 kilometers north-west of Ise, in modern Meiwa, Mie Prefecture. Life at Saikū was, for the most part, peaceful. The Saiō would spend her time composing waka verses, collect shells on the shore of Ōyodo beach, or set out in boats and recite poetry upon the water and wait to be recalled to Kyoto.[6]

Selection process

When a former Emperor died or abdicated the throne, when the old Saiō's relative died, or when certain political power required, she would be recalled to the capital and a new Saiō selected from one of the new Emperor's unmarried female relatives using divination by either burnt tortoise shell or deer bones. The new Saiō would then undergo a period of purification before setting out with her retinue of up to 500 people for Saikū, never to return to the capital until recalled by the next Emperor.

Upon the selection of the new Saiō, the current Saiō and her retinue would return to the capital to resume their lives as part of the Imperial Court. Often a Saiō was quite young when she left the capital for Saikū, and would only be in her mid-teens or early twenties when she returned to the capital. It was considered a great honor to marry a former Saiō and her time at Saikū improved her own position at court and those of the people who served with her.

Procession to Saikū

The below is the explanation of the procession routes of the Saiō after the capital was moved to Heian-kyō in 794.

The procession began in what is today the Arashiyama district on the west side of Kyoto. In the Heian period, successive imperial princesses stayed in the Nonomiya Shrine for a year or more to purify themselves before becoming representatives of the imperial family at the Ise Shrine.[7] Contemporary annual processions recreate a scene from a picture scroll of the imperial court during the Heian period, starting from the shrine and continuing as far as the Togetsu-kyo Bridge, Arashiyama.[8]

The procession of the Saiō from Kyoto to Saikū, the Saiō's official residence in Ise, was the largest procession of its kind in Japan for its time. Up to 500 people would set out from Kyoto as a part of the Saiō's retinue for the six-day-and-five-night journey. From Kyoto, they travelled in an eastward direction, passing through the Suzuka Pass, which was without doubt the most difficult part of the journey. Once clearing the pass, the retinue would descend into the Ise region and turn south, eventually reaching the Kushida River (櫛田川). Here, the Saiō would stop to perform a final cleansing ritual before crossing the river and travelling the short distance to Saikū.[9]

The Saiō was expected to remain at Saikū until the emperor whom she represented either died or abdicated the throne. The Saiō was permitted to return to Kyoto only on the provision of a close relative's death. When returning to Kyoto, a different route was taken through the mountains to Nara, then to Osaka Bay where a ceremony was to be performed before she could finally return to the capital.

Saiōs from Japanese literature

Princess Ōku

The Man'yōshū (The Anthology of Ten Thousand Leaves), tells the story of Princess Ōku, the first Saiō to serve at Ise Shrine. The daughter of Emperor Tenmu, Japan's 40th emperor (according to the traditional order of succession), Princess Ōku and her younger brother, Prince Ōtsu, survived the Jinshin incident. After taking up her role as Saiō, her brother was put to death for treason in 686 and Princess Ōku was relieved of her duties and returned to Yamato. Here she enshrined her brother's remains on Mt. Futakami before an end was put to her life at the age of 41.[10]

Princess Yoshiko

The Tale of Genji tells the story of Rokujo-no-miyasudokoro, which is believed to be based on Princess Yoshiko, who served as Saiō from 936 to 945. In The Tale of Genji, Rokujo-no-miyasudokoro became the Saiō of Ise Shrine at the young age of 8, serving at the shrine for 9 years. After returning to the capital, she became a consort to Emperor Murakami and gave birth to Princess Noriko. She became famous throughout Kyoto for her colorful life, devoting herself to waka poetry and music. According to the story, she falls in love with Prince Genji, but her jealous nature brings about the death of two of her rivals. When her daughter is chosen as Saiō at the age of 13, Rokujo-no-miyasudokoro decides to join her in Saikū to help her overcome her feelings for Genji.[10]

Princess Yasuko

The love story of Ariwara-no-Narihira and the 31st Saiō, Princess Yasuko (served as Saiō from 859 to 876), is told in the 69th chapter of The Tales of Ise. Ariwara-no-Narihira, well known in his time for his good looks, is married to Princess Yasuko's cousin, but on meeting at the Saikū, they fall into forbidden love. Giving in to temptation, they secretly meet under a pine tree on the shore of Ōyodo Port to reveal their feelings for one another and to promise to meet again the following night. But this first secret meeting would also be the last, as Narihira was due to depart that next day for Owari Province. Princess Yasuko came to see Narihira off, and they were never to see each other again, though it is said that Princess Yasuko bore a child as a result of the brief love affair.[11]

End of the Saiō system

It is not precisely clear when the Saiō system ended, but what is known is that it occurred during the turmoil of the Nanboku-chō Period when two rival Imperial courts were in existence, in Kyoto and Yoshino. The Saiō system had been in steady decline up to this period, with Saikū reverting to just another rural rice farming village after the system's collapse.

Though the area of Saikū remained, it was unclear exactly where the old Imperial town stood until pottery remains were unearthed in 1970 during the construction of housing in the Saikū area, Meiwa Town. A modern museum was built on the site of the first finds and archaeological excavations are continuing, held each summer with the aid of volunteer school children from all over Japan. Though a site for the main Saiō residence has been discovered, a large percentage of it lies beneath the main Kintetsu Ise railway line and is inaccessible. Itsukinomiya Historical Experience Hall, a reconstruction of the building using traditional techniques, was built in the 1990s and stands beside Saiku station on the local Kintetsu rail line, no more than 200 metres for the original site.

Festivals

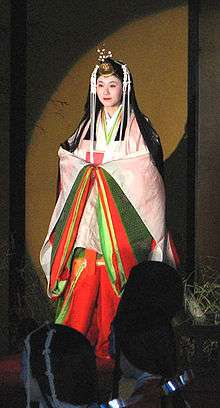

The Aoi Matsuri, the first of the three main festivals held in Kyoto each year, re-enacts the Heian period march of the Saiō to the Shimigamo Shrine (Lower Kamo Shrine) in Sakyo Ward. This festival is held every year on May 15 and in 2006 consisted of 511 people dressed in traditional Heian court clothing and 40 cows and horses, stretching around 800 meters from start to finish. This festival is said to have started in the 6th century when the Emperor sent his representatives to Shimogamo and Kamigamo Shines to pray from good harvests.

The Saiō Matsuri is held in the town of Meiwa, Mie Prefecture, on the first weekend of June each year. First held in 1983, it re-enacts the march of the Saiō from her residence at Saikū, to the nearby Ise Shrine. More than 100 people dressed in traditional Heian period costume march along a section of the old Ise Kaido (pilgrimage road), before ending in the grounds of the Saikū Museum.

List of Saiō

After the establishment of the Saiō system by Emperor Tenmu, these were priestesses of Ise Shrine.

| Saiō[12] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Saiō | Japanese Name | Birth / Death year | Appointed by | Relationship to Emperor | |

| 673–686 | Princess Ōku | 大来皇女 | 661–701 | Emperor Tenmu | Daughter | |

| 698–701 | Princess Taki | 多紀皇女 | ?–751 | Emperor Monmu | Aunt | |

| 701–706? | Princess Izumi | 泉内親王 | ?–734 | Emperor Monmu | Distant Relative | |

| 706–707? | Princess Takata | 田形内親王 | ?–728 | Emperor Monmu | Aunt | |

| 715?–721 | Princess Kuse | 久勢女王 | Empress Genshō | Unknown | ||

| 721–730? | Princess Inoe | 井上内親王 | 717–775 | Emperor Shōmu | Daughter | |

| 744?–749 | Princess Agata | 県女王 | Emperor Shōmu | Unknown | ||

| 749–756? | Princess Oyake | 小宅女王 | Empress Kōken | Distant Relative | ||

| 758–764? | Princess Yamao | 山於女王 | Emperor Junnin | Unknown | ||

| 772–775? | Princess Sakahito | 酒人内親王 | 754–829 | Emperor Kōnin | Daughter | |

| 775?–781? | Princess Kiyoniwa | 浄庭女王 | Emperor Kōnin | Distant Relative | ||

| 782–796 | Princess Asahara | 朝原内親王 | 779–817 | Emperor Kanmu | Daughter | |

| 796–806 | Princess Fuse | 布勢内親王 | ?–812 | Emperor Kanmu | Daughter | |

| 806–809 | Princess Ōhara | 大原内親王 | ?–863 | Emperor Heizei | Daughter | |

| 809–823 | Princess Yoshiko | 仁子内親王 | ?–889 | Emperor Saga | Daughter | |

| 823–827 | Princess Ujiko | 氏子内親王 | ?–885 | Emperor Junna | Daughter | |

| 828–833 | Princess Yoshiko | 宜子女王 | Emperor Junna | Niece | ||

| 833–850 | Princess Hisako | 久子内親王 | ?–876 | Emperor Ninmyō | Daughter | |

| 850–858 | Princess Yasuko | 晏子内親王 | ?–900 | Emperor Montoku | Daughter | |

| 859–876 | Princess Yasuko | 恬子内親王 | ?–913 | Emperor Seiwa | Sister (different mother) | |

| 877–880 | Princess Satoko | 識子内親王 | 874–906 | Emperor Yōzei | Sister (different mother) | |

| 882–884 | Princess Nagako | 掲子内親王 | ?–914 | Emperor Yōzei | Aunt | |

| 884–887 | Princess Shigeko | 繁子内親王 | ?–916 | Emperor Kōkō | Daughter | |

| 889–897 | Princess Motoko | 元子女王 | Emperor Uda | Distant Relative | ||

| 897–930 | Princess Yasuko | 柔子内親王 | ?–959 | Emperor Daigo | Sister (same mother) | |

| 931–936 | Princess Masako | 雅子内親王 | 909–954 | Emperor Suzaku | Sister (different mother) | |

| 936 | Princess Sayoko | 斉子内親王 | 921–936 | Emperor Suzaku | Sister (different mother) | |

| 936–945 | Princess Yoshiko | 徽子女王 | 929–985 | Emperor Suzaku | Niece | |

| 946 | Princess Hanako | 英子内親王 | 921–946 | Emperor Murakami | Sister (different mother) | |

| 947–954 | Princess Yoshiko | 悦子女王 | Emperor Murakami | Niece | ||

| 955–967 | Princess Rakushi | 楽子内親王 | 952–998 | Emperor Murakami | Daughter | |

| 968–969 | Princess Sukeko | 輔子内親王 | 953-992 | Emperor Murakami | Daughter | |

| 969–974 | Princess Takako | 隆子女王 | ?–974 | Prince Akiakira | Daughter | |

| 975–984 | Princess Noriko | 規子内親王 | 949–986 | Emperor Murakami | Daughter | |

| 984–986 | Princess Saishi | 済子女王 | Prince Akiakira | Daughter | ||

| 986–1010 | Princess Kyōshi | 恭子女王 | 984–? | Prince Tamehira | Daughter | |

| 1012–1016 | Princess Masako | 当子内親王 | 1001–1023 | Emperor Sanjō | Daughter | |

| 1016–1036 | Princess Senshi | 嫥子女王 | 1005–1074 | Prince Tomohira | Daughter | |

| 1036–1045 | Princess Nagako | 良子内親王 | 1029–1077 | Emperor Go-Suzaku | Daughter | |

| 1046–1051 | Princess Yoshiko | 嘉子内親王 | c.1030–? | Emperor Go-Reizei | ||

| 1051–1068 | Princess Tagako | 敬子女王 | Emperor Go-Reizei | |||

| 1069–1072 | Princess Toshiko | 俊子内親王 | 1056–1132 | Emperor Go-Sanjō | ||

| 1073–1077 | Princess Atsuko | 淳子女王 | Emperor Shirakawa | |||

| 1078–1084 | Princess Yasuko | 媞子内親王 | 1076–1096 | Emperor Shirakawa | ||

| 1087–1107 | Princess Yoshiko | 善子内親王 | 1077–1132 | Emperor Horikawa | ||

| 1108–1123 | Princess Aiko | 恂子内親王 | 1093–1132 | Emperor Toba | ||

| 1123–1141 | Princess Moriko | 守子女王 | 1111–1156 | Emperor Sutoku | ||

| 1142–1150 | Princess Yoshiko | 妍子内親王 | ?-1161 | Emperor Konoe | ||

| 1151–1155 | Princess Yoshiko | 喜子内親王 | Emperor Konoe | |||

| 1156–1158 | Princess Asako | 亮子内親王 | 1147–1216 | Emperor Go-Shirakawa | ||

| 1158–1165 | Princess Yoshiko | 好子内親王 | 1148–1192 | Emperor Nijō | ||

| 1165–1168 | Princess Nobuko | 休子内親王 | 1157–1171 | Emperor Rokujō | ||

| 1168–1172 | Princess Atsuko | 惇子内親王 | 1158–1172 | Emperor Takakura | ||

| 1177–1179 | Princess Isako | 功子内親王 | 1176-? | Emperor Takakura | ||

| 1185–1198 | Princess Sayoko | 潔子内親王 | 1179-after 1227 | Emperor Go-Toba | ||

| 1199–1210 | Princess Sumiko | 粛子内親王 | 1196-? | Emperor Tsuchimikado | ||

| 1215–1221 | Princess Hiroko | 熙子内親王 | 1205-? | Emperor Juntoku | ||

| 1226–1232 | Princess Toshiko | 利子内親王 | 1197–1251 | Emperor Go-Horikawa | ||

| 1237–1242 | Princess Teruko | 昱子内親王 | 1231–1246 | Emperor Shijō | ||

| 1244–1246 | Princess Akiko | 曦子内親王 | 1224–1262 | Emperor Go-Saga | ||

| 1262–1272 | Princess Yasuko | 愷子内親王 | 1249–1284 | Emperor Kameyama | ||

| 1306–1308 | Princess Masako | 弉子内親王 | 1286–1348 | Emperor Go-Nijō | ||

| 1330–1331 | Princess Yoshiko | 懽子内親王 | 1315–1362 | Emperor Go-Daigo | ||

| 1333-1334 | Princess Sachiko | 祥子内親王 | Emperor Go-Daigo | |||

Notes

- http://www.bunka.pref.mie.lg.jp/saiku/p0048200012.htm

- Brown Delmer et al. (1979). Gukanshō, p. 253; Varley, H. Paul. (1980). Jinnō Shōtōki, pp. 95-96; Titsingh, Isaac. (1834). Annales des empereurs du japon, p. 10.

- The Deep Purple Story of Meiwa (紫紺の語り部) (Meiwa Town Office, 2003), p. 3.

- Brown, p. 253.

- Titsingh, p. 10.

- The Deep Purple Story of Meiwa, p. 9.

- Kyoto City Tourism and Culture Information Site: Nonomiya Shrine. Archived 2007-06-26 at Archive.today

- Kyoto City: Saigū Procession; Events, October 2006.

- Saiō Procession (Documentary movie, Saikū Historical Museum).

- The Deep Purple Story of Meiwa, p. 6.

- The Deep Purple Story of Meiwa, p. 5.

- Saikū Historical Museum, Meiwa, Mie: wall-display information table

References

- Brown, Delmer and Ichiro Ishida, eds. (1979). [ Jien, c.1220], Gukanshō; "The Future and the Past: a translation and study of the 'Gukanshō,' an interpretive history of Japan written in 1219" translated from the Japanese and edited by Delmer M. Brown & Ichirō Ishida. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03460-0

- Farris, William Wayne. (1999). "Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan," Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 54, No. 1, pp. 123–126.

- Titsingh, Isaac. (1834). [Siyun-sai Rin-siyo/Hayashi Gahō, 1652]. Nipon o daï itsi ran; ou, Annales des empereurs du Japon. Paris: Oriental Translation Society of Great Britain and Ireland.

- Varley, H. Paul , ed. (1980). [ Kitabatake Chikafusa, 1359], Jinnō Shōtōki ("A Chronicle of Gods and Sovereigns: Jinnō Shōtōki of Kitabatake Chikafusa" translated by H. Paul Varley). New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-04940-4

See also

- Saiin, the high priestess of the Kamo Shrine

- Kikoe-ōgimi, the high priestess of Ryukyu Kingdom

External links

![]()