Vajroli mudra

Vajroli mudra (Sanskrit: वज्रोली मुद्रा vajrolī mudrā), the Vajroli Seal, is a practice in Hatha yoga which requires the yogin to preserve his semen, either by learning not to release it, or if released by drawing it up through his urethra from the vagina of "a woman devoted to the practice of yoga".[1]

The mudra was described as "obscene"[2] by the translator Rai Bahadur Srisa Chandra Vasu, and as "obscure and repugnant"[2] by another translator, Hans-Ulrich Rieker.[2]

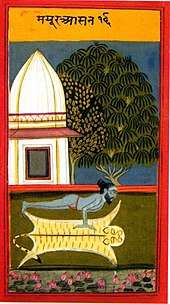

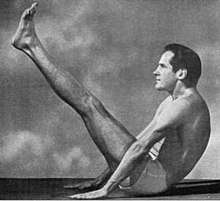

The mudra is rarely practised in modern times. It was covered in the 1900s by the American sexologist Ida C. Craddock, leading to her imprisonment and suicide. The explorer Theos Bernard learnt and illustrated the posture associated with the mudra. The pioneer of modern yoga, Krishnamacharya, gives impractical instructions for the mudra, demonstrating in Norman Sjoman's opinion that he had never tried the practice.

Context

Hatha yoga is a branch of yoga that developed around the 11th century. Like earlier forms such as Patanjali's yoga, its ultimate goal was liberation, moksha, and its methods included meditation. It added a set of physical methods contributing to liberation including purification techniques (satkarmas), non-seated postures (asanas), elaborate breath-control (pranayama), and physical techniques to manipulate vital energy, the mudras.[3][4]

Mudras are gestures of the body, used in hatha yoga to assist in the spiritual journey towards liberation. Mudras such as Khechari Mudra and Mula Bandha are used to seal in the vital energy, which can take various forms such as prana (related to the breath) and bindu (related to the semen). The classical sources for the mudras in yoga are two medieval texts, the Gheranda Samhita and the Hatha Yoga Pradipika.[5] However, many hatha yoga texts describe mudras.[6]

The Hatha Yoga Pradipika 3.5 states the importance of mudras in yoga practice:

Therefore the [Kundalini] goddess sleeping at the entrance of Brahma's door [at the base of the spine] should be constantly aroused with all effort, by performing mudra thoroughly.

— HYP 3.5

In the 20th and 21st centuries, the yoga teacher Satyananda Saraswati, founder of the Bihar School of Yoga, continued to emphasize the importance of mudras in his instructional text Asana, Pranayama, Mudrā, Bandha.[5]

Mudra

Vajroli mudra, the Vajroli Seal, differs from other mudras in that it does not consist of sealing in a vital fluid physically, but involves its recovery. The mudra requires the yogin to preserve his semen, either by learning not to release it, or if released by drawing it up through his urethra from the vagina of "a woman devoted to the practice of yoga".[1] It is described in the Hatha Yoga Pradipika 3.82–89.[7]

The Shiva Samhita 4.78–104 calls Vajroli mudra "the secret of all secrets" and claims that it enables "even a householder" (a married man, not a yogic renunciate) to be liberated. It calls for the man to draw up the rajas, the woman's sexual fluid, from her vagina. It explains that the loss of bindu, the vital force of the semen, causes death, while its retention causes life. The god Shiva says "I am bindu, the goddess (Shakti) is rajas."[8]

The Shiva Samhita states in the same passage that Sahajoli and Amaroli are variations of the mudra. The yogin is instructed to practice by using his wind to hold back the urine while he is urinating, and then to release it little by little. After six months' practice he will in this way become able to hold back his bindu, "even if he enjoys a hundred women".[8]

Reception

Modern description

Vajroli mudra is not often described in modern accounts, still less actually practised. The earliest Westerner to write about it was the American yoga scholar and sexologist Ida C. Craddock. Opposing the predominant religious culture of her nation at the time, fundamentalist Protestant Christianity, Craddock was struck by the Shiva Samhita's account of Vajroli mudra, with "the idea that sexual union could facilitate divine realization". She took the Hindu tantra concept that the male body was able to transform the sucked-up sexual fluids into an immortal "diamond body",[9] and reworked it into a system involving delayed ejaculation to increase sexual pleasure within marriage.Further, she asserted that God was the third partner in such a marriage, "in what amounted to a sacred menage-a-trois."[9] Craddock's emphasis on yoga and her new "mystico-erotic religion" enraged the authorities; she was tried in New York for obscenity and blasphemy, and imprisoned for three months. Facing federal charges on her release, she killed herself. The yoga scholar Andrea Jain notes that Craddock's "sacralization of sexual intercourse"[9] is far from radical by modern standards, but it was "antisocial heterodoxy" in the 1900s, leading indeed to her "martyrdom".[9]

The explorer and author Theos Bernard illustrates himself in a posture named Vajroli mudra in his 1943 participant observer book Hatha Yoga: The Report of a Personal Experience. The posture, somewhat resembling Navasana, is seated, the legs raised to about 45 degrees and held out straight, the body leaning back and the back rounded so that the palms can be placed on the ground below the raised thighs, the arms held straight.[10] Bernard states that he was instructed to learn this once he could do lotus position (Padmasana) so that he would be strong enough to use it "in the more advanced stages" of his hatha yoga training; there is no suggestion in the book that he followed the full practice.[11]

The yoga scholar-practitioner Norman Sjoman criticises Krishnamacharya, otherwise known as the father of modern yoga, for including "material on yogic practices from these academic sources in his text without knowing an actual tradition of teaching connected with the practice."[12] Sjoman explains that Krishnamacharya recommended for Vajroli mudra "a glass rod to be inserted into the urethra an inch at a time."[12] In Sjoman's view, this showed "that he has most certainly not experimented with this himself in the manner he recommends."[12]

The magazine of Satyananda Saraswati's Bihar School of Yoga, noting the criticism of Vajroli mudra, defends the practice in a 1985 article. It states that the Shatkarma Sangraha describes seven Vajroli practices, starting with "the simple contraction of the uro-genital muscles and later the sucking up of liquids".[13] It adds that only when the first six practices are completed can the last, "yogic intercourse",[13] succeed. It notes also that sexual climax is the one moment in ordinary lives when "the mind becomes completely void of its own accord",[13] but the moment is brief as the lowest chakras (energy centres in the subtle body) are involved. Withholding the semen allows the energy to awaken kundalini, the energy supposedly coiled at the base of the spine, instead.[13]

Colin Hall and Sarah Garden, writing in Yoga International, note that, as with "yogic practices" like Khechari mudra, Mula bandha, and the various shatkarmas such as Dhauti (cleaning the gastro-intestinal tract by swallowing and pulling out lengths of cloth), Vajroli mudra is "rarely practiced by anyone at all." They state that the question is not whether these practices are right or wrong, but whether they are appropriate in a modern context.[14]

Modern omission

The lack of discussion of Vajroli mudra is related to the more general historic denigration of hatha yoga as unscientific and dangerous. The translator Rai Bahadur Srisa Chandra Vasu translated texts such as the Gheranda Samhita and the Shiva Samhita, starting in 1884, giving "stern warnings against the inherent perils of engaging in these practices".[2] Vasu intentionally omitted Vajroli mudra from his translations, describing it as "an obscene practice indulged in by low class Tantrists".[2][15] The yoga scholar Mark Singleton noted in 2010 that "the practice of vajroli has continued to be censored in modern editions of hatha yoga texts", giving as example Vishnudevananda's omission of it from his Hatha Yoga Pradipika with the explanation that "it falls outside the bounds of wholesome practice", "sattvic sadhana",[2] along with sahajoli and amaroli. Similarly, Singleton notes, Hans-Ulrich Rieker calls these three practices "obscure and repugnant"[16] and omits them from his 1957 translation of the Hatha Yoga Pradipika.[2]

References

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 242, 250-252.

- Singleton 2010, pp. 44–47.

- Mallinson 2011, pp. 770–781.

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. xx-xxi.

- Saraswati, Satyananda (1997). Asana Pranayama Mudrā Bandha. Bihar Yoga Bharti. p. 422. ISBN 81-86336-04-4.

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 228-258.

- Hatha Yoga Pradipika 3.82–89.

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 250-252.

- Jain 2015, pp. 22-25.

- Bernard 2007, p. 127, plate XXVI.

- Bernard 2007, pp. 28–29.

- Sjoman 1999, p. 66.

- "Vajroli Mudra (The Thunderbolt Attitude)". Bihar School of Yoga. 1985. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- Hall, Colin; Garden, Sarah (n.d.). "Lost in Translation: Is Mulabandha Relevant for Modern Yogis?". Yoga International. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- Vasu, S. C. (1915). The Yoga Sastra, Consisting of an Introduction to Yoga Philosophy, Sanskrit Text with English Translation of 1 The Siva Samhita and of 2 The Gheranda Samhita. Bahadurganj: Suhindra Nath Vasu. p. 51.

- Rieker, Hans-Ulrich (1989) [1957]. The Yoga of Light: Hatha Yoga Pradipika. Unwin. p. 127.

Sources

- Bernard, Theos (2007). Hatha Yoga: The Report of a Personal Experience. Harmony. ISBN 978-0-9552412-2-2. OCLC 230987898.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jain, Andrea (2015). Selling Yoga : from Counterculture to Pop culture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-939024-3. OCLC 878953765.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mallinson, James (2011). Knut A. Jacobsen; et al. (eds.). Haṭha Yoga in the Brill Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 3. Brill Academic. pp. 770–781. ISBN 978-90-04-27128-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mallinson, James; Singleton, Mark (2017). Roots of Yoga. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-241-25304-5. OCLC 928480104.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Singleton, Mark (2010). Yoga Body : the origins of modern posture practice. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539534-1. OCLC 318191988.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sjoman, Norman E. (1999) [1996]. The Yoga Tradition of the Mysore Palace (2nd ed.). Abhinav Publications. ISBN 81-7017-389-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)