Safiye Sultan (wife of Murad III)

Safiye Sultan (Ottoman Turkish: صفیه سلطان; c. 1550 – 1619[lower-alpha 1]) was the Albanian concubine of Murad III and Valide Sultan of the Ottoman Empire as the mother of Mehmed III and the grandmother of Sultans: Ahmed I and Mustafa I. Safiye was also one of the eminent figures during the era known as the Sultanate of Women. She lived in the Ottoman Empire as a courtier during the reigns of seven sultans: Suleiman the Magnificent, Selim II, Murad III, Mehmed III, Ahmed I, Mustafa I, and Osman II.

| Safiye Sultan | |

|---|---|

The türbe of Safiye is located next to that of Murad III in the courtyard of Hagia Sophia | |

| Valide Sultan of the Ottoman Empire | |

| Tenure | 15 January 1595 – 22 December 1603 |

| Predecessor | Nurbanu Sultan |

| Successor | Handan Sultan |

| Haseki Sultan of the Ottoman Empire (Imperial Consort) | |

| Tenure | c. 1575 – 15 January 1595 |

| Predecessor | Nurbanu Sultan |

| Successor | Kösem Sultan |

| Born | c. 1550 Dukagjin highlands, (Albania) |

| Died | c. 1619 (aged 68–69) Eski Palace, Bayezit Square, Istanbul, Ottoman Empire |

| Burial | Mausoleum of Murad III, Hagia Sophia Mosque, Istanbul |

| Spouse | Murad III |

| Issue | Mehmed III Şehzade Mahmud Ayşe Sultan Fatma Sultan |

| Religion | Islam, previously Roman Catholic |

Background

The identity of Safiye has often been confused with that of her Venetian mother-in-law, Nurbanu, leading some to believe that Safiye was also of Venetian descent.[2] However, Safiye was of Albanian origin, born in the Dukagjin highlands.[3]

In 1563, at the age of 13, she was presented as a slave to the future Murad III by Mihrimah Sultan, daughter of Suleiman the Magnificent and Hurrem Sultan.[4] Given the name Safiye ("the pure one"), she became a concubine of Murad (then the eldest son of Sultan Selim II). On 26 May 1566, she gave birth to Murad's son, the future Mehmed III, the same year Suleiman the Magnificent died.

Haseki Sultan

Safiye had been Murad's only concubine before his accession, and he continued having a monogamous relationship with her for several years into his sultanate. His mother Nurbanu advised him to take other concubines for the good of the dynasty,[5] which by 1581 had only one surviving heir, Murad and Safiye's son Mehmed. In 1583, Nurbanu accused Safiye of using witches and sorcerers to render Murad impotent and prevent him from taking new concubines. This resulted in the imprisonment and torture of Safiye's servants.[6] Murad's sister Esmehan presented him with two beautiful concubines, which he accepted. Cured of his impotence, he went on to father twenty sons and twenty-seven daughters.[7]

Venetian reports state that after an initial bitterness, Safiye kept her dignity and showed no jealousy of Murad's concubines. She even procured more for him, earning the gratitude of the Sultan, who continued to value her and consult her on political matters, especially after the death of Nurbanu. During Murad's latter years, Safiye returned to being his only companion.[7] However, it is unlikely that Safiye ever became Murad's wife—though the Ottoman historian Mustafa Ali refers to her as such, he is contradicted by reports from the Venetian and English ambassadors.[7]

She was influential as a Haseki, a rank bestowed on her less than a year after Murad ascended the throne.[8] As Giovanni Moro reported in 1590 with the authority she {Safiye} enjoys as mother of the prince, she intervenes on occasion in affairs of state, although she is much respected in this, and is listened to by His Majesty who considers her sensible and wise.

- Issue

Together with Murad, Safiye had four children:

- Mehmed III (May 26, 1566 – December 22, 1603), became the next sultan succeeding his father Murad III;

- Şehzade Mahmud (1568, Manisa Palace, Manisa – 1581, Topkapı Palace, Istanbul, buried in Selim II Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Ayşe Sultan (died 15 May 1605, buried in Mehmed III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque), married firstly on 20 May 1586 Damat Ibrahim Pasha, married secondly on 5 April 1602 to Damat Yemişçi Hasan Pasha, married thirdly on 29 June 1604 to Damat Güzelce Mahmud Pasha;

- Fatma Sultan (buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque), married on 6 December 1593 to Damat Halil Pasha, married secondly in December 1604 to Hızır Pasha.

Valide Sultan and regent

When Murad died in 1595, Safiye arranged for her son Mehmed to succeed as a sultan, and she became the Valide Sultan—one of the most powerful in Ottoman history. Until her son's death in 1603, Ottoman politics were determined by a party headed by herself and Gazanfer Ağa, chief of the white eunuchs and head of the enderun (the imperial inner palace).[9]

Safiye eventually enjoyed an enormous stipend of 3,000 aspers a day during the latter part of her son's reign.[10] When Mehmed III went on the Eger campaign in Hungary in 1596, he gave his mother great power over the empire, leaving her in charge of the treasury. During her interim rule she persuaded her son to revoke a political appointment of the judgeship of Istanbul and to reassign to the grand vizierate to Damat Ibrahim Pasha, her son-in-law.[11]

During this period, the secretary of the English ambassador reported that while in the palace, Safiye "espied a number of boats upon the river [the Bosphorus] hurrying together. The Queen Mother sent to enquire of the matter [and] was told that the Vizier did justice upon certain chabies [kahpe], that is, whores. She, taking displeasure, sent word and advised [the Vizier] that her son had left him to govern the city and not to devour the women; [thus] commanding him to look well to the other business and not to meddle any more with the women till his master's return."[12]

The greatest crisis Safiye endured as a valide sultan stemmed from her reliance on her kira, Esperanza Malchi. A kira was a non-Muslim woman (typically Jewish) who acted as an intermediary between a secluded woman of the harem and the outside world, serving as a business agent and secretary. Malchi reportedly attempted to influence Safiye (and through her the sultan) negatively in their policy toward the Republic of Venice in conflict with the Venetian spy Beatrice Michiel, which on at least one occasion caused an open conflict at court. [13] In 1600, the imperial cavalry rose in rebellion at the influence of Malchi and her son, who had amassed over 50 million aspers in wealth. Safiye was held responsible for this, along with the debased currency the troops were paid with, and nearly suffered the wrath of the soldiers, who brutally killed Malchi and her son. Mehmed III was forced to say "he would counsel his mother and correct his servants." To prevent the soldiers from suspecting her influence over the Sultan, Safiye persuaded Mehmed to have his decrees written out by the Grand Vizier, instead of personally signing them.[14]

Safiye was instrumental in the execution of her grandson Mahmud in 1603, having intercepted a message sent to his mother by a religious seer, who predicted that Mehmed III would die in six months and be succeeded by his son. According to the English ambassador, Mahmud was distressed at "how his father was altogether led by the old Sultana his Grandmother and the state went to Ruin, she respecting nothing but her own desire to get money, and often lamented thereof to his mother," who was "not favored of the Queen mother."[15] The sultan, suspecting a plot and jealous of his son's popularity, had him strangled.

Mehmed III was succeeded by his son Ahmed I in 1603. One of his first major decisions was to deprive his grandmother of power—she was banished to the Old Palace on Friday, 9 January 1604.[16][17] When Ahmed I's brother Mustafa I became sultan in 1617, his mother Halime Sultan received 3,000 aspers as valide sultan although her mother-in-law Safiye was still alive. However, Halime received only 2,000 aspers during her retirement to the Old Palace between her son's two reigns; during the first months of her retirement Safiye was still alive, perhaps a neighbor in the Old Palace, receiving 3,000 aspers a day[1] while the Haseki Sultan of Ahmed I, Kösem Sultan also living in the Old Palace, received 1,000 aspers day.[18]

All succeeding sultans were descended from Safiye.[19]

Foreign relations

Safiye, like Nurbanu, advocated a generally pro-Venetian policy and regularly interceded on behalf of the Venetian ambassadors, one of whom described her to the senate as "a woman of her word, trustworthy, and I call say that in her alone have I found truth in Constantinople; therefore it will always benefit Your Serenity to promote her gratitude."[20]

Safiye also maintained good relations with England. She persuaded Mehmed III to let the English ambassador accompany him on campaign in Hungary.[21] One unique aspect of her career is that she corresponded personally with Queen Elizabeth I of England, volunteering to petition the Sultan on Elizabeth's behalf. The two women also exchanged gifts. On one occasion, Safiye received a portrait of Elizabeth in exchange for "two garments of cloth of silver, one girdle of cloth of silver, [and] two handkerchiefs wrought with massy gold."[22] In a letter from 1599, Safiye responds to Elizabeth's request for good relations between the empires:

I have received your letter...God-willing, I will take action in accordance with what you have written. Be of good heart in this respect. I constantly admonish my son, the Padishah, to act according to the treaty. I do not neglect to speak to him in this manner. God-willing, may you not suffer grief in this respect. May you too always be firm in friendship. God-willing, may [our friendship] never die. You have sent me a carriage and it has been delivered. I accept it with pleasure. And I have sent you a robe, a sash, two large gold-embroidered bath towels, three handkerchiefs, and a ruby and pearl tiara. May you excuse [the unworthiness of the gifts].[23]

Safiye had the carriage covered and used it on excursions to town, which was considered scandalous. This exchange of letters and gifts between Safiye and Elizabeth presented an interesting gender dynamic to their political relationship. In juxtaposition to the traditional means of exchanging women in order to secure diplomatic, economic, or military alliances, Elizabeth and Safiye's exchange put them in the position of power rather than the objects of exchange.[24]

An unusual occurrence in Safiye's relationship with England was her attraction to Paul Pindar, secretary to English ambassador and deliverer of Elizabeth's coach. According to Thomas Dallam (who presented Elizabeth's gift of an organ to Mehmed III), "the sultana did take a great liking to Mr. Pinder, and afterward, she sent for him to have his private company, but their meeting was crossed."[25]

Public works

Safiye is also famous for starting the construction of Yeni Mosque, the "new mosque" in Eminönü, Istanbul, in 1597. Part of Istanbul's Jewish quarter was razed to make way for the structure, whose massive building costs made Safiye unpopular with the soldiery, who wanted her exiled. At one point Mehmed III temporarily sent her to the Old Palace.[26] Though she returned, she did not live to see the mosque completed. After Mehmed died, Safiye lost power and was permanently exiled to the Old Palace. The mosque's construction was halted for decades. It was finally completed in 1665 by another valide sultan, Turhan Hatice, mother of Mehmed IV.

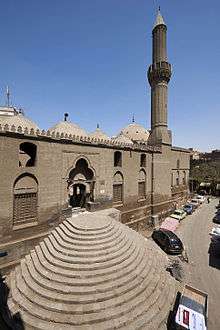

Masjid al-Malika Safiyya

The Al-Malika Safiye Mosque in Cairo is named in Safiye's honor. The mosque of al-Malika Safiyya derives its name more by appropriation than by real patronage. It was started by 'Uthman Agha, who held the post of the Agha Dar al-Sa'ada, or black eunuch in charge of the harem, as well as the Egyptian waqf estates of the holy places in the Hijaz. 'Uthman Agha was the agent and slave of the noble Venetian beauty Safiya, of the Baffo family, who had been captured by corsairs and presented to the imperial harem, where she became chief consort of Sultan Murad III (1574–95) and virtual regent for her son, Sultan Mehmed III (1595-1603). 'Uthman died before the mosque was completed, and it went to Safiya as part of his estate. She endowed the mosque with a deed that provided for thirty-nine custodians including a general supervisor, a preacher, the khatib (orator), two imams, timekeeper, an incense burner, a repairman, and a gardener.[28]

Death

Leslie Peirce points out in her book that Safiye was still alive during the first months of her daughter-in-law's retirement in the Old Palace between Mustafa I's two reigns, which means that she was alive at least until 1619 and died during the reign of her great-grandson Osman II. Safiye was buried in Murad III's tomb.

In popular culture

- In the 2011 TV series Muhteşem Yüzyıl, Young Safiye Sultan is portrayed by Turkish actress Gözde Türker.

- In the 2015 TV series Muhteşem Yüzyıl: Kösem, Safiye Sultan is portrayed by Turkish actress Hülya Avşar.

See also

- Lists of mosques

- List of mosques in Africa

- List of mosques in Egypt

- Ottoman dynasty

- Ottoman family tree

- List of Valide Sultans

- List of consorts of the Ottoman Sultans

Notes

- Leslie Peirce points out in her book that Safiye Sultan was still alive during the first months of her daughter-in-law's retirement in the Old Palace between Mustafa I's two reigns, which means that she was alive at least until 1619.[1]

- Peirce 1993, p. 127.

- Peirce, Leslie P. (1993). The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc. p. 308n2. ISBN 0-19-507673-7.

The identities of Nurbanu Sultan and her daughter-in-law Safiye Sultan are often confused.

- Peirce, Leslie P. (1993). The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc. p. 94. ISBN 0-19-507673-7.

Murad's favorite was Safiye, a concubine said to be of Albanian origin from the village of Rezi in the Ducagini mountains.

- Pedani 2000, p. 11.

- Peirce 1993, p. 95.

- Pedani 2000, p. 13.

- Peirce 1993, p. 94.

- Peirce 1993, p. .

- Pedani 2000, p. 15.

- Peirce 1993, p. 126.

- Peirce 1993, p. 240.

- Peirce 1993, p. 202.

- Ioanna Iordanou, Venice's Secret Service: Organizing Intelligence in the Renaissance

- Peirce 1993, pp. 242-243.

- Peirce 1993, p. 231.

- Börekçi 2009, p. 23.

- Michael, Michalis N.; Kappler, Matthias; Gavriel, Eftihios (2009). Archivum Ottomanicum. p. 187.

- Peirce 1993, pp. 128.

- Alderson 1956, Table XXXI et seq..

- Peirce 1993, p. 223.

- Peirce 1993, p. 226.

- Peirce 1993, p. 219.

- Peirce 1993, p. 228.

- Andrea 2007, p. 13.

- Peirce 1993, p. 225.

- Peirce 1993, p. 242.

- "Photo by alimahmoud177". Photobucket. Retrieved 2016-02-19.

- "Masjid al-Malika Safiyya | Archnet". archnet.org. Retrieved 2016-02-19.

References

- Alderson, A. D. (1956). The Structure of the Ottoman Dynasty. Oxford: Clarendon.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Andrea, Bernadette (2007). Women and Islam in Early Modern English Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-12176-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Börekçi, Günhan (2009). "Ahmed I". In Ágoston, Gábor; Masters, Bruce (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 978-0-8160-6259-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jardine, L. (2004). "Gloriana Rules the Waves: Or, the Advantage of Being Excommunicated (And a Woman)". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 6 (14): 209. doi:10.1017/S0080440104000234.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mitchell, Colin P. (2011). New Perspectives on Safavid Iran: Empire and Society. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-136-99194-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pedani, M. P. (2000). "Safiye's Household and Venetian Diplomacy". Turcica. 32: 9. doi:10.2143/TURC.32.0.460.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Peirce, Leslie Penn (1993). The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire. Studies in Middle Eastern History. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507673-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

| Ottoman royalty | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Nurbanu Sultan |

Haseki Sultan 1575 – 15 January 1595 |

Succeeded by Kösem Sultan |

| Valide Sultan 15 January 1595 – 22 December 1603 |

Succeeded by Handan Sultan | |