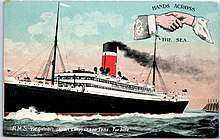

SS Drottningholm

RMS Virginian, was a steam turbine powered transatlantic ocean liner, launched in 1904 for the Allan Line, and one of the few passenger liners to serve in both World Wars. She operated from 1920 to 1948 for the Swedish American Line as SS Drottningholm, and ended her service in 1955 with Home Lines.

SS Drottningholm in port of Boston | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: |

|

| Owner: |

|

| Route: |

|

| Builder: | Alexander Stephen and Sons, Glasgow |

| Launched: | 22 December 1904[1] |

| Maiden voyage: | 6 April 1905[1] |

| Fate: | Feb 1955: scrapped at Trieste |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Passenger liner and cargo |

| Tonnage: | 10,757 gross register tons (GRT)[1] |

| Length: | 538 ft (164 m)[2] |

| Beam: | 60 ft (18 m)[2] |

| Depth: | 38 ft (12 m) |

| Propulsion: | Steam Turbine |

| Speed: | 18 kn (21 mph)[2] |

| Capacity: | 1712 passengers[2] |

Early Career as RMS Virginian

Virginian was built in 1905 by Alexander Stephen and Sons in Glasgow for the Allan Line of Canada.[2] She was a sistership to RMS Victorian and operated in Allan Line service until 1920.[2]

Connection to Titanic Disaster

In 1912, she was one of several ships in wireless radio communication with RMS Titanic, giving iceberg warnings.[3] On April 14, 1912 the Virginian was about 170 miles from the Titanic, heading out of Halifax with 200 passengers onboard. It had received a wireless communication from the Titanic, reporting it had hit an iceberg and required assistance. The Virginian's Captain Gambell would set course at full speed to aid in the rescue. The last signals were heard by the Virginian from the Titanic were at 12:27 A.M., at which point the wireless operator said "the signals become blurred and ended abruptly".[4] At one point erroneous wireless messages had Virginian towing Titanic to Halifax, Nova Scotia and that all on board Titanic were safe. Such a report appeared in the Daily Mirror on 16 April 1912.[5] On April 15, 1912 at 9.00 a.m., a message was sent from the RMS Carpathia to Virginian, "We are leaving here with all on board about 700 passengers. Please return to your Northern course".[6]

World War I

During World War I she served as a troop transport ship for Canada and Armed Merchant Cruiser for Royal Navy.[7] On 21 August 1917 she was damaged by the German submarine U-102.[8]

SS Drottningholm

In 1920, she was sold to the Swedish American Line and renamed SS Drottningholm. In 1922-1923 she was refurbished, re-engined and her superstructure enlarged.[9]

She served Sweden until 1948, notably under the command of Captain John Nordlander.[1]

World War II

The Drottningholm was one of the few passenger liners along with Cunard's RMS Aquitania, to have completed service in both World Wars. During wartime the ship was used as a mercy ship to exchange civilian internees, POWs, and diplomats. She was chartered by the American, British, and French governments for a total of 14 voyages that transported 18,160 individuals.[10]

In March 1942 the ship was chartered by the U.S. State Department via an arrangement with the Nazi Germans and other Axis powers, facilitated with the help of the Swiss and Swedish governments, to repatriate civilian internees and diplomats from both sides of the war.

Her first east bound voyage from the US, carrying Axis individuals, was from New York City to Lisbon, Portugal on May 7, 1942. On May 22, she departed Lisbon for a west bound return trip carrying Allied individuals to New York, arriving on June 1, 1942. The passengers included American Chargé d'affaires to Germany Leland B. Morris and diplomat George Kennan. She made one more east bound voyage to Lisbon on June 3 from Jersey City, New Jersey.[11][12] Her final west bound exchange mission from Lisbon to New York arrived in the United States on June 30. That would be her last exchange trip from Lisbon as the Nazi government cancelled all further trades.[13] On July 15, she left from New York City to her home port in Gothenburg, Sweden, carrying approximately 800 Axis nationals.[14]

She continued to serve the British and French as a repatriation mercy ship.

The Drottningholm carried Red Cross supplies for distribution to other nationals still in Japanese controlled territory. One Japanese national jumped overboard and drowned causing the exchange to be halted until an American offered to stay in captivity.[11]

The Drottningholm was painted white with the name of the vessel in very large letters, the Swedish flag and the words "Sverige" (Sweden) and "Diplomat" painted prominently on port and starboard. She was fully illuminated so her markings could be easily viewed.[11]

On 16 March 1944 she docked in New York after an exchange voyage that took 750 Germans to Europe in exchange for 600 wartime internees, including Mary Berg.[11]

In September 1944, she was being used by the Red Cross to transport POWs and civilians being repatriated from Germany to the UK via Sweden, under the command of Captain John Nordlander. Another voyage in April 1945 docked in Liverpool that included 212 ex-interned Channel Islanders.[15]:172–9

Post-war, the Drottningholm briefly returned to passenger ship service on the Gothenberg - New York transatlantic route until 1948, when it was replaced by the brand new MS Stockholm.[16]

Home Lines as Brasil & Homeland

From 1948–1955 she sailed for the Home Lines of Italy as the Brasil, sailing from Genoa to Rio de Janeiro. The ship was owned by the Home Lines, but was later managed by the Hamburg-Amerika line, rechristened Homeland, and sailed first the Hamburg-Southampton-Halifax-New York route and then the Genoa-Naples-Barcelona-New York route. In 1955, after 50 years of service, she was retired and scrapped in Trieste.[2]

Footnotes

- "Ship Descriptions – V". The Ship List. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- Miller Jr., William (2001). Picture History of British Ocean Liners 1900 to the Present. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-41532-5.

- "TIP | Titanic Related Ships | Virginian | Allan Line". www.titanicinquiry.org. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- Times, Special to The New York (15 April 1912). "Allan Liner Virginian Now Speeding Toward the Big Ship.; BALTIC TO THE RESCUE, TOO". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- "From the Archives: Titanic 100 years on" (PDF). Contact. University of Dundee: 27. April 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- Garber, Megan (13 April 2012). "The Technology That Allowed the Titanic Survivors to Survive". The Atlantic. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- Royal Navy list.

- www.uboat.net: Virginian

- Micke Asklander. "S/S Virginian (1905)". Fakta om Fartyg (in Swedish). Retrieved 22 February 2008.

- "S/S Drottningholm a history". Salship.

- "Drottningholm and Gripsholm The Exchange and Repatriation Voyages During WWII". Salship.

- "Drottningholm Sails With 949 Axis Nationals". Chicago Daily Tribune, June 4, 1942.

- "Nazis Refuse Safe Conduct For Rescue Ship". Chicago Daily Tribune, July 2, 1942.

- "Drottningholm Leaves NY With 800 Axis Nationals". Chicago Daily Tribune, July 16, 1942.

- Harris, Roger E. Islanders deported part 1. ISBN 978-0902633636.

- "NEW SWEDISH SHIP DUE HERE MARCH 1; Comfort Rather Than Luxury Is Keynote on Motorliner Stockholm, Line Reports". The New York Times. 4 January 1948. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 3 June 2020.