Richard Rumbold

Richard Rumbold (1622–1685) was a Parliamentarian soldier and political radical, exiled for his role in the 1683 Rye House Plot and later executed for taking part in the 1685 Argyll's Rising.

Richard Rumbold | |

|---|---|

Rye House, Hertfordshire, Rumbold's residence from 1660 to 1683; 1793 watercolour by J. M. W. Turner | |

| Born | 1622 Royston, Hertfordshire (possibly) |

| Died | 26 June 1685 (aged 62–63) Edinburgh |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1642–1659 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Unit | Cromwell's Regiment |

| Battles/wars | Wars of the Three Kingdoms Dunbar Worcester Argyll's Rising |

During the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, he joined the New Model Army, and was one of the guards at the execution of Charles I of England in January 1649. He reached the rank of Captain before being dismissed from the army after the 1660 Restoration.

Closely involved with radical politics, he was implicated in the 1683 Rye House Plot, an alleged plan to assassinate Charles II of England and his brother James. After it was discovered, he escaped to the Dutch Republic, then took part in the 1685 Argyll's Rising, an unsuccessful attempt to drive James from the throne. Captured after being badly wounded, he was executed at Edinburgh on 26 June 1685.

His speech from the scaffold included the statement "none comes into the world with a saddle on his back, neither any booted and spurred to ride him." These words were quoted during the US Constitutional Convention in 1787, and by Thomas Jefferson shortly before his death in 1826.

Biography

Little is known of Rumbold's background, except that he was born in 1622, and his family came from Hertfordshire, possibly Royston. He had a brother, William, who took part in Monmouth's Rebellion but was pardoned in 1688.[1]

Dismissed from the army following The Restoration in 1660, he married a widow who owned a Malting business based at Rye House, Hertfordshire near Hoddesdon. There is no record of any children from this marriage.[1]

Career

He joined the Parliamentarian army in 1642 and served throughout the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, joining the New Model Army when it was set up in 1645. At some point, Rumbold lost an eye, though it is unclear if this was a battle injury, and as a result was known to his friends as Hannibal. Rumbold was a Baptist, a sect particularly prominent in the New Model, and closely associated with the radical Leveller movement. He claimed to have been present at the execution of Charles I, and in February 1649 was one of those who petitioned for Agitators to be re-appointed to the Army Council.[2]

Oliver Cromwell viewed the Agitators with great hostility, especially after their role in organising the so-called Leveller mutinies in April and May.[3] Rumbold seems to have withdrawn from the group, as his name does not appear on the version of the petition printed by the Levellers, and was rewarded with a commission. During the Third English Civil War, he fought at the battles of Dunbar and Worcester; when it ended in 1651, he was a Lieutenant in Cromwell's Regiment of Horse. He was dismissed from the army with the rank of captain at the 1660 Restoration.[4]

Rumbold remained politically active after the Restoration, and was prominent within radical circles, many of whom were also Baptists and New Model veterans. They included former Agitators Abraham Holmes and John Harris, who were also present at Charles' execution, Rumbold's cousin John Gladman, and his brother William.[4] This group was closely involved in the 1679 to 1681 campaign to exclude the Catholic James from succeeding his brother Charles II. They helped organise the 1680 'Great Petition' demanding the recall of Parliament, signed by 18,000 people, including John Ayloffe, Richard Nelthorpe and Robert Ferguson.[5]

All of the above were implicated in the Rye House Plot. Named after Rumbold's home, the plan was to ambush Charles and his brother as they returned to London from Newmarket in March 1683. Rumbold was reportedly given the task of killing Charles, although there is considerable debate as to how serious it was, or what its objectives were. In his speech from the scaffold in 1685, Rumbold denied any intention of murdering the king, but after warrants for his arrest were issued in June, he escaped to the Dutch Republic.[6]

Here he joined other exiled opponents of the Stuarts. The most prominent were Archibald Campbell, 9th Earl of Argyll, convicted of treason in 1681, and Charles' illegitimate son, James Scott, Duke of Monmouth, exiled for his involvement in the Rye House Plot. Preparations for a rising became more urgent with the accession of James after the death of Charles in February 1685, and the two agreed to work together. To ensure co-ordination, a leading Scots exile, Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun accompanied Monmouth, while Rumbold and Ayloffe went with Argyll.[1]

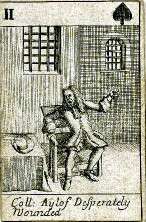

Unfortunately, Argyll's Rising failed to attract significant support, and was fatally compromised by divisions among the rebel leadership, Rumbold being one of the few to emerge with any credit. After Argyll was captured on 18 June, the others were ordered to disperse; intercepted by militia on the night of 20/21 June near Lesmahagow, Rumbold killed one assailant, wounded another two, and was captured only when his horse was shot from under him. Brought to Edinburgh seriously wounded, he was tried, convicted of treason on 26th and executed the same day, allegedly to ensure he did not die of his wounds first.[7]

Ayloffe was executed later that year in London along with Nelthorpe, who served with Monmouth, as did William Rumbold, pardoned in 1688 for his participation.[1] Rumbold made his own defiant declaration on the scaffold:

This is a deluded generation, veiled in ignorance, that though popery and slavery be riding in upon them, do not perceive it; though I am sure that there was no man born marked by God above another; for none comes into this world with a saddle on his back, neither any booted and spurred to ride him...[8]

This echoed words published thirty-seven years earlier by Harris in Mecurius Militaris; 'Children of kings are born with crowns upon their heads, and the people with saddles upon their backs.'[9] They would be quoted again in 1787 during discussions on the definition of treason at the Convention that drew up the Constitution of the United States.[10]

Ten days before his death, Thomas Jefferson also borrowed from Rumbold's speech in his letter of 24 June, 1826 to the Mayor of Washington, D.C.. He wrote, "...All eyes are opened or opening to the rights of man. The general spread of the light of science has already laid open to every view the palpable truth, that the mass of mankind has not been born with saddles on their backs, nor a favored few, booted and spurred, ready to ride them legitimately by the grace of God."[11]

References

- Clifton 2004.

- De Krey 2018, p. 323.

- BCW Project.

- Southern 2001, p. 149.

- Knights 1993, pp. 53-54.

- Marshall 2005.

- Fountainhall 1840, p. 183.

- Howell 1816, p. 882.

- Rees 2016, p. 258.

- Adair 1952, p. 523.

- McCullough 2001, pp. 644-645.

Sources

- Adair, Douglass (1952). "Rumbold's Dying Speech, 1685, and Jefferson's Last Words on Democracy, 1826". The William and Mary Quarterly. 9 (4).

- BCW Project. "The Leveller Mutinies". BCW Project. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- Clifton, Robin (2004). "Rumbold, Richard". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/24269. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- De Krey, Gary S (2018). Following the Levellers, Volume Two: English Political and Religious Radicals from the Commonwealth to the Glorious Revolution, 1649-1688: Volume 2. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1349953295.

- Fountainhall, Lauder (1840). Historical Observes of Memorable Occurrents in Church and State, From October 1680 to April 1686 (2019 ed.). Wentworth Press. ISBN 978-0526064717.

- Howell, Thomas (1816). A Complete Collection of State Trials and Proceedings for High Treason; Volume IX. TC Hansard.

- Knights, Mark (1993). "1680: London's Monster Petition". The Historical Journal. 36 (1). JSTOR 2639515.

- Marshall, Alan (2005). "Rye House Plotters". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/93794. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- McCullough, David (2001). John Adams. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0684813637.

- Rees, John (2016). The Leveller Revolution. Verso. ISBN 978-1784783907.

- Southern, Antonia (2001). Forlorn Hope: Soldier Radicals of the Seventeenth Century. Book Guild Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1857765199.