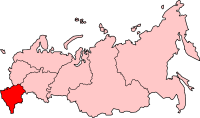

Russian wine

Russian wine refers to wine made in Russia, at times also including the disputed region of Crimea.[1] The vast majority of Russia's territory is unsuitable for grape growing, with most of the production concentrated in parts of Krasnodar and Rostov regions, as well as Crimea.[2]

The Russian market is characterized by the presence of many low-cost products, with a significant part of local wines having a retail price of less than 100 rubles ($1.71).[3] Attempts to shift away from the low-quality reputation of Soviet wines has been moderately successful, though 80% of wines sold in Russia in 2013 were made from grape concentrates.[2]

In 2014 Russia was ranked 11th worldwide by the area of vineyards under cultivation.[3] The Russian wine industry is promoted by local authorities as a healthier alternative to spirits, which have a higher alcohol content.[4]

History

Wild grape vines have grown around the Caspian, Black and Azov seas for thousands of years with evidence of viticulture and cultivation for trade with the Ancient Greeks found along the shores of the Black Sea at Phanagoria and Gorgippia.[5] It is claimed that the Black Sea area is the world's oldest wine region.[6]

The founder of modern commercial wine-making in Russia was Prince Leo Galitzine (1845-1915), who established the first Russian factory of champagne wines at his Crimean estate of Novyi Svet. In 1889 the production of this winery won the Gold Medal at the Paris exhibition in the nomination for sparkling wines, although several years previously the wine regions of Russia had been devastated by the Phylloxera epidemic. In 1891, Galitzine congratulated himself on becoming the surveyor of imperial vineyards at Abrau-Dyurso, where the sparkling wine was produced throughout the 20th century under the brand of Soviet Champagne, or "champagne for the people".

After the Russian Revolution of 1917 the French wine-savvy professionals fled Russia, but the industry was gradually reestablished, starting from 1920. According to Denis Puzyrev, before the 1917 Revolution wine was drunk in Russia only by the aristocracy, a situation that only changed under Soviet rule.[7] The wine industry experienced a rebound in the 1940s and 1950s during the Soviet era until the domestic reforms pushed by Mikhail Gorbachev in 1985 as part of his campaign against alcoholism. After the fall of the Soviet Union, the transition to a market economy with the privatization of land saw many of the area's prime vineyard spaces being utilized for other purposes. By 2000 the entire Russian Federation had only 72,000 hectares (180,000 acres) under cultivation, less than half the total area used in the early 1980s.[5]

Semi-sweet and sweet wines account for 80% of the Russian market, a share exceeding 90% in the economy segment.[7] Since 2006, Russian wineries have adopted European techniques and standards. The Abrau-Durso winery is considered the flagship of the new wine industry.[7]

In 2018 and 2019 several Russian wines were rated by Robert Parker of The Wine Advocate and scored between 80 to 97 points.

In 2020 Fanagoria Blanc de Blancs Brut, a 2017 wine from the Fanagoria Estate Winery in Fanagoria on the Taman Peninsula, was awarded a gold medal at the "Chardonnay du Monde" ("Chardonnay of the World") international tasting competition.[8]

Geography and climate

The climate of the North Caucasus region, where most of Russia's vineyards are located, is typical of a continental region. To counter the severe winters many vine growers will cover their vines over with soil to protect the vines from frost. In the area of Krasnodar there are anywhere from 193-233 frost free days during the growing seasons that allow the vines in the area to grow to full ripening.

The area of Dagestan has a varied climate with some areas semi-desert. About 13 percent of Russian wine is produced in the area around Stavropol which has 180-190 frost free days. The region of Rostov is characterized by its hot, dry summers and severe winters which produces grapes in lower yields than other parts of the country. Nevertheless Rostov is a region with a great diversity of atochtonous grape varieties which originally from the Don Valley including sunch az Tsimlyankskiy Tchernyi, Kumshatskiy, Krasnostop Zolotovskiy, Plechistik and others [9]

Wine and grapes

Russia produces wine of several different styles including still, sparkling and dessert wine. Currently there are over 100 different varieties of grapes used in the production of Russian wine. The Rkatsiteli grape accounts for over 45 percent of production. Other varieties grown include Aligote, Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Severny, Clairette blanche, Merlot, Muscat, Pinot gris, Plavai, Portugieser, Riesling, Saperavi, Silvaner, and Traminer.[9]

Russia currently has the following controlled appellations that correspond to the sorts of grapes: Sibirkovy (Сибирьковый),[10] Tsimlyanski Cherny (Цимлянский чёрный),[11] Plechistik (Плечистик),[12] Narma (Нарма),[13] and Güliabi Dagestanski (Гюляби Дагестанский),[14][9] Krasnostop Zolotovsky (Красностоп Золотовский), Saperavi (Саперави), Platovsky (Платовский), Bastardo Magarachsky (Бастардо Магарачский), Kefesia (Кефесия), Kokur Belyi (Кокур Белый).

A Russian wine guide published in 2012 lists 55 wines from 13 wineries, including names such as Fanagoria, Lefkadia, Chateau du Talus, Abrau-Durso, Chateau le Grand Vostock.[2] The market is largely fragmented, and even the market share of leading producers (such as Kuban-Vino or Viktoria TD) is below 3%.[4]

References

- Jancis Robinson; Julia Harding (2015). The Oxford Companion to Wine. Oxford University Press. p. 633. ISBN 978-0-19-870538-3. Archived from the original on 2017-04-04.

- Puzyrev, Denis (2 May 2013). "Coming soon: A great Russian wine". Russia Beyond The Headlines. Archived from the original on 24 July 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- "Russia Announces Minimum Set Prices for Wine" (PDF). USDA Foreign Agricultural Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 April 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- "Wine in Russia". Euromonitor. Archived from the original on 4 April 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- J. Robinson "The Oxford Companion to Wine" Third Edition pg 597 Oxford University Press 2006 ISBN 0-19-860990-6

- "Home - Russian Wine Country". Russian Wine Country. Archived from the original on 17 December 2014. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- Denis Puzyrev, special to RBTH (13 May 2014). "Raise a glass to Russia's world-class wines". Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 17 December 2014. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- https://www.chardonnay-du-monde.com/wod/WebObjects/Result.woa/wa/res?mod=pays&c=RUSSIE&y=2020&co=CdM&m=*&lang=AG. Retrieved 30 July 2020. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - J. Robinson "The Oxford Companion to Wine" Third Edition pg 598 Oxford University Press 2006 ISBN 0-19-860990-6

- "Сибирьковый". Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- "Цимлянский черный". Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- "Плечистик". Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- "Нарма". Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- "Гюляби дагестанский". Retrieved 17 December 2014.