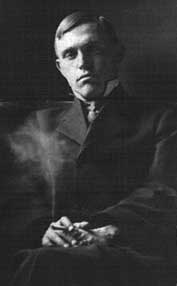

Damon Runyon

Alfred Damon Runyon (October 4, 1880[1][2] – December 10, 1946) was an American newspaperman and short-story writer.[3]

Damon Runyon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Alfred Damon Runyan October 4, 1880 Manhattan, Kansas |

| Died | December 10, 1946 (aged 66) New York City |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Nationality | American |

He was best known for his short stories celebrating the world of Broadway in New York City that grew out of the Prohibition era. To New Yorkers of his generation, a "Damon Runyon character" evoked a distinctive social type from the Brooklyn or Midtown demi-monde. The adjective "Runyonesque" refers to this type of character as well as to the type of situations and dialog that Runyon depicted.[4] He spun humorous and sentimental tales of gamblers, hustlers, actors, and gangsters, few of whom go by "square" names, preferring instead colorful monikers such as "Nathan Detroit", "Benny Southstreet", "Big Jule", "Harry the Horse", "Good Time Charley", "Dave the Dude", or "The Seldom Seen Kid". His distinctive vernacular style is known as "Runyonese": a mixture of formal speech and colorful slang, almost always in present tense, and always devoid of contractions. He is credited with coining the phrase "Hooray Henry", a term now used in British English to describe the upper class version of a loud-mouthed, arrogant twit.

Runyon's fictional world is also known to the general public through the musical Guys and Dolls based on two of his stories, "The Idyll of Miss Sarah Brown" and "Blood Pressure".[5] The musical additionally borrows characters and story elements from a few other Runyon stories, most notably "Pick The Winner". The film Little Miss Marker (and its three remakes, Sorrowful Jones, 40 Pounds of Trouble and the 1980 Little Miss Marker) grew from his short story of the same name.

Runyon was also a newspaper reporter, covering sports and general news for decades for various publications and syndicates owned by William Randolph Hearst. Already known for his fiction, he wrote a well-remembered "present tense" article on Franklin Delano Roosevelt's Presidential inauguration in 1933 for the Universal Service, a Hearst syndicate, which was merged with the co-owned International News Service in 1937.

Life and work

Damon Runyon was born Alfred Damon Runyan to Alfred Lee and Elizabeth (Damon) Runyan.[6] His relatives in his birthplace of Manhattan, Kansas included several newspapermen.[7] His grandfather was a newspaper printer from New Jersey who had relocated to Manhattan, Kansas in 1855, and his father was editor of his own newspaper in the town. In 1882 Runyon's father was forced to sell his newspaper, and the family moved westward. The family eventually settled in Pueblo, Colorado in 1887, where Runyon spent the rest of his youth. By most accounts, he attended school only through the fourth grade.[8] He began to work in the newspaper trade under his father in Pueblo. In present-day Pueblo, Runyon Field, the Damon Runyon Repertory Theater Company, and Runyon Lake are named in his honor.

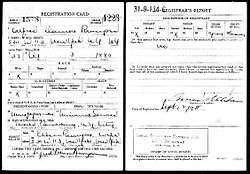

In 1898, when still in his teens, Runyon enlisted in the U.S. Army to fight in the Spanish–American War. While in the service, he was assigned to write for the Manila Freedom and Soldier's Letter.

After his military service, he worked for Colorado newspapers, beginning in Pueblo. His first job as a reporter was in September 1900, when he was hired by the Pueblo Star;[9] he then worked in the Rocky Mountain area during the first decade of the 1900s: at the Denver Daily News, he served as "sporting editor" (what would today be called "sports editor") and then worked as a staff writer. His expertise was in covering the semi-professional teams in Colorado; he even briefly managed a semi-pro team in Trinidad, Colorado.[10] At one of the newspapers where he worked, the spelling of his last name was changed from "Runyan" to "Runyon", a change he let stand.

After failing in an attempt to organize a Colorado minor baseball league, which lasted less than a week,[11] Runyon moved to New York City in 1910. In his first New York byline, the American editor dropped the "Alfred" and the name "Damon Runyon" appeared for the first time. For the next ten years he covered the New York Giants and professional boxing for the New York American.

He was the Hearst newspapers' baseball columnist for many years, beginning in 1911, and his knack for spotting the eccentric and the unusual, on the field or in the stands, is credited with revolutionizing the way baseball was covered. Perhaps as confirmation, Runyon was inducted into the writers' wing (the J. G. Taylor Spink Award) of the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1967. He is also a member of the International Boxing Hall Of Fame and is known for dubbing heavyweight champion James J. Braddock, the "Cinderella Man". Runyon frequently contributed sports poems to the American on boxing and baseball themes, and also wrote numerous short stories and essays.

If I have all the tears that are shed on Broadway by guys in love, I will have enough salt water to start an opposition ocean to the Atlantic and Pacific, with enough left over to run the Great Salt Lake out of business. But I wish to say I never shed any of these tears personally, because I am never in love, and furthermore, barring a bad break, I never expect to be in love, for the way I look at it love is strictly the old phedinkus, and I tell the little guy as much.

from "Tobias the Terrible",

collected in More than Somewhat (1937)

One year, while covering spring training in Texas, he met Pancho Villa in a bar and later accompanied the unsuccessful American expedition into Mexico searching for Villa. It was while he was in Mexico that he met the young girl whom he eventually married.

Gambling, particularly on craps or horse races, was a common theme of Runyon's works, and he was a notorious gambler himself. One of his paraphrases from a line in Ecclesiastes ran: "The race is not always to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, but that's how the smart money bets."

A heavy drinker as a young man, he seems to have quit drinking soon after arriving in New York, after his drinking nearly cost him the courtship of the woman who became his first wife, Ellen Egan. However, he remained a heavy smoker.

His best friend was mobster accountant Otto Berman, and he incorporated Berman into several of his stories under the alias "Regret, the horse player". When Berman was killed in a hit on Berman's boss, Dutch Schultz, Runyon quickly assumed the role of damage control for his deceased friend, correcting erroneous press releases (including one that stated Berman was one of Schultz's gunmen, to which Runyon replied, "Otto would have been as effective a bodyguard as a two-year-old.").

Runyon's marriage to Ellen Egan produced two children (Mary and Damon, Jr.), but broke up in 1928 over rumors that Runyon had become infatuated with Patrice Amati del Grande, a Mexican woman he had first met while covering the Pancho Villa raids in 1916 and discovered once again in New York, when she called the American seeking him out. Runyon had promised her in Mexico that if she would complete the education he paid for her, he would find her a dancing job in New York. She became his companion after he separated from his wife. After Ellen Runyon's death, Runyon and del Grande married on July 7, 1932;[12] that marriage ended in 1946 when she left him for a younger man.

Runyon died in New York City from throat cancer in late 1946, at age 66. His body was cremated, and his ashes were scattered from a DC-3 airplane over Broadway in Manhattan by Captain Eddie Rickenbacker on December 18, 1946. This was an infringement of the law, but widely approved.[13] The family plot of Damon Runyon is located at Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York.

Legacy

- After Runyon's death, his friend and fellow journalist, Walter Winchell, went on his radio program and appealed for contributions to help fight cancer, eventually establishing the Damon Runyon Cancer Memorial Fund to support scientific research into causes of, and prevention of, cancer.[14]

- The first-ever telethon was hosted by Milton Berle in 1949 to raise funds for the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation.

- Each year the Denver Press Club assigns the Damon Runyon Award to a prominent journalist. Past winners include Jimmy Breslin, Mike Royko, George Will and Bob Costas.[15]

- Damon Runyon Elementary school in Littleton, Colorado, is named after him.[16]

- The Damon Runyon Stakes is a thoroughbred horse race run every December at Aqueduct Race Track. Runyon loved horse racing and ran a small stable of his own.

- In the mid-1930s, Runyon persuaded promoter Leo Seltzer to formally change his Roller Derby spectacle from a marathon roller-skating race into a full-contact team sport,[17] an innovation that was eventually revived in a DIY spirit seven decades later.

- One block of West 45th Street (between 8th and 9th Avenues) in Manhattan's Hell's Kitchen is named Runyon's Way.

- The house in Manhattan, Kansas, where Runyon was born is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[7][18]

- In 2008, The Library of America selected "The Eternal Blonde", Runyon's account of a 1927 murder trial, for inclusion in its two-century retrospective of American Crime Writing.

Literary style

The English comedy writer Frank Muir comments[19] that Runyon's plots were, in the manner of O. Henry, neatly constructed with professionally wrought endings, but their distinction lay in the manner of their telling, as the author invented a peculiar argot for his characters to speak. Runyon almost totally avoids the past tense (English humourist E. C. Bentley thought there was only one instance, and was willing to "lay plenty of 6 to 5 that it is nothing but a misprint",[20] but "was" appears in the short stories "The Lily of St Pierre"[21] and "A Piece of Pie";[22] "had" appears in "The Lily of St Pierre",[21] "Undertaker Song"[23] and "Bloodhounds of Broadway"[24]), and makes little use of the future tense, using the present for both. He also avoided the conditional, using instead the future indicative in situations that would normally require conditional. An example: "Now most any doll on Broadway will be very glad indeed to have Handsome Jack Madigan give her a tumble" (Guys and Dolls, "Social error"). Bentley[25] comments that "there is a sort of ungrammatical purity about it [Runyon's resolute avoidance of the past tense], an almost religious exactitude." There is an homage to Runyon that makes use of this peculiarity ("Chronic Offender" by Spider Robinson) which involves a time machine and a man going by the name "Harry the Horse".

He uses many slang terms (which go unexplained in his stories), such as:

- pineapple = pineapple grenade

- roscoe/john roscoe/the old equalizer/that thing = gun

- shiv = knife

- noggin = head

- snoot = nose

There are many recurring composite phrases such as:

- ever-loving wife (occasionally "ever-loving doll")

- more than somewhat (or "no little, and quite some"); this phrase was so typical that it was used as the title of one of his short story collections

- loathe and despise

- one and all

Bentley notes[26] that Runyon's "telling use of the recurrent phrase and fixed epithet" demonstrates a debt to Homer.

Runyon's stories also employ occasional rhyming slang, similar to the cockney variety but native to New York (e.g.: "Miss Missouri Martin makes the following crack one night to her: 'Well, I do not see any Simple Simon on your lean and linger.' This is Miss Missouri Martin's way of saying she sees no diamond on Miss Billy Perry's finger." (from "Romance in the Roaring Forties")).

The comic effect of his style results partly from the juxtaposition of broad slang with mock-pomposity. Women, when not "dolls", "Judies", "pancakes", "tomatoes", or "broads", may be "characters of a female nature", for example. He typically avoided contractions such as "don't" in the example above, which also contributes significantly to the humorously pompous effect. In one sequence, a gangster tells another character to do as he is told, or else "find another world in which to live".

Runyon's short stories are told in the first person by a protagonist who is never named, and whose role is unclear; he knows many gangsters and does not appear to have a job, but he does not admit to any criminal involvement, and seems to be largely a bystander. He describes himself as "being known to one and all as a guy who is just around".[27] The radio program The Damon Runyon Theatre dramatized 52 of Runyon's works in 1949, and for these the protagonist was given the name "Broadway", although it was admitted that this was not his real name, much in the way "Harry the Horse" and "Sorrowful Jones" are aliases.[28]

Literary works

Books

|

|

Stories

There are many collections of Runyon's stories, in particular Runyon on Broadway and Runyon from First to Last. A publisher's note in the latter claims that collection contains all of Runyon's short stories not included in Runyon on Broadway,[29] but two Broadway stories originally published in Collier's Weekly are not in either collection: "Maybe a Queen"[30] and "Leopard's Spots",[31] both collected in More Guys And Dolls (1950). The radio show, in addition, has a story, "Joe Terrace", that does not appear in Runyon's book collections but was published in the August 29, 1936, issue of Colliers. It is one of his "Our Town" stories, and the only episode of the show which is not in Runyonese.

The "Our Town" stories are short vignettes of life in a small town, largely based on Runyon’s experiences in his home town of Pueblo, Colorado. They are written in a simple, descriptive style and contain twists and odd endings based on the personalities of the people involved. Each story’s title is the name of the principal character. Twenty-seven of them were published in the 1946 book In Our Town.

Runyon on Broadway contains the following stories:

|

More Than Somewhat

|

Furthermore

|

Take It Easy

|

Runyon from First to Last includes the following stories and sketches:

|

The First Stories (early non-Broadway stories):

Stories à la Carte (Broadway stories written in Runyonese):

|

|

The Last Stories (Broadway stories written in Runyonese):

Written in Sickness (sketches):

|

Uncollected stories

- The Art of High Grading. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 2 January 1910

- The Sucker. San Francisco Examiner, 10 July 1910

- Joe Terrace. Collier’s, 29 August 1936. An ‘Our Town’ story.

Film

Twenty of his stories became motion pictures.[32]

- Lady for a Day (1933) – Adapted by Robert Riskin, who suggested the name change from Runyon's title "Madame La Gimp", the film garnered Academy Award nominations for Best Picture, Best Director (Frank Capra), Best Actress (May Robson), and Best Adaptation for the Screen (Riskin). It was remade as Pocketful of Miracles in 1961, with Bette Davis in the Apple Annie role (fused with the "raggedy doll" from Runyon's short story "The Brain Goes Home"); Frank Sinatra recorded the upbeat title song (his rendition is not used in the film). The film received Oscar nominations for composers Sammy Cahn and Jimmy Van Heusen and for co-star Peter Falk (Best Supporting Actor). In 1989, Jackie Chan adapted the story yet again for the Hong Kong action film Miracles, adding several of his trademark stunt sequences.

- Little Miss Marker (1934) – The film that made Shirley Temple a star, launched her career, and pushed her past Greta Garbo as the nation's biggest film draw of the year. Also starred Charles Bickford. Subsequent remakes include Sorrowful Jones (1949) with Bob Hope and Lucille Ball; 40 Pounds of Trouble (1962) with Tony Curtis, and Little Miss Marker (1980) with Walter Matthau, Julie Andrews, Bob Newhart and Curtis.

- The Lemon Drop Kid (1934) – Starring Lee Tracy, remade in 1951 with Bob Hope (and I Love Lucy co-star William Frawley appearing in both adaptations); the latter version introduced the Christmas song "Silver Bells".

- Princess O'Hara (1935) – Starring Jean Parker, remade in 1943 as It Ain't Hay with Abbott and Costello and Patsy O'Connor

- Professional Soldier (1935) – an adventure story starring Victor McLaglen and Freddie Bartholomew

- A Slight Case of Murder (1938) with Edward G. Robinson – remade in 1953 as Stop, You're Killing Me with Broderick Crawford and Claire Trevor

- The Big Street (1942) – Henry Fonda, Lucille Ball (adapted from Runyon's story "Little Pinks")

- Butch Minds the Baby (1942) – Broderick Crawford, Shemp Howard

- Johnny One-Eye – (1950) Starring Pat O'Brien, Wayne Morris, Delores Moran, and Gayle Reed

- Money from Home (1953) – Starring Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis

- Guys and Dolls (1955) – Marlon Brando, Jean Simmons, Frank Sinatra, Vivian Blaine, and Stubby Kaye. Blaine and Kaye reprised their roles from the 1950 Broadway production. Adapted from the story "The Idyll of Miss Sarah Brown". The big craps game is adapted from the story "Blood Pressure".

- Bloodhounds of Broadway (1989) – Ensemble cast starring Matt Dillon, Jennifer Grey, Madonna, and Julie Hagerty, among others. The film combines elements from four stories into one large one: "A Very Honorable Guy", "The Brain Goes Home", "Social Error", and "The Bloodhounds of Broadway".

In 1938, his unproduced play Saratoga Chips became the basis of The Ritz Brothers film Straight, Place and Show.

Plays and musicals

- A Slight Case of Murder (1935) co-written for Broadway with Howard Lindsay[33]

- Guys and Dolls (1950) starring Robert Alda (Sky Masterson), Vivian Blaine (Miss Adelaide), Sam Levene (Nathan Detroit), Isabel Bigley (Sarah Brown), Pat Rooney Sr., B.S. Pully, Stubby Kaye, Johnny Silver, Tom Pedi. Adapted from Runyon's stories "The Idyll of Miss Sarah Brown" and "Blood Pressure".

Radio

The Damon Runyon Theater radio series dramatized 52 of Runyon's short stories in weekly broadcasts running from October 1948 to September 1949 (with reruns until 1951).[34][35] The series was produced by Alan Ladd's Mayfair Transcription Company for syndication to local radio stations. John Brown played the character "Broadway", who doubled as host and narrator. The cast also comprised Alan Reed, Luis Van Rooten, Joseph Du Val, Gerald Mohr, Frank Lovejoy, Herb Vigran, Sheldon Leonard, William Conrad, Jeff Chandler, Lionel Stander, Sidney Miller, Olive Deering and Joe De Santis. Pat O'Brien was initially engaged for the role of "Broadway". The original stories were adapted for the radio by Russell Hughes.

"Broadway's New York had a crisis each week, though the streets had a rose-tinged aura", wrote radio historian John Dunning. "The sad shows then were all the sadder; plays like For a Pal had a special poignance. The bulk of Runyon's work had been untapped by radio, and the well was deep."[36]:189

Television

Damon Runyon Theatre aired on CBS-TV from 1955 to 1956.

Mike McShane told Runyon stories as monologues on British TV in 1994, and an accompanying book was released, both called Broadway Stories.

See also

References

- "Birth Announcement". The (Manhattan, Kansas) Nationalist. October 7, 1880.

- http://www.cityofmhk.com/DocumentCenter/Home/View/1049

- Philip Pullman, Nick Hardcastle (1998). Detective stories. Kingfisher Publications. ISBN 0-7534-5636-2.

- Webber, Elizabeth; Feinsilber, Mike (1999). Merriam-Webster's dictionary of allusions, page 479–480. ISBN 978-0-87779-628-2.

- "Damon Runyon". Authors. The eBooks-Library. Retrieved 2008-07-20.

- Maxine Block, editor. "Current Biography, 1942 edition". H.H. Wilson, 1942, p. 723.

- Manhattan's historic landmarks & districts: Damon Runyon House (Kansas State Historical Society National Register of Historic Places – Nomination form), cityofmhk.com. Retrieved March 20, 2012.

- "The Press: Hand Me My Kady". Time magazine, December 23, 1946, n.p.

- "The Press: Broadway Columnist". Time magazine, September 30, 1940, n.p.

- "An All-Star Team Picked by A.D. Runyon". Denver Daily News, September 15, 1907, p. S2.

- Robert Phipps. "Long Evening Kills League". Omaha World Herald, December 21, 1946, p. 7

- New York, New York, Marriage Index 1866-1937

- Eddie Rickenbacker: An American Hero in the Twentieth Century, by W. David Lewis, pg. 506.

- Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation

- John C. Ensslin. "Denver Press Club's Damon Runyon Award for contributions in the field of journalism". Denver Press Club. Archived from the original on November 8, 2010. Retrieved June 22, 2010.

- Damon Runyon Elementary school

- Turczyn, Coury (January 28, 1999). "Blood on the Tracks". Metro Pulse. Archived from the original on February 28, 2008. Retrieved February 11, 2008. (link points to the archived article in the Spring 2000 edition of the author's own PopCult Magazine website): "The faster skaters would break out and try and get laps so they would get ahead in the race, and some of the slower skaters started to band together to try and hold them back", says Seltzer. "And at first, they didn’t want to let them do that – but then the people liked it so much, they kind of allowed blocking. Then they came down to Miami – I think it was 1936, early '37 – and Damon Runyon, a very famous sports writer, saw it and he sat down with my father and hammered out the rules, almost exactly as they are today."

- What buildings in Riley County are on the Historic Register? Archived 2011-10-14 at the Wayback Machine. Riley County Official Website, www.rileycountyks.gov. Retrieved March 20, 2012.

- The Oxford Book of Humorous Prose (1990), OUP, p. 621

- Runyon on Broadway, Pan Books, 1975, p. 11

- Runyon on Broadway, Pan Books, 1975, p. 116

- Runyon on Broadway, Pan Books, 1975, p. 536

- Runyon on Broadway, Pan Books, 1975, p. 258

- Runyon on Broadway, Pan Books, 1975, p. 85

- Introduction to More Than Somewhat, included in omnibus volume Runyon on Broadway (1950), Constable

- Introduction to Furthermore, included in omnibus volume Runyon on Broadway (1950), Constable.

- Runyon on Broadway, Pan Books, 1975, p. 12

- Damon Runyon Theater

- Publisher's Note included in Runyon from First to Last (1954), Constable

- Collier's Weekly, December 12, 1931: https://www.unz.org/Pub/Colliers-1931dec12

- Collier's Weekly, May 6, 1939: https://www.unz.org/Pub/Colliers-1939may06

- "Essay and Annotations" by Daniel R. Schwarz, Guys and Dolls and Other Writings, 2008. Penguin Classics, UK. p. 616.

- "Essay and Annotations" by Daniel R. Schwartz, Guys and Dolls and Other Writings, 2008. Penguin Classics, UK. p. 625.

- "The Damon Runyon Theatre". The Digital Deli Too. Archived from the original on January 27, 2012. Retrieved March 9, 2012.

- Goldin, David J. (2012). "The Damon Runyon Theatre", radioGOLDINdex database. Retrieved March 9, 2012.

- Dunning, John (1998). On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio (Hardcover; revised edition of Tune in Yesterday (1976) ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-19-507678-3. Retrieved 2019-10-04.

The Damon Runyon Theater, dramatic anthology.

Further reading

- Breslin, Jimmy (1991). Damon Runyon: A Life. London: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-89919-984-9

- Clark, Tom (1978). The World of Damon Runyon. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-010771-0

- D'Itri, Patricia Ward (1982). Damon Runyon. Boston: Twayne. ISBN 978-0-8057-7336-1

- Hoyt, Edwin P (1964). A Gentleman of Broadway: The Story of Damon Runyon. Boston: Little Brown. ISBN 978-1-199-45217-7

- Mosedale, John (1981). The Men Who Invented Broadway: Damon Runyon, Walter Winchell & Their World. New York: Richard Marek Publishers. ISBN 978-0-399-90085-3

- Runyon, Damon Jr (1953). Father's Footsteps: The Story of Damon Runyon by his Son. New York: Random House

- Schwarz, Daniel R (2003). Broadway Boogie Woogie: Damon Runyon and the Making of New York City Culture. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-312-23948-0

- Wagner, Jean (1965). Runyonese: The Mind and Craft of Damon Runyon. Paris: Stechert-Hafner. ASIN B0007ILK4K

- Weiner, Ed (1948). The Damon Runyon Story. New York: Longmans Green. ASIN B0007DPA5U

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Damon Runyon. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Damon Runyon |

- Works by Damon Runyon at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Damon Runyon at Internet Archive

- Baseball Hall of Fame

- All the stories from: More than Somewhat, Furthermore, & Take it Easy at Project Gutenberg Australia

- Text of story "The Informal Execution of Soupbone Pew" at Project Gutenberg Australia

- The Damon Runyon Theatre – audio files of the complete series at the Internet Archive

- Damon Runyon on IMDb

- Damon Runyon at the Internet Broadway Database

- Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation and Broadway Theater Service

- Damon Runyon Papers. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.