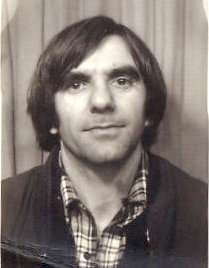

Rudi Dutschke

Alfred Willi Rudolf Dutschke (German: [ˈʁuːdi ˈdʊtʃkə]; 7 March 1940 – 24 December 1979) was a German Marxist sociologist and a political activist in the German student movement and the APO protest movement of the 1960s.

Rudi Dutschke | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Alfred Willi Rudolf Dutschke 7 March 1940 Schönefeld, Brandenburg, Germany |

| Died | 24 December 1979 (aged 39) Århus, Denmark |

| Cause of death | Drowning following epileptic seizure |

| Alma mater | Freie Universität Berlin |

| Known for | Spokesperson of the German student movement |

| Home town | Luckenwalde, East Germany |

| Spouse(s) | Gretchen Klotz ( m. 1966) |

| Children | 3 |

He advocated a "long march through the institutions of power" to create radical change from within government and society by becoming an integral part of the machinery.[1] This was an idea he took up from his interpretation of Antonio Gramsci and the Frankfurt School of Critical Theory;[2] accordingly, the quote is often wrongfully attributed to Gramsci.[3] In the 1970s he followed through on this idea by joining the nascent Green movement.

He survived an assassination attempt by Josef Bachmann in 1968, but died 11 years later from a seizure brought on from brain damage sustained during the assassination attempt. Radical students blamed an anti-student campaign in the papers of the Axel Springer publishing empire for the assassination attempt. This led to attempts to blockade the distribution of Springer newspapers all over Germany, which in turn led to major street battles in many German cities, considered the largest protests to that date in Germany.[4][5]

Early life

Dutschke was born in Schönefeld (present-day Nuthe-Urstromtal) near Luckenwalde, Brandenburg, the 4th son of a postal clerk. Raised in East Germany (GDR), he attended school and graduated from the Gymnasium there. Interested in the ideas of religious socialism, he was engaged in the youth organisation of the East German Evangelical Church. In 1956 he joined the socialist Free German Youth aiming at a sporting career as a decathlete.[6]

In the same year he witnessed the Hungarian Uprising and began to advocate the ideals of a democratic socialism beyond the official line of the Socialist Unity Party.[7][8][9] He obtained his Abitur degree in 1958 and completed an apprenticeship as an industrial clerk. As he refused to join the East Germany National People's Army and convinced many of his fellow students to refuse as well, he was prevented from attending university in the GDR.[10] In August 1961, Dutschke fled to the Marienfelde transit camp in West Berlin, just three days before the Berlin Wall was built.[11]

He began to study sociology, ethnology, philosophy and history at the Free University of Berlin under Richard Löwenthal and Klaus Meschkat where he became acquainted with the existentialist theories of Martin Heidegger and Jean-Paul Sartre, and soon after also with alternative views of Marxism and the history of the labour movement.[12][13] Dutschke joined the German SDS Sozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund (which was not the same as the SDS in the US, but quite similar in goals) in 1965 and from that time on the SDS became the center of the student movement, growing very rapidly and organizing demonstrations against the war in Vietnam.[14]

He married the American Gretchen Klotz (de) in 1966. They had three children. Dutschke's third child, 1980-born Rudi-Marek Dutschke was born after his father's death. He is a politician of the German Green Party[15] as well as Dean's Office staffer of the Hertie School of Governance[16] today. His older siblings are Hosea-Che Dutschke (named after the Old Testament minor prophet Hosea and Che Guevara) and their sister Polly-Nicole, both born in 1968.[11][12]

Political views

Influenced by critical theory, Rosa Luxemburg, and critical Marxists and informed through his collaboration with fellow students from Africa and Latin America, Dutschke developed a theory and code of practice of social change via the practice of developing democracy in the process of revolutionizing society, collaborating with foreign students.[17]

Dutschke also advocated that the transformation of Western societies should go hand in hand with Third World liberation movements and with democratization in communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe. He was from a pious Lutheran family[18] and his socialism had strongly Christian roots; he called Jesus Christ the "greatest revolutionary", and in Easter 1963, he wrote that "Jesus is risen. The decisive revolution in world history has happened – a revolution of all-conquering love. If people would fully receive this revealed love into their own existence, into the reality of the 'now', then the logic of insanity could no longer continue."[19]

Benno Ohnesorg's death in 1967 at the hands of German police pushed some in the student movement toward increasingly extremist violence and the formation of the Red Army Faction. The violence against Dutschke further radicalised parts of the student movement into committing several bombings and murders. Dutschke rejected this direction and feared that it would harm or cause the dissolution of the student movement. Instead he advocated a 'long march through the institutions' of power to create radical change from within government and society by becoming an integral part of the machinery.[1] The meaning of Dutschke's idea of a "long march through the institutions" is in fact highly contested: most historians of '68 in West Germany understand it to mean advocating setting up an alternative society and recreating the institutions which were seen by Dutschke as beyond reform in their current state. It is highly unlikely Dutschke would have promoted change from within the parliamentary and judicial system, which were populated by former Nazis and political conservatives.[20] This is made clear in the SDS reaction to the Kiesinger-led CDU-SPD grand coalition and the authoritarian Emergency Laws they passed.[21]

Shooting and later life

On 11 April 1968, Dutschke was shot in the head by a young anti-communist, Josef Bachmann.[22] Dutschke survived the assassination attempt, and he and his family went to the United Kingdom in the hope that he could recuperate there. Dutschke and Bachmann shared correspondence over the next year, until Bachmann's suicide in 1970.[23] Dutschke was accepted at Clare Hall, a graduate college at the University of Cambridge, to finish his degree in 1969, but in 1971 the Conservative government under Edward Heath expelled him and his family as an "undesirable alien" who had engaged in "subversive activity", causing a political storm in London. They then moved to Århus, Denmark, after professor Johannes Sløk had offered him a job at the University of Aarhus which made it possible for Dutschke to gain a Danish residence permit.[24][25]

Dutschke re-entered the German political scene after protests against the building of nuclear power plants activated a new movement in the mid-1970s. He also began working with dissidents opposing the Communist governments in East Germany, Poland, Yugoslavia, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia, including Robert Havemann, Wolf Biermann, Milan Horáček, Adam Michnik and others.[26][27][28]

Because of brain damage sustained in the assassination attempt, Dutschke continued to suffer health problems. He died on 24 December 1979 in Århus. He had an epileptic seizure while in the bathtub and drowned.[22][29]

In 2018, it emerged that Rudolf Augstein, publisher of Der Spiegel, provided financial support to Dutschke so he could continue to work on his dissertations. Between 1970 and 1973, he paid 1,000 German Marks per year. At the same time they started an exchange of letters in which they also discussed the student revolts.[30]

Works

- Dutschke, Rudi (1980), Mein langer Marsch: Reden, Schriften und Tagebücher aus zwanzig Jahren (in German), Hamburg, DE: Rowohlt.

- Dutschke, Rudi (2003), Dutschke, Gretchen (ed.), Jeder hat sein Leben ganz zu leben (diaries) (in German), Köln, DE: Kiepenheuer & Witsch, ISBN 3-462-03224-0 (1963–1979).

- Dutschke, Rudi (Summer 1982), "It Is Not Easy to Walk Upright", TELOS, New York: Telos Press (52).

Bibliography

- Dutschke, Gretchen (1996), Wir hatten ein barbarisches, schönes Leben (biography) (in German), Köln, DE: Kiepenheuer & Witsch, ISBN 3-462-02573-2.

- Michaela Karl: Rudi Dutschke – Revolutionär ohne Revolution. Neue Kritik, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-8015-0364-X.

- Bernd Rabehl: Rudi Dutschke – Revolutionär im geteilten Deutschland. Edition Antaios, Dresden 2002, ISBN 3-935063-06-7.

- Rudi-Marek Dutschke: Spuren meines Vaters. Kiepenheuer und Witsch, Köln 2001, ISBN 3-462-03038-8.

- Jutta Ditfurth: Rudi und Ulrike: Geschichte einer Freundschaft. Droemer Knaur, München 2008, ISBN 3-426-27456-6.

- Tilman P. Fichter, Siegward Lönnendonker Dutschkes Deutschland. Der Sozialistische Deutsche Studentenbund, die nationale Frage und die DDR-Kritik von links. Klartext, Essen 2011, ISBN 978-3-8375-0481-1.

- Willi Baer, Karl-Heinz Dellwo Rudi Dutschke – Aufrecht Gehen. 1968 und der libertäre Kommunismus, Laika, Hamburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-942281-81-2.

- Carsten Prien: Dutschkismus - die politische Theorie Rudi Dutschkes, Ousia Lesekreis Verlag, Seedorf 2015, ISBN 978-3-944570-58-7.

References

- Huffmann, Richard (March 2004), "The Limits of Violence", Satya, Baader Meinhof, archived from the original on 11 November 2008.

- Schwanitz, Dietrich (29 June 1998), "Frankfurter Schule und Studentenbewegung", Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German), Marcuse.

- q:Antonio Gramsci

- Hockenos, Paul (19 May 2008), "Taz Year Thirty", The Nation.

- Sontheimer, Michael (9 April 2018). "Attentat vor 50 Jahren: Drei Kugeln auf Rudi Dutschke". Spiegel Online. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- Miermeister, Jürgen (1986). Rudi Dutschke: mit Selbstzeugnissen und Bilddokumenten (in German). Rowohlt. ISBN 9783499503498.

- "Wie Dutschkes Weltbild entstand". www.rbb-online.de (in German). Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- "Mythos Rudi Dutschke: Der verhinderte Stadtguerillero". Spiegel Online. 7 April 2008. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- WELT (28 May 2009). "Studentenbewegung: Dutschke schrieb über seine Angst vor der Stasi". DIE WELT. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ": "WIR FORDERN DIE ENTEIGNUNG AXEL SPRINGERS"". Der Spiegel. 29. 10 July 1967. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- Chaussy, Ulrich (26 February 2018). Rudi Dutschke. Die Biographie (in German). Droemer eBook. ISBN 9783426451410.

- Dutschke-Klotz, Gretchen (1996). Rudi Dutschke. Köln: Kiepenheuer und Witsch. pp. 38-, 53-, 172, 227, 459. ISBN 978-3-462-02573-6.

- "The Attack on Rudi Dutschke: A Revolutionary Who Shaped a Generation". Spiegel Online. 11 April 2008. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- Hamill, Virginia (26 December 1979). "Rudi Dutschke, 39, Led German Student Revolt". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- "Rudi Marek Dutschke", Kandidatenwatch, DE, archived from the original on 29 September 2008.

- Hertie-school.

- Slobodian, Quinn, "2", Foreign Front: Third World Politics in Sixties West Germany, Duke University Press, archived from the original on 5 February 2013.

- Paul Hockenos (2007). Joschka Fischer and the Making of the Berlin Republic: An Alternative History of Postwar Germany. Oxford University Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-19-029283-6.

- Frank, Helmut (16–20 April 2003), "Ich liebte diesen naiven Christen", Sonntagsblatt (in German), Bayern, DE, archived from the original on 18 July 2011.

- Davis, Belinda; Mausbach, Wilfried; Klimke, Martin (eds.), Changing the World, Changing Oneself: Political Protest and Collective Identities in West Germany and the U.S. in the 1960s and 1970s.

- "STUDENTEN / DUTSCHKE: Der lange Marsch". Der Spiegel. 51. 11 December 1967. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- Burleigh, Michael (2011). Blood and Rage: History of Terrorism. HarperCollins. p. 230. ISBN 9780062047175.

- "Lieber Josef Bachmann: Diese Briefe schrieb Dutschke an seinen Attentäter". Der Bild. 27 April 2010. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- Halter, Hans (19 August 1996). ": "Herz der Revolte"". Der Spiegel. 34. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- 6112@au.dk (15 February 2018). "Rudi Dutschke (1940–1979)". www.au.dk (in Danish). Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- Mayer, Margit; Ely, John (1998). The German Greens: Paradox Between Movement and Party. Temple University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-56639-516-8.

- Engelmann, Roger; Kowalczuk, Ilko-Sascha (2005). Volkserhebung gegen den SED-Staat: eine Bestandsaufnahme zum 17. Juni 1953. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. p. 364. ISBN 978-3-525-35004-1.

- Cornils, Ingo (2016). Writing the Revolution: The Construction of "1968" in Germany. Boydell & Brewer. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-57113-954-2.

- Wendland, Johannes (2009). "Erinnerungen: Hosea Dutschke über den Tod seines Vaters vor 30 Jahren" [Memories: Hosea Dutschke on His Father's Death 30 Years Ago]. Spiegel Online (in German). Der Spiegel. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- "Bislang unbekannte Akten: "Spiegel"-Gründer Augstein unterstützte Dutschke finanziell". FAZ.NET (in German). ISSN 0174-4909. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rudi Dutschke. |

- Rudi Dutschke on IMDb

- Rudi Dutschke in the German National Library catalogue

- Dutschke, Rudi (biography) (in German), DE: German Historic Museum.

- Salvatore, Gaston (2008), "Lost in the Federal Republic, Scenes from Another Era", Dossier 1968, retrieved 11 November 2012.