Royal Niger Company

The Royal Niger Company was a mercantile company chartered by the British government in the nineteenth century. It was formed in 1879 as the United African Company and renamed to National African Company in 1881 and to Royal Niger Company in 1886. In 1929 the company became part of the United Africa Company,[1] which came under the control of Unilever in the 1930s and continued to exist as a subsidiary of Unilever until 1987, when it was absorbed into the parent company.[2]

The company existed for a comparatively short time (1879–1900) but was instrumental in the formation of Colonial Nigeria, as it enabled the British Empire to establish control over the lower Niger against the German competition led by Bismarck during the 1890s. In 1900, the company-controlled territories became the Southern Nigeria Protectorate, which was in turn united with the Northern Nigeria Protectorate to form the Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria in 1914 (which eventually gained independence within the same borders as the Federal Republic of Nigeria in 1960).

United African Company

Richard Lander first explored the area of Nigeria as the servant of Hugh Clapperton. In 1830, he returned to the river with his brother John; in 1832, he returned again (without his brother) to establish a trading post for the "African Steamship Company"[3] at the confluence of the Niger and Benue rivers. The expedition failed, with 40 of the 49 members dying of fever or wounds from native attacks. One of the survivors, Macgregor Laird, subsequently remained in Britain but directed and funded expeditions to the country until his death in 1861. He opposed the failed Niger expedition of 1841 but the success of the Pleiad’s first mission in 1854 led to annual trips under Baikie and the 1857 foundation of Lokoja at the Niger–Benue confluence.

There were no voyages for the three years following Laird's death, but the establishment of the West African Company was soon followed by several other firms. The competition reduced prices to the point that profits were minimal. Arriving in the region in 1877,[4] George Goldie argued for the amalgamation of the surviving British firms into a single monopolistic chartered company, a method contemporaries supposed had been buried with the ultimate failure of the East India Company following the Sepoy Rebellion. By 1879, he had helped combine James Crowther's WAC, David Macintosh's Central African Company, and the William Brothers' and James Pinnock's firms into a single United African Company; he then acted as the combined firm's agent in the territory.[5]

Almost immediately, the firm saw renewed competition as two French firms—the French Equatorial African Association and the Senegal Company—and another English one—the Liverpool and Manchester Trading Company—begin establishing posts on the river as well.[6] A native attack on the UAC's outpost at Onitsha in 1879 was repulsed with help from HMS Pioneer[5] but the Gladstone administration subsequently denied Goldie's attempt to procure a government charter in 1881, on the grounds that the international rivalry might occasion unnecessary conflict and that the united firm was undercapitalized for the expense of genuine colonial administration.[6]

National African Company

Goldie first began addressing the administration's concerns by increasing the company's capitalization to £100 000. He then managed to corral £1 000 000 in investments in a new concern—the National African Company—which bought up the UAC and its interests in 1882.[7] The death of Léon Gambetta the same year deprived the French companies of their support within the French government and the strong subsidies it had been providing them.[6] Goldie's cash-flush NAC was then able to maintain 30 trading posts along the river[5] and ruin its competition in a two-year price war: by October 1884 all three had permitted him to buy out their interests in the region and the NAC's annual report for 1885 was able to crow that it "remained alone in undisputed commercial possession of the Niger–Binué region".[6]

This monopoly permitted Britain to resist French and German calls to internationalize trade on the Niger river during the negotiations at the 1884–1885 Berlin Conference on African colonization. Goldie himself attended the meetings and successfully argued for including the region of the NAC's operations within a British sphere of interest. Pledges from him and the British diplomats that free trade (or, in any case, non-discriminatory tariff rates) would be respected in their territory were dead letters: the NAC's over 400 treaties with local leaders obliged the natives to trade solely with or through the company's agents. Large tariffs and license fees eliminated competing firms from the area. The terms of these private contracts were made into general treaties by the British consuls, whose own treaties expressly incorporated them.[8] Similarly, when King Jaja of Opobo organized his own trading network and even began running his own shipments of palm oil to Britain, he was lured onto a British warship and shipped into exile on Saint Vincent on charges of "treaty breaking" and "obstructing commerce".[4]

Despite treaties extending British control over the tribes of the Cameroons, however, Britain was willing to recognize the German colony that usurped the area in 1885[8] as a check on French activity in the upper Congo and Ubangi watersheds.

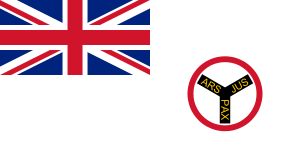

The scruples of the British government being overcome, a charter was at length granted (July 1886), the National African Company becoming The Royal Niger Company Chartered and Limited[1] (normally shortened to the Royal Niger Company), with Lord Aberdare as governor and Goldie as vice-governor.[9]

Niger Company

It was, however, evidently impossible for a chartered company to hold its own against the state-supported protectorates of France and Germany, and in consequence its charter was revoked in 1899[10] and, on 1 January 1900, the Royal Niger Company transferred its territories to the British Government for the sum of £865,000. The ceded territory together with the small Niger Coast Protectorate, already under imperial control, was formed into the two protectorates of northern and southern Nigeria.[9]

The company changed its name to The Niger Company Ltd and in 1929 became part of the United Africa Company.[1] The United Africa Company came under the control of Unilever in the 1930s and continued to exist as a subsidiary of Unilever until 1987, when it was absorbed into the parent company.[2]

See also

- Alhassan Dantata

- Royal Niger Company’s Medal

- Postage stamps and postal history of the Niger Territories

- Sokoto

References

- Baker, Geoffrey L (1996). Trade Winds on the Niger: Saga of the Royal Niger Company, 1830-1971. London: Radcliffe Press. ISBN 978-1860640148.

- Tayo, Ayomide O. (26 July 2019). "How Nigeria transformed from a business into a country". Pulse NG. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

-

- Máthé-Shires, László. "Lagos Colony and Oil Rivers Protectorate" in the Encyclopedia of African History, Vol. 3, pp. 791–792. Accessed 5 Apr 2014.

- Geary, Sir William N.M. (1927), pp. 174 ff.

- McPhee, Allan. The Economic Revolution in British West Africa, pp. 75 ff. Frank Cass & Co. Ltd. (Abingdon), 1926 and reprinted 1971. Accessed 4 Apr 2014.

- "Chartered Companies" in the Encyclopædia Britannica, 10th ed.

- Geary, Sir William Nevill Montgomerie. Nigeria under British Rule, p. 95. Frank Cass & Co, 1927. Accessed 5 Apr 2014.

-

- Falola, Toyin; Heaton, Matthew (2008). A History of Nigeria. Cambridge University Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0521681575.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Royal Niger Company. |

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 19 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 677–684.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 17 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 115–116.