Roxana: The Fortunate Mistress

Roxana: The Fortunate Mistress (full title: The Fortunate Mistress: Or, A History of the Life and Vast Variety of Fortunes of Mademoiselle de Beleau, Afterwards Called the Countess de Wintselsheim, in Germany, Being the Person known by the Name of the Lady Roxana, in the Time of King Charles II) is a 1724 novel by Daniel Defoe.

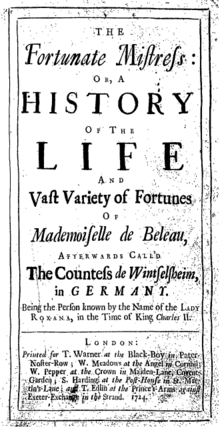

Title page from the first edition | |

| Author | Daniel Defoe |

|---|---|

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Novel |

Publication date | 1724 |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 379 |

Plot summary

Born in France, from which her parents fled because of religious persecution, Roxana grew to adolescence in England. At the age of fifteen, she married a handsome but conceited man. After eight years of marriage, during which time her husband went through all of their money, Roxana is left penniless with five children. She appeals for aid to her husband's relatives, all of whom refuse her except one old aunt, who is in no position to help her materially. Amy, Roxana's maid, refuses to leave her mistress although she receives no wages for her work. Another poor old woman whom Roxana had aided during her former prosperity adds her efforts to those of the old aunt and Amy. Finally, Amy plots to force the five children at the house of the sister of Roxana's fled husband, which she does. The cruel sister-in-law will raise the five children, with the help of her kinder husband.

Roxana is penniless and at the point of despair when Mr. ——, her landlord, after expressing his admiration for her, praises her fortitude under all of her difficulties and offers to set her up in housekeeping. He returns all the furniture he had confiscated, gives her food and money, and generally conducts himself with such kindness and candor that Amy urges Roxana to become the gentleman's mistress should he ask it. Roxana, however, clings to her virtuous independence. Fearing that the gentleman's kindness will go unrewarded, Amy, because she loves her mistress, offers to lie with the landlord in Roxana's place. This offer, however, Roxana refuses to consider. The two women talk much about the merits of the landlord, his motive in befriending Roxana, and the moral implications of his attentions.

When the landlord comes to take residence as a boarder in Roxana's house, he proposes, since his wife has deserted him, that he and Roxana live as husband and wife. To show his good faith, he offers to share his wealth with her, bequeathing her five hundred pounds in his will and promising seven thousand pounds if he leaves her. There is a festive celebration that evening and a little joking about Amy's offer to lie with the gentleman. Finally Roxana, her conscience still bothering her, yields to his protestations of love and has sex with him.

After a year and a half has passed and Roxana has not conceived a child, Amy chides her mistress for her barrenness. Feeling that Mr. —— is not her true husband, Roxana sends Amy to him to beget a child. Amy does bear a child, which Roxana takes as her own to save the maid embarrassment. Two years later, Roxana has a daughter, who dies within six weeks. A year later, she pleases her lover with a son.

Mr. —— takes Roxana with him to Paris on business. There they live in great style until Roxana has a vision in which Mr. —— dies and tries to convince him to stay. To reassure her he gives the case of valuable jewels he carries with him to her, should he be robbed. This ominous assertion proves true and was murdered by thieves after the case of jewels which he was rumored to always carry. Roxana manages to retain the gentleman's wealth and secure it against the possible claims of his wife or any of his living relatives.

Roxana moves up through the social spectrum by becoming the mistress of a German prince who came to pay his respects to her following the jeweler's murder. After carrying on the affair for some time, she becomes pregnant with his child, so he sets her up in a country house just outside of Paris where she can give birth to the child bringing any scandal down upon the Prince. Their relationship is an affectionate one, with the Prince seeming to spend a great deal of time with Roxana despite having a wife. Nevertheless, Roxana has some regrets about the situation her newest son has been born into; destined to be marked by the low status of his mother, and the illegitimacy of the relationship between her and his father. Later, Roxana and the Prince travel to Italy where he has business to attend to, and there they live together for two years. During this time she is gifted a Turkish slave who teaches her the Turkish language and Turkish customs, and a Turkish dress which will become central to her later character development. Also in Italy, Roxana gives birth to another son, however this child does not survive long. Upon their return to Paris, the Prince's wife (the Princess) become ill and dies. The prince, humbled and repentant, decides to no longer keep Roxana as a mistress and live a life closer to God.

As a result, Roxana decides to return to England, but being considerably richer than when she arrived thanks to the jeweler and the Prince, she gets in contact with a Dutch merchant who could help her to move her considerable wealth back to England. Roxana wishes to sell the jewels in the case the jeweler had left her the day he died, and the Dutch merchant arranges for them to be appraised by a Jew. The Jew recognized the jewels as being the ones which had been allegedly stolen from an English jeweler many years prior. The Jew demands that she should be brought to the police, for she was surely the thief, and plots to keep the jewels for himself. The Dutch merchant alerts Roxana of the Jew's scheme and they devise a plan to get her out of France and secure her passage to England through Holland.

Roxana successfully evades the Jew and the law and ends up safely in Holland where the Dutch merchant joins her. The merchant courts her and manages to bed her, hoping she would then agree to marry him. Roxana makes her intentions to remain single clear, to the merchant's astonishment. Roxana ends up becoming pregnant, which makes the Merchant plead for her to marry him so that the child should not be a bastard, which she still refuses. Roxana returns to England on a ship which nearly founders in a storm, on which Amy is stricken with guilt for her sins and wicked ways, but Roxana believes there is no truth in sea storm repentance and promises, so she herself does not feel the need to repent as Amy does: but she realizes that anything Amy is guilty of, she is much more guilty of. Upon arriving in England Amy sets Roxana's estate up in London as Roxana returns to get the other half of her money in Holland.

Roxana sets herself up in Pall Mall, invests her money, and becomes a great hostess in England where she becomes famous for her parties and the Turkish dress she wears and the Turkish dance the slave taught her. This exotic display earns her the name of Roxana (prior to this moment, Roxana is never named, we only know she is called Roxana through this incident, but that her true name is Susan, according to a comment she makes later about her daughter.) She quickly gains a lot of attention, and a three-year gap is announced, and implies she even became mistress to the King, who saw her at one of her parties. Following this she becomes an old man's mistress, which she becomes quickly sick of. Her reputation as a mistress and a whore tires her, and she wishes to lead a more simple life.

Roxana moves to the outskirts of London and takes board in a Quaker woman's house, with whom she quickly becomes friends. This modest house allows her to become a new person and hide from those who may want to harm her. One day she comes across the Dutch merchant who had helped her return to England, and marriage is envisaged. Roxana finally relents on her wish to remain independent and they marry. Hoping to avoid the children from her first marriage should they come looking for her, she moves to Holland with the Dutch merchant where she becomes a countess to her great pleasure.

However, her new life is threatened by the reappearance of her oldest daughter, Susan (which Roxana admits to be named after her, unveiling possibly her true name). Susan's motives to have her mother recognize her as her daughter are unclear. Nevertheless, Roxana feels threatened, and Amy proposes to murder her. The novel ends on ambiguity as to whether Amy actually kills Susan. Roxana only laments the crime that has tainted her life, strongly suggesting Susan was murdered for Roxana to retain her status and reputation.

The text ends on an "unfinished" note, with Roxana living in wealth with her husband in Holland, but assuring the reader that events eventually bring her low and she repents for her actions and experiences a downturn in fortune.

Themes

The novel examines the possibility of eighteenth-century women owning their own estate despite a patriarchal society, as with Roxana's celebrated claim that "the Marriage Contract is ... nothing but giving up Liberty, Estate, Authority, and everything, to the Man".[1] The novel further draws attention to the incompatibility between sexual freedom and freedom from motherhood: Roxana becomes pregnant many times due to her sexual exploits, and it is one of her children, Susan, who come back to expose her, years later, near the novel's close,[2] helping to precipitate her flight abroad, subsequent loss of wealth, and (ambiguous) repentance.[3]

The character of Roxana can be described as a proto-feminist because she carries out her actions of prostitution for her own ends of freedom but before a feminist ideology was fully formed, (though Defoe also works to undercut the radicalism of her position).[4] The book also explores the clash of values between the Restoration court and the middle-class.[5]

Roxana also discusses the issues of truth and deceit. As the text is a first-person narration and written to simulate a real first-hand account of a woman, first comes the issue of subjectivity, but also the underlying lie as to the veracity of the text. The reader can only trust in Roxana to give us a true account of her story, but as she often lies to other characters in the book, and even to herself, she is not a reliable narrator. Furthermore, the whole construction of her character is made on lies and disguises. Her name, or names, are not mentioned until the end of the novel, so even the most basic aspect of her identity—her name—is a mystery for the majority of the novel. And the name that is most associated to her: Roxana, is based on a lie and on a disguise, namely the Turkish dress.

Influence

Published anonymously, and not attributed to Defoe till 1775, Roxana was nonetheless a popular hit in the eighteenth century, frequently reprinted in altered versions to suit the taste of the day: thus the 1775 edition, which called itself The New Roxana, had been sentimentalised to meet the tastes of the day.[6] Only gradually from the 19th century onwards did the novel begin to be treated as serious literature: Ethel Wilson has been one of the 20th century authors subsequently influenced by its matter-of-factness and freedom from cant.[7]

See also

References

- M. M. Boardman, Narrative Innovation and Incoherence (1992) p. 48

- M. M. Boardman, Narrative Innovation and Incoherence (1992) p. 57

- John Mullan ed., Roxana (2008) pp. x–xi, 329–30

- M. M. Boardman, Narrative Innovation and Incoherence (1992) p. 49–50

- A. H. King, Daniel Defoe's Erotic Economics (2009) p. 212

- John Mullan ed., Roxana (2008) pp. 337–39

- D. Stouck, Ethel Wilson (2011) p.184

Further reading

- David Wallace Spielman. 2012. "The Value of Money in Robinson Crusoe, Moll Flanders, and Roxana". Modern Language Review, 107(1): 65–87.

- Susanne Scholz. 2012. "English Women in Oriental Dress: Playing the Turk in Lady Mary Wortley Montagu's Turkish Embassy Letters and Daniel Defoe's Roxana". Early Modern Encounters with the Islamic East: Performing Cultures. Eds. Sabine Schülting, Savine Lucia Müller, and Ralf Herte. Farnam, England: Ashgate. 85–98.

- Robin Runia. 2011. "Rewriting Roxana: Eighteenth-Century Narrative Form and Sympathy". Otherness: Essays and Studies, 2(1).

- Christina L. Healey. 2009. "'A Perfect Retreat Indeed': Speculation, Surveillance, and Space in Defoe's Roxana". Eighteenth-Century Fiction. 21(4): 493512.

- Gerald J. Butler. "Defoe and the End of Epic Adventure: The Example of Roxana". Adventure: An Eighteenth-Century Idiom: Essays on the Daring and the Bold as a Pre-Modern Medium. Eds. Serge Soupel, Kevin L. Cope, Alexander Pettit, and Laura Thomason Wood. New York: AMS. 91–109.

- John Mullan. 2008. "Introduction". Roxana. Ed. John Mullan. Oxford: Oxford University Press. vii–xxvii.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Roxana at Project Gutenberg

- Lady Roxana