Roekiah

Roekiah (Perfected Spelling: Rukiah; 1917 – 2 September 1945), often credited as Miss Roekiah,[lower-alpha 1] was an Indonesian kroncong singer and film actress. The daughter of two stage performers, she began her career at the age of seven; by 1932 she had become well known in Batavia, Dutch East Indies (now Jakarta, Indonesia), as a singer and stage actress. Around this time she met Kartolo, whom she married in 1934. The two acted in the 1937 hit film Terang Boelan, in which Roekiah and Rd Mochtar played young lovers.

Roekiah | |

|---|---|

Roekiah, c. 1941 | |

| Born | 1917 |

| Died | 2 September 1945 (aged 27–28) Djakarta, Indonesia |

| Occupation | Actress, singer |

| Years active | 1920s–1944 |

Notable work | Terang Boelan |

| Spouse(s) | Kartolo |

| Children | 5 |

After the film's commercial success, Roekiah, Kartolo, and most of the cast and crew of Terang Boelan were signed to Tan's Film, first appearing for the company in their 1938 production Fatima. They acted together in two more films before Mochtar left the company in 1940; through these films, Roekiah and Mochtar became the colony's first on-screen couple. Mochtar's replacement, Rd Djoemala, acted with Roekiah in four films, although these were less successful. After the Japanese invaded the Indies in 1942, Roekiah took only one more film role before her death; most of her time was used entertaining Japanese forces.

During her life Roekiah was a fashion and beauty icon, featuring in advertisements and drawing comparisons to Dorothy Lamour and Janet Gaynor. Though most of the films in which she appeared are now lost, she has continued to be cited as a film pioneer, and a 1969 article stated that "in her time [Roekiah] reached a level of popularity which, one could say, has not been seen since".[1] Of her five children with Kartolo, one – Rachmat Kartolo – entered acting.

Biography

Early life

Roekiah was born in Bandoeng (now known as Bandung), West Java, Dutch East Indies, in 1917 to Mohammad Ali and Ningsih, actors with the Opera Poesi Indra Bangsawan troupe;[2] Ali was originally from Belitung, while Ningsih was of Sundanese descent and came from Cianjur.[3] Though Roekiah learned acting mainly from her parents, she also studied the craft with other members of their troupe.[4] The trio were constantly travelling, leaving Roekiah with no time for a formal education.[5] By the mid-1920s they were with another troupe, the Opera Rochani.[6]

Roekiah insisted on becoming an actress, despite the opposition of her family, and asked her mother for permission to perform on stage. Ningsih agreed, with one condition: Roekiah could only perform once. When the seven-year-old Roekiah took to the stage for the first time, Mohammad Ali – unaware of the agreement between his wife and daughter – rushed on stage and insisted that Roekiah stop singing. Afterwards, she refused to eat until her parents ultimately relented.[7] Roekiah performed regularly afterwards with the troupe.[4]

By 1932, the year she joined Palestina Opera in Batavia (modern-day Jakarta), Roekiah had become a well-known stage actress and singer of kroncong music (traditional music with Portuguese influences). She was admired not only for her voice, but her beauty.[8] While with Palestina she met Kartolo, an actor, pianist, and songwriter with the troupe; they married later that year. The new couple soon left Palestina, taking month's hiatus before joining the group Faroka on a tour in Singapore. They returned to the Indies in 1936.[9]

Film career

Partnership with Rd Mochtar

%2C_cover.jpg)

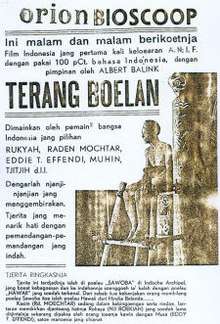

In 1937 Roekiah made her first film appearance as the leading lady in Albert Balink's Terang Boelan (Full Moon). She and her co-star Rd Mochtar[lower-alpha 2] played two lovers who elope so that Roekiah's character need not marry an opium smuggler;[6] Kartolo also had a small role. The film was a commercial success, earning over 200,000 Straits dollars during its international release;[10] the Indonesian film historian Misbach Yusa Biran credited Roekiah as the "dynamite" which led to this positive reception.[11]

Despite the success of Terang Boelan, its production company Algemeen Nederlandsch Indisch Filmsyndicaat stopped all work on fiction films.[11] Now jobless and depressed after the death of her mother, according to journalist W. Imong, Roekiah "kept silent, constantly musing as if she were mentally disturbed".[lower-alpha 3][12] In order to distract his wife, Kartolo gathered the other cast members from Terang Boelan and established the Terang Boelan Troupe, which toured to Singapore to popular acclaim; this snapped Roekiah out of her melancholy.[12] After the troupe returned to the Indies, most of the cast switched to Tan's Film,[13] including Roekiah and Kartolo; the two also performed with the Lief Java kroncong group.[lower-alpha 4][12]

With Tan's, the Terang Boelan cast appeared in the 1938 hit Fatima, starring Roekiah and Rd Mochtar. The film, in which Roekiah played the title role – a young woman who must fend away the advances of a gang leader while falling in love with a fisherman (Rd Mochtar) – closely followed the formula established by Terang Boelan.[lower-alpha 5][14] Roekiah's acting received wide praise. One reviewer in the Batavia-based Het Nieuws van den dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië wrote that Roekiah's "sober personification of injustice in the Malay adat wedding captivates even the European spectator",[lower-alpha 6][15] while another, in the Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad, found that Roekiah's performance was appreciated by everyone.[16]

Fatima was a massive commercial hit, earning 200,000 gulden on a 7,000 gulden budget.[17] Following the film's success, Tan's continued to cast Roekiah with Rd Mochtar.[18] They became the colony's first on-screen celebrity couple and were termed the Indies' Charles Farrell–Janet Gaynor.[1] The popularity of Roekiah–Rd Mochtar as a screen couple led other studios to follow with their own romantic pairings. The Teng Chun's Java Industrial Film, for instance, paired Mohamad Mochtar and Hadidjah in Alang-Alang (Grass, 1939).[19]

In order to keep their new star, Tan's Film spent a large amount of money. Roekiah and Kartolo received a monthly holding fee of 150 gulden and 50 gulden respectively, twice as much as they had been given for Terang Boelan. They were also given a house in Tanah Rendah, Batavia.[20] Roekiah and Kartolo, for their part, continued to act for the company; Kartolo often had small, comedic, roles, and Roekiah sang songs her husband had written.[6] In 1939 they appeared together, again with Rd Mochtar as Roekiah's romantic foil, in the Zorro-influenced Gagak Item. Though not as successful as Roekiah's previous works, the film was still profitable.[21] A reviewer for the Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad praised Roekiah's "demure" acting.[lower-alpha 7][22]

Roekiah's last film with Rd Mochtar, Siti Akbari, was released in 1940. Possibly inspired by a poem of the same name by Lie Kim Hok, the film featured Roekiah in the title role, portraying a long-suffering wife who remains faithful to her husband despite his infidelity.[23] The film was well-received, earning 1,000 gulden on its first night in Surabaya,[24] but was ultimately unable to return profits similar to Terang Boelan or Fatima.[21]

Partnership with Djoemala

Amidst a wage dispute, Rd Mochtar left Tan's for their competitor Populair Films in 1940. Accordingly, the company began looking for a new on-screen partner for Roekiah.[25] Kartolo asked an acquaintance, a tailor-cum-entrepreneur named Ismail Djoemala to take the part; though Djoemala had never acted before, he had sung with the group Malay Pemoeda in 1929. After Kartolo asked him six times to act for Tan's, Djoemala agreed.[26] The company found the tall and good-looking Djoemala a suitable replacement,[20] and hired him, giving him the stage name Rd Djoemala.[27]

Roekiah and Djoemala made their first film together, Sorga Ka Toedjoe (Seventh Heaven), later that year. In the film, Roekiah played a young woman who, with the help of her lover, is able to reunite her blind aunt (Annie Landouw) with her estranged husband (Kartolo).[28] This film was a commercial success,[29] and the reviews were positive. One, for the Soerabaijasch Handelsblad, opined that Djoemala was as good as, if not better, than Rd Mochtar.[30] Another review, for the Singapore Free Press, wrote that "Roekiah fills the part of the heroine in a most praiseworthy manner".[31] In April of the following year Tan's released Roekihati, starring Roekiah as a young woman who goes to the city to earn money for her ailing family, ultimately marrying.[32] Her performance received praise from the Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad, which wrote that she had performed well in the difficult role.[33]

Later in 1941 Roekiah and Djoemala completed Poesaka Terpendam (Buried Treasure),[29] an action-filled film which followed two groups – the rightful heirs (Roekiah being one of them) and a band of criminals – in a race to find treasure buried in Banten.[34] Roekiah and Djoemala worked on their final film together, Koeda Sembrani (The Enchanted Horse), in early 1942. In the film, adapted from One Thousand and One Nights, Roekiah took the role of Princess Shams-al-Nahar and was shown flying on a horse.[35] The film was still incomplete when the Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies began in March 1942,[36] though it was screened by October 1943.[37]

Altogether Roekiah and Djoemala acted in four films in two years. Biran argues this is evidence the company "wasted their treasure",[lower-alpha 8] as its competitors used their stars more often; Java Industrial Film, for instance, completed six films starring Moh. Mochtar in 1941 alone.[29] Though Roekiah's films continued to be financial successes,[19] they did not earn as large a profit as her earlier works.[38]

Japanese occupation and death

Film production in the Indies declined after the Japanese occupation began in early 1942; the overlords forced all but one studio to close.[39] In their place, the Japanese opened their own studio in the Indies, Nippon Eigasha, to produce propaganda for the war effort.[40] Kartolo acted in the studio's only feature film, Berdjoang (Hope of the South), without Roekiah in 1943.[41] After a hiatus of several years, Roekiah also acted for the studio, taking a role in the short Japanese propaganda film Ke Seberang (To the Other Side) in 1944.[6] However, much of her time was spent touring Java with a theatrical company, entertaining Japanese troops.[42]

Roekiah fell ill in February 1945, not long after completing Ke Seberang. Despite this, and a miscarriage, she was unable to rest; the Japanese forces insisted that she and Kartolo go on tour to Surabaya, in eastern Java. Upon her return to Jakarta,[lower-alpha 9] her condition became worse.[42] After several months of treatment, she died on 2 September 1945, mere weeks after Indonesia proclaimed its independence.[43] The date she died was also the day of Japan's surrender which formally ended World War II and the occupation. Roekiah was buried in Kober Hulu, Jatinegara, Djakarta.[42] Her funeral was attended by several luminaries, including the Minister of Education Ki Hajar Dewantara.[44]

Family

Roekiah said that she felt Kartolo was a good match with her, stating that the marriage brought them "great fortune".[lower-alpha 10] The two had had five children.[4] After Roekiah's death, Kartolo brought the children to his hometown at Yogyakarta.[41] In order to support the family, he took a job with Radio Republik Indonesia, beginning in 1946. There he spent most of the ongoing Indonesian National Revolution, an armed conflict and diplomatic struggle between newly proclaimed Indonesia and the Dutch Empire in which the newly proclaimed country attempted to receive international recognition of its independence. After the Dutch military launched Operation Kraai on 19 December 1948, capturing Yogyakarta, Kartolo refused to collaborate with the returning colonial forces. Without a source of income, he fell ill, and died on 18 January 1949.[4]

One of the couple's children died in Yogyakarta, aged ten.[45] The remaining children were brought to Jakarta after the Indonesian National Revolution ended in 1950, where they were raised by Kartolo's close friend Adikarso. One, Rachmat Kartolo, went on to be a singer and actor active up through the 1970s,[41] known for songs such as "Patah Hati" ("Heartbroken") and films such as Matjan Kemajoran (Tiger of Kemayoran; 1965) and Bernafas dalam Lumpur (Breathing in the Mud; 1970).[46] Two other sons, Jusuf and Imam, played in a band with their brother before finding careers elsewhere. The couple's daughter, Sri Wahjuni, did not enter the entertainment industry.[45]

Legacy

The press viewed Roekiah fondly, and her new releases consistently received positive reviews.[40] At the peak of Roekiah's popularity, fans based their fashion decisions on what Roekiah wore on-screen.[44] Roekiah appeared regularly in advertisements,[lower-alpha 11] and numerous records with her vocal performances were available on the market. One fan, in a 1996 interview, recalled that Roekiah was "every man's idol",[lower-alpha 12][46] while others christened Roekiah as Indonesia's Dorothy Lamour.[2] Another fan, recalling a performance he had witnessed over fifty years earlier, stated:

Roekiah always left her audiences riveted to their seats when she began crooning her kroncong songs. She always got applause, before or after singing. Not only from the native [Indonesians]. Many Dutchmen diligently watched her performances![lower-alpha 13]

After Roekiah's death, the Indonesian film industry searched for a replacement. The film scholar Ekky Imanjaya notes one instance where a film was advertised with the line "Roekiah? No! But Sofia in a new Indonesian film, Air Mata Mengalir di Tjitarum".[lower-alpha 14][47] Roekiah's films were screened regularly,[47] but most are now lost. Movies were then shot on flammable nitrate film, and after a fire destroyed much of Produksi Film Negara's warehouse in 1952, old films shot on nitrate were deliberately destroyed.[48] Of Roekiah's œuvre, JB Kristanto's Katalog Film Indonesia only records Koeda Sembrani as being stored at Indonesia's film archive, Sinematek Indonesia.[49]

Writings about Roekiah after her death often cite her as an idol of Indonesia's film industry.[44] Imanjaya describes her as one of the industry's first beauty icons; he also credits her and Rd Mocthar with introducing the concept of bankable stars to domestic cinema.[19] Moderna magazine, in 1969, wrote that "in her time [Roekiah] reached a level of popularity which, one could say, has not been seen since".[lower-alpha 15][1] In 1977 Keluarga magazine styled her one of Indonesia's "pioneering film stars",[lower-alpha 16][2] writing that hers was "a natural talent, a combination of her personality and the tenderness and beauty of her face, always filled with romance".[lower-alpha 17][50]

Filmography

- Terang Boelan (Full Moon; 1937)

- Fatima (1938)

- Gagak Item (Black Raven; 1939)

- Siti Akbari (1940)

- Sorga Ka Toedjoe (Seventh Heaven; 1940)

- Roekihati (1940)

- Poesaka Terpendam (Buried Treasure; 1941)

- Koeda Sembrani (The Enchanted Horse; 1942)

- Ke Seberang (To the Other Side; 1944; short film)

Explanatory notes

- In the early 20th-century Dutch East Indies, female stage performers, especially kroncong singers, were billed with "Miss" on advertisements (JCG, Roekiah, Miss). Roekiah was also credited as "Roekia" in contemporary advertisements.

- Rd is an abbreviation of the Javanese honorific Raden, used by the nobility.

- Original: "... soeka diam-diam, bermenoeng-menoeng sebagai seorang jang mengandoeng sakit djiwa."

- This group provided the music for Tan's films throughout 1940 and 1941.

- This pattern was eventually followed by all of Roekiah's films.

- Original: "Haar sobere verpersoonlijking van het onrecht in de Maleische huwelijks adat boeit en pakt zelfs den Europeeschen toeschouwer."

- Original: "... ingetogen ..."

- Original: "... menyia-nyiakan hartanya ini."

- Batavia was renamed at the beginning of the Japanese occupation.

- Original: "Pernikahanku dengan Kartolo ternyata mendatangkan banyak rejeki".

- This included advertisements for Singer sewing machines and Matjan-brand sandals from Bata (Biran 2009, p. 24).

- Original: "Dulu Roekiah menjadi idola setiap pria!"

- Original: "Roekiah selalu membuat penonton terlena di bangkunya saat ia mengalunkan lagu kroncong. Ia selalu mendapatkan tepuk tangan, sebelum atau sesudah bernyanyi. Bukan hanya kalangan pribumi. Banyak Belanda yang rajin menonton pertunjukan Roekiah!

- Original: "Roekiah? Bukan! Tetapi Sofia dalam pilem Indonesia baru: Air Mengalir di Tjitarum."

- Original: "... didalam djamannja telah mentjapai suatu popularitas jang boleh dikatakan sampai sekarang belum ada bandingnja".

- Original: "... Perintis Bintang Film Indonesia..."

- Original: "Bakat permainannya dalam film adalah bakat alam yang merupakan perpaduan pribadinya dengan pancaran kelembutan keayuan wajahnya yang penuh romantik."

References

- Moderna 1969, Miss Roekiah, p. 30.

- Keluarga 1977, Miss Roekiah, p. 4.

- Imanjaya 2006, p. 109; Imong 1941, Riwajat Roekiah–Kartolo, p. 24

- Berita Minggu Film 1982, Roekiah, p. V.

- Imong 1941, Riwajat Roekiah–Kartolo, p. 24.

- Filmindonesia.or.id, Roekiah.

- Berita Buana 1996, Roekiah, pp. 1, 6; Imong 1941, Riwajat Roekiah–Kartolo, p. 24

- Keluarga 1977, Miss Roekiah, p. 4; van der Heide 2002, p. 128

- Biran 2009, p. 204; Imong 1941, Riwajat Roekiah–Kartolo, p. 26

- Biran 2009, p. 171.

- Biran 2009, p. 172.

- Imong 1941, Riwajat Roekiah–Kartolo, p. 26.

- Biran 2009, p. 174.

- Filmindonesia.or.id, Fatima.

- Het Nieuws 1939, Nieuwe Films.

- Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad 1939, Fatima.

- Biran 2009, p. 175.

- Biran 2009, p. 176.

- Imanjaya 2006, p. 109.

- Biran 2009, p. 223.

- Biran 2009, p. 212.

- Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad 1939, Gagak Item.

- Filmindonesia.or.id, Siti Akbari.

- Soerabaijasch Handelsblad 1940, Film Sampoerna.

- Biran 2009, p. 227.

- Pertjatoeran Doenia 1942, Ismail Djoemala, p. 8.

- Biran 2009, p. 249.

- L. 1940, n.p.

- Biran 2009, p. 224.

- Soerabaijasch Handelsblad 1940, Sampoerna.

- Singapore Free Press 1941, A Malay Film.

- Filmindonesia.or.id, Roekihati.

- Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad 1941, Roekihati.

- Pertjatoeran Doenia 1941, Poesaka Terpendam.

- Pertjatoeran Doenia 1942, Studio Nieuws, p. 17.

- Biran 2009, p. 282.

- Pembangoen 1943, Pertoendjoekan.

- Keluarga 1977, Miss Roekiah, p. 5.

- Biran 2009, pp. 319, 332.

- Keluarga 1977, Miss Roekiah, p. 6.

- Filmindonesia.or.id, Kartolo.

- Keluarga 1977, Miss Roekiah, p. 7.

- Moderna 1969, Miss Roekiah, p. 34; Tjahaja 1945, Roekiah Meninggal

- TIM, Roekiah.

- Moderna 1969, Miss Roekiah, p. 34.

- Berita Buana 1996, Roekiah, p. 6.

- Imanjaya 2006, p. 111.

- Biran 2012, p. 291.

- Filmindonesia.or.id, Koeda Sembrani.

- Keluarga 1977, Miss Roekiah, pp. 5–6.

Works cited

- "A Malay Film". The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser. 10 March 1941. p. 7. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- Biran, Misbach Yusa (2009). Sejarah Film 1900–1950: Bikin Film di Jawa [History of Film 1900–1950: Making Films in Java] (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Komunitas Bamboo working with the Jakarta Art Council. ISBN 978-979-3731-58-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Biran, Misbach Yusa (2012). "Film di Masa Kolonial" [Film in the Colonial Period]. Indonesia dalam Arus Sejarah: Masa Pergerakan Kebangsaan [Indonesia in the Flow of Time: The Nationalist Movement] (in Indonesian). V. Jakarta: Ministry of Education and Culture. pp. 268–93. ISBN 978-979-9226-97-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Fatima". filmindonesia.or.id (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Konfiden Foundation. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- "Filmaankondiging Cinema: Fatima" [Film Review, Cinema: Fatima]. Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad (in Dutch). Batavia: Kolff & Co. 25 April 1939. p. 3. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- "Filmaankondiging Cinema Palace: 'Gagak Item'" [Film Review, Cinema Palace: 'Gagak Item']. Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad (in Dutch). Batavia: Kolff & Co. 21 December 1939. p. 12. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- "Filmaankondiging Rex: "Roekihati"" [Film Review, Rex: "Roekihati"]. Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad (in Dutch). Batavia: Kolff & Co. 23 April 1941. p. 3. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- "Film Sampoerna: Siti Akbari" [Film at Sampoerna: Siti Akbari]. Soerabaijasch Handelsblad (in Dutch). Surabaya. 7 May 1940. p. 6. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- van der Heide, William (2002). Malaysian Cinema, Asian Film: Border Crossings and National Cultures. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-90-5356-580-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Imanjaya, Ekky (2006). A to Z about Indonesian Film (in Indonesian). Bandung: Mizan. ISBN 978-979-752-367-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Imong, W. (July 1941). "Riwajat Roekiah–Kartolo" [History of Roekiah–Kartolo]. Pertjatoeran Doenia dan Film (in Indonesian). Batavia. 1 (2): 24–26.

- "Ismail Djoemala: Dari Doenia Dagang ke Doenia Film" [Ismail Djoemala: From Enterprise to Film]. Pertjatoeran Doenia dan Film (in Indonesian). Batavia. 1 (9): 7–8. February 1942.

- "Kartolo". filmindonesia.or.id (in Indonesian). Konfiden Foundation. Archived from the original on 22 September 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- "Koeda Sembrani". filmindonesia.or.id (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Konfiden Foundation. Archived from the original on 26 July 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- L. (1940). Sorga Ka Toedjoe [Seventh Heaven] (in Indonesian). Yogyakarta: Kolff-Buning. OCLC 41906099.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (book acquired from the collection of Museum Tamansiswa Dewantara Kirti Griya, Yogyakarta)

- "Miss Roekiah: Artis Teladan" [Miss Roekiah: Talented Artist]. Moderna (in Indonesian). Jakarta. 1 (6): 30, 34. 1969.

- "Miss Roekiah: Perintis Bintang Film Indonesia" [Miss Roekiah: Pioneering Indonesian Film Actress]. Keluarga (in Indonesian). Jakarta (4): 4–7. 24 June 1977.

- "Nieuwe Films, Cinema-Palace" [New Film, Cinema-Palace]. Het Nieuws van den dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië (in Dutch). Batavia. 25 April 1939. p. 6. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- "Pertoendjoekan Bioskop-Bioskop di Djakarta Ini Malam (28 Oktober 2603)" [Showing in Theatres Tonight (28 October 1943)]. Pembangoen (in Indonesian). Jakarta. 28 October 1943. p. 4. Archived from the original on 2 January 2014. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- "Poesaka Terpendam" [Buried Treasure]. Pertjatoeran Doenia dan Film (in Indonesian). Batavia. 1 (4): 40. September 1941.

- "Roekiah". filmindonesia.or.id (in Indonesian). Konfiden Foundation. Archived from the original on 13 August 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- "Roekiah" (in Indonesian). Taman Ismail Marzuki. Archived from the original on 13 August 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- "Roekiah Bintangtonil, Film, dan Musik Pujaan Semua Orang" [Roekiah: Stage, Film, and Music Star Praised by All]. Berita Buana Minggu (in Indonesian). Jakarta. 13 October 1996. pp. 1, 6.

- "Roekiah Kartolo: Primadona Opera "Palestina" dan Pelopor Dunia Layar Perak" [Roekiah Kartolo: Primadona of "Palestina" Opera and Pioneer of the Silver Screen]. Berita Minggu Film (in Indonesian). Jakarta: V, XI. 12–18 December 1982.

- "Roekiah Meninggal Doenia" [Roekiah Passes Away]. Tjahaja (in Indonesian). Bandung. 3 September 1945. p. 2. Archived from the original on 15 June 2014. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- "Roekiah, Miss". Encyclopedia of Jakarta (in Indonesian). Jakarta City Government. Archived from the original on 13 August 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- "Roekihati". filmindonesia.or.id. Jakarta: Konfiden Foundation. Archived from the original on 25 July 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- "Sampoerna: Sorga ka Toedjoe (In den zevenden hemel)" [Sampoerna: Sorga ka Toedjoe (Seventh Heaven)]. Soerabaijasch Handelsblad (in Dutch). Surabaya: Kolff & Co. 30 October 1940. p. 6. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- "Siti Akbari". filmindonesia.or.id (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Konfiden Foundation. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- "Studio Nieuws" [Studio News]. Pertjatoeran Doenia dan Film (in Indonesian). Batavia. 1 (9): 19–21. February 1942.