Roberto Aizenberg

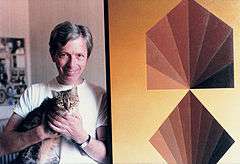

Roberto Aizenberg (22 August 1928 – 16 February 1996), nicknamed "Bobby", was an Argentine painter and sculptor. He was considered the best-known orthodox surrealist painter in Argentina.[1]

Roberto Aizenberg | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 22 August 1928 |

| Died | 16 February 1996 (aged 67) Buenos Aires, Argentina |

| Nationality | Argentinian |

| Education | Colegio Nacional de Buenos Aires; Antonio Berni; Juan Batlle Planas |

| Known for | Painting, Sculpture |

| Movement | Surrealism |

| Spouse(s) | Matilde Herrera |

| Website | www |

Early years

Aizenberg was the son of a Russian-Jewish immigrant who settled in the Jewish agricultural colonies of Entre Ríos Province, in the town of Villa Federal. When he was eight years old, his family moved to La Paternal, a neighborhood in Buenos Aires. He completed his secondary education at the Colegio Nacional de Buenos Aires.

Aizenberg began his career as an architect, but left it to devote himself to painting. He became a student of Antonio Berni, and from 1950 to 1953 studied with the surrealist Juan Batlle Planas, an unclassifiable artist who emphasized the importance of surrealism and psychoanalysis.[2]

Career

His first solo exhibition, in 1958, was at the Galeria Galatea. It was followed by six other solo exhibitions before the 1969 Torcuato di Tella Institute major retrospective of his work which included collages, sculptures, 50 paintings, and 200 drawings.[2] His work was included in numerous group exhibitions, including the 1963 São Paulo Bienal. His first European exhibit was in 1972 at London's Hanover Gallery.[2] The following year, he exhibited at Gimpel and Hanover Gallery in Zürich, Switzerland. In 1982, his work was exhibited at Milan's Naviglio Gallery.

During the period 1985–1986 and again in 1993, he taught painting at the Instituto Universitario Nacional del Arte. In 1986, he held a seminar on the Jewish Community.

Works

According to the painter Giorgio de Chirico, Aizenberg admired architecture and the idea of its construction, especially the architecture of the Renaissance. His work is permanently influenced by this fascination.[3] His work shows isolated towers, empty towns, mysterious and uninhabited buildings, and rare polyhedral constructions.

He used slow drying oils to perfect his finishes.

Aizenberg criticized the use of models in teaching art. For him, the model involved a "completely rigid, anachronistic, totalitarian, in the sense of dependence on the artist to model, to the authority of the model, in the teaching of art." He felt that the model was the opposite of free expression, arguing that the essence of modern art was the absence of a model to copy or an external reality that should be imitated.

Much of his work is displayed at the Fortabat Art Collection Museum.

Personal life

Aizenberg married the journalist and writer Matilde Herrera (1931–1990) of the weekly Primera Plana. Her three children from a prior marriage, Valeria, José and Martín Beláustegui, lived with them. After the military coup occurred that led to the dictatorship known as the National Reorganization Process in 1976 and 1977, the three children and their spouses were kidnapped. Herrera's daughter and one of the daughters-in-law were pregnant. All remain missing.[4][5]

In forced exile, Aizenberg moved to Paris in 1977, and in 1981, to Tarquinia, Italy.[2] He returned to Argentina three years later and died in Buenos Aires in 1996 while preparing a retrospective of his work at the National Museum of Fine Arts.

Awards

- Automóvil Club Argentino

- Acquarone Prize, 1962[2]

- First prize, painting, Instituto de Tella, 1963

- Cassandra Foundation Prize, Chicago, 1970[6]

References

- Bethell, Leslie (1998). A cultural history of Latin America: literature, music, and the visual arts in the 19th and 20th centuries. Cambridge University Press. pp. 439. ISBN 0-521-62626-9.

roberto aizenberg.

- Ades, Dawn; Guy Brett; Stanton Loomis Catlin; Rosemary O'Neill (1989). Dawn Ades (ed.). Art in Latin America: the modern era, 1820–1980. Art - Latin American Studies. Yale University Press. pp. 338. ISBN 0-300-04561-1.

Cassandra Foundation .aizenberg.

- "La pintura metafísica de Roberto Aizenberg". todoarquitectura.com (in Spanish). July 8, 2003. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- Ross, Kathleen; Yvette E. Miller (1991). Scents of wood and silence: short stories by Latin American women writers (Digitized Apr 4, 2008 ed.). Latin American Literary Review Press. p. 106.

- "Fact Sheet: Disappearance of a Family, Argentina". desclasificados.com.ar. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- Balderston, Daniel; Mike González; Ana M. López (2000). Encyclopedia of contemporary Latin American and Caribbean cultures. 3. CRC Press. pp. 47–48. ISBN 0-415-22971-5.

Sources

- Barbarito, Carlos (2001). Roberto Aizenberg. Diálogos con Carlos Barbarito. Buenos Aires: Fundación Federico Jorge Klemm.

- Verlichak, Victoria (2007). Aizenberg. ISBN 987-21175-4-3.