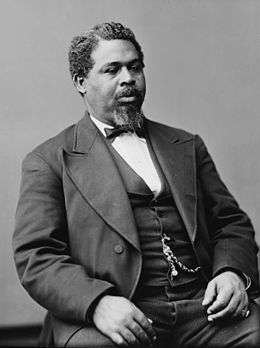

Robert Smalls

Robert Smalls (April 5, 1839 – February 23, 1915) was an American politician, publisher, and businessman. Born into slavery in Beaufort, South Carolina, he freed himself, his crew, and their families during the American Civil War by commandeering a Confederate transport ship, CSS Planter, in Charleston harbor, on May 13, 1862, and sailing it from Confederate-controlled waters of the harbor to the U.S. blockade that surrounded it. He then piloted the ship to the Union-controlled enclave in Beaufort-Port Royal-Hilton Head area, where it became a Union warship. His example and persuasion helped convince President Abraham Lincoln to accept African-American soldiers into the Union Army.

Robert Smalls | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from South Carolina's 7th district | |

| In office March 18, 1884 – March 3, 1887 | |

| Preceded by | Edmund W. M. Mackey |

| Succeeded by | William Elliott |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from South Carolina's 5th district | |

| In office July 19, 1882 – March 3, 1883 | |

| Preceded by | George D. Tillman |

| Succeeded by | John J. Hemphill |

| In office March 4, 1875 – March 3, 1879 | |

| Preceded by | District re-established John D. Ashmore before district eliminated after 1860 |

| Succeeded by | George D. Tillman |

| Member of the South Carolina Senate from Beaufort County | |

| In office November 22, 1870 – March 4, 1875 | |

| Preceded by | Jonathan Jasper Wright |

| Succeeded by | Samuel Greene |

| Member of the South Carolina House of Representatives from Beaufort County | |

| In office November 24, 1868 – November 22, 1870 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | April 5, 1839 Beaufort, South Carolina |

| Died | February 23, 1915 (aged 75) Beaufort, South Carolina |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Hannah Jones

( m. 1856; died 1883)Annie Wigg

( m. 1890; died 1895) |

| Children | 4 |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Branch/service | U.S. Navy and U.S. Army |

| Years of service | 1862–1868 |

| Rank | None (civilian pilot and armed transport captain) |

| Battles/wars | Blockade of Charleston

17 battles including Sherman's March to the Sea |

After the American Civil War he returned to Beaufort and became a politician, winning election as a Republican to the South Carolina State legislature and the United States House of Representatives during the Reconstruction era. Smalls authored state legislation providing for South Carolina to have the first free and compulsory public school system in the United States. He founded the Republican Party of South Carolina. Smalls was the last Republican to represent South Carolina's 5th congressional district until 2010.

Early life

Robert Smalls was born in 1839 to Lydia Polite, a woman enslaved by Henry McKee, who was most likely Smalls' father.[1] She gave birth to him in a cabin behind McKee's house, at 511 Prince Street in Beaufort, South Carolina.[2] He grew up in the city under the influence of the Lowcountry Gullah culture of his mother. His mother lived as a servant in the house but grew up in the fields. Robert was favored over other slaves, so his mother worried that he might grow up not understanding the plight of field slaves, and asked for him to be made to work in the fields and to witness whipping.[3]

When he was 12, at the request of his mother, Smalls' master sent him to Charleston to hire out as a laborer for one dollar a week, with the rest of the wage being paid to his master. The youth first worked in a hotel, then became a lamplighter on Charleston's streets. In his teen years, his love of the sea led him to find work on Charleston's docks and wharves. Smalls worked as a longshoreman, a rigger, a sail maker, and eventually worked his way up to become a wheelman, more or less a pilot, though slaves were not permitted that title. As a result, he was very knowledgeable about Charleston harbor.[4]

At age 17, Smalls married Hannah Jones, an enslaved hotel maid, in Charleston on December 24, 1856. She was five years his senior and already had two daughters. Their own first child, Elizabeth Lydia Smalls, was born in February 1858. Three years later they had a son, Robert Jr., who later died at age two.[5] Robert aimed to pay for their freedom by purchasing them outright, but the price was steep, $800 (equivalent to $22,764 in 2019). He had managed to save up only $100. It could take decades for him to reach $800.[3]

Civil war

Escape from slavery

In April 1861, the American Civil War began with the Battle of Fort Sumter in nearby Charleston Harbor. In the fall of 1861, Smalls was assigned to steer the CSS Planter, a lightly armed Confederate military transport under the command of Charleston's District Commander Brigadier General Roswell S. Ripley.[lower-alpha 1][3] Planter's duties were to deliver dispatches, troops and supplies, to survey waterways, and to lay mines. Smalls piloted the Planter throughout Charleston harbor and beyond, on area rivers and along the South Carolina, Georgia and Florida coasts.[6][7] From Charleston harbor, Smalls and the Planter's crew could see the line of federal blockade ships in the outer harbor, seven miles away.[8] Smalls appeared content and had the confidence of the Planter's crew and owners, and at some time in April 1862, Smalls began to plan an escape. He discussed the matter with the other slaves in the crew except one, whom he did not trust.[2]

On May 12, 1862, the Planter traveled ten miles southwest of Charleston to stop at Coles Island, a Confederate post on the Stono River that was being dismantled.[9] There the ship picked up four large guns to transport to a fort in Charleston harbor. Back in Charleston, the crew loaded 200 lb (91 kg) of ammunition and 20 cord (72 m3) of firewood onto the Planter.[6] At some point, family members[lower-alpha 2] hid aboard another steamer[lower-alpha 3] docked at the North Atlantic wharf.[10][11]

On the evening of May 12, the Planter was docked as usual at the wharf below General Ripley's headquarters.[2] Its three white officers disembarked to spend the night ashore, leaving Smalls and the crew on board, "as was their custom."[12] (Afterward, the three Confederate officers were court-martialed and two convicted, but the verdicts were later overturned.[2]) At about 3 a.m. May 13, Smalls and seven of the eight slave crewmen made their previously planned escape to the Union blockade ships. Smalls put on the captain's uniform and wore a straw hat similar to the captain's. He sailed the Planter past what was then called Southern Wharf and stopped at another wharf to pick up his wife and children and the families of other crewmen.

Smalls guided the ship past the five Confederate harbor forts without incident, as he gave the correct signals at checkpoints. The Planter had been commanded by a Captain Charles C. J. Relyea and Smalls copied Relyea's manners and straw hat on deck to fool Confederate onlookers from shore and the forts.[13] The Planter sailed past Fort Sumter at about 4:30 a.m. The alarm was only raised after the ship was beyond gun range. Smalls headed straight for the Union Navy fleet, replacing the rebel flags with a white bed sheet which was brought by his wife. The Planter had been seen by the USS Onward, which was about to fire until a crewman spotted the white flag.[4] In the dark, the sheet was difficult to see, but the sunrise arrived which allowed viewing.[3]

Witness account:

Just as No. 3 port gun was being elevated, someone cried out, "I see something that looks like a white flag"; and true enough there was something flying on the steamer that would have been white by application of soap and water. As she neared us, we looked in vain for the face of a white man. When they discovered that we would not fire on them, there was a rush of contrabands out on her deck, some dancing, some singing, whistling, jumping; and others stood looking towards Fort Sumter, and muttering all sorts of maledictions against it, and "de heart of de Souf," generally. As the steamer came near, and under the stern of the Onward, one of the Colored men stepped forward, and taking off his hat, shouted, "Good morning, sir! I've brought you some of the old United States guns, sir!" That man was Robert Smalls.[3]

The Onward's captain, John Frederick Nickels,[13] boarded the Planter, and Smalls asked for a United States flag to display. He surrendered the Planter and its cargo to the United States Navy.[4] Smalls' escape plan had succeeded.

The Planter and description of Smalls' actions were forwarded by Lt. Nickels to his commander, Capt. E.G. Parrott. In addition to its own light guns, Planter carried the four loose artillery pieces from Coles Island and the 200 pounds of ammunition. Most valuable, however, were the captain's code book containing the Confederate signals and a map of the mines and torpedoes that had been laid in Charleston's harbor. Smalls' own extensive knowledge of the Charleston region's waterways and military configurations proved highly valuable. Parrott again forwarded the Planter to flag officer Du Pont at Port Royal, describing Smalls as very intelligent. Smalls gave detailed information about Charleston's defenses to Du Pont, commander of the blockading fleet. Federal officers were surprised to learn from Smalls that contrary to their calculations, only a few thousand troops remained to protect the area, the rest having been sent to Tennessee and Virginia. They also learned that the Coles Island fortifications on Charleston's southern flank were being abandoned and were without protection.[6] This intelligence allowed Union forces to capture Coles Island and its string of batteries without a fight on May 20, a week after Smalls' escape. The Union would hold the Stono inlet as a base for the remaining three years of the war.[2] Du Pont was impressed, and wrote the following to the Navy secretary in Washington: "Robert, the intelligent slave and pilot of the boat, who performed this bold feat so skillfully, informed me of [the capture of the Sumter gun], presuming it would be a matter of interest." He "is superior to any who have come into our lines — intelligent as many of them have been."[3]

Service to the Union

Smalls, having just turned 23, quickly became known in the North as a hero for his daring exploit. Newspapers and magazines reported his actions. The U.S. Congress passed a bill awarding Smalls and his crewmen the prize money for the Planter (valuable not only for its guns but low draft in Charleston bay); Southern newspapers demanded harsh discipline for the Confederate officers whose joint shore leave had allowed the slaves to steal the boat.[14] Smalls's share of the prize money came to US$1,500 (equivalent to $38,415 in 2019). Immediately after the capture, Smalls was invited to travel to New York to help raise money for ex-slaves, but Admiral DuPont vetoed the proposal and Smalls began to serve the Union Navy, especially with his detailed knowledge of mines laid near Charleston. However, with the encouragement of Major General David Hunter, the Union commander at Port Royal, Smalls went to Washington, D.C., in August 1862 with Rev. Mansfield French, a Methodist minister who had helped found Wilberforce University in Ohio and had been sent by the American Missionary Association to help former slaves at Port Royal.[15] They wanted to persuade Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to permit black men to fight for the Union. Although Lincoln had previously rescinded orders by Hunter and Generals Fremont and Sherman to mobilize black troops,[15] Stanton soon signed an order permitting up to 5,000 African Americans to enlist in the Union forces at Port Royal. Those who did were organized as the 1st and 2nd South Carolina Regiments (Colored). Smalls worked as a civilian with the Navy until March 1863, when he was transferred to the Army. By his own account, Smalls was present at 17 major battles and engagements in the Civil War.[2]

After capture, the Planter required some repairs, which were performed locally, and went into Union service near Fort Pulaski. The boat was valued for its shallow draft, compared to other boats in the fleet.[16] Smalls was made pilot of the Crusader under Captain Alexander Rhind. In June of that year, Smalls was piloting the Crusader on Edisto in Wadmalaw Sound when the Planter returned to service, and an infantry regiment engaged in the Battle of Simmon's Bluff at the head of the Edisto River. He continued to pilot the Crusader and the Planter. As a slave, he had assisted in laying mines (then called "torpedoes") along the coast and river. Now, as a pilot, he helped find and remove them and serviced the blockade between Charleston and Beaufort. He was also present when the Planter was fired upon at several fights at Adam's Run on the Dawho River and at battles at Rockville, at John's Island, and at the Second Battle of Pocotaligo.[13]

He was made pilot of the ironclad USS Keokuk, again under captain Rhind, and took part in the attack on Fort Sumter on April 7, 1863, which was a preamble to the Second Battle of Fort Sumter later that fall. The Keokuk took 96 hits and retired for the night, sinking the next morning. Smalls and much of the crew moved to the Ironside and the fleet returned to Hilton Head.[13]

In June 1863, David Hunter was replaced as commander of the Department of the South by Quincy Adams Gillmore. With Gillmore's arrival, Smalls was transferred to the quartermaster's department. Smalls was pilot of the USS Isaac Smith, later recommissioned in the Confederate Navy the Stono in the expedition on Morris Island. When Union troops took the south end of the Island, Smalls was put in charge of the Light House Inlet as pilot.[13]

On December 1, 1863, Smalls was piloting the Planter under Captain James Nickerson on Folly Island Creek when Confederate batteries at Secessionville opened. Nickerson fled the pilot house for the coal-bunker. Smalls refused to surrender, fearing that the black crewmen would not be treated as prisoners of war and might be summarily killed. Smalls entered the pilothouse and took command of the boat and piloted it to safety. For this, he was reportedly promoted by Gillmore to the rank of captain and made acting captain of the Planter.[13][4]

In May 1864, he was voted an unofficial delegate to the Republican National Convention in Baltimore. Later that spring, Smalls piloted the Planter to Philadelphia for an overhaul. In Philadelphia, he supported what was known as the Port Royal Experiment, an effort to raise money to support the education and development of ex-slaves. At the outset of the Civil War, Smalls could not read or write, but he achieved literacy in Philadelphia. In 1864, Smalls was in a streetcar in Philadelphia and was ordered to give his seat to a white passenger. Rather than ride on the open overflow platform, Smalls left the car. This incident of humiliating a heroic veteran was cited in the debate that resulted in the legislature's passing a bill to integrate public transportation in Pennsylvania in 1867.[2]

In December 1864, Smalls and the Planter moved to support William T. Sherman's army in Savannah, Georgia, at the destination point of his March to the Sea. Smalls returned with the Planter to Charleston harbor in April 1865 for the ceremonial raising of the American flag again at Fort Sumter.[2] Smalls was discharged on June 11, 1865. Other vessels Smalls piloted during the war include the Huron and the Paul Jones.[17] He continued to pilot the Planter, serving a humanitarian mission of taking food and supplies to freedmen who lost their homes and livelihoods during the war. On September 30, the Planter entered the service of the Freedmen's Bureau.[18]

Commission and prize money

Smalls' position in the Union Army and Navy has been disputed and Smalls' reward for the capture of the Planter has been criticized. During Smalls' life, articles about Smalls state that when he was assigned to pilot the Planter, the Navy did not allow him to hold the rank of pilot because he was not a graduate of a naval academy, a requirement at that time. To assure he received proper pay for a captain, he was commissioned second lieutenant of the 1st South Carolina Volunteers (later re-designated as the 33rd US Colored Infantry) and detailed to act as pilot. Many sources also state that General Gillmore promoted Smalls to captain in December 1863 when he saved the Planter when it was under attack near Secessionville.[19] Later sources state that Smalls did receive a commission either in the Army or the Navy, but he was likely officially a civilian throughout the war.[2]

Later in his life, when Smalls sought a Navy pension, he learned that he had not been officially commissioned. He claimed he had received an official commission from Gillmore but had lost it. In 1883, a bill passed committee to put him on the Navy retired list, but in the end was halted, allegedly due to Smalls' being black.[20] In 1897, a special act of congress granted Smalls a pension of $30 per month, equal to the pension for a Navy captain.[2]

In 1883, during discussion of the bill to put Smalls on the Navy retired list, a report stated that the 1862 appraisal of the Planter was "absurdly low" and that a fair valuation would have been over $60,000. However, Smalls received no further payment until 1900. That year, Congress passed a statute paying Smalls $5,000 less the amount paid to him in 1862 ($1,500) for his capture of the steamship. Many still felt that this was less than his due.[2]

After the Civil War

Immediately following the war, Smalls returned to his native Beaufort, where he purchased his former master's house at 511 Prince St, which Union tax authorities had seized in 1863 for refusal to pay taxes. Later, the former owner sued to regain the property, but Smalls retained ownership in the court case. The case became an important precedent in other, similar cases.[2] His mother, Lydia, lived with him for the remainder of her life. He allowed his former master's wife, the elderly Jane Bond McKee, to move into her former home prior to her death. Smalls spent nine months learning to read and write. He purchased a two-story Beaumont building to use as a school for African-American children.[18]

Business ventures

In 1866 Smalls went into business in Beaufort with Richard Howell Gleaves, a businessman from Philadelphia. They opened a store to serve the needs of freedmen. Smalls also hired a teacher to help him study.[17] That April, the Radical Republicans who controlled Congress overrode President Andrew Johnson's vetoes and passed a Civil Rights Act. In 1868, they passed the 14th Amendment, which was ratified by the states to extend full citizenship to all Americans regardless of race.

Smalls invested significantly in the economic development of the Charleston-Beaufort region. In 1870, in anticipation of a Reconstruction-based prosperity, Smalls, with fellow representatives Joseph Rainey, Alonzo Ransier and others, formed the Enterprise Railroad, an 18-mile horse-drawn railway line that carried cargo and passengers between the Charleston wharves and inland depots.[lower-alpha 4][21] Except for one white director ("Carpetbagger" newspaper editor legislator and county treasurer Timothy Hurley), the railroad's board of directors was entirely African American.[22] Richard H. Cain was its first president. Author Bernard E. Powers describes it as "the most impressive commercial venture by members of Charleston's black elite."[23][24] He owned and helped publish a black-owned newspaper, the Beaufort Southern Standard starting in 1872.[18]

Political career

Small's wartime fame and his fluency with the Gullah dialect gave him an avenue for political advancement.[17]

Political affiliation

Smalls was a loyal Republican, which, at the time, dominated the Northern States and passed laws that granted protections for African Americans, whereas the Democrats, who dominated the South, opposed these measures.[25] After the Civil War, Republicans passed laws that granted protections for African Americans and advanced social justice; again, Democrats largely opposed these expansions of power. On August 22, 1912, he wrote to U.S. Senator Knute Nelson, "I never lose sight of the fact that had it not been for the Republican Party, I never would have been an office-holder of any kind—from 1862 to the present."[26] In words that became famous, he described his party as "the party of Lincoln...which unshackled the necks of four million human beings." He wrote this line on September 12, 1912, in a letter expressing his anxiety over the looming presidential election.[27] He concluded that letter, "I ask that every colored man in the North who has a vote to cast would cast that vote for the regular Republican Party and thus bury the Democratic Party so deep that there will not be seen even a bubble coming from the spot where the burial took place."[28]

State politics

Smalls was a delegate at the 1868 South Carolina Constitutional Convention where he was a part of the effort to make free, compulsory schooling available to all South Carolina children.[18] He also served as a delegate at several Republican National Conventions; he also participated in the South Carolina Republican State conventions.

In 1868, Smalls was elected to the South Carolina House of Representatives. He was very effective, and introduced the Homestead Act and introduced and worked to pass the Civil Rights bill. In 1870, Jonathan Jasper Wright was elected judge of the South Carolina Supreme Court and Smalls was elected to fill his unexpired time in the Senate. He continued in the Senate, winning the 1872 election against W. J. Whipper. In the senate he was considered a very good speaker and debater. He was on the Finance Committee and chairman of the Public Printing Committee.[29][18]

He was a delegate to the National Republican Conventions in 1872 in Philadelphia, which nominated Grant for president; in 1876 in Cincinnati, which nominated Hayes; and in 1884 in Chicago, which nominated Blaine[29]—and then continuously to all conventions until 1896.[30] He was also elected vice-president of the South Carolina Republican Party at their 1872 state convention.

In 1873, he was appointed lieutenant-colonel of the Third Regiment, South Carolina State Militia. He was later promoted to brigadier-general of the Second Brigade, South Carolina Militia, and the major-general of the Second Division, South Carolina State Militia. He held this position until 1877, when Democrats took control of the state government.[29][18]

National politics

In 1874, Smalls was elected to the United States House of Representatives, where he served two terms from 1875 to 1879. From 1882 to 1883, he represented South Carolina's 5th congressional district in the House. The state legislature gerrymandered to change the district boundaries, including Beaufort and other heavily black, coastal areas in South Carolina's 7th congressional district, giving the others substantial white majorities. Smalls was elected from the 7th district and served from 1884 to 1887. He was a member of the 44th, 45th, 47th, 48th, 49th U.S. Congresses.[2]

In 1875, he opposed the transfer of troops out of the South, fearing the effect of such a move on the safety of blacks in the South.[17] During consideration of a bill to reduce and restructure the United States Army, Smalls introduced an amendment that "Hereafter in the enlistment of men in the Army...no distinction whatsoever shall be made on account of race or color." However, the amendment was not considered by Congress. He was the last Republican elected from the 5th district until 2010 when Mick Mulvaney took office. He was the second-longest serving African-American member of Congress (behind his contemporary Joseph Rainey) until the mid-20th century.[2]

After the Compromise of 1877, the U.S. government withdrew its remaining forces from South Carolina and other Southern states. Conservative Southern Bourbon Democrats, who called themselves the Redeemers, had resorted to violence and election fraud to regain control of the state legislature. As part of wide-ranging white efforts to reduce African-American political power, Smalls was charged and convicted of taking a bribe five years earlier in connection with the awarding of a printing contract. He was pardoned as part of an agreement by which charges were also dropped against Democrats accused of election fraud.[30]

The scandal took a political toll, and he was defeated by Democrat George D. Tillman in 1878, and again, narrowly, in 1880. He successfully contested the 1880 result and regained the seat in 1882. In 1884, he was elected to fill a seat in a different district. He was nominated for Senate but defeated by Wade Hampton in 1886. During this period in Congress he supported racial integration legislation, supported a pension for the widow of his former Major General, David Hunter, and advised South Carolina blacks to refrain from emigrating to the North and Midwest or to Liberia.[17]

In 1890, he was appointed by President Benjamin Harrison as collector of the Port of Beaufort, which he held until 1913 except during Democrat Grover Cleveland's second term.[2] Smalls was active into the twentieth century. He was a delegate to the 1895 South Carolina constitutional convention. Together with five other black politicians, he strongly opposed white Democratic efforts that year to disfranchise black citizens. They wrote an article for the New York World to publicize the issues, but the state constitution was ratified. It and similar constitutions across the South for some time passed challenges that reached the US Supreme Court, resulting in the exclusion of African Americans from politics across the South and crippling of the Republican Party in the region.

In the late 1890s, he began to suffer from diabetes. He turned down an offer of a colonelcy of a black regiment in the Spanish-American War and to the post of minister to Liberia.

Local politics

Though Smalls was not officially involved with politics on the local level, he had some influence. In 1913, in one of his final actions as community leader, he played an important role in stopping a lynch mob from killing two black suspects in the murder of a white man. He pressured the mayor, saying that blacks he had sent throughout the city would burn the town down if the mob was not stopped. The mayor and sheriff stopped the mob.[17]

Family

With his first wife Hannah Jones Smalls, whom he married on December 24, 1856, Robert Smalls had three children: Elizabeth Lydia (1858–1959; m. Samuel Jones Bampfield, nine living children); Robert Jr. (1861–1863), who died at the age of two; and Sarah Voorhies (1863–1920, m. Dr. Jay Williams, no children). Hannah Jones Smalls had two daughters before she met and married Robert Smalls: Charlotte Jones (m. Willie Williams) and Clara Jones (m. James Rider).[5] Smalls and his family were affiliated with the Baptist Church and attended Berean Baptist Church when living in Washington, D.C.[29] Smalls was a Prince Hall mason as a member of Sons of Beaufort Lodge #36.

Hannah Smalls died on July 28, 1883. On April 9, 1890, Robert Smalls married Annie E. Wigg, a Charleston schoolteacher, who bore him one son, William Robert Smalls (1892–1970). Annie Smalls died on November 5, 1895.[31]

Smalls died of malaria and diabetes in 1915 at the age of 75.[18] He was buried in his family's plot in the churchyard of the Tabernacle Baptist Church in downtown Beaufort. The monument to Smalls in this churchyard is inscribed with a statement he made to the South Carolina legislature in 1895: "My race needs no special defense, for the past history of them in this country proves them to be the equal of any people anywhere. All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life."[32][33]

Honors and legacy

- Fort Robert Smalls was named in his honor; it was built by free blacks in 1863 on McGuire's Hill on the South Side of Pittsburgh during the American Civil War. It survived until the 1940s.[34]

- The Robert Smalls House in Beaufort, South Carolina, has been designated a National Historic Landmark.

- A monument and statue are dedicated to his memory where he is interred at Tabernacle Baptist Church in Beaufort.[35]

- The Robert Smalls School in Cheraw, South Carolina, is named for him.

- Robert Smalls Middle School in Beaufort County, South Carolina, is named for him.

- During World War II, Camp Robert Smalls was established as a sub-facility of the Great Lakes Naval Training Center to train black sailors (the Navy was segregated in those years).[36]

- The Verdier House museum in Beaufort has an exhibit on Robert Smalls.[37]

- In 2004, the US named a ship for Robert Smalls, the USAV Major General Robert Smalls (LSV-8), a Kuroda-class logistics support vessel operated by the U.S. Army. It is the first Army ship named after an African American.[38]

- Charleston held commemorative ceremonies in 2012 on the 150th anniversary of Robert Smalls' escape on the Planter, with special programs on May 12 and 13.[39]

- Robert Smalls Parkway is a five-mile section of South Carolina Highway 170 that crosses Port Royal Island and leads into Beaufort.[40]

- A statue of Robert Smalls is in the US National Museum of African American History and Culture.[41]

- An image of Robert Smalls is featured on the cover of the album Devil Is Fine by the musical project Zeal & Ardor.[42]

- There is a proposal to create a statue of Robert Smalls to be installed at the South Carolina State House.[43]

See also

- List of African-American United States Representatives

- List of slaves

Notes

- The 147-foot Planter was "a 'first-class coastwise steamer' hewn locally for the cotton trade out of 'live oak and red cedar'".

- These family members were: Smalls' wife Hannah, their two children Elizabeth Lydia and Robert Jr., and Hannah's daughter Clara; Susan Smalls, the wife of another crewman; their child, and Susan's sister; and two other women, Annie White and Lavinia Wilson.

- This steamer's name has been spelled Etowah, Etwan, Etiwan, Etowan and Hetiwan.

- Its route was planned to run along the wharves from White Point Garden in the Battery north along East Bay Street to Calhoun Street and into the city, northwest to "Ten Mile Hill," near where the airport is today.

References

- "Robert Smalls :: A Traveling Exhibition". www.robertsmalls.com. Archived from the original on September 25, 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- Westwood, Howard (1991). Black Troops, White Commanders and Freedmen During the Civil War. SIU Press. pp. 74–85.

- Gates, Henry Louis Jr. "Which Slave Sailed Himself to Freedom?". pbs.org. PBS. Retrieved August 19, 2018.

- Henig, Gerald (March 2007). "The Unbeatable Mr. Smalls". history.net. America's Civil War.

- "Robert Smalls" (PDF). Civil War Figures As Examples of Character and Leadership. Civil War Preservation Trust. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 8, 2016.

- Patrick Brennan (1996). Secessionville: Assault on Charleston. Savas Pub. pp. 25–27. ISBN 978-1-882810-08-6.

- Smalls piloted an expedition to survey all the sandbars "on the coast of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida". Charles Cowley (1882). The Romance of History in "the Black County,": And the Romance of War in the Career of Gen. Robert Smalls, "the Hero of the Planter.". p. 9.

- "Robert's Daring Voyage to Freedom". robertsmalls.com. The Robert Smalls Collection. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- Hagood, Johnson (1910). Brooks, U R (ed.). Memoirs of the War of Secession. Columbia, SC: State Company. pp. 52–62.

- Billingsley, Andrew (2007). Yearning to Breathe Free: Robert Smalls of South Carolina and His Families. University of South Carolina Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-57003-686-6.

- "Etwan". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Retrieved June 12, 2016 – via hazegray.org/danfs/.

- Hagood, Johnson (1910). Brooks, U R (ed.). Memoirs of the War of Secession. Columbia, SC: State Company. p. 78.

- Dezendorf, John F. (1887). "Report to accompany bill, H. R. 7059, January 23, 1883". In Simmons, William J.; McNeal Turner, Henry (eds.). Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising. G. M. Rewell & Company. pp. 165–179. ISBN 978-1-4680-9681-1.

- Philip Dray, Capitol Men (Houghton Mifflin Company 2008), p. 9.

- Dray, p. 13.

- Elwell, J. J. (1887). "Letter to District Quartermaster, September 10, 1862". In Simmons, William J.; McNeal Turner, Henry (eds.). Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising. G. M. Rewell & Company. pp. 165–179. ISBN 978-1-4680-9681-1.

- Turkel, Stanley. Heroes of the American Reconstruction: Profiles of Sixteen Educators, Politicians and Activists. McFarland, 2005.

- Reef, Catherine. African Americans in the Military. Infobase Publishing, May 14, 2014, pp. 184–186.

- "Gen. Robert Smalls". National Republican. Washington, DC. March 6, 1886. p. 3. Retrieved August 30, 2016 – via newspapers.com.

- "A Republican Color Line". Pittsburgh Daily Post. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. February 9, 1883. p. 2. Retrieved August 31, 2016 – via newspapers.com.

- Acts and Joint Resolutions of the General Assembly of the State of South Carolina. State Printer. 1870. p. 391.; "1886 Charleston Earthquake, Fig. 28B". eas.slu.edu. Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Saint Louis University. Retrieved June 19, 2016.

- Powers, p. 169.

- By the mid-1870s, the railroad had passed into new, mostly white ownership. It survived into the 1890s. Powers Jr., Bernard E. (1994). Black Charlestonians: A Social History, 1822–1885. Fayetteville, Arkansas: University of Arkansas Press. pp. 169–70. ISBN 1-55728-583-7.; Goodsell, Charles M.; Wallace, Henry E. (1893). The Manual of Statistics: Stock Exchange Hand-book ... p. 441.

- Radio presentation, "Enterprise Railroad." mp3 format. "South Carolina from A to Z Archive (2011-2014)". scetv.org. South Carolina Public Radio. December 26, 2013. Retrieved June 19, 2016.

- Wolchover, Natalie (2012) Why Did the Democratic and Republican Parties Switch Platforms?.

- Yellin, Eric Steven (2007). Racism in the Nation's Service: Government Workers and the Color Line in Woodrow Wilson's America. UNC Press Books. ISBN 978-1-4696-0720-7. p. 77.

- Yellin, pp. 76-77.

- Newkirk, Pamela (2009). Letters from Black America. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-1-4299-3483-1. pp. 123–4.

- Simmons, William J., and Henry McNeal Turner. Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising. GM Rewell & Company, 1887. pp 165–179.

- Foner, Eric ed., Freedom's Lawmakers: A Directory of Black Officeholders During Reconstruction Revised Edition. (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1996). ISBN 0-8071-2082-0. p. 198.

- Billingsley, p. 213.

- "Robert Smalls – Tabernacle Baptist Church – Beaufort, S.C." waymarking.com. January 18, 2014. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- Journal of the Constitutional Convention of the State of South Carolina. C. A. Calvo, jr., State Printer. 1895. p. 476. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- "Greater Pittsburgh Area". North American Forts. Retrieved July 4, 2008.

- "Resting Place of Robert Smalls/Tabernacle Baptist Church". Visit Beaufort. Beaufort Visitors Center. Retrieved June 21, 2020.

- MacGregor, Morris J. (December 1981). Integration of the Armed Forces, 1940–1965. Government Printing Office. pp. 67ff. ISBN 978-0-16-001925-8. Retrieved September 13, 2011.

- "Verdier house". Historic Beaufort Foundation. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

- "Latest Army Vessel Honors Black American Hero". army.mil. U.S. Army. Retrieved May 23, 2016.

- Hicks, Brian (May 7, 2012). "Remembering a hero, statesman Weekend is 150th anniversary of daring voyage". Post and Courier. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

- Google (May 11, 2018). "SC-170 & Robert Smalls Pkwy, Beaufort, S.C. 29906S" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

- Gangitano, Alex (September 15, 2016). "Museum of African American History Reveals History and Vision". Roll Call. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

- Dedman, Remfry (February 20, 2017). "American slave and black metal hybrid Zeal & Ardor streams debut album". The Independent. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

- Marchant, Bristow (September 20, 2017). "New SC statue proposed, but fight over Confederate monuments will go on". The State. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

Further reading

- Coker, P. C., III. Charleston's Maritime Heritage, 1670–1865: An Illustrated History. Charleston, S.C.: Coker-Craft, 1987. 314 pp.

- Downing, David C. A South Divided: Portraits of Dissent in the Confederacy, Nashville: Cumberland House, 2007. ISBN 978-1-58182-587-9

- Foner, Eric ed., Freedom's Lawmakers: A Directory of Black Officeholders During Reconstruction Revised Edition. (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1996). ISBN 0-8071-2082-0. Between 1865 and 1876, about 2,000 blacks (including men of color or mixed race) held elective and appointive offices in the South. A few are relatively well-known, but most became obscure because official state histories prepared after Reconstruction omitted them; whites dominated state governments and suppressed the black population and its history. Foner profiles more than 1,500 black legislators, state officials, sheriffs, justices of the peace, and constables in this volume.

- Gabridge, Patrick, Steering to Freedom (Penmore Press, 2015). ISBN 1942756224. Novel about Robert Smalls' life.

- Kennedy, Robert F., Jr. Robert Smalls, the Boat Thief (New York: Hyperion, 2008). ISBN 1-4231-0802-7. A picture book illustrated by Patrick Faricy.

- Rabinowitz, Howard N. Southern Black Leaders of the Reconstruction Era (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1982) ISBN 0-252-00929-0

- Sterling, Dorothy. Captain of the "Planter": The Story of Robert Smalls (Doubleday & Co. Garden City, 1958)

- Thomas, Rhondda R. & Ashton, Susanna, eds (2014). The South Carolina Roots of African American Thought, Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. "Robert Smalls (1839–1915)," pp. 65–70.

- Uya, Okon Edet, From Slavery to Public Service: Robert Smalls, 1839–1915 (Oxford University Press. New York, 1971)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Robert Smalls. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Robert Smalls |

- Q&A interview with Cate Lineberry on her book Be Free or Die: The Amazing Story of Robert Smalls' Escape from Slavery to Union Hero, August 6, 2017, C-SPAN

- Entry from the House of Representatives

- In the episode "Robert Smalls" of the podcast Criminal, published on June 19, 2020, Phoebe Judge tells the story of Robert Smalls.

- United States Congress. "Robert Smalls (id: S000502)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Robert Smalls: Former Slave and Civil War Hero, Hagley Museum and Library

- In the episode "The Wheel" of the podcast The Memory Palace, published on February 10, 2016, Nate DiMeo tells the story of Robert Smalls.

- Robert Smalls at Find a Grave

| U.S. House of Representatives | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by District re-established John D. Ashmore before district eliminated after 1860 |

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from South Carolina's 5th congressional district 1875–79 |

Succeeded by George D. Tillman |

| Preceded by George D. Tillman |

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from South Carolina's 5th congressional district 1882–83 |

Succeeded by John J. Hemphill |

| Preceded by Edmund W. M. Mackey |

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from South Carolina's 7th congressional district 1884–87 |

Succeeded by William Elliott |