Reims Gospel

Reims Gospel (French: Texte du Sacre which means "coronation text"; also referred to in some Czech sources as the Sázava Gospel or Remešský kodex) is an illuminated manuscript of Slavonic (Slavic) origin which became part of the Reims Cathedral treasury. Henry III of France and several of his successors including Louis XIV took their oath on it.[1] In the time of Charles IV, who gave it to the just-founded Emmaus monastery in Prague, the text was believed to have been written by the hand of St. Procopius.

Description

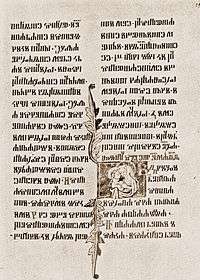

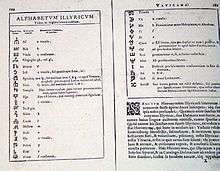

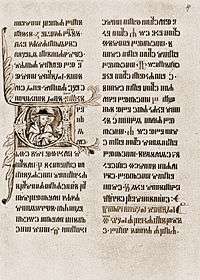

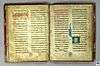

Out of a total of 47 double-sided sheets, 16 sheets are written in Cyrillic (as a fragment) and 31 sheets in the Glagolitic alphabet.[1][2] The book used to have a treasure binding, richly decorated and embellished with gold, precious stones, and relics, among them a fragment of the True Cross.[2] The precious stones and the relics probably disappeared from the book cover during the French Revolution. It features six historiated initials in the Glagolitic part and several ornamental capitals at the start of sections.

Content

The Cyrillic part includes a pericope from 27 October to 1 March following the Greek Catholic rite.[2] The Glagolitic part covers pericopes from Palm Sunday to the Feast of the Annunciation (March 25) following the Roman Catholic rite.[2] In a special postscript a Bohemian monk noted: "The Year of Our Lord 1395. These Gospels and Epistles were written in the Slavic language ... the other part was written by the hand of St. Procopius, abbot, and this text was offered by Charles IV, Emperor of the Romans, to the Slavic monastery, in honor of Saint Jerome and Saint Procopius, God, please give him eternal rest. Amen."[2]

History

The origin of the manuscript is not certain. The older part was probably written in calligraphy on the island of Krk, or in a monastery in Serbia, Bulgaria, Bohemia, Ukraine, or Russia.[1]

It was first recorded in the last half of the 14th century, in the time of Charles IV, who gave it to the just-founded Emmaus monastery in Prague (Czech: Emauzský klášter, Na Slovanech, Emauzy), where the Slavonic liturgy was to be celebrated (the church of the monastery was dedicated to Saints Cyril and Methodius, St. Vojtěch, St. Procopius, and St. Jerome, who was considered to have translated the Gospels from Greek to the Old Slavonic language).[1] The text was believed to have been written by the hand of St. Procopius, abbot of Sázava Monastery. It was probably lost from Prague in the time of the Hussite Wars; after some time (1451[3]) it appeared in Istanbul, where the books by St. Jerome were said to be kept.[2] In 1574, it was bought by Charles, Cardinal of Lorraine (from the Patriarch of Constantinople, whom he knew from the Council of Trent[2]), and donated to Reims Cathedral.[1] Because the book was nicely decorated and it was believed it had been scribed by St. Jerome, the manuscript began to be used in the coronation ceremony of French kings, who took the oath of the Order of the Holy Spirit by touching the book.[1]

In 1717, Russian Tsar Peter the Great visited Reims and, upon seeing the manuscript, noticed the Cyrillic alphabet.[1]

During the French Revolution the manuscript disappeared and was not found until the 1830s, when it was discovered in the Reims library by the city librarian, Louis Paris, after a request by a Slovene linguist Jernej Bartol Kopitar who was an administrator at the Vienna Court Library at that time.[3] Mr. Paris asked a Russian counsellor and archeologist Sergey Stroieff (or Turgenev?[1]) for help with recognizing the text.[2] It was found with neither the gold nor the precious stones in the cover.[1] The discovery brought a revival of interest, especially in Slavic countries. The first facsimile was created by Reims librarian Louis Paris and it was analyzed in detail by Polish paleographer Korwin Jan Jastrzębski (1805–1852).[1] Ustazade Silvestre de Sacy made a lithographic copy of the manuscript and gave it to Russian Tsar Nicholas I.[1] Nicholas then financed another using intaglio printing (1843) and let Jernej Kopitar write his comment arguing that all of the manuscript comes from 14th century.[1] In 1846 Czech philologist Václav Hanka made his edition, which was available to the general public, and received for that act of merit the cross of the Order of St. Anna from the Tsar and a brilliant ring from Austrian Emperor Ferdinand I.[1]

Gallery

- Glagolic part

See also

References

- František Bílý: Od kolébky našeho obrození, Prague 1904, pp. 7–12

- Jacques-Paul Migne: Dictionnaire d'épigraphie Chrétienne, Paris 1852

- Auguste Vallet De Viriville: Bibliothèque de l'école des chartes, Volume 15, 1854, pp.192–194