Rehovot

Rehovot (Hebrew: רְחוֹבוֹת) is a city in the Central District of Israel, about 20 kilometers (12 miles) south of Tel Aviv. In 2018 it had a population of 141,579.[1]

Rehovot

| |

|---|---|

| Hebrew transcription(s) | |

| • ISO 259 | Rḥobot |

Rehovot Science Park | |

| |

Rehovot  Rehovot | |

| Coordinates: 31°53′52.67″N 34°48′29.24″E | |

| Country | |

| District | Central |

| Founded | 1890 |

| Government | |

| • Type | City |

| • Mayor | Rahamim Malul |

| Area | |

| • Total | 23,041 dunams (23.041 km2 or 8.896 sq mi) |

| Population (2018)[1] | |

| • Total | 141,579 |

| • Density | 6,100/km2 (16,000/sq mi) |

| Name meaning | Broad Places[2] |

| Website | www.rehovot.muni.il |

Etymology

Israel Belkind, founder of the Bilu movement, proposed the name "Rehovot" (lit. 'wide expanses') based on Genesis 26:22: "And he called the name of it Rehoboth; and he said: 'For now the Lord hath made room for us, and we shall be fruitful in the land'."[3] This Bible verse is also inscribed in the city's logo. The biblical town of Rehoboth was located in the Negev Desert.[4]

History

Ottoman era

Rehovot was established in 1890 by pioneers of the First Aliyah on the coastal plain near a site called Khirbat Deiran, which now lies in the center of the built-up area of the city.[5]

Excavations at Khirbat Deiran have revealed signs of habitation in the Hellenic and Roman periods and through the Byzantine period, with a major expansion to about 60 dunams during the early centuries of Islamic rule.[5] Evidence of Jewish and possibly Samaritan occupants during the Roman and Byzantine periods has been found.[6] In 1939, Khirbet Deiran was identified by Klein with Kerem Doron ("vineyard of Doron"), a place mentioned in Talmud Yerushalmi (Peah 7:4), but Fischer considers that there is "no special reason" for this identification,[5] while Kalmin is unsure whether Doron was a place or a person.[7]

Rehovot was founded as a moshava in 1890 by Polish Jewish immigrants who had come with the First Aliyah, seeking to establish a township independent of the Baron Edmond James de Rothschild, on land purchased from a Christian Arab by the Menuha Venahala society, an organization in Warsaw that raised funds for Jewish settlement in Eretz Israel.[3][8]

At the time, all of Palestine was part of the Ottoman Empire and the area that became Rehovot, like much of the land in Palestine then, had been settled by Arabs tending animals and living essentially as squatters on land that had been exclusively at their disposition in an economic system where ownership of the land per se had not been a norm. This meant that the land purchase represented a disruption to the livelihoods and lifestyles of those who had viewed it as theirs for generations.[9]

In March 1892, a dispute over pasture rights erupted between the residents of Rehovot and the neighboring village of Zarnuqa, which took two years to resolve. Another dispute broke out with the Suteriya Bedouin tribe, which had been cultivating some of the land as tenant farmers. According to Moshe Smilansky, one of the early settlers of Rehovot, the Bedouins had received compensation for the land, but refused to vacate it. In 1893, they attacked the moshava. Through the intervention of a respected Arab sheikh, a compromise was reached, with the Bedouins receiving an additional sum of money, which they used to dig a well.[10]

In 1890, the region was an uncultivated wasteland with no trees, houses or water.[11] The moshava's houses were initially built along two parallel streets: Yaakov Street and Benjamin Street, before later expanding, and vineyards, almond orchards and citrus groves were planted, but the inhabitants grappled with agricultural failures, plant diseases, and marketing problems.

The first citrus grove was planted by Zalman Minkov in 1904. Minkov's grove, surrounded by a wall, included a guard house, stables, a packing plant, and an irrigation system in which groundwater was pumped from a large well in the inner courtyard. The well was 23 meters deep, the height of an eight-story building, and over six meters in diameter. The water was channeled via an aqueduct to an irrigation pool, and from there to a network of ditches dug around the bases of the trees.[12]

The Great Synagogue of Rehovot was established in 1903, during the First Aliyah period.[13]

In 1908, the Workman's Union (Hapoel Hazair) organized a group of 300 Yemenite immigrants then living in the region of Jerusalem and Jaffa, bringing them to work as farmers in the colonies of Rishon-le-Zion and Rehovot.[14] Only a few dozen Yemenite families had joined Rehovot by 1908.[15] They built houses for themselves in a plot given to them at the south end of the town, which became known as Sha'araim.[15] In 1910, Shmuel Warshawsky, with the secret support of the JNF, was sent to Yemen to recruit more agricultural laborers.[15] Hundreds arrived starting in 1911 and were housed first in a compound one kilometre south of Rehovot and then in a large extension of the Sha'araim quarter.[15]

In 1913, Rehovot became the flashpoint for a dramatic turn in relations among the region's ethnicities: after an itinerant Arab camel driver passing through stole some grapes from a local farm, local Jewish settlers arriving on the scene brutally attacked him, which led to the arrival of Arab reinforcements, then to a skirmish that proved fatal - one death on each side of the gunfire. It is alleged that this was the moment that a previously peaceful co-existence among Jews and Arabs, united under the Ottoman Empire, became overnight an "us vs. them" divisiveness that has prevailed ever since.[9]

In February 1914, Rothschild visited Rehovot during the fourth of his five visits to the Land of Israel.[16] That year, Rehovot had a population of around 955.

British Mandate

In 1920, the Rehovot Railway Station was opened, which greatly boosted the local citrus fruit industry. A few packing houses were built near the station so as to enable the fruit to be sent by railway to the rest of the country and to the port of Jaffa for export to Europe. According to a census conducted in 1922 by the British Mandate authorities, Rehovot had a population of 1,242 inhabitants, consisting of 1,241 Jews and 1 Muslim,[17] increasing in 1931 census to 3,193 inhabitants, in 833 houses.[18] In 1924, the British Army contracted the Palestine Electric Company for wired electric power. The contract allowed the Electric Company to extend the grid beyond the original geographical limits that had been projected by the concession it was given. The high-tension line that exceeded the limits of the original concession ran along some major towns and agricultural settlements, offering extended connections to the Jewish towns of Rishon Le-Zion, Ness Ziona and Rehovot (in spite of their proximity to the high-tension line, the Arab towns of Ramleh and Lydda remained unconnected).[19]

In 1931, the first workers moshav, Kfar Marmorek, was built on lands acquired by the Jewish National Fund in 1926 from the village Zarnuqa, in which ten Yemenite Jewish families evicted from Kinneret in 1931 were resettled to work the land, and later joined by thirty-five other families from Sha'araim. Today, it is a suburb of Rehovot.[20]

The agricultural research station that opened in Rehovot in 1932 became the Department of Agriculture of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. In 1933, a juice factory was built. In 1934, Chaim Weizmann established the Sieff Institute, which later became the Weizmann Institute of Science. In 1937, Weizmann built his home on the land purchased adjacent to the Sieff Institute. The house later served as the presidential residence after Weizmann became president in 1948. Weizmann and his wife are buried on the grounds of the institute.

In 1945, Rehovot had a population of 10,020, and in 1948, it had grown to 12,500. The suburb of Rehovot, Kefar Marmorek, had a population of 500 Jews in 1948.[21]

State of Israel

On 29 February 1948, the Lehi blew up the Cairo to Haifa train shortly after it left Rehovot, killing 29 British soldiers and injuring 35. Lehi said the bombing was in retaliation for the Ben Yehuda Street bombing a week earlier. The Scotsman reported that both Weizmann's home and the Agricultural Institute were damaged in the explosion, although the site was 1–2 miles [1.6–3.2 km] away. On 28 March 1948, Arabs attacked a Jewish convoy near Rehovot.[22] In 1950, Rehovot, which had a population of about 18,000, was declared a city.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1914 | 955 | — |

| 1922 | 1,242[23] | +30.1% |

| 1931 | 3,193[24] | +157.1% |

| 1948 | 12,500 | +291.5% |

| 1955 | 26,000 | +108.0% |

| 1961 | 29,000 | +11.5% |

| 1972 | 39,300 | +35.5% |

| 1983 | 67,900 | +72.8% |

| 1995 | 85,200 | +25.5% |

| 2008 | 111,100 | +30.4% |

| 20151 | 132,700 | +19.4% |

| Source: Israel Central Bureau of Statistics 1 end of year estimate | ||

Between 1914 and 1991, the population rose from 955 to 81,000, and the area of the town more than doubled. Parts of Rehovot's suburbs are built on land that before 1948 belonged to the village of Zarnuqa, population 2,620, including 240 Jews in Gibton.[25] In 1995, there were 337,800 people living in the greater Rehovot area. As of 2007, the ethnic makeup of the city was 99.8% Jewish. There were 49,600 males and 52,300 females, of whom 31.6% were 19 years of age or younger, 16.1% between the ages of 20 and 29, 18.2% between 30 and 44, 18.2% from 45 to 59, 3.5% from 60 to 64, and 12.3% 65 years of age or older. The population growth rate was 1.8%.[26]

In Rehovot, there are three significant Jewish ethnic minorities: Russian Jews, Yemenite Jews, and Ethiopian Jews, concentrated largely in the Kiryat Moshe and Oshiot areas. There is a growing community of religious anglo speaking people who primarily live in Northern Rehovot around the Weizmann Institute of Science.

Education and culture

In 2004, there were 19,794 students and 53 schools in the city: 30 elementary schools with 9,875 students and 29 high schools with 9,919 students.[26] 61.3% of 12th graders graduated with a Bagrut matriculation certificate.

The city is home to the Weizmann Institute of Science, the Faculty of Agriculture of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and the Peres Academic Center College. There are also a number of smaller colleges in Rehovot that provide specialized and technical training. Kaplan Medical Center acts as an ancillary teaching hospital for the Medical School of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

The Minkov Orchard Museum was established in Rehovot with the assistance of the Swiss descendants of Zalma Minkov, whose husband planted the city's first citrus grove.[12]

Economy

As of 2004, there were 41,323 salaried workers and 2,683 self-employed. The mean monthly wage for a salaried worker was ILS 6,732, a real change of −5.2% over the course of the previous year. Salaried males had a mean monthly wage of ILS 8,786 (a real change of −4.8%) versus ILS 4,791 for females (a real change of −5.3%). The mean income for the self-employed was 6,806. There were 1,082 people receiving unemployment benefits and 6,627 people receiving an income guarantee.[26] In 2013, Rehovot had the highest average net monthly income among households in Israel, at NIS 16,800.[27]

Rehovot is home to numerous industrial plants, and has an industrial park in the western part of the city. Among them are the Tnuva dairy plant, the Yafora-Tavori beverage factory, and the Feldman ice cream factory.

The Tamar Science Park, established in 2000, is a high-tech park of 1,000 dunams (1.0 km2) at the northern entrance of the city.[28] The Tamar Science Park adjoins the older Kiryat Weizmann industrial park. Although the entire extended science park is largely conceived as an area of Rehovot, the Kiryat Weizmann part is actually under the municipal boundaries of neighbouring Ness Ziona. Tamar Science Park is home to branches of leading hi-tech and bio-tech companies.

Sports

Rehovot has had three clubs representing it the top division of Israeli football: Maccabi Rehovot between 1949 and 1956, Maccabi Sha'arayim between 1963 and 1969 and again in 1985, and Hapoel Marmorek in the 1972–73 season. and also have club Bnei Yeechalal thy play at Liga Bet South B.

Today Maccabi Sha'arayim is the highest-ranked club, playing in Liga Leumit, the third level. Marmorek play in Liga Alef, the third level; Maccabi Rehovot play in Liga Gimel, the fifth and lowest division.

During the 1980s, some local swimmers excelled, thanks to the local Weissgal Center Water Park.

List of Rehovot men football clubs playing at state level and above:

| Club | Founded | League | Level | Home Ground | Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maccabi Rehovot | 1912 | Liga Gimel Central | 5 | Kiryat Moshe | 500 |

| Hapoel Marmorek | 1949 | Liga Alef South | 3 | Itztoni Stadium | 800 |

| Maccabi Sha'arayim | 1950 | Liga Leumit | 2 | Ness Ziona Stadium | 3,500 |

| Bnei Yeechalal | 2007 | Liga Bet South B | 4 | Kiryat Moshe | 500 |

Twin towns – sister cities

Rehovot is twinned with:

Gallery

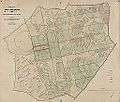

Map of Rehovot in 1897

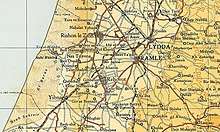

Map of Rehovot in 1897 Rehovot 1945 1:250,000

Rehovot 1945 1:250,000 Rehovot 1948 1:20,000

Rehovot 1948 1:20,000- Rehovot mall and municipality

Particle accelerator at the Weizmann Institute of Science

Particle accelerator at the Weizmann Institute of Science Rehovot campus of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Rehovot campus of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem Rehovot Library

Rehovot Library Hewlett Packard offices in Rehovot

Hewlett Packard offices in Rehovot Yemenite Jewish Heritage Center in Rehovot

Yemenite Jewish Heritage Center in Rehovot

Notable residents

- Nili Abramski, professional long-distance runner

- Dan Almagor, playwright

- Aki Avni, actor, born in Rehovot[36]

- Shawn Dawson (born 1993), Israeli basketball player

- Aryeh Frimer, Bar-Ilan University chemist and rabbi

- Shlomo Glickstein, professional tennis player, born in Rehovot[37]

- Gidi Gov, singer

- Michal Hein (born 1968), Olympic windsurfer

- Tzipi Hotovely, Member of Knesset for Likud[38]

- Eres Holz, composer

- Roi Kahat, professional footballer

- Ephraim Katzir, biophysicist and fourth President of The State of Israel[39]

- Olga Kirsch, South African and Israeli poet

- Yannets Levi, writer

- Nir Levine, professional footballer, director of football youth team on Maccabi Tel Aviv

- Shlomit Malka, model

- Rahamim Malul, Mayor of Rehovot[36]

- Arnon Milchan, Hollywood film producer

- Matan Naor, professional basketball player

- Talia Rahimi, author

- Shmuel Rechtman, Mayor of Rehovot from 1970–79, born in Rehovot[40]

- Sergy Richter (born 1989), Olympic sport shooter and world junior record holder

- Danny Robas, singer

- Zdenka Samish, Czech-Israel food technology researcher, director of the Department of Food Technology at the Agricultural Research Station (Volcani Center)

- Eliezer Sherbatov (born 1991), Canadian-Israeli ice hockey player

- David Tal, four-time member of Knesset and member of the Kadima party[41]

- Israel Tal, an Israel Defense Forces general, designer of Israel's Merkava tank.

- Benjamin Elazari Volcani, microbiologist

- Amir Weintraub, professional tennis player

- Chaim Weizmann, first President of the State of Israel[42]

- S. Yizhar (1916–2006), writer

- Ada Yonath, crystallographer at the Weizmann Institute of Science and first Israeli woman Nobel Prize winner[43]

References

- "Population in the Localities 2018" (XLS). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. 25 August 2019. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- From Genesis 26:22. Word stems from raḥav (רחב), meaning broad.

- Joanna Paraszczuk (12 March 2010). "Rehovot keeps an eye on the past as it looks to the future". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- "The Jewish Agency". The Jewish Agency.

- M. Fischer; I. Taxel; D. Amit (2008). "Rural settlement in the vicinity of Yavneh in the Byzantine period: A religio-archaeological perspective". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 350 (350): 7–35. doi:10.1086/BASOR25609264.

- A. Bouchenino (2007). "Building remains and industrial installations from the early Islamic period at Khirbat deiran, Reḥovot". Atiqot. 56: 119–144, 84*–85*.

- Richard Kalmin (2006). Jewish Babylonia between Persia and Roman Palestine. Oxford University Press. pp. 180, 252.

- O. Efraim; S. Gilboa (2007). "Reḥovot". In Michael Berenbaum; Fred Skolnik (eds.). Encyclopaedia Judaica. 17 (2 ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA.

- "1913: Seeds of Conflict - PBS Programs - PBS". 1913: Seeds of Conflict - PBS Programs - PBS.

- Aryeh L. Avneri (1982). The Claim of Dispossession: Jewish Land-Settlement and the Arabs, 1878-1948. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 9781412836210. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- Aryeh L. Avneri (1982). The Claim of Dispossession: Jewish Land-Settlement and the Arabs, 1878-1948. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 9781412836210. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- Ronit Vered (6 March 2008). "Pure Gold". Haaretz. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- Religious Renewal, Haaretz, 22 November 2019

- Joshua Feldman, The Yemenite Jews, London 1913, p. 23

- Zvi Shilony (1998). Ideology and Settlement; the Jewish National Fund, 1897–1914. Jerusalem: Magnes Press. pp. 303–307.

- Ofer Aderet (9 February 2014). "Rothschild urged Zionists: Work hard, get along with Arab neighbors". Haaretz. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- "Palestine Census ( 1922)" – via Internet Archive.

- Mills, 1932, p. 23

- Shamir, Ronen (2013). Current Flow: The Electrification of Palestine. Stanford University Press.

- Yalqut Teiman, Yosef Tobi and Shalom Seri (editors), Tel-Aviv 2000, p. 130, s.v. כפר מרמורק (Hebrew) ISBN 965-7121-03-5

- Jardine, R.F.; McArthur Davies, B.A. (1948). A Gazetteer of the Place Names which appear in the small-scale Maps of Palestine and Trans-Jordan. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine. p. 49. OCLC 610327173.

- Martin (2005). Routledge Atlas of the Arab-Israeli Conflict. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-35901-5.

- "Palestine Census ( 1922)" – via Internet Archive.

- 1931 census of Palestine, p. 23

- Walid Khalidi (editor). All that Remains: Palestinian villages occupied and depopulated by Israel in 1948. IPS, Washington. 1992. p. 425. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- According to Israel Central Bureau of Statistics data (in Hebrew)

- http://www.globes.co.il/en/article-1000893437

- Lior Dattel; Erez Sherwinter (18 August 2008). "The 'science city' is not sparkling". Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- "Albuquerque Sister Cities". cabq.gov. City of Albuquerque. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- "Orașe înfrățite". primariabistrita.ro (in Romanian). Bistrița. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- "Jumelages et coopérations". grenoble.fr (in French). Grenoble. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- "Partnerstädte". heidelberg.de (in German). Heidelberg. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- "Indice Digesto Municipal: Relaciones Internacionales". parana.gob.ar (in Spanish). Paraná. 2 September 2010. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- "Rochester Sister Cities". rochestersistercities.org. International Sister Cities of Rochester. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- "Партнерски градови (Main Page)". valjevo.rs (in Serbian). Valjevo. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- Paraszczuk, Joanna (3 December 2010). "Rehovot keeps an eye on the past as it looks to the future". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- "Glickstein, Shlomo". Jews in Sports. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- Lehmann, Sara (1 July 2009). "Likud's Rising Star – Single, Female And Religious". The Jewish Press. Archived from the original on 5 July 2009. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- Associated Press (30 May 2009). "Israel's fourth president Ephraim Katzir dies at 93: World renowned biophysicist and Israel Prize laureate dies at his Rehovot home". Haaretz. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- "Knesset Members: Shmuel Rechtman". The Knesset. 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- "Knesset Members: David Tal". The Knesset. 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- "Zionist Leaders: Chaim Weizmann, 1874–1952". Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 11 October 1999. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- "Israel Prize Official Site (in Hebrew) – Recipient's C.V." Retrieved 23 March 2011.

External links

- City council website (in Hebrew)

- Rehovot at the Jewish Virtual Library

- English language guide to Rehovot

- Rehovot at Curlie