Reddy

Reddy (also transliterated as Raddi, Reddi, Reddiar, Reddappa, Reddy) is a caste that originated in India, predominantly settled in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. They are classified as a forward caste.

| Reddy | |

|---|---|

| Classification | Forward caste |

| Religions | Hinduism |

| Languages | |

| Country | India |

| Populated states | Major: Andhra Pradesh Telangana Minor: Karnataka Kerala Odisha Tamil Nadu |

| Region | South India |

| Kingdom (original) | Reddy Kingdom |

The origin of the Reddy has been linked to the Rashtrakutas, although opinions vary. They were feudal overlords and peasant proprietors.[1][2] Historically they have been the land-owning aristocracy of the villages.[3][4][5] Traditionally, they were a diverse community of merchants and cultivators.[1][6][7] Their prowess as rulers and warriors is well documented in Telugu history.[8] The Reddy dynasty (1325–1448 CE) ruled coastal and central Andhra for over a hundred years.

Origin theories

According to Alain Daniélou and Kenneth Hurry, the Rashtrakuta and Reddy dynasties may both have been descended from the earlier dynasty of the Rashtrikas.[9] This common origin is by no means certain: there is evidence suggesting that the Rashtrakuta line came from the Yadavas in northern India and also that they may simply have held a common title. Either of these alternate theories might undermine the claim to a connection between them and the Reddys.[10]

Varna status

The varna designation of Reddys is a contested and complex topic. Even after the introduction of the varna concept to south India, caste boundaries in south India were not as marked as in north India, where the four-tier varna system placed the priestly Brahmins on top followed by the Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Shudras. In south India, on the other hand, there existed only three distinguishable classes, the Brahmins, the non-Brahmins and the Dalits. The two intermediate dvija varnas—the Kshatriyas and Vaishyas—did not exist.[11][12][13][14]

The dominant castes of south India, such as Reddys and Nairs, held a status in society analogous to the Kshatriyas and Vaishyas of the north with the difference that religion did not sanctify them,[4][15][16] i.e. they were not accorded the status of Kshatriyas and Vaishyas by the Brahmins in the Brahmanical varna system. Historically, land-owning castes like the Reddys have belonged to the regal ruling classes and are analogous to the Kshatriyas of the Brahmanical society.[17]

The Brahmins, on top of the hierarchical social order, viewed the ruling castes of the south like the Reddys, Nairs and Vellalars as sat-Shudras meaning shudras of "true being". Sat-shudras are also known as clean shudras, upper shudras, pure or high-caste shudras.[18][19] This classification and the four-tier varna concept was never accepted by the ruling castes.[20][21]

History

Medieval history

Kakatiya period

During the Kakatiya period, Reddi, together with its variant Raddi, was used as a status title (gaurava-vachakamu). The title broadly represented the category of village headmen irrespective of their hereditary background.[22]

The Kakatiya prince Prola I (c. 1052 to 1076) was referred to as "Prola Reddi" in an inscription.[23][24] After the Kakatiyas became independent rulers in their own right, various subordinate chiefs under their rule are known to have used the title Reddi.[25] Reddy chiefs were appointed as generals and soldiers under the Kakatiyas. Some Reddys were among the feudatories of Kakatiya ruler Pratapa Rudra. During this time, some of the Reddys carved out feudal principalities for themselves. Prominent among them were the Munagala Reddy chiefs. Two inscriptions found in the Zamindari of Munagala at Tadavayi, two miles west of Munagala—one dated 1300 CE, and the other dated 1306 CE show that the Munagala Reddy chiefs were feudatories to the Kakatiya dynasty. The inscriptions proclaim Annaya Reddy of Munagala as a chieftain of Kakatiya ruler Pratapa Rudra.

The Reddy feudatories fought against attacks from the Delhi sultanate and defended the region from coming under the Turkic rule.[26] Eventually, the Sultanate invaded Warangal and captured Pratapa Rudra in 1323.

Reddi kingdom

After the death of Pratapa Rudra in 1323 CE and the subsequent fall of the Kakatiya empire, some Reddi chiefs became independent rulers. Prolaya Vema Reddi proclaimed independence, establishing a "Reddi dynasty" based in Addanki.[27][28][29] He had been part of a coalition of Telugu rulers who overthrew the "foreign" ruler (Turkic rulers of the Delhi Sultanate).[29]

The dynasty (1325–1448 CE) ruled coastal and central Andhra for over a hundred years.[30][31]

Vijayanagara period

The post-Kakatiya period saw the emergence of Vijayanagara Empire as well as the Reddy dynasty.[28] Initially, the two kingdoms were locked up in a territorial struggle for supremacy in the coastal region of Andhra. Later, they united and became allies against their common archrivals—the Bahmani sultans and the Recherla Velamas of Rachakonda who had formed an alliance. This political alliance between Vijayanagara and the Reddy kingdom was cemented further by a matrimonial alliance. Harihara II of Vijayanagara gave his daughter in marriage to Kataya Vema Reddy's son Kataya. The Reddy rulers exercised a policy of annexation and invasion of Kalinga (modern day Odisha). However, the suzerainty of Kalinga rulers was to be recognised. In 1443 CE, determined to put an end to the aggressions of the Reddy kingdom, the Gajapati ruler Kapilendra of Kalinga formed an alliance with the Velamas and launched an attack on the Reddy kingdom. Veerabhadra Reddy allied himself with Vijayanagara ruler Devaraya II and defeated Kapilendra. After the death of Devaraya II in 1446 CE, he was succeeded by his son, Mallikarjuna Raya. Overwhelmed by difficulties at home, Mallikarjuna Raya recalled the Vijayanagara forces from Rajahmundry. Veerabhadra Reddy died in 1448 CE. Seizing this opportunity, Kapilendra sent an army under the leadership of his son Hamvira into the Reddy kingdom, took Rajahmundry and gained control of the Reddy kingdom. The Gajapatis eventually lost control after the death of Kapilendra, and the territories of the former Reddy kingdom came under the control of the Vijayanagara Empire.[32]

Later, Reddys became the military chieftains of the Vijayanagara rulers. They along with their private armies accompanied and supported the Vijayanagara army in the conquest of new territories. These chieftains were known by the title of Poligars.[33] The Reddy poligars were appointed to render military services in times of war, collect revenue from the populace and pay to the royal treasury. The chieftains exercised considerable autonomy in their respective provinces. The ancestors of the legendary Uyyalawada Narasimha Reddy – who led an armed rebellion against the British East India company, were poligars.[34] Reddys were historically dominant in the Rayalaseema region.[35]

Once independent, the erstwhile chiefs of the Vijayanagara empire indulged in several internal squabbles for supremacy in their areas. This constant warring between powerful feudal warlords for fiefdoms and power manifests itself even in modern-day Rayalaseema in the form of a brutally violent phenomenon termed as “factionalism”, "factional violence" or simply "faction".[36]

Modern history

Golkonda period

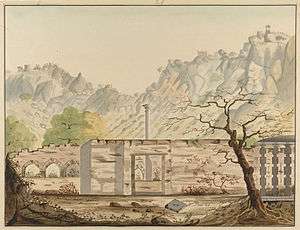

During this period, Reddys ruled several "samsthanams" (tributary estates)[37] in the Telangana area. They ruled as vassals of Golkonda sultans. Prominent among them were Ramakrishna Reddy, Pedda Venkata Reddy and Immadi Venkata Reddy. In the 16th century, the Pangal fort situated in Mahbubnagar district of Andhra Pradesh was ruled by Veera Krishna Reddy. Immadi Venkata Reddy was recognised by the Golkonda sultan Abdullah Qutb Shah as a regular provider of military forces to the Golkonda armies.[38] The Gadwal samsthanam situated in Mahbubnagar includes a fort built in 1710 CE by Raja Somtadari.[37] Reddys continued to be chieftains, village policemen and tax collectors in the Telangana region, throughout the Golkonda rule.

British period

One of most prominent figures from the community during the British period is Uyyalawada Narasimha Reddy. He challenged the British and led an armed rebellion against the British East India company in 1846. He was finally captured and hanged in 1847. His uprising was one of the earlier rebellions against the British rule in India, as it was 10 years before the famous Indian Rebellion of 1857.[39]

Reddys were the landed gentry known as the deshmukhs and part of the Nizam of Hyderabad's administration.[40] The Reddy landlords styled themselves as Desais, Doras and Patel. Several Reddys were noblemen in the court of Nizam Nawabs and held many high positions in the Nizam's administrative set up. Raja Bahadur Venkatarama Reddy was made Kotwal of Hyderabad in 1920 CE during the reign of the seventh Nizam Osman Ali Khan, Asaf Jah VII. Raja Bahadur Venkatarama Reddy was the first Hindu to be made kotwal of Hyderabad as in the late 19th and early 20th century, during the Islamic rule of the Nizams, the powerful position of Kotwal was held only by Muslims. His tenure lasted almost 14 years and he commanded great respect among the public for his outstanding police administration.[41][42]

Several Reddys were at the forefront of the anti-Nizam movement. In 1941, communist leaders Raavi Narayana Reddy and Baddam Yella Reddy transformed the Andhra Mahasabha into an anti-Nizam united mass militant organisation and led an armed struggle against the Nizam's regime.[43]

Modern politics

Kammas and Reddys are politically dominant castes prior to the formation of Andhra Pradesh in 1956 and after.[47] Reddys are classified as a Forward Caste in modern India's positive discrimination system.[48] They are a politically dominant community in Andhra Pradesh, their rise having dated from the formation of the state in 1956.[49]

See also

- List of Reddys

Notes and references

- Frykenberg, Robert Eric (1965). Guntur district, 1788–1848: A History of Local Influence and Central Authority in South India. Clarendon Press. p. 275.

- Y. Subhashini Subrahmanyam (1975). Social change in village India: an Andhra case study. Prithvi Raj Publishers. p. 75. Retrieved 25 July 2011.

- David E. Ludden (1999). An Agrarian History of South Asia. Cambridge University Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-521-36424-9.

- Lohia, Rammanohar (1964). The Caste System. Navahind. pp. 93–94, 103, 126.

- Karen Isaksen Leonard (2007). Locating home: India's Hyderabadis abroad. Stanford University Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-8047-5442-2.

- Stein, Burton (1989). Vijayanagara. Cambridge University Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-521-26693-2.

- Robert, Bruce L. (1982). Agrarian Organization and Resource Distribution in South India: Bellary District 1800–1979. University of Wisconsin–Madison. p. 88.

- Subrahmanyam, Sanjay (2001). Penumbral Visions: Making Polities in Early Modern South India. University of Michigan Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-472-11216-6.

- Daniélou, Alain; Hurry, Kenneth (2003). A Brief History of India. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-89281-923-2.

- Chopra, Pran Nath (2003). A Comprehensive History of Ancient India. 3. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. p. 202. ISBN 978-81-207-2503-4.

- Jalal, Ayesha (1995). Democracy and Authoritarianism in South Asia: A Comparative and Historical Perspective. Cambridge University Press. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-521-47862-5.

- Bernard, Jean Alphonse (2001). From Raj to the Republic: A Political History of India, 1935–2000. Har Anand Publications. p. 37.

- Joseph, M. P. (2004). Legitimately Divided: Towards a Counter Narrative of the Ethnographic History of Kerala Christianity. Christava Sahitya Samithi. p. 62. ISBN 978-81-7821-040-7.

- Raychaudhuri, Tapan; Habib, Irfan; Kumar, Dharma (1982). The Cambridge Economic History of India: c.1200–c.1750. Cambridge University Press Archive. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-521-22692-9.

- M. P. Joseph (2004). Legitimately divided: towards a counter narrative of the ethnographic history of Kerala Christianity. Christava Sahitya Samithi. p. 62. ISBN 978-81-7821-040-7.

- Shah, Ghanshyam (2004). Caste and Democratic Politics in India. Anthem Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-84331-086-0.

- Richman, Paula (2001). Questioning Rāmāyaṇas: a South Asian tradition. University of California Press. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-520-22074-4.

- D. Dennis Hudson (2000). Protestant origins in India: Tamil Evangelical Christians, 1706–1835. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-8028-4721-8.

- Ayres, Alyssa; Oldenburg, Philip (2002). India Briefing: Quickening the Pace of Change. M.E. Sharpe. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-7656-0813-0.

- G. Krishnan-Kutty (1999). The political economy of underdevelopment in India. Northern Book Centre. p. 172. ISBN 978-81-7211-107-6.

- Krishnan-Kutty, G. (1986). Peasantry in India. Abhinav Publications. p. 10. ISBN 978-81-7017-215-4.

- Talbot, Pre-colonial India in Practice 2001, pp. 55, 59.

- Diskalkar, D. B. (1993), Sanskrit and Prakrit Poets Known from Inscriptions, Anandashram Samstha, p. 122 Quote: "Balasarasvati, author of an inscription dated S. 1135 [c. 1057 CE] had lived at the court of Prola Reddi, ruler of the same Kakatiya [dynasty]."

- Archaeological Survey of India (2000). Indian Archaeology: A Review. Archaeological Survey of India. p. 123.

- Talbot, Pre-colonial India in Practice 2001, p. 98.

- Dikshit, Giri S.; Srikantaya, Saklespur; Pratiṣṭhāna, Bi. Eṃ. Śrī. Smāraka (1988). Early Vijayanagara: Studies in its History & Culture: Proceedings of S. Srikantaya Centenary Seminar. B.M.S. Memorial Foundation. p. 131.

- K. V. Narayana Rao (1973). The emergence of Andhra Pradesh. Popular Prakashan. p. 4. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- P. Sriramamurti (1972). Contribution of Andhra to Sanskrit literature. Andhra University. p. 60. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- Amaresh Datta; Mohan Lal (1992). Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: Sasay-Zorgot. Sahitya Akademi. p. 4637.

- Pran Nath Chopra (1982). Religions and communities of India. Vision Books. p. 136. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- Mallampalli Somasekhara Sarma; Mallampalli Sōmaśēkharaśarma (1948). History of the Reddi kingdoms (circa 1325 A.D. to circa 1448 A.D.). Andhra University. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2004). A history of India. Routledge. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-415-32919-4.

- A. Ranga Reddy (2003). The State of Rayalaseema. Mittal Publications. pp. 215, 333. ISBN 978-81-7099-814-3.

- Andhra Pradesh (India). District Gazetteers Dept (1992). Andhra Pradesh District Gazetteers: Kurnool. State editor, District Gazetteers. p. 55.

- Subrata Kumar Mitra (2004). Political parties in South Asia. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-275-96832-8.

- Balagopal, K. (23 July 1994). "Seshan in Kurnool". Economic and Political Weekly. 29 (30): 1905. JSTOR 4401511.

- Gadwal Samsthanam | Imperial Gazetteer of India, v.12, p.121.

- Benjamin B. Cohen (2002). Hindu rulers in a Muslim state L: Hyderabad, 1850–1949. University of Wisconsin–Madison. p. 78. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- D. P. Ramachandran (October 2008). Empire's First Soldiers. Lancer Publishers. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-9796174-7-8.

- Vasudha Chhotray (2011). The Anti-Politics Machine in India: State, Decentralization and Participatory Watershed Development. Anthem Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-85728-767-0.

- Basant K. Bawa (1992). The last Nizam: the life and times of Mir Osman Ali Khan. Viking. pp. 120–121. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- Raja Bahadur Venkatarama Reddy | Hyderabad Police online portal Archived 6 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Puccalapalli Sundarayya (2006). Telangana People's Struggle and Its Lessons. Foundation Books. p. 12. ISBN 978-81-7596-316-0.

- Andhra Pradesh (India); Bh Sivasankaranarayana (1976). Andhra Pradesh district gazetteers. Printed by the Director of Print. and Stationery at the Govt. Secretariat Press. p. 39,40.

- Kandavalli Balendu Sekaram (1973). The Andhras through the ages. Sri Saraswati Book Depot. p. 34.

- Gordon Mackenzie (1990). A manual of the Kistna district in the presidency of Madras. Asian Educational Services. pp. 9, 10, 224-. ISBN 978-81-206-0544-2.

- PrincetonPIIRS (13 November 2013), Dominant Caste and Territory in South India, retrieved 11 August 2016

- "Castes - Andhra (AP) Elections: News & Results". Archived from the original on 4 January 2012.

- Srinivasulu, K. (September 2002). "Caste, Class and Social Articulation in Andhra Pradesh: Mapping Differential Regional Trajectories" (PDF). London: Overseas Development Institute. p. 3. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

Bibliography

- Talbot, Cynthia (2001), Pre-colonial India in Practice: Society, Region, and Identity in Medieval Andhra, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19803-123-9

Further reading

- Sastri, K. A. Nilakanta (1958). A History of South India from Prehistoric Times to the Fall of Vijayanagara. Oxford University Press.