Harmony Society

The Harmony Society was a Christian theosophy and pietist society founded in Iptingen, Germany, in 1785. Due to religious persecution by the Lutheran Church and the government in Württemberg, the group moved to the United States,[1] where representatives initially purchased land in Butler County, Pennsylvania. On February 15, 1805, the group of approximately 400 followers formally organized the Harmony Society, placing all their goods in common.

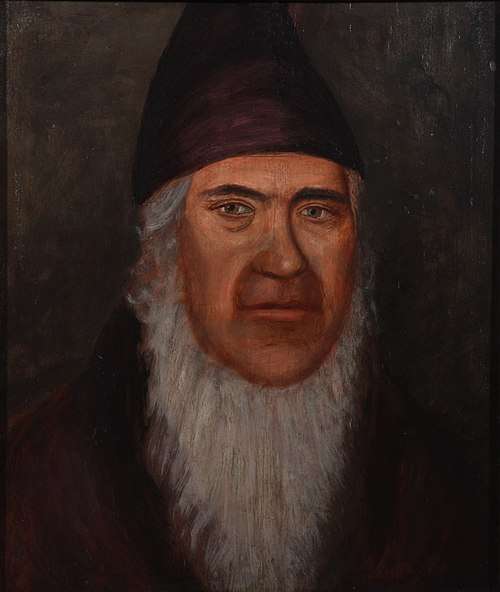

Under its founder and spiritual leader, Johann Georg Rapp (1757–1847); Frederick (Reichert) Rapp (1775–1834), his adopted son who managed its business affairs; and their associates, the Society existed for one hundred years, roughly from 1805 until 1905. Members were known as Harmonists, Harmonites, or Rappites. The Society is best known for its worldly successes, most notably the establishment of three model communities, the first at Harmony, Pennsylvania; the second, also called Harmony, in the Indiana Territory, now New Harmony, Indiana; and the third and final town at Economy, now Ambridge, Pennsylvania.

Origins in Germany

Johann Georg Rapp (1757–1847), also known as George Rapp, was the founder of the religious sect called Harmonists, Harmonites, Rappites, or the Harmony Society. Born in Iptingen, Duchy of Württemberg, Germany, Rapp was a "bright but stubborn boy" who was also deeply religious. His "strong personality" and religious convictions began to concern local church authorities when he refused to attend church services or take communion.[2] Rapp and his group of believers began meeting in Iptengen and eventually emigrated to the United States, where they established three communities: Harmony, Butler County, Pennsylvania; Harmony (later named New Harmony), Posey County, Indiana; and Economy, Beaver County, Pennsylvania.

Rapp became inspired by the philosophies of Jakob Böhme, Philipp Jakob Spener, Johann Heinrich Jung, and Emanuel Swedenborg, among others, and later wrote Thoughts on the Destiny of Man, published in German in 1824 and in English a year later, in which he outlined his ideas and philosophy.[3] Rapp lived out his remaining days in Economy, where he died on August 7, 1847, at the age of 89.[4]

By the mid-1780s, Rapp had begun preaching to the Separatists, his followers in Iptengen, who met privately and refused to attend church services or take communion.[5] As their numbers increased, Rapp's group officially split with the Lutheran Church in 1785 and was banned from meeting. Despite warnings from local authorities, the group continued to meet privately and attract even more followers.[6]

By 1798 Rapp and his group of followers had already begun to distance themselves from mainstream society and intended to establish a new religious congregation of fellow believers. In the Lomersheimer declaration, written in 1798, these religious Separatists presented their statement of faith, based on Christian principles, to the Wurttemberg legislature.[7] Rapp's followers declared their desire to form a separate congregation who would meet in members' homes, free from Lutheran Church doctrines. The group supported the belief that baptism was not necessary until children could decide for themselves whether they wanted to become a Christian. They also believed that confirmation for youth was not necessary and communion and confession would only be held a few times a year. Although the Separatists supported civil government, the group refused to make a physical oath in its support, "for according to the Gospel not oath is allowed him who gives evidence of a righteous life as an upright man."[8] They also refused to serve in the military or attend Lutheran schools, choosing instead to teach their children at home.[9] This declaration of faith, along with some later additions, guided the Harmony Society's religious beliefs even after they had emigrated from Germany to the United States.[10]

In the 1790s, Rapp's followers continued to increase, reaching as many as 10,000 to 12, 000 members.[11] The increasing numbers, which included followers outside of Rapp's village, continued to concern the government, who feared they might become rebellious and dangerous to the state.[12] Although no severe actions were initially taken to repress the Separatists, the group began to consider emigration to France or the United States. In 1803, when the government began to persecute Rapp's followers, he decided to move the entire group to the United States. Rapp and a small group of men left Iptingen in 1803 and traveled to America to find a new home.[13] On May 1, 1804, the first group of emigrants departed for the United States. The initial move scattered the followers and reduced Rapp's original group of 12,000 to just a few followers. Johan Frederich Reichert, who later agreed to become Rapp's adopted son and took the name of Frederick Reichert Rapp, reported in a letter dated February 25, 1804, that there were "at least 100 families or 500 persons actually ready to go" even if they had to sacrifice their property.[14]

Settlements in the United States

In 1804, while Rapp and his associates remained in the United States looking for a place to settle, his followers sailed to America aboard several vessels and made their way to western Pennsylvania, where they waited until land had been selected for their new settlement.[15] Rapp was able to secure a large tract of land in Pennsylvania and started his first commune, known as Harmonie or Harmony, in Butler County, Pennsylvania,[16] where the Society existed from 1804 to 1815.[17] It soon grew to a population of about 800, and was highly profitable. Ten years later, the town was sold and the Harmonists moved westward to the Indiana Territory, where they established the town of Harmony, now called New Harmony, Indiana, and remained there from 1815 to 1825.[17] The Indiana settlement was sold to Robert Owen and was renamed New Harmony. Ten years after the move to Indiana the commune moved again, this time returning to western Pennsylvania, and named their third and final town Economy ('Ökonomie' in German).[18] The Harmonists lived in Economy until the Society was dissolved in 1905.[17]

Articles of association

On February 15, 1805, the settlers at Harmony, Pennsylvania, signed articles of association to formally establish the Harmony Society in the United States. In this document, Society members agreed to hold all property in a common fund, including working capital of $23,000 to purchase land, livestock, tools, and other goods needed to establish their town.[19] The agreement gave the Society legal status in the United States and protected it from dissolution. Members contributed all of their possessions, pledged cooperation in promoting the interests of the group, and agreed to accept no pay for their services. In return, the members would receive care as long as they lived with the group. Under this agreement, if a member left the Society, their funds would be returned without interest or, if they had not contributed to the Society's treasury, they would receive a small monetary gift.[20]

The Society was a religious congregation who submitted to spiritual and material leadership under Rapp and his associates and worked together for the common good of all its members.[21] Believing that the Second Coming of Christ would occur during their lifetimes, the Harmonists contented to live simply under a strict religious doctrine, gave up tobacco, and advocated celibacy.[18]

First settlement: Harmony, Pennsylvania

In December 1804 Rapp and a party of two others initially contracted to purchase 4,500 acres (18 km2) of land for $11,250 in Butler County, Pennsylvania,[22] and later acquired additional land to increase their holdings to approximately 9,000 acres (36 km2) by the time they advertised their property for sale in 1814.[23] Here they built the town of Harmony, a small community that had, in 1805, nearly 50 log houses, a large barn, a gristmill, and more than 150 acres of cleared land to grow crops.[24]

Because the climate was not well suited for growing grapes and nearby property was not available to expand their landholdings, the Harmonists submitted a petition to the U.S. government for assistance in purchasing land elsewhere. In January 1806 Rapp traveled to Washington, D.C. to hear discussions in Congress regarding the Harmonists' petition for a grant that would allow them to purchase approximately 30,000 acres (120 km2) acre of land in the Indiana Territory. While the Senate passed the petition on January 29, it was defeated in the House of Representatives on February 18. The Harmonists had to find other financial means to support their plans for future expansion.[25] By 1810 the town's population reached approximately 700, with about 130 houses. The Society landholdings also increased to 7,000 acres (28 km2).[26] In the years that followed, the Society survived disagreements among its members, while shortages of cash and lack of credit threatened its finances. Still, the young community had a good reputation for its industry and agricultural production.[27]

At Harmony, George Rapp, also known as Father Rapp, was recognized as the spiritual head of the Society, the one that they went to for discussions, confessions, and other matters.[28] Rapp's adopted son, Frederick, managed the Society's business and commercial affairs.[29]

Rapp let newcomers into the Society and, after a trial period, usually about a year, they were accepted as permanent members.[20] While new members continued to arrive, including immigrants from Germany, others found the Harmonists' religious life too difficult and left the group.[30] In addition, during a period of religious zeal in 1807 and 1808, most, but not all, of the Harmonists adopted the practice of celibacy and there were also few marriages among the members. Rapp's son, Johannes, was married in 1807; and it was the last marriage on record until 1817.[31] Although Rapp did not entirely bar sex initially, it gradually became a custom and there were few births in later years.[32]

In 1811 Harmony's population rose to around 800 persons involved in farming and various trades.[33] Although profit was not a primary goal, their finances improved and the enterprise was profitable, but not sufficient to carry out their planned expansions.[34] Within a few years of their arrival, the Harmonist community included an inn, a tannery, warehouses, a brewery, several mills, stables, and barns, a church/meetinghouse, a school, additional dwellings for members, a labyrinth, and workshops for different trades. In addition, more land was cleared for vineyards and crops. The Harmonists also produced yarn and cloth.[35]

Several factors led to the Harmonists' decision to leave Butler County. Because the area's climate was not suitable, they had difficulties growing grapes for wine.[36] In addition, as westward migration brought new settlers to the county, making it less isolated, the Harmonists began having troubles with neighbors who were not part of the Society.[37] By 1814 Butler County's growing population and rising land prices made it difficult for the Society to expand, causing the group's leaders to look for more land elsewhere.[38] Once land had been located that offered a better climate and room to expand, the group began plans to move.[39] In 1814 the Harmonites sold their first settlement to Abraham Ziegler, a Mennonite, for $100,000 and moved west to make a new life for themselves in the Indiana Territory.[40]

Second settlement: Harmony, Indiana

In 1814 the Harmony Society moved to the Indiana Territory, where it initially acquired approximately 3,500 acres (14 km2) of land along the Wabash River in Posey County and later acquired more.[41] Over the next ten years the Society built a thriving new community they called Harmonie or Harmony on the Wabash in the Indiana wilderness. (The town's name was changed to New Harmony after the Harmonists left in 1824.) The Harmonists entered into agriculture and manufacture on a larger scale than they had done in Pennsylvania. When the Harmonists advertised their Indiana property for sale in 1824, they had acquired 20,000 acres (81 km2) of land, 2,000 acres (8.1 km2) of which was under cultivation.[42]

During the summer and fall of 1814, many Harmonists fell sick from fever (malaria) and work on the new town nearly ceased.[43] During this time the Society lost about 120 people and others fell ill until conditions were improved and the swamps around the area were drained.[28] Despite these illnesses, construction of the new town continued. By 1819 the Harmonites had built 150 log homes, a church, a community storehouse, barns, stables, and a tavern, along with thriving shops and mills, and cleared land for farming.[44] As the new settlement in Indiana grew, it also began to attract new arrivals, including emigrants from Germany, who expected the Harmonists to pay for their passage to America.[45]

Visitors to the new town commented on its growing commercial and industrial work. In 1819 the town had a steam-operated wool carding and spinning factory, a brewery, distillery, vineyards, and a winery,[46] but not all visitors were impressed with the growing communist town on the frontier.[47] The Society also had visitors from another communal religious society, the Shakers. In 1816 meetings between the Shakers and Harmonists considered a possible union of the two societies, but religious differences between the two groups halted the union.[48] Members of the groups remained, however, in contact over the years. George Rapp's daughter and others lived for a time at the Shaker settlement in West Union, Indiana, where the Shakers helped a number of Harmonites learn the English language.[49]

The Harmonist community continued to thrive during the 1820s. The Society shipped its surplus agricultural produce and manufactured goods throughout the Ohio and Mississippi valleys or sold them through their stores at Harmony and Shawneetown and their agents in Pittsburgh, Saint Louis, Louisville, and elsewhere.[50] Under Frederick Rapp's financial management the Society prospered, but he soon wished for a location better suited to manufacturing and commercial purposes.[51] They had initially selected the land near the Wabash River for its isolation and opportunity for expansion, but the Harmonites were now a great distance from the eastern markets and trade in this location wasn't to their liking. They also had to deal with unfriendly neighbors.[28] As abolitionists, the Harmonites faced disagreeable elements from slavery supporters in Kentucky, only 15 miles (24 km) away, which caused them much annoyance. By 1824 the decision had been made to sell their property in Indiana and search for land to the east.[52]

On January 3, 1825, the Harmonists and Robert Owen, a Welsh-born industrialist and social reformer, came to a final agreement for the sale of the Society's land and buildings in Indiana for $150,000. Owen named the town New Harmony, and by May, the last of the Harmony Society's remaining members returned to Pennsylvania.[53]

Third settlement: Economy, Pennsylvania

In 1824 Frederick Rapp initially purchased 1,000 acres (4.0 km2) along the Ohio River, 18 miles (29 km) northwest of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, for $10,000, and later bought an additional 2,186 acres (8.85 km2) for $33,445, giving the Society more than 3,000 acres (12 km2) to develop into a new community.[54] The Harmonites named their third and last town Economy, after the spiritual notion of the Divine Economy, "a city in which God would dwell among men" and where perfection would be attained.[55]

At Economy the Harmonists intended to become more involved in manufacturing and their new town on the Ohio River provided better access to eastern markets and water access to the south and west than they had in Indiana.[51] By 1826 the Harmonists had woolen and cotton mills in operation as well as a steam-operated grain mill.[56] The Harmonist society also ran a wine press, a hotel, post office, saw mills, stores, and a variety of farms.[57] Here, under the business acumen and efficient management of Frederick Rapp, they enjoyed such prosperity that by 1829 they dominated trade and the markets of Pittsburgh and down the Ohio River. The Harmonists' competitors accused them of creating a monopoly and called on state government to dissolve the group.[18] Despite the attacks, the Harmonists developed Economy into a prosperous factory town, engaged in farming on a large scale, and maintained a brewery, distillery, and wine-making operation.[58] They also pioneered the manufacturing of silk in the United States.[59]

The community was not neglectful of matters pertaining to art and culture. Frederick Rapp purchased artifacts and installed a museum containing fine paintings and many curiosities and antiques, but it proved to be unprofitable and was sold at a loss.[60] In addition, the Harmonists maintained a deer park, a floral park, and a maze, or labyrinth. The Harmonists were fond of music and many of the members were accomplished musicians. They sang, had a band/orchestra, composed songs, and gave much attention to its cultivation.[61] By 1830 they had amassed a 360-volume library.[60]

In 1832 the Society suffered a serious division. Of 750 members, 250 became alienated through the influence of Bernhard Müller (self-styled Count de Leon), who, with 40 followers (also at variance with the authorities in the old country), had come to Economy to affiliate with the Society. Rapp and Leon could not agree; a separation and apportionment of the property were therefore agreed upon. This secession of one-third of the Society, which consisted mostly of the flower of young manhood and young womanhood who did not want to maintain the custom of celibacy, broke Frederick's heart. He died within two years. It resulted in a considerable fracturing of the community. Nevertheless, the Society remained prosperous in business investments for many more years to come.

After Frederick Rapp's death in 1834, George Rapp appointed Romelius Baker and Jacob Henrici as trustees to manage the Society's business affairs.[62] After George Rapp's death in 1847, the Society reorganized. While a board of elders was elected for the enforcement of the Society's rules and regulations, business management passed to its trustees: Baker and Henrici, 1847–68; Henrici and Jonathan Lenz, 1869–90; Henrici and Wolfel, 1890; Henrici and John S. Duss, 1890–1892; Duss and Seiber, 1892–1893; Duss and Reithmuller, 1893–1897;Duss, 1897–1903; and finally to Suzanna (Susie) C. Duss in 1903.[63][64] By 1905 membership had dwindled to just three members and the Society was dissolved.[65]

The settlements at Economy remained economically successful until the late 19th century, producing many goods in their cotton and woolen factories, sawmill, tannery, and from their vineyards and distillery.[66] They also produced high quality silk for garments. Rapp's granddaughter, Gertrude, began the silk production in Economy on a small scale from 1826 to 1828, and later expanded.[67] This was planned in New Harmony, but fulfilled when they arrived at Economy.[28] The Harmonists were industrious and utilized the latest technologies of the day in their factories. Because the group chose to adopt celibacy and their members grew older, more work gradually had to be hired out. As their membership declined, they stopped manufacturing operations, other than what they needed for themselves, and began to invest in other ventures such as the oil business, coal mining, timber, railroads, land development, and banking.[65] The group invested in the construction of the Pittsburgh and Lake Erie Railroad, established the Economy Savings Institution and the Economy Brick Works, and operated the Economy Oil Company,[68] as well as the Economy Planing Mill, Economy Lumber Company, and eventually donated some land in Beaver Falls for the construction of Geneva College. The Society exerted a major influence on the economic development of Western Pennsylvania.[69]

Oil production in the mid-1860s brought the high-water mark of the Society's prosperity.[70] By the close of Baker's administration in 1868, The Society's wealth was probably $2 million. By 1890, however, the Society was in debt and on the verge of bankruptcy with a depleted and aged membership. In addition, the Society faced litigation from previous members and would-be heirs. The Society's trustee, John S. Duss, settled the lawsuits, liquidated its business ventures, and paid the Society's indebtedness.[65] The great strain which he had undergone at this time undermined his health and he resigned his trusteeship in 1903.[71] With only a few members left, the remaining land and assets were sold under the leadership of Duss's wife, Susanna (Susie), and the Society was formally dissolved in 1905.[65] At the time of the Society's dissolution, its net worth was $1.2 million.[72]

In 1916 the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania acquired 6 acres (0.024 km2) and 17 buildings of Economy, which became the Old Economy Village historic site. The American Bridge Company had already acquired other parts of the Society's land in 1902 to build the town of Ambridge.[65]

Characteristics

Religious views

In 1791 George Rapp said, "I am a prophet, and I am called to be one" in front of the civil affairs official in Maulbronn, Germany, who promptly had him imprisoned for two days and threatened with exile if he did not cease preaching.[73][74] To the great consternation of church and state authorities, this mere peasant from Iptingen had become the outspoken leader of several thousand Separatists in the southern German duchy of Württemberg.[1][73][74] By 1802 the Separatists had grown in number to about 12,000 and the Württemberg government decided that they were a dangerous threat to social order.[1] Rapp was summoned to Maulbronn for an interrogation, and the government confiscated Separatist books.[1] When released in 1803, from a brief time in prison, Rapp told his followers to pool their assets and follow him on a journey for safety to the "land of Israel" in the United States, and soon over 800 people were living with him there.[1]

The Harmonites were Christian pietist Separatists who split from the Lutheran Church in the late 18th century. Under the leadership of George Rapp, the group left Württemberg, Germany, and came to the United States in 1803. Due to the troubles they had in Europe, the group sought to establish a more perfect society in the American wilderness. They were nonviolent pacifists who refused to serve in the military and tried to live by George Rapp's philosophy and literal interpretations of the New Testament. They first settled and built the town of Harmony, Pennsylvania, in 1804, and established the Harmony Society in 1805 as a religious commune. In 1807, celibacy was advocated as the preferred custom of the community in an attempt to purify themselves for the coming Millennium. Rapp believed that the events and wars going on in the world at the time were a confirmation of his views regarding the imminent Second Coming of Christ, and he also viewed Napoleon as the Antichrist.[75] In 1814, the Society sold their first town in Pennsylvania and moved to the Indiana Territory, where they built their second town. In 1824, they decided it was time to leave Indiana, sold their land and town in Indiana, and moved to their final settlement in Western Pennsylvania.

The Harmonites were Millennialists, in that they believed Jesus Christ was coming to earth in their lifetime to help usher in a thousand-year kingdom of peace on earth. This is perhaps why they believed that people should try to make themselves "pure" and "perfect", and share things with others while willingly living in communal "harmony" (Acts 4:32-35) and practicing celibacy. They believed that the old ways of life on earth were coming to an end, and that a new perfect kingdom on earth was about to be realized.

They also practiced forms of Esoteric Christianity, Mysticism (Christian mysticism), and Rapp often spoke of the virgin spirit or Goddess named Sophia in his writings.[76] Rapp was very influenced by the writings of Jakob Böhme,[76] Philipp Jakob Spener, and Emanuel Swedenborg, among others. Also, at Economy, there are glass bottles and literature that seem to indicate that the group was interested in (and practiced) alchemy.[76] Other books found in the Harmony Society's library in Economy, include those by the following authors: Christoph Schütz, Gottfried Arnold, Justinus Kerner, Thomas Bromley,[77] Jane Leade, Johann Scheible (Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses),[78] Paracelsus, and Georg von Welling,[79] among others.[76]

The Harmonites tended to view unmarried celibate life as morally superior to marriage, based on Rapp's belief that God had originally created Adam as a dual being, having male and female sexual organs.[80] According to this view, when the female portion of Adam separated to form Eve, disharmony followed, but one could attempt to regain harmony through celibacy.

George Rapp predicted that on September 15, 1829, the three and one half years of the Sun Woman would end and Christ would begin his reign on earth.[75] Dissension grew when Rapp's predictions did not come to pass. In March 1832, one third of the group left the Society and some began following Bernhard Müller, who claimed to be the Lion of Judah. Nevertheless, most of the group stayed and Rapp continued to lead them until he died on August 7, 1847. His last words to his followers were, "If I did not so fully believe, that the Lord has designated me to place our society before His presence in the land of Canaan, I would consider this my last".[81]

The Harmonites did not mark their graves with headstones or grave markers, because they thought it was unnecessary to do so; however, one exception is George Rapp's son Johannes' stone marker in Harmony, Pennsylvania, which was installed by non-Harmonites many years after the Harmonites left that town.[82] Today, Harmonist graveyards are fenced in grassy areas with signs posted nearby explaining this practice.

Architecture

The Harmony Society's architecture reflected their Swabian German traditions, as well as the styles that were being developed in America during the 19th century. In the early days of the Society, many of the homes were initially log cabins and later, Harmonist craftsmen built timber-frame homes. At Economy, their homes were mostly two-story brick houses "that showed the influence of their American neighbors."[83] In general, Harmonist buildings, in addition to being sturdy and functional, were centrally heated, economical to maintain, and resistant to fire, weather, and termites.[84]

Once established at Harmony, Pennsylvania, the Society planned to replace the log dwellings with brick structures, but the group moved to the Indiana Territory before the plan was completed.[85] In Indiana, log homes were soon replaced with one- or two-story houses of timber frame or brick construction in addition to four large rooming houses (dormitories) for its growing membership. The new town also included shops, schools, mills, a granary, a hotel, library, distilleries, breweries, a brick kiln, pottery ovens, barn, stables, storehouses, and two churches, one of which was brick.[86]

In 1822 William Herbert, a visitor to Harmony, Indiana, described the new brick church and the Harmonists' craftsmanship:

"These people exhibit considerable taste as well as boldness of design in some of their works. They are erecting a noble church, the roof of which is supported in the interior by a great number of stately columns, which have been turned from trees in their own forests. The kinds of wood made use of for this purpose are, I am informed, black walnut, cherry and sassafras. Nothing I think can exceed the grandeur of the joinery and the masonry and brickwork seem to be of the first order. The form of this church is that of a cross, the limbs being short and equal; and as the doors, which there are four, are placed at the end of the limbs, the interior of the building as seen from the entrance, has a most ample and spacious effect.... I could scarcely imagine myself to be in the woods of Indiana, on the borders of the Wabash, while pacing the long resounding aisles, and surveying the stately colonnades of this church."[28]

Frame structures were built on piers to keep the air circulating across the area's damp soil, while brick structures had a root cellar with a drainage tunnel. Inside, Harmonists built fireplaces to the left or right of center to allow for a long center beam, adding strength to support the structure and its heavy, shingled roof. "Dutch biscuits" (wood laths wrapped in straw and mud) provided insulation and soundproofing between the ceiling and floors. The exterior was insulated with bricks between the exterior's unpainted weatherboards and the interior's lath and plaster walls.[87] Structures had standard parts and pre-cut, pre-measured timbers, which were assembled on the ground, adjusted to fit on site, raised in place, and locked into place with pegs and mortise and tenon joints.[88] Two-story floor plans for homes included a large living room, kitchen, and entrance hall, with stairs to the second floor and attic. In Indiana, Harmonists did their baking in communal ovens, so stoves could be substituted for fireplaces.[89]

Living styles

At Harmony, Pennsylvania, four to six members were assigned to a home, where they lived as families, although not all those living in the household were related.[85] Even when the house contained those that were married, they would live together as brother and sister, since there was a suggestion and custom of practicing celibacy. In Indiana, Harmonists continued to live in homes, but they also built dormitories to house single men and women.[28]

Society members woke between 5 a.m. and 6 a.m. They ate breakfast between 6 a.m. and 7 a.m., lunch at 9 a.m., dinner at noon, afternoon lunch at 3 p.m., and supper between 6 p.m. and 7 p.m.[90] They did their chores and work during the day. At the end of the day, members met for meetings and had a curfew of 9 p.m. On Sundays, the members respected the "Holy day" and did no unnecessary work, but attended church services, singing groups, and other social activities.[28]

Clothing

Their style of dress reflected their Swabian German roots and traditions and was adapted to their life in America.[91] Although the Harmonites typically wore plain clothing, made with their own materials by their own tailors, they would wear their fine garments on Sundays and on other special occasions. At Economy, on special occasions and Sundays, women wore silk dresses using fabric of their own manufacture.[91] Clothing varied in color, but often carried the same design. On a typical day, women wore ankle-length dresses, while men wore pants with vests or coats and a hat.[28]

Technology

The Harmonites were a prosperous agricultural and industrial people. They had many machines that helped them be successful in their trades. They even had steam-powered engines that ran the machines at some of their factories in Economy. They kept their machines up to date, and had many factories and mills, for example Beaver Falls Cutlery Company which they purchased in 1867.[92]

Work

Each member of the Society had a job in a certain craft or trade. Most of the work done by men consisted of manual labor, while the women dealt more with textiles or agriculture.

As Economy became more technologically developed, Harmonites began to hire others from outside the Society, especially when their numbers decreased because of the custom of celibacy and as they eventually let fewer new members join. Although the Harmonites did seek work-oriented help from the outside, they were known as a community that supported themselves, kept their ways of living in their community, mainly exported goods, and tried to import as little as possible.

Rise and fall of Harmony Society

George Rapp had an eloquent style, which matched his commanding presence, and he was the personality that led the group through all the different settlements. After Rapp's death in 1847, a number of members left the group because of disappointment and disillusionment over the fact that his prophecies regarding the return of Jesus Christ in his lifetime were not fulfilled. However, many stayed in the group, and the Harmony Society went on to become an even more profitable business community that had many worldly financial successes under the leadership of Romelius L. Baker and Jacob Henrici.

Over time the group became more protective of itself, did not allow many new members, moved further from its religious foundation to a more business-oriented and pragmatic approach, and the custom of celibacy eventually drained it of its membership. The land and financial assets of the Harmony Society were sold off by the few remaining members under the leadership of John Duss and his wife, Susanna, by the year 1906.

Today, many of the Society's remaining buildings are preserved; all three of their settlements in the United States have been declared National Historic Landmark Districts by the National Park Service.

See also

- Ambridge, Pennsylvania

- Economy, Pennsylvania

- Freedom, Pennsylvania

- Geneva College

- Harmonie State Park

- Harmony, Pennsylvania

- Harmony Historic District

- Harmony Township, Beaver County, Pennsylvania

- New Harmony Historic District

- New Harmony, Indiana

- New International Encyclopedia

- Old Economy Village

- Pittsburgh and Lake Erie Railroad

- Zoar, Ohio

References

- Robert Paul Sutton, Communal Utopias and the American Experience: Religious Communities (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2004) p. 38.

- Karl J. R. Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, 1785–1847 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1965), p. 17–18.

- John Archibald Bole, The Harmony Society: A Chapter in German American Culture History (Philadelphia: Americana Germanica Press, 1904) p. 45, 65.

- Karl J. R. Arndt, George Rapp's Successors and Material Heirs, 1847–1916 (Rutherford, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1971), p. 17.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 20.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 30.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 35.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 39.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 38–39.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 40.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 46.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 49.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 49–50.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 54.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 65–69.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 72.

- Karl J. R. Arndt, The Harmony Society from its beginnings in Germany in 1785 to its Liquidation in the United States in 1905 (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1953), p. 189.

- David Schwab, comp. (2010-05-20). "The Harmony Society". U.S. Army Corps of Engineers–Pittsburg District. Archived from the original on 2012-02-07. Retrieved 2012-06-04.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 71.

- Bole, p. 33–34.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 75.

- William E. Wilson, The Angel and the Serpent: The Story of New Harmony (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1964), p. 13.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 135, 137.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 76.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 84, 86–90.

- Christiana F. Knoedler, The Harmony Society: A 19th-Century American Utopia (New York: Vantage Press, 1954), p. 10–11.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 92.

- Historic New Harmony (2008). "The Harmonie Society" (PDF). University of Southern Indiana. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-30. Retrieved 2012-06-13.

- Wilson, p. 15–16.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 100.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 97–99.

- Wilson, p. 24–25.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 121.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 123–127.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 105–107, 112.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 84.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 130–131.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 133.

- Ray E. Boomhower, "New Harmony: Home to Indiana's Communal Societies," Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History, 14(4):36.

- Wilson, p. 37–38.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 145.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 295.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 147.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 206–207.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 182–198.

- Karl J. R. Arndt, A Documentary History of the Indiana Decade of the Harmony Society 1814–1824 (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society, 1975), 1:744–745.

- Arndt, A Documentary History of the Indiana Decade of the Harmony Society, 1:784.

- Arndt, A Documentary History of the Indiana Decade of the Harmony Society, 1:225–229.

- Arndt, A Documentary History of the Indiana Decade of the Harmony Society, 1:230.

- Bole, p. 79.

- Bole, p. 91.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 287.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 298.

- Knoedler, p. 19, 22.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 306.

- Knoedler, p. 23.

- John M. Tate, Jr. Collection of Notes, Pictures and Documents relating to the Harmony Society, 1806-1930, DAR.1946.02, Darlington Library, Special Collections Department, University of Pittsburgh

- Bole, p. 107.

- Arndt, The Harmony Society from its beginnings in Germany in 1785 to its Liquidation in the United States in 1905, p. 190.

- Bole, p. 148.

- Knoedler, p. 79–83.

- Daniel B. Reibel, A Guide to Old Economy (Old Economy, PA: Harmonie Associates, 1969), p. 8–9.

- Bole, p. 141–142, 229.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Successors and Material Heirs, p. 99.

- Reibel, p. 9.

- Bole, p. 97, 107, 113.

- Knoedler, p. 58–60.

- Bole, p. 133, 135.

- Knoedler, p. 148.

- Bole, p. 133.

- J. S. Duss, The Harmonists: A Personal History (Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Book Service, 1943), p. 359–360.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Successors and Material Heirs, p. 328.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, 1785–1847, p. 30.

- Donald E. Pitzer, America's Communal Utopias (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1997) p. 57.

- Frederic J. Baumgartner, Longing for the End: A History of Millennialism in Western Civilization (1999) p. 166.

- Arthur Versluis, "Western Esotericism and The Harmony Society", Esoterica I (1999) p. 20–47. Michigan State University

- PasstheWORD (2005-10-13). "Thomas Bromley On-Line Manuscripts". PasstheWORD. Retrieved 2012-06-15.

- Joseph H. Peterson (2005). "The Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses". Esotericarchives.com. Retrieved 2012-06-15.

- Georg von Welling (1784, third ed., edited and translated by Arthur Versluis). "Opus Mago-Cabalisticum". Frankfurt and Leipzig: The Fleischer Bookstore. Retrieved 2012-06-15. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Arndt, George Rapp's Successors and Material Heirs, p. 147.

- Wilson, p. 11.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Successors and Material Heirs, p. 157.

- Don Blair, "Harmonist Construction. Principally as found in the two-story houses built in Harmonie, Indiana, 1814–1824," Indiana Historical Society Publications 23, no. (1964): 81.

- Blair, p. 82.

- Arndt, George Rapp's Harmony Society, p. 109.

- Blair, p. 49–50.

- Blair, p. 52–54, 76.

- Blair, p. 57.

- Blair, p. 66, 71, 73.

- Bole, p. 145.

- Bole, p. 146.

- Anon (1993). "Gone but not forgotten: the Beaver Falls Cutlery Company". Industrious Beaver Falls. Darlington, Pennsylvania: Beaver County Industrial Museum. This is based on Anon (1992). "The history and lore of Beaver Co.: the Chinese in Beaver Falls 1872". The Beaver Countian Vol III no.1. Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania. pp. 1–3.

Bibliography

- Arndt, Karl J. R. A Documentary History of the Indiana Decade of the Harmony Society 1814–1824. 2 vols. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society, 1975–78.

- Arndt, Karl J. R. Economy on the Ohio, 1826–1834: The Harmony Society During the Period of its Greatest Power and Influence and its Messianic Crisis; George Rapp's Third Harmony: A Documentary History. Worcester, Mass.: Harmony Society Press, 1984.

- Arndt, Karl J. R. George Rapp's Harmony Society, 1785–1847. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1965.

- Arndt, Karl J. R. George Rapp's Re-Established Harmony Society: Letters and Documents of the Baker-Henrici Trusteeship, 1848–1868. New York: P. Lang, 1993.

- Arndt, Karl J. R. George Rapp's Separatists, 1700–1803: The German Prelude to Rapp's American Harmony Society; A Documentary History. Worcester, Mass.: Harmonie Society Press, 1980.

- Arndt, Karl J. R. George Rapp's Successors and Material Heirs, 1847–1916. Rutherford, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1971.

- Arndt, Karl J. R. George Rapp's Years of Glory: Economy on the Ohio, 1834–1847. New York: P. Lang, 1987.

- Arndt, Karl J. R. Harmony on the Connoquenessing 1803–1815: George Rapp's First American Harmony. Worcester, Mass.: Harmonie Society Press, 1980.

- Arndt, Karl J. R. Harmony on the Wabash in Transition to Rapp's Divine Economy on the Ohio and Owen's New Moral World at New Harmony on the Wabash 1824–1826. Worcester, Mass.: Harmonie Society Press, 1984.

- Arndt, Karl J. R. The Harmony Society from its Beginnings in Germany in 1785 to its Liquidation in the United States in 1905. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1953.

- Arndt, Karl J. R. The Indiana Decade of George Rapp's Harmony Society: 1814–1824. Worcester, Mass.: American Antiquarian Society, 1971.

- Arndt, Karl J. R., Donald Pitzer and Leigh Ann Chamness (eds.) George Rapp's Disciples, Pioneers, and Heirs: A Register of the Harmonists in America. Evansville: University of Southern Indiana, 1992.

- Baumgartner, Frederic J. Longing for the End: A History of Millennialism in Western Civilization. New York: Saint Martin's Press, 1999.

- Berry, Brian J. L. America's Utopian Experiments: Communal Havens from Long-Wave Crises. Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College and University Press of New England, 1992.

- Bestor, Arthur. Backwoods Utopias. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1950.

- Blair, Don. Harmonist Construction. Principally as found in the two-story houses built in Harmonie, Indiana, 1814–1824. Indiana Historical Society Publications 23, no. 2. (1964): 45–82.

- Bole, John Archibald. The Harmony Society: A Chapter in German American Culture History. Philadelphia: Americana Germanica Press, 1904.

- Boomhower, Ray E. "New Harmony: Home to Indiana's Communal Societies." Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History 14, no. 4 (2002): 36–37.

- Bowden, Henry W. Dictionary of American Religious Biography. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1977.

- Brooks, Joshua Thwing. Jacob Henrici. Sewickley, PA: Gilbert Adams Hays, 1922.

- Byrd, Cecil K. The Harmony Society and Thoughts on the Destiny of Man. Bloomington, IN, 1956.

- Cross, Frank L. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1974.

- Dare, Philip N. American Communes to 1860: A Bibliography. New York: Garland, 1990.

- Douglas, Paul S. The Material Culture of the Harmony Society. Pennsylvania Folklife 24, no. 3 (Spring, 1975).

- Dructor, Robert M. Guide to the Microfilmed Harmony Society Records, 1786–1951 in the Pennsylvania State Archives. Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1983.

- Dructor, Robert M. The Harmonists: A Personal History. Pittsburgh: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1970.

- Dudley, Lavinia P., John H. Archer, Tucker Abbot, et al. The Encyclopedia Americana: The International Reference Work New York: Americana Corp., 1963.

- Durnbaugh, Donald F. Radical Pietism as the Foundation of German-American Communitarian Settlements." In Emigration and Settlement Patterns of German Communities in North America, p. 31–54. Eberhard Reichmann, LaVern J. Rippley and Joerg Nagler, eds. Indianapolis: Max Kade German-American Center, Indiana University–Purdue University, Indianapolis, 1995.

- Duss, J. S. George Rapp and His Associates. Indianapolis, IN: Hollenbeck Press, 1914.

- Duss, J. S. The Harmonists: A Personal History. Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Book Service, 1943.

- English, Eileen A. "A Brief Interlude of Peace for George Rapp's Harmony Society." Communal Societies 26.1 (2006): 37–45.

- Federal Writers' Project (Beaver County, PA). The Harmony Society in Pennsylvania. Philadelphia, PA: William Penn Association, 1937.

- Feurige Kohlen, der aufsteigenden Liebesflammen im Lustspiel der Weisheit; einer nachdenkenden Gesellschaft gewidmet. Harmony Society in Oekonomie, Pennsylvania, 1826.

- Fogarty, Robert S. All Things New: American Communes and Utopian Movements, 1860–1914. University of Chicago Press, 1990.

- Fogarty, Robert S. Dictionary of American Communal and Utopian History. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1980.

- Fritz, Eberhard. Johann Georg Rapp (1757–1847) und die Separatisten in Iptingen. Mit einer Edition der relevanten Iptinger Kirchenkonventsprotokolle. Blätter für Wuerttembergische Kirchengeschichte 95/1995. S. 129–203.

- Fritz, Eberhard. Radikaler Pietismus in Württemberg. Religioese Ideale im Konflikt mit gesellschaftlichen Realitaeten. Quellen und Forschungen zur wuerttembergischen Kirchengeschichte Band 18. Epfendorf 2003.

- Fritz, Eberhard. Separatistinnen und Separatisten in Wuerttemberg und in angrenzenden Territorien. Ein biografisches Verzeichnis. Arbeitsbücher des Vereins für Familien- und Wappenkunde. Stuttgart 2005. (Register of Separatists in Wuerttemberg, including most of Rapp's followers.)

- Gormly, Agnes M. Hays. Economy: A Unique Community. Sewickley, PA: Gilbert Adams Hays, 1910.

- Gormly, Agnes M. Hays. Old Economy: The Harmony Society. Sewickley, PA: Gilbert Adams Hays, 1904.

- Hays, George A. The Churches of the Harmony Society. Ambridge, PA: Old Economy, 1964.

- Hays, George A. Founders of the Harmony Society. Ambridge, PA: Old Economy, 1961.

- Henderson, Lois T. The Holy Experiment: A Novel About the Harmonist Society. [Fiction]. Hicksville, NY: Exposition Press, 1974.

- Hinds, Alfred. American Communities. rev. ed. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr and Co., 1902.

- Historic New Harmony. (2008). "The Harmonie Society". University of Southern Indiana. Retrieved 2012-6-15.

- Holloway, Mark. Heavens on Earth: Utopian Communities in America, 1680–1880. New York: Dover Publications, 1966.

- Karl Bernhard of Saxe Weimar Eisenach, Travels through North America, during the Years 1825 and 1826 2 vols. Philadelphia, 1828.

- Knoedler, Christiana F. The Harmony Society: A 19th-Century American Utopia. New York: Vantage Press, 1954.

- Kring, Hilda. The Harmonists: A Folk-Cultural Approach. Metuchen, NY: The Scarecrow Press and The American Theological Library Association, 1973.

- Krueger, Nancy. "The Woolen and Cotton Manufactory of the Harmony Society with Emphasis on the Indiana Years 1814–1825." M.A. thesis, State University of New York College at Oneonta, 1983.

- Larner Jr., John W. "Nails and Sundrie Medicines: Town Planning and Public Health in the Harmony Society, 1805–1840." The Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine 45, no. 2 (June 1962): 115–138.

- Lockridge Jr., Ross. The Labyrinth. Westport, Conn. Hyperion, 1975.

- Lockwood, George Browning. The New Harmony Communities. Marion, IN: Chronicle Company, 1902.

- Mason, Harrison Denning. Old Economy as I knew it: Impressions of the Harmonites, their village and its surroundings, as seen almost a half-century ago. Crafton, PA: Cramer Printing and Publishing Company, 1926.

- Matter, Evelyn P. The Great House [George Rapp House] Constructed 1826 and Frederick Rapp House Constructed about 1828 at Old Economy. Old Economy, PA: Harmonie Associates, 1970.

- Miller, Melvin R. "Education in the Harmony Society, 1805–1905." Ph.D. diss., University of Pittsburgh, 1972.

- Morris, James Matthew, and Andrea L. Kross. Historical Dictionary of Utopianism. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 2004.

- Nordhoff, Charles. Communistic Societies of the United States. New York, 1874.

- Oved, Yaacov. Two Hundred Years of American Communes. Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books, 1988.

- Passavant, William A., "A Visit to Economy in the Spring of 1840." Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine 4 (July 1921): 144–149.

- Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Bibliography of the Harmony Society: With Special Reference to Old Economy. Ambridge: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1968.

- Pitzer, Donald E. America's Communal Utopias. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

- Pitzer, Donald E., and Josephine M. Elliott. New Harmony's first Utopians, 1814–1824. Indiana Magazine of History 75, no. 3 (1979): 225–300.

- Rapp, George. Thoughts on the Destiny of Man Particularly with Reference to the Present Times. Harmony Society in Indiana, 1824.

- Rauscher, Julian. "Des Separatisten G. Rapp Leben und Treiben" Theologische Studien aus Württemberg 6 (1885): 253–313.

- Reibel, Daniel B. Bibliography of items related to the Harmony Society with special reference to Old Economy. Ambridge: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1969, rev. 1977.

- Reibel, Daniel B. A Guide to Old Economy. Old Economy, PA: Harmonie Associates, 1969.

- Reibel, Daniel B. Walking tour of the historic area of Ambridge, Pennsylvania: Being the former village of Economy, 1824–1902. Ambridge, PA: Harmonie Associates, 1978.

- Reibel, Daniel B., and Art Becker. Old Economy Village: Pennsylvania Trail of History Guide. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2002.

- Reibel, Daniel B., and Mary Lou Golembeski. Selected Reprints from the Harmonie Herald, 1966–1979. Ambridge: Old Economy Village, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1980.

- Reibel, Daniel B., and Patricia B. Reibel. A manual for guides, docents, hostesses, and volunteers of Old Economy. Ambridge, PA: Harmonie Associates, 1974.

- Reibel, Harold B. Readings concerning the Harmony Society in Pennsylvania: Drawn from the accounts of travelers and articles in the Harmonie Herald. Harrisburg, PA, 1978.

- Reichmann, Eberhard, and Ruth Reichmann. The Harmonists: Two Points of View." In Emigration and Settlement Patterns of German Communities in North America, p. 371–380. Eberhard Reichmann, LaVern J. Rippley, and Joerg Nagler, eds. Indianapolis: Max Kade German-American Center, Indiana University–Purdue University, Indianapolis, 1995.

- Ritter, Christine C. "Life in early America, Father Rapp and the Harmony Society." Early American Life 9 (1978): 40–43, 71–72.

- Sasse, Angela. "The Religious Celibate Community in Indiana: Yesterday and Today". In German Influence on Religion in Indiana. Studies in Indiana German Americana Series, Vol. 2, 1995, p. 38–52.

- Schema, Hermann. Gemeinschaftssiedlungen auf religiöser und weltanschaulicher Grundlage. Tübingen, 1969.

- Schneck, J., and Richard Owen. The Rappites: Interesting Notes about Early New Harmony; George Rapp's reform society based on the New Testament. Evansville, IN: Courier Company, 1890.

- Schwab, David, comp. (2010-5-20). "The Harmony Society". U.S. Army Corps of Engineers–Pittsburgh District. 2004-12-3. Retrieved 2012-6-3.

- Slater, Larry R. Ambridge (Pennsylvania). In Images of America. Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia, 2008.

- Stewart, Arthur I., and J. O. Gilbert. Harmony; commemorating the centennial of the Borough of Harmony, Pennsylvania, 1838–1938. Harmony, PA: Stewart, 1938.

- Stewart, Arthur I., and Loran W. Veith. Harmony : commemorating the sesquicentennial of Harmony, Pennsylvania, 1805–1955. Harmony, PA: Stewart, 1955.

- Stockwell, Foster. Encyclopedia of American Communes, 1663–1963. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 1998.

- Straube, Carl Frederick. Rise and Fall of Harmony Society, Economy, PA and Other Poems. Pittsburgh, PA: Press of National Printing Co., 1911.

- Sutton, Robert Paul. Communal Utopias and the American Experience: Religious Communities, 1732–2000. Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 2003.

- Sutton, Robert Paul. Communal Utopias and the American Experience: Secular Communities, 1824–2000. Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 2004.

- Tate, John Matthew. Some notes, pictures and documents relating to the Harmony Society and its homes at Harmony, Pennsylvania, New Harmony, Indiana and Economy, Pennsylvania. Sewickley, PA, 1925.

- Taylor, Anne. Visions of Harmony: A Study of Nineteenth-Century Millenarianism. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

- Thies, Clifford F. "The Success of American Communes." Southern Economic Journal 67, no. 1 (July 2000): 186–199.

- Trahair, Richard C. S. Utopias and Utopians: An Historical Dictionary. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1999.

- Versluis, Arthur. "Western Esotericism and The Harmony Society", Esoterica I, Michigan State University, 1999, pp. 20–47. Retrieved 2012-6-15.

- Wetzel, Richard D. Frontier Musicians on the Connoquenessing, Wabash, and Ohio: A History of the Music and Musicians of George Rapp's Harmony Society (1805–1906). Athens: Ohio University Press, 1976.

- Wetzel, Richard D. "The Music of George Rapp's Harmony Society: 1805–1906." Thesis/diss., University of Pittsburgh, 1970.

- Williams, Aaron. The Harmony Society at Economy, Pennsylvania, Founded by George Rapp, A.D. 1805. Pittsburgh: W.S. Haven, 1866.

- Wilson, William E. The Angel and the Serpent: The Story of New Harmony. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1964.

- Young, Marguerite. Angel in the Forest: A Fairy Tale of Two Utopias. [Fiction]. New York: Reynal and Hitchcock, 1945.

- Young, Norman C. Old Economy-Ambridge sesqui-centennial historical booklet. Ambridge, PA: The Committee, 1974.

External links

- Old Economy Village museum in Old Economy, Pennsylvania, administered by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, interpreting the history of the Harmony Society.

- The Harmony Museum of Harmony, Pennsylvania, operated by Historic Harmony, Inc.

- Historic New Harmony of New Harmony, Indiana, administered by the University of Southern Indiana and the Indiana State Museum and Historic Sites.

- Harmony Society Papers, PA State Archives

- Account of the Harmony Society and its beliefs

- The Harmonist Labyrinths

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- John M. Tate, Jr. Collection of Notes, Pictures and Documents relating to the Harmony Society, 1806-1930, DAR.1946.02, Darlington Library, Special Collections Department, University of Pittsburgh