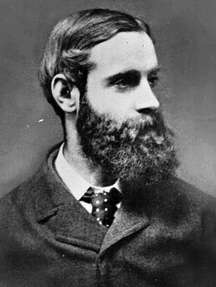

Randolph Caldecott

Randolph Caldecott (/ˈkɔːldəˌkɑːt/;[1] 22 March 1846 – 12 February 1886) was an English artist and illustrator, born in Chester. The Caldecott Medal was named in his honour. He exercised his art chiefly in book illustrations. His abilities as an artist were promptly and generously recognised by the Royal Academy. Caldecott greatly influenced illustration of children's books during the nineteenth century. Two books illustrated by him, priced at a shilling each, were published every Christmas for eight years.

Randolph Caldecott | |

|---|---|

Randolph Caldecott | |

| Born | Randolph Caldecott 22 March 1846 Chester, England |

| Died | 12 February 1886 (aged 39) St. Augustine, Florida, U.S. |

| Nationality | English |

| Education | Manchester School of Art |

| Known for | Children's illustration |

Notable work | The House That Jack Built The Diverting History of John Gilpin Three Jovial Huntsmen A Frog He Would A-Wooing Go |

Caldecott also illustrated novels and accounts of foreign travel, made humorous drawings depicting hunting and fashionable life, drew cartoons and he made sketches of the Houses of Parliament inside and out, and exhibited sculptures and paintings in oil and watercolour in the Royal Academy and galleries.

Early life

Caldecott was born at 150 Bridge Street (now No 16), Chester,[2] where his father, John Caldecott, was an accountant, twice married with thirteen children. Caldecott was his father’s third child by his first wife, Mary Dinah Brookes. In 1848, the family moved to Challoner House, Crook Street, Chester, and in 1860 to 23 Richmond Place, Boughton, a village just outside the city.[2]

From his early childhood, Caldecott drew and modelled, mostly animals. His main education came with five years at the King's School, Chester, a grammar school then in the cathedral precinct in the city centre, which he left at the age of fifteen. In that same year, 1861, he first had a drawing published, a sketch of a disastrous fire at the Queens Railway Hotel in Chester, which appeared in the Illustrated London News, together with his account of the blaze.[2]

On leaving school, Caldecott went to work as a clerk at the offices of the Whitchurch & Ellesmere Bank in Whitchurch, Shropshire, and took lodgings at Wirswall, a village near the town. When he was out on errands, he was either walking or riding around the countryside, and many of his later illustrations incorporate buildings and scenery of Cheshire and that part of Shropshire.[2]

Caldecott’s love of riding led him to take up fox hunting, and his experiences in the hunting field and his love of the chase bore fruit over the years in a mass of drawings and sketches of hunting scenes, many of them humorous.[2]

Manchester

After six years at Whitchurch, Caldecott moved to the head office in Manchester of the Manchester & Salford Bank. He lodged variously in Aberdeen Street, Rusholme Grove and at Bowdon. He took the opportunity to study at night school at the Manchester School of Art and practised continually, with success in local papers and some London publications. It was a habit of his at this time, which he maintained all his life, to decorate his letters, papers and documents of all descriptions with marginal sketches to illustrate the content or provide amusement. A number of his letters have been reprinted with their illustrations in Yours Pictorially, a book edited by Michael Hutchings. In 1870, a painter friend in London, Thomas Armstrong, put Caldecott in touch with Henry Blackburn, the editor of London Society, who published a number of his drawings in several issues of the monthly magazine.

London

Encouraged by this evidence of his ability to support himself by his art, Caldecott decided to quit his job and move to London; this he did in 1872 at the age of 26. Within two years he had become a successful magazine illustrator working on commission. His work included individual sketches, illustrations of other articles and a series of illustrations of a holiday which he and Henry Blackburn took in the Harz Mountains in Germany. The latter became the first of a number of such series.

He remained in London for seven years, spending most of them in lodgings at 46 Great Russell Street just opposite the British Museum, in the heart of Bloomsbury. While there he met and made friends (as he did very readily) with many artistic and literary people, among them Dante Gabriel Rossetti, George du Maurier (who was a fellow contributor to Punch), John Everett Millais and Frederic Leighton. His friendship with Frederic (later Lord) Leighton led to a commission to design peacock capitals for four columns in the Arab room at Leighton's rather exotic home, Leighton House in Kensington. (Walter Crane designed a tiled peacock frieze for the same room.)

In 1869 Caldecott exhibited a picture in the Royal Manchester Institute. He had a picture exhibited in the Royal Academy for the first time in 1876. He was also a watercolourist and was elected to the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours in 1882.

In 1877 Edmund Evans, who was a leading colour printer using coloured woodblocks, lost the services of Walter Crane as his children's book illustrator and asked Caldecott for illustrations for two Christmas books. The results were The House that Jack Built and The Diverting History of John Gilpin, published in 1878. They were an immediate success; so much so that Caldecott produced two more each year for Evans until he died. Many of Evans’ original printing blocks survive and are held at St Bride Library in London. The stories and rhymes were all of Caldecott's choosing and in some cases were written or added to by himself. In another milieu Caldecott followed The Harz Mountains with illustrations for two books by Washington Irving, three for Juliana Ewing, another of Henry Blackburn's, one for Captain Frederick Marryat and for other authors. Among well known admirers of his work were Gauguin and Van Gogh.

Randolph continued to travel, partly for the sake of his health, and to make drawings of the people and surroundings of the places he visited; these drawings were accompanied by humorous and witty captions and narrative.

Marriage

In 1879 he moved to Wybornes, a house near Kemsing in Kent. It is there that he became engaged to Marian Brind, who lived at Chelsfield about seven miles away. They were married on 18 March[4] 1880 and lived at Wybornes for the next two years. There were no children of the marriage. In the autumn of 1882 the Caldecotts left Kent and bought a house, Broomfield, at Frensham in Surrey; they also rented No 24 Holland Street, Kensington. By 1884, sales of Caldecott's Nursery Rhymes had reached 867,000 copies (of twelve books) and he was internationally famous.

Death

Caldecott's health was generally poor and he suffered much from gastritis and a heart condition going back to an illness in his childhood. It was his health among other things which prompted his many winter trips to the Mediterranean and other warm climates. It was on such a tour in the United States of America in 1886 that he was taken ill again and died. He and Marian had sailed to New York and travelled to Florida in an unusually cold February; Randolph was taken ill and died at St. Augustine. He was not quite 40 years old. A headstone marks his grave in the cemetery there.

Soon after his early death, his many friends contributed to a memorial, which was designed by Sir Alfred Gilbert. It was placed in the crypt of St Paul's Cathedral, London. There is also a memorial to him in Chester Cathedral.

Appreciation

Gleeson White wrote of Caldecott:

Caldecott was a fine literary artist, who was able to express himself with rare facility in pictures in place of words, so that his comments upon a simple text reveal endless subtleties of thought ... You have but to turn to any of his toy-books to see that at times each word, almost each syllable, inspired its own picture ... He studied his subject as no one else ever studied it ... Then he portrayed it simply and with inimitable vigor, with a fine economy of line and colour; when colour is added, it is mainly as a gay convention, and not closely imitative of nature.

G. K. Chesterton wrote in a Caldecott picture book that he presented to a young friend:

- This is the sort of book we like

- (For you and I are very small),

- With pictures stuck in anyhow,

- And hardly any words at all.

- . . .

- You will not understand a word

- Of all the words, including mine;

- Never you trouble; you can see,

- And all directness is divine—

- Stand up and keep your childishness:

- Read all the pedants’ screeds and strictures;

- But don’t believe in anything

- That can’t be told in coloured pictures.[5]

For Maurice Sendak "Caldecott's work heralds the beginning of the modern picture book. He devised an ingenious juxtaposition of picture and word, a counterpoint that never happened before. Words are left out—but the picture says it. Pictures are left out—but the word says it." Sendak also appreciated the subtle darkness of Caldecott's work: "You can't say it's a tragedy, but something hurts. Like a shadow passing quickly over. It is this which gives a Caldecott book—however frothy the verses and pictures—its unexpected depth."[6]

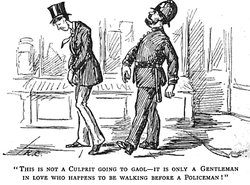

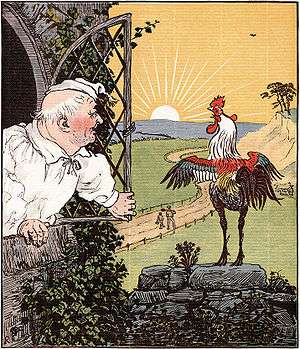

Gallery of images from Caldecott's toy books

Cover of Babes in the Wood

Cover of Babes in the Wood "The lasses held the stakes" – from Come Lasses and Lads

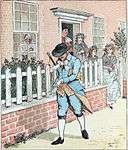

"The lasses held the stakes" – from Come Lasses and Lads "In Islington there lived a man/Of whom the world might say/That still a godly race he ran" – illustration from Oliver Goldsmith's An Elegy of the Death of a Mad Dog

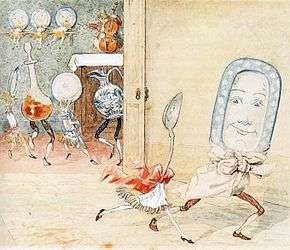

"In Islington there lived a man/Of whom the world might say/That still a godly race he ran" – illustration from Oliver Goldsmith's An Elegy of the Death of a Mad Dog "The dish ran away with the spoon" – this image shows movement characteristic of Caldecott's illustrations

"The dish ran away with the spoon" – this image shows movement characteristic of Caldecott's illustrations

Bibliography

- Caldecott's 16 picture books[7]

- The House that Jack Built (1878)

- John Gilpin (1878)

- Elegy on a Mad Dog (1879)

- The Babes in the Wood (1879)

- The Three Jovial Huntsmen (1880)

- Sing a Song of Sixpence (1880)

- The Queen of Hearts (1881)

- The Milk-Maid (1882)

- Hey-Diddle-Diddle and Baby Bunting (1882)

- The Fox Jumps Over the Parson's Gate (1883)

- A Frog He Would A-Wooing Go (1883)

- Come, Lasses, and Lads (1884)

- Ride A-Cock Horse to Branbury Cross & A Farmer went Trotting Upon his Grey Mare (1884)

- Mrs. Mary Blaze (1885)

- The Great Panjandrum Himself (1885)

- Complete Collection of Pictures and Songs (1887) From the Collections at the Library of Congress

See also

- Caldecott Community, a pioneering school for working class and vulnerable children founded in 1911 and named after Randolph Caldecott

References

- "Caldecott, Randolph". Webster's New World Dictionary, Wiley Publishing, Inc., 2010.

- James Hamilton (23 September 2004). "Caldecott, Randolph (1846–1886)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/4365.

- Blackburn (1890), 10

- In a postscript to a letter dated 17 March 1880 from Caldecott to Victorian poet Frederick Locker-Lampson he says "I am to be wed tomorrow 18th"

- Alfred George Gardiner, "Prophets, Priests and Kings", Alston Rivers Ltd., 1908, p. 327

- "Caldecott, Randolph 1846–1886". Children's Literature Review. 2005. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016.

- Henry Blackburn (1886). Randolph Caldecott: a personal memoir of his early art career : with one hundred and seventy-two illustrations. S. Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington. p. 212. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

Sources and further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Randolph Caldecott. |

- Blackburn, Henry. Randolph Caldecott: A Memoir of his Early Art Career. London: Low, Marston, Searle & Livingtston. 1890.

- Engen, Rodney K. Randolph Caldecott: Lord of the Nursery (London: Bloomsbury Pub., 1988). ISBN 1-870630-45-9

- Brian Alderson, Sing a Song for Sixpence: The English Picture Book Tradition and Randolph Caldecott (1987)

- Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1886). . Dictionary of National Biography. 8. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 239–40.

- Ray, Gorden Norton. The Illustrator and the Book in England from 1790 to 1914. Courier Dover. 1991. ISBN 978-0-486-26955-9

- Maurice Sendak, Caldecott & Co.: Notes on Books and Pictures (1988)

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Caldecott, Randolph. |

- R. Caldecott online (ArtCyclopedia)

- Online collections

- Works by Randolph Caldecott at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Randolph Caldecott at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Randolph Caldecott at Internet Archive

- Works by Randolph Caldecott at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Randolph Caldecott at the University of Florida's "Baldwin Library of Historical Children's Literature" (color illustrated scanned books).

- Randolph Caldecott in Manchester Art Gallery

- Miscellaneous