Plectrum

A plectrum is a small flat tool used to pluck or strum a stringed instrument. For hand-held instruments such as guitars and mandolins, the plectrum is often called a pick and is a separate tool held in the player's hand. In harpsichords, the plectra are attached to the jack mechanism.

Wielded by hand

Guitars and similar instruments

A plectrum for electric guitars, acoustic guitars, bass guitars and mandolins is typically a thin piece of plastic or other material shaped like a pointed teardrop or triangle. The size, shape and width may vary considerably. Banjo and guitar players may wear a metal or plastic thumb pick mounted on a ring, and bluegrass banjo players often wear metal or plastic fingerpicks on their fingertips. Guitarists also use fingerpicks.

Guitar picks are made of a variety of materials, including celluloid, metal, and rarely other exotic materials such as turtle shell, but today delrin is the most common . For other instruments in the modern day most players use plastic plectra but a variety of other materials, including wood and felt (for use with the ukulele) are common. Guitarists in the rock, blues, jazz and bluegrass genres tend to use a plectrum, partly because the use of steel strings tends to wear out the fingernails quickly, and also because a plectrum provides a more "focused" and "aggressive" sound. Many guitarists also use the pick and the remaining right-hand fingers simultaneously to combine some advantages of flat-picking and finger picking. This technique is called hybrid picking.

A plectrum of the guitar type is often called a pick (or a flatpick to distinguish it from fingerpicks).

Non-Western instruments

The plectra for the Japanese biwa and shamisen can be quite large, and those used for the Arabic oud are longer and narrower, replacing the formerly used eagle feather. Plectra used for Chinese instruments such as the sanxian were formerly made of animal horn, though many players today use plastic plectra.

Plectra from around the world

In harpsichords

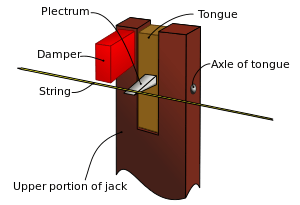

In a harpsichord, there is a separate plectrum for each string. These plectra are very small, often only about 10 millimeters long, about 1.5 millimeters wide, and half a millimeter thick. The plectrum is gently tapered, being narrowest at the plucking end. The top surface of the plectrum is flat and horizontal and is held in the tongue of the jack, which permits it to pluck moving upward and pass almost silently past the string moving downward.

In the historical period of harpsichord construction (up to about 1800) plectra were made of sturdy feather quills, usually from crows or ravens. In Italy, some makers (including Bartolomeo Cristofori) used vulture quills.[1] Other Italian harpsichords employed plectra of leather.[2] In late French harpsichords by the great builder Pascal Taskin, peau de buffle, a chamois-like material from the hide of the European bison, was used for plectra to produce a delicate pianissimo.[2]

Modern harpsichords frequently employ plectra made with plastic, specifically the plastic known as acetal. Some plectra are of the homopolymer variety of acetal, sold by DuPont under the name "Delrin", while others are of the copolymer variety, sold by Ticona as "Celcon".[3] Harpsichord technicians and builders generally use the trade names to refer to these materials. In either of its varieties, acetal is far more durable than quill, which cuts down substantially on the time that must be spent in voicing (see below).[4]

Several contemporary builders and players[5] have reasserted the superiority of bird quill for high-level harpsichords. While the difference in sound between acetal and quill is acknowledged to be small,[6] what difference may exist is held to be to the advantage of quill. In addition, quill plectra are observed to fail gradually, giving warning by the diminishing volume, whereas acetal plectra fail suddenly and completely, sometimes in the middle of a performance.

Voicing harpsichord plectra

The plectra of a harpsichord must be cut precisely, in a process called "voicing". A properly voiced plectrum will pluck the string in a way that produces a good musical tone and matches well in loudness with all of the other strings. The underside of the plectrum must be appropriately slanted and entirely smooth, so that the jack will not "hang" (get caught on the string) when, after sounding a note, it is moved back down below the level of the string.

Normally, voicing is carried out by inserting the plectrum into the jack, then placing the jack on a small wooden voicing block, so that the top of the plectrum sits flush with the block. The plectrum is then cut and thinned on the underside with a small, very sharp knife, such as an X-Acto knife.[7] As the plectrum is progressively trimmed, its jack is replaced in the instrument at intervals to test the result for loudness, tone quality, and the possibility of hanging.

Voicing is a refined skill, carried out fluently by professional builders, but one that usually must also be learned (at least to some degree) by harpsichord owners.[8]

Etymology and usage

First attested in English 15th century,[9] the word "plectrum" comes from Latin plectrum, itself derived from Greek πλῆκτρον[10] (plēktron), "anything to strike with, an instrument for striking the lyre, a spear point".[11][12]

"Plectrum" has both a Latin-based plural, plectra and a native English plural, plectrums. Plectra is used in formal writing, particularly in discussing the harpsichord as an instrument of classical music,[13] while plectrums is more common in ordinary speech.

Notes

- Jensen 1998, 85. Not all bird species suffice; Wolfgang Zuckermann observed in 1969 that "quill from birds such as goose or chicken have given this material a bad name, since feathers from these fowl are not satisfactory for the purpose." Aside from crow and raven, he mentions condor, eagle and turkey as good sources for plectra. See Wolfgang Zuckermann (1969): The Modern Harpsichord, New York, October House, p. 61.

- Hubbard 1967

- For a discussion of these plastics, see .

- This reflects what is probably the mainstream view; however, the builder Grant O'Brien has suggested that if cut properly, a quill plectrum will last indefinitely, and he mentions harpsichords from the historical period whose quills have lasted intact to the present. The correct form of voicing, O'Brien suggests, involves tapering, so that a plectrum will display constant curvature at the moment it is maximally displaced in plucking. Source:

- Hendrik Broekman (), Tilman Skowroneck (), Keith Hill ().

- See Skowroneck, op. cit., Broekman, op. cit., and for a particularly skeptical view O'Brien, .

- Kottick (1987)

- Source for all of this section: Kottick (1987)

- Oxford English Dictionary, online edition (www.oed.com)

- Oxford English Dictionary

- πλῆκτρον, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- Greek "πλῆκτρον" comes from the verb "πλήττω" or "πλήσσω" (plēssō), "to hit, to strike, to smite, to sting". πλήσσω, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- The affiliation of "plectra" and "plectrums" with harpsichords and guitars, respectively, is vividly discussed by Guardian columnist James Fenton: .

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Plectrum. |

- Hubbard, Frank (1967) Three Centuries of Harpsichord Making. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Jensen, David P. (1998) "A Florentine Harpsichord: Revealing a Transitional Technology" Early Music, February issue, pp. 71–85.

- Kottick, Edward L. (1987) The Harpsichord Owner's Guide. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.