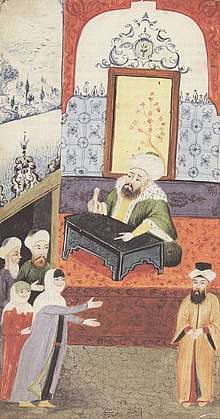

Qadi

A Qadi (Arabic: قاضي, romanized: Qāḍī; also Qazi, cadi, kadi or kazi) is the magistrate or judge of a Shariʿa court, who also exercises extrajudicial functions, such as mediation, guardianship over orphans and minors, and supervision and auditing of public works.[1]

History

The term "qadi" was in use from the time of Muhammad and remained the term used for judges throughout Islamic history and the period of the caliphates. While the muftis and fuqaha played the role in elucidation of the principles of jurisprudence and the laws, the qadi remained the key person ensuring the establishment of justice on the basis of these very laws and rules. Thus, the qadi was chosen from amongst those who had mastered the sciences of jurisprudence and law. In constructing their legal doctrine, these legal scholars took as their point of departure the precedents already established by the qadis.

During the period of the Abbasid Caliphate, the office of the qadi al-qudat (Chief Justice of the Highest Court) was established. Among the most famous of the early qadi al-qudat was Qadi Abu Yusuf who was a disciple of the famous early jurist Abu Hanifa.[2]

The office of the qadi continued to be a very important one in every principality of the caliphates and sultanates of the Muslim empires over the centuries. The rulers appointed qadis in every region, town and village for judicial and administrative control and to establish peace and justice over the dominions they controlled.

The Abbasids created the office of chief qadi (qāḍī al-quḍāh, sometimes romanized as Qadi al-Quda), whose holder acted primarily as adviser to the caliph in the appointment and dismissal of qadis[3]. Later Islamic states generally retained this office, while granting to its holder the authority to issue appointments and dismissals in his own name. The Mamluk state, which ruled Egypt and Syria from 1250 to 1516 CE, introduced the practice of appointing four chief qadis, one for each of the Sunni legal schools (madhhabs).

Although the primary responsibility of a qadi was a judicial one, he was generally charged with certain nonjudicial responsibilities as well, such as the administration of religious endowments (waqfs), the legitimization of the accession or deposition of a ruler, the execution of wills, the accreditation of witnesses, guardianship over orphans and others in need of protection, and supervision of the enforcement of public morals (ḥisbah).[4]

Functions

A qadi is a judge responsible for the application of Islamic positive law (fiqh). The office originated under the rule of the first Umayyad caliphs (AH 40–85/661–705 CE), when the provincial governors of the newly created Islamic empire, unable to adjudicate the many disputes that arose among Muslims living within their territories, began to delegate this function to others[5]. In this early period of Islamic history, no body of Islamic positive law had yet come into existence, and the first qadis therefore decided cases on the basis of the only guidelines available to them: Arab customary law, the laws of the conquered territories, the general precepts of the Qurʾān, and their own sense of equity.

During the later Umayyad period (705–750 CE), a growing class of Muslim legal scholars, distinct from the qadis, busied themselves with the task of supplying the needed body of law, and by the time of the accession to power of the Abbasid dynasty in 750 their work could be said to have been essentially completed. In constructing their legal doctrine, these legal scholars took as their point of departure the precedents already established by the qadis, some of which they rejected as inconsistent with Islamic principles as these were coming to be understood, but most of which they adopted, with or without modification. Thus the first qadis in effect laid the foundations of Islamic positive law. Once this law had been formed, however, the role of the qadi underwent a profound change. No longer free to follow the guidelines mentioned above, a qadi was now expected to adhere solely to the new Islamic law, and this adherence has characterized the office ever since.

A qadi continued, however, to be a delegate of a higher authority, ultimately the caliph or, after the demise of the caliphate, the supreme ruler in a given territory. This delegate status implies the absence of a separation of powers; both judicial and executive powers were concentrated in the person of the supreme ruler (caliph or otherwise)[6]. On the other hand, a certain degree of autonomy was enjoyed by a qadi in that the law that he applied was not the creation of the supreme ruler or the expression of his will. What a qadi owed to the supreme ruler was solely the power to apply the law, for which sanctions were necessary that only the supreme ruler as head of the state could guarantee.

Qadi versus mufti

Similar to a qadi, a mufti is also an interpreting power of Shari'a law. Muftis are jurists that give authoritative legal opinions, or fatwas, and historically have been known to rank above qadis. [7] With the introduction of the secular court system in the 19th century, Ottoman councils began to enforce criminal legislation, in order to emphasize their position as part of the new executive. This creation of the hierarchical secular judiciary did not displace the original Shari'a courts.

Shari'a justice developed along lines comparable to what happened to the organization of secular justice: greater bureaucratization, more precise legal circumscription of jurisdiction, and the creation of a hierarchy. This development began in 1856.

Until the Qadi’s Ordinance of 1856, the qadis were appointed by the Porte and were part of the Ottoman religious judiciary. This Ordinance recommends the consultation of muftis and 'ulama' . In practice, the sentences of qadis usually were checked by muftis appointed to the courts. Other important decisions were also checked by the mufti of the Majlis al-Ahkdm or by a council of 'ulama' connected with it. It is said that if the local qadi and mufti disagreed, it became customary to submit the case to the authoritative Grand Mufti.

Later, in 1880, the new Shari'a Courts Ordinance introduced the hierarchical judiciary. Through the Ministry of Justice, parties could appeal to the Cairo Shari'a Court against decisions of provincial qadis and ni'ibs. Here, parties could appeal to the Shari’a Court open to the Shaykh al-Azhar and the Grand Mufti, where other people could be added.

Lastly, judges were to consult the muftis appointed to their courts whenever a case was not totally clear to them. If the problem was not solved, the case had to be submitted to the Grand Mufti, whose fatwa was binding on the qadi. [8]

Qualifications

A qadi must be an adult. They must be free, a Muslim, sane, unconvicted of slander and educated in Islamic science.[4] Their performance must be totally congruent with Sharia without using their own interpretation. In a trial in front of a qadi, it is the plaintiff who is responsible for bringing evidence against the defendant in order to have him or her convicted. There are no appeals to the judgements of a qadi.[9] A qadi must exercise his office in a public place, the chief mosque is recommended, or, in their own house, where the public should have free access.[10] The quadi had authority over a territory whose diameter was equivalent to a day's walk[11]. The opening of a trial theoretically required the presence of both the plaintiff and the defendant. If a plaintiff's adversary resided in another judicial district, the plaintiff could present his evidence before the qadi of his own district. This qadi would then write to the judge of the district in which the defendant resided, exposing the evidence against him. The addressee qadi summoned the defendant and convicted him on that basis[12]. Qadis kept court records in their archives (diwan) and handed them over to their successors once they had been dismissed[13].

Qadis must not receive gifts from participants in trials and they must be careful in engaging themselves in trade. Despite the rules governing the office, Muslim history is full of complaints about qadis. It has often been a problem that qadis have been managers of waqfs, religious endowments.

The qualifications that a qadi must possess are stated in the law, although the law is not uniform on this subject. The minimal requirement upon which all the jurists agree is that a qadi possess the same qualifications as a witness in court, that is, that they be free, sane, adult, trustworthy, and a Muslim. Some require that they also possess the qualifications of a jurist, that is, that they be well versed in the law, while others regard those qualifications as simply preferable, implying that a person may effectively discharge the duties of the office without being well versed in the law. This latter position presupposed that a qadi who is not learned in matters of law would consult those who are before reaching a decision. Indeed, consultation was urged upon the learned qadi as well, since even the learned are fallible and can profit from the views of others. Those consulted did not, however, have a voice in the final decision making. The Islamic court was a strictly one-judge court and the final decision rested upon the shoulders of a single qadi.

Jurisdiction

The jurisdiction of a qadi was theoretically coextensive with the scope of the law that he applied. That law was fundamentally a law for Muslims, and the internal affairs of the non-Muslim, or dhimmīs, communities living within the Islamic state were left under the jurisdictions of those communities[14]. Islamic law governed dhimmīs only with respect to their relations to Muslims and to the Islamic state. In actual practice, however, the jurisdiction of a qadi was hemmed in by what must be regarded as rival jurisdictions, particularly that of the maẓālim court and that of the shurṭah.

The maẓālim was a court (presided over by the supreme ruler himself or his governor) that heard complaints addressed to it by virtually any offended party. Since Islamic law did not provide for any appellate jurisdiction but regarded the decision of a qadi as final and irrevocable, the maẓālim court could function as a kind of court of appeals in cases where parties complained of unfair decisions from qadis. The maẓālim judge was not bound to the rules of Islamic law (fiqh), nor for that matter was he bound to any body of positive law, but was free to make decisions entirely on the basis of considerations of equity. The maẓālim court thus provided a remedy for the inability of a qadi to take equity freely into account. It also made up for certain shortcomings of Islamic law, for example, the lack of a highly developed law of torts, which was largely due to the preoccupation of the law with breaches of contracts. In addition, it heard complaints against state officials[15].

The shurṭah, on the other hand, was the state apparatus responsible for criminal justice. It too provided a remedy for a deficiency in the law, namely the incompleteness and procedural rigidity of its criminal code. Although in theory a qadi exercised a criminal jurisdiction, in practice this jurisdiction was removed from his sphere of competence and turned over entirely to the shurṭah, which developed its own penalties and procedures. What was left to the qadi was a jurisdiction concerned mainly with cases having to do with inheritance, personal status, property, and commercial transactions. Even within this jurisdiction, a particular qadi's jurisdiction could be further restricted to particular cases or types of cases at the behest of the appointing superior.

The principle of delegation of judicial powers not only allowed the supreme ruler to delegate these powers to a qadi; it also allowed qadis to further delegate them to others, and there was in principle no limit to this chain of delegation. All persons in the chain, except for the supreme ruler or his governor, bore the title qadi. Although in theory the appointment of a qadi could be effected by a simple verbal declaration on the part of the appointing superior, normally it was accomplished by means of a written certificate of investiture, which obviated the need for the appointee to appear in the presence of the superior. The appointment was essentially unilateral rather than contractual and did not require acceptance on the part of the appointee in order to be effective. It could be revoked at any time.

Jewish use

The Jews living in the Ottoman Empire sometimes used qadi courts to settle disputes. Under the Ottoman system, Jews throughout the Empire retained the formal right to oversee their own courts and apply their own religious law. The motivation for bringing Jewish cases to qadi courts varied. In sixteenth-century Jerusalem, Jews preserved their own courts and maintained relative autonomy. Rabbi Samuel De Medina and other prominent rabbis repeatedly warned co-religionists that it was forbidden to bring cases to government courts and that doing so undermined Jewish legal authority, which could be superseded only "in matters that pertained to taxation, commercial transactions, and contracts".[16]

Throughout the century, Jewish litigants and witnesses participated in Muslim court proceedings when it was expedient, or when cited to do so. Jews who wanted to bring cases against Muslims had to do so in qadi courts, where they found a surprising objectivity. But the different legal status of Jews and Muslims was preserved. Jewish testimony was weighted differently when the testimony was prejudicial to Jews or Muslims.[17]

In Sri Lanka

In accordance with section 12 of the Muslim Marriage and Divorce Act, the Judicial Services Commission may appoint any male Muslim of good character and position and of suitable attainments to be a Quazi. The Quazi does not have a permanent courthouse, thus the word "Quazi Court" is not applicable in the current context. The Quazi can hear the cases anywhere and anytime he wants. Currently most Quazis are laymen.

In accordance with section 15 of the Muslim Marriage and Divorce Act, the Judicial Services Commission may appoint a Board of Quazis, consisting of five male Muslims resident in Sri Lanka, who are of good character and position and of suitable attainments, to hear appeals from the decisions of the Quazis under this Act. The Board of Quazis does not have a permanent courthouse either. Usually an appeal or a revision takes a minimum of two to three years in order to arrive for judgment from the Board of Quazis. The Board of Quazis can start the proceedings at whatever time they want and end the proceedings at whatever time they want. The Office of the Board of Quazis is situated in Hulftsdorp, Colombo 12.

Muslim Female Judges

Post-Colonialism and Female Judges

As Muslim states gained independence from Europe, a vacuum was intentionally left by the colonizing powers in various sectors of education and government. European colonizers were careful to exclude "natives" from access to legal education and legal professions.[18] Thus, the number of law graduates and legal professionals was inadequate, and women were needed to fill the empty spaces in the judiciaries. Rulers reacted by expanding general educational opportunities for women to fill positions in the expanding state bureaucracy, and in the 1950s and 1960s began the first phase of women being appointed as judges. Such was the case in 1950s Indonesia, which has the largest number of female judges in the Muslim world.[19]

In some countries the colonized had more opportunities to study law, such as in Egypt. Sufficient male students to study law and fill legal positions and other bureaucratic jobs in the postcolonial state may have delayed women's acceptance into judicial positions.[19]

In comparison, a similar situation happened in Europe and America. After World War II, a shortage of judges in Europe paved the way for European women to enter legal professions and work as judges.[20] American women in World War II also entered the workforce in unprecedented numbers due to the dire need.

Contemporary Female Judges in Muslim States

Although the role of qadi has traditionally been restricted to men, women now serve as qadis in many countries, including Egypt, Jordan, Malaysia, Palestine, Tunisia, Sudan, and the United Arab Emirates.[21] In 2009, two women were appointed as qadis by the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank.[19] In 2010, Malaysia appointed two women as qadis as well. However, it was decided that as women they may only rule over custody, alimony, and common property issues, not over criminal or divorce cases, which usually make up most of a qadi's work.[22] In Indonesia, there are nearly 100 female qadis.[22] In 2017, Hana Khatib was appointed as the first female qadi in Israel.[23]

In Morocco, a researcher found that female judges were more sensitive to the interests of female litigants in alimony cases and held similar views to their male colleagues in maintaining Shari'a standards such as the need for a wali (male guardian) for marriage.[24][19]

Scholarly Debate

There is disagreement among Islamic scholars as to whether women are qualified to act as qadis or not. Many modern Muslim states have a combination of religious and secular courts. The secular courts often have little issue with female judges, but the religious courts may restrict what domains female judges can preside in, such as only family and marital law.[19]

Local usage

Muslim Region

The rulers of Muslim IndoPak also used the same institution of the qadi (or qazi). The qadi was given the responsibility for total administrative, judicial and fiscal control over a territory or a town. He would maintain all the civil records as well. He would also retain a small army or force to ensure that his rulings are enforced.

In most cases, the qazi would pass on the title and position to his son, descendant or a very close relative. Over the centuries, this profession became a title within the families, and the power remained within one family in a region. Throughout Muslim Regions, we now find various Qazi families who descended through their famous Qazi (Qadi) ancestors and retained the lands and position. Each family is known by the town or city that their ancestors controlled. Qazis are mostly found in areas of Pakistan, specifically in Sindh. They are now also prominent in small areas of Australia.

Mayotte governorship

On the island of Mayotte, one of the Comoro Islands, the title qadi was used for Umar who governed it from 19 November 1835 to 1836 after its conquest by and annexation to the Sultanate of Ndzuwani (Anjouan).[25]

Songhai Empire

In the Songhai Empire, criminal justice was based mainly, if not entirely, on Islamic principles, especially during the rule of Askia Muhammad. The local qadis were responsible for maintaining order by following Sharia law according to the Qur'an. An additional qadi was noted as a necessity in order to settle minor disputes between immigrant merchants.[26] Qadis worked at the local level and were positioned in important trading towns, such as Timbuktu and Djenné. The Qadi was appointed by the king and dealt with common-law misdemeanors according to Sharia law. The Qadi also had the power to grant a pardon or offer refuge.[27]

Spanish derivation

Alcalde, one of the current Spanish terms for the mayor of a town or city, is derived from the Arabic al-qaḍi ( ال قاضي), "the judge". In Al-Andalus a single qadi was appointed to each province. To deal with issues that fell outside of the purview of sharia or to handle municipal administration (such as oversight of the police and the markets) other judicial officers with different titles were appointed by the rulers.[28]

The term was later adopted in Portugal, Leon and Castile during the eleventh and twelfth centuries to refer to the assistant judges, who served under the principal municipal judge, the iudex or juez. Unlike the appointed Andalusian qadis, the alcaldes were elected by an assembly of the municipality's property owners.[29] Eventually the term came to be applied to a host of positions that combined administrative and judicial functions, such as the alcaldes mayores, the alcaldes del crimen and the alcaldes de barrio. The adoption of this term, like many other Arabic ones, reflects the fact that, at least in the early phases of the Reconquista, Muslim society in the Iberian Peninsula imparted great influence on the Christian one. As Spanish Christians took over an increasing part of the Peninsula, they adapted Muslim systems and terminology for their own use.[30]

Ottoman Empire

In the Ottoman Empire, qadis were appointed by the Veliyu l-Emr. With the reform movements, secular courts have replaced qadis, but they formerly held wide-ranging responsibilities:

- ... During Ottoman period, [qadi] was responsible for the city services. The charged people such as Subasi, Bocekbasi, Copluk Subasisi, Mimarbasi and Police assisted the qadi, who coordinated all the services." [From History of Istanbul Municipality, Istanbul Municipality (in Turkish).]

The role of the Qadi in the Ottoman legal system changed as the Empire progressed through history. The 19th century brought a great deal of political and legal reform to the Ottoman Empire in an effort to modernize the nation in the face of a shifting power balance in Europe and the interventions in Ottoman territories that followed. In territories such as the Khedivate of Egypt, attempts were made at merging the existing Hanafi system with French-influenced secular laws in an attempt to reduce the influence of local Qadis and their rulings.[31] Such efforts were met with mixed success as the Ottoman-drafted reforms often still left fields such as civil law open to a Qadi's rulings based on the previously used Hanafi systems in sharia-influenced courts. [32]

In the Ottoman Empire, a Kadiluk – the district covered by a kadı – was an administrative subdivision, smaller than a Sanjak. [33]

Expansion of the use of qadis

As the Empire expanded, so did the legal complexities that were built into the system of administration carried over and were enhanced by the conditions of frontier expansion. In particular, the Islamic empire adapted legal devices to deal with the existence of large populations of non-Muslims, a persistent feature of empire despite incentives for conversion and in part because of institutional protections for communal legal forums. These aspects of the Islamic legal order would have been quite familiar to travelers from other parts of the world. Indeed, Jewish, Armenian, and Christian traders found institutional continuity across Islamic and Western regions, negotiating for and adopting strategies to enhance this resemblance.[34]

See also

- Ibn Battuta

- Cadilesker

- Islamic law

- Kadiluk, Ottoman administrative unit ruled by a Kadi

- List of Islamic terms in Arabic

- Tel el-Qadi, ("Mound of the Judge"), Arabic name of Tel Dan, Israel

- Thumal the qahraman

- Qadiyat

- Kadhi courts, special for civil law matters among Muslims in Kenya

References

- B. Hallaq, Wael (2009). An Introduction to Islamic law. Oxford University Press. pp. 175–6. ISBN 9780521678735.

- Zubaida, Sami (2005-07-08). Law and Power in the Islamic World. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9781850439349.

- Tillier, Mathieu (2009-12-05), "I - Le grand cadi", Les cadis d'Iraq et l'État Abbasside (132/750-334/945), Études arabes, médiévales et modernes, Damascus: Presses de l’Ifpo, pp. 426–461, ISBN 978-2-35159-278-6

- "qadi | Muslim judge". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2017-09-12.

- Tillier, Mathieu (2009-12-05), "I - De La Mecque aux amṣār : aux origines du cadi", Les cadis d'Iraq et l'État Abbasside (132/750-334/945), Études arabes, médiévales et modernes, Damascus: Presses de l’Ifpo, pp. 63–96, ISBN 978-2-35159-278-6

- Tillier, Mathieu (2014-05-04). "Judicial Authority and Qāḍī s' Autonomy under the ʿAbbāsids". Al-Masāq. 26 (2): 119–131. doi:10.1080/09503110.2014.915102. ISSN 0950-3110.

- William L. Cleveland, Martin Bunton (2016). A History of the Modern Middle East. Westview Press. p. 561.

- Peters, Rudolph. "Islamic and Secular Criminal Law in Nineteenth Century Egypt: The Role and Function of the Qadi". Islamic Law and Society 4, no. 1 (1997): 70–90.

- "Qadis and Muftis - CornellCast". CornellCast. Retrieved 2017-09-12.

- LookLex.

- Tillier, Mathieu (2009-12-05), "I - Les districts et leur étendue", Les cadis d'Iraq et l'État Abbasside (132/750-334/945), Études arabes, médiévales et modernes, Beyrouth: Presses de l’Ifpo, pp. 280–329, ISBN 978-2-35159-278-6

- Tillier, Mathieu (2009-12-05), "I - La constitution d'un réseau épistolaire", Les cadis d'Iraq et l'État Abbasside (132/750-334/945), Études arabes, médiévales et modernes, Beyrouth: Presses de l’Ifpo, pp. 366–399, ISBN 978-2-35159-278-6

- Tillier, Mathieu (2009-12-05), "II - Passation de pouvoir et continuité judiciaire", Les cadis d'Iraq et l'État Abbasside (132/750-334/945), Études arabes, médiévales et modernes, Damascus: Presses de l’Ifpo, pp. 399–422, ISBN 978-2-35159-278-6

- Tillier, Mathieu, "Chapitre 5. La justice des non-musulmans dans le Proche-Orient islamique", L'invention du cadi : La justice des musulmans, des juifs et des chrétiens aux premiers siècles de l'Islam, Bibliothèque historique des pays d’Islam, Paris: Éditions de la Sorbonne, pp. 455–533, ISBN 979-10-351-0102-2

- Tillier, Mathieu (2018-11-01), Emon, Anver M.; Ahmed, Rumee (eds.), "The Mazalim in Historiography", The Oxford Handbook of Islamic Law, Oxford University Press, pp. 356–380, doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199679010.013.10, ISBN 978-0-19-967901-0

- Morris S. Goodblatt, Jewish Life in Turkey in the XVIth Century as Reflected in the Legal Writings of Samuel de Medina, p. 122.

- Lauren Benton, Law and Colonial Cultures: Legal Regimes in World History, 1400-1900, p. 113.

- Oguamanam, Chidi; Pue, Wesley (October 2, 2006). "Lawyers' Professionalism, Colonialism, State Formation and National Life in Nigeria, 1900-1960: 'The Fighting Brigade of the People'". Retrieved 5 April 2020. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Sonneveld, Nadia; Lindbekk, Monika (30 Mar 2017). Women judges in the Muslim world : a comparative study of discourse and practice. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-34220-0. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- Albisetti, James (July 1, 2000). "Portia Ante Portas: Women and the Legal Profession in Europe, ca. 1870–1925". Journal of Social History. 33 (4): 825–857. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- Cashman, Greer Fay (10 February 2016). "Rivlin and Shaked urge appointment of female Qadis in Shariah Courts". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- Taylor, Pamela (August 7, 2010). "Malaysia appoints first female sharia judges". Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 4, 2013. Retrieved September 13, 2011.

- "Israel appoints country's first female Sharia judge Hana Khatib". Al Arabiya. 2017-04-25.

- EL Hajjami, 2009, 33-34)

- Worldstatesmen: Mayotte.

- Lady Lugard 1997, pp. 199-200.

- Dalgleish 2005.

- O'Callaghan 1975, pp. 142-143.

- O'Callaghan 1975, pp. 269-271.

- Imamuddin 1981, pp. 198-200.

- Peters, Rudolf. "Islamic and Secular Criminal Law in Nineteenth Century Egypt: The Role and Function of the Qadi". Islamic Law and Society 4, no. 1 (1997):77-78.

- Peters, Rudolf. "Islamic and Secular Criminal Law in Nineteenth Century Egypt: The Role and Function of the Qadi". Islamic Law and Society 4, no. 1 (1997):77.

- Malcolm 1994.

- Benton, Lauren A.; Law and Colonial Cultures: Legal Regimes in World History, 1400-1900, p. 114

Sources

- Bekir Kemal Ataman, "Ottoman Kadi Registers as a Source of Social History". Unpublished M.A. Thesis. University of London, University College London, School of Library, Archive and Information Studies. 1987.

- Dalgleish, David (April 2005). "Pre-Colonial Criminal Justice In West Africa: Eurocentric Thought Versus Africentric Evidence" (PDF). African Journal of Criminology and Justice Studies. 1 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2011-06-26.

- Imamuddin, S. M. (1981). Muslim Spain 711-1492 A.D.: a sociological study. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-06131-2.

- Lady Lugard, Flora Louisa Shaw (1997). "Songhay Under Askia the Great". A tropical dependency: an outline of the ancient history of the western Sudan with an account of the modern settlement of northern Nigeria / [Flora S. Lugard]. Black Classic Press. ISBN 0-933121-92-X.

- "Qadi". LookLex Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2011-05-24. Retrieved 2011-06-26.

- Malcolm, Noel (1994). Bosnia: A Short History. Macmillan. p. 50. ISBN 0-330-41244-2.

- O'Callaghan, Joseph F. (1975). A History of Medieval Spain. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-0880-6.

- Özhan Öztürk (2005). Karadeniz (Black Sea): Ansiklopedik Sözlük. 2 Cilt. Heyamola Yayıncılık. İstanbul. ISBN 975-6121-00-9

- "Mayotte". WorldStatesmen. Retrieved 2011-06-26.

- Qureshi, Dr. Ishtiaq Husain (1942). The Administration of the Sultanate of Delhi. Pakistan Historical Society. p. 313.

Further reading

- Schacht, Joseph. An Introduction to Islamic Law. Oxford, 1964.

- Tillier, Mathieu. Les cadis d'Iraq et l'Etat abbasside (132/750-334/945). Damascus, 2009. ISBN 978-2-35159-028-7 Read online: https://web.archive.org/web/20130202072807/http://ifpo.revues.org/673

- Tillier, Mathieu. L’invention du cadi. La justice des musulmans, des juifs et des chrétiens aux premiers siècles de l’Islam. Paris, 2017. ISBN 979-1035100001

- Al-Kindî. Histoire des cadis égyptiens (Akhbâr qudât Misr). Introduction, translation and notes by Mathieu Tillier. Cairo, 2012. ISBN 978-2-7247-0612-3

- Tillier, Mathieu. Vies des cadis de Misr (257/851-366/976). Extrait du Raf' al-isr 'an qudât Misr d'Ibn Hagar al-'Asqalânî. Cairo, 2002. ISBN 2-7247-0327-8

- Tyan, Emile. "Judicial Organization". In Law in the Middle East, vol. 1, edited by Majid Khadduri and Herbert J. Liebesny, pp. 236–278. Washington, D. C., 1955.

- Tyan, Emile. Histoire de l'organisation judiciaire en pays d'Islam. 2d ed. Leiden, 1960.

- "* Qazi courts to be established in Sri Lanka". Colombo Page. Sep 10, 2010. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

External links

| Look up قاض in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |