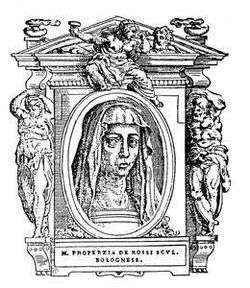

Properzia de' Rossi

Properzia de' Rossi (c. 1490–1530), was an Italian Renaissance sculptor. She studied under the Bolognese artist and master engraver Marcantonio Raimondi, who is best known today for his engravings after paintings by Raphael.

.jpg)

Biography

Properzia de' Rossi was born in Bologna daughter of a notary named Giovanni Martino Rossi da Modena.[1] As a woman of the Renaissance, she studied painting, music, dance, poetry, and classical literature, and studied drawing under Marcantonio Raimondi.[2] Undecided in her youth as to which outlet of self-expression she wanted to pursue, she found her direction when she tried her hand at sculpture, creating small but intricately detailed works of art on apricot, peach, and cherry stones.[3] The subject of these small "friezes" was often religious, with one of the most famous being a Crucifixion in a peach pit. Although the exact date of her transition from painting to sculpture is unknown, it is evident that it happened by the 1520s when records document her entrance in the competition to decorate the high altar of the sanctuary of the Madonna del Baraccano in Bologna.[4] Sculpting aside, de Rossi was noted for her beauty, intellect, and musical talents. Because she was not born into a family of artists, as were most of her female contemporaries, de Rossi had additional barriers to cross in order to pursue a sculpting career, especially in marble. Nonetheless, she received training at the University of Bologna, and with master engraver Marc Antonio Raimondi.[5]

Major commissions

As she approached her thirties, de' Rossi began working in large scale. Her marble portrait busts from this period brought her to prominence. She won a competition to create sculpture for the west facade of San Petronio in Bologna. Records show that she was paid to create three sibyls, two angels, and a pair of bas-relief panels, including a panel depicting Joseph and Potiphar's Wife now in the Museum of San Petronio in Bologna. In the scene, Joseph attempts to escape from the wife of an Egyptian officer. The skillfully executed musculature in combination with classical dress reveal de Rossi's knowledge of antiquity. Additionally, the subject matter of Joseph fleeing from his temptress was a prominent subject matter in the early days of the Counter-Reformation, conveying the dangers of immorality associated with female nature.[6] Giorgio Vasari wrote in his "Life of Madonna Properzia de’ Rossi" that de' Rossi was paid "a most beggarly price for her work." He attributed this to the painter Amico Aspertini working to ruin her commissions and pay.[7] The quality of her later marble busts, including a bust of Count Alessandro de Pepoli, earned her the commission for the decorative program on the high altar of Santa Maria del Baraccano in Bologna in 1524. Although pitted against male competitors, de Rossi was the winner of a commission for the west façade of San Petronio, also in Bologna. Part of the commission included a marble panel depicting the Biblical story of Joseph and Potiphar's Wife, often referred to as her most celebrated piece. Here, she shows adeptness for arranging heroic figures in a broad and dynamic style characteristic of Italian Renaissance relief sculpture. Vasari praised this work but also assumed it depicted de Rossi's personal woes of unrequited love.[8]

Legal issues

De' Rossi's life has been described as tumultuous, having been accused of vandalism of a private garden in 1520, and again with assault of another artist, Amico Aspertini in 1525. In addition, little is known of her life and artistic output after her San Petronio commission. There is, however, documentation of her debt owed to the hospital for victims of the plague in 1529, which not only explains her lack of artistic output but also the bankruptcy she experiences later in life.[9]

Later years

Originally praised for her skill at carving fruit stones, she went on to sculpt portrait busts and, eventually, to beat her male rivals for church commissions. However, tormented by unrequited love for a nobleman, she apparently sickened and died penniless.[10] While de' Rossi won important commissions in her life, she died before reaching forty, bankrupt and without close relatives or friends. The day of her death has been marked unmistakably in records due to the public spectacle that took place on the same day. She died on the same day as Charles V's coronation by Clement VII, 24 February 1530.[1] Clement VII was told that de' Rossi was a "noble and elevated genius", and was informed of her death as he was on his way to meet her.[11]

De' Rossi in The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects

De' Rossi was one of about 40 woman artists, mostly painters, in Renaissance Italy.[12] Female sculptors were rare, for sculpting was considered masculine due to the strength and stamina the medium required of the artists. She was one of four women included in Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Artists, collecting biographies of those he viewed as the most prominent artists of the recent centuries. However, his comments about de' Rossi make his view clear: sculpting is not an art form that women should attempt.[13] For example, while he calls her fruit pit sculptures "miraculous," he also asserts that de' Rossi's depiction of the Egyptian officer's wife was a self-portrait. He claimed that de' Rossi had an unrequited affection for Anton Galeazzo Malvasia, a young nobleman, and the bas-relief panel allowed her to illustrate Malvasia's denial of a romantic relationship. Vasari's assertion was probably founded on an apocryphal story; however, his inclusion of the incident in his biography of Properzia is probably due to a belief in the Renaissance that women were prone to be overcome and hindered by melancholia. Vasari used Properzia's San Petronio as an example of how all women, even those who are great artisans, cannot escape their "female" nature.

Notes

- Roberts Ragg, Laura Maria (1907). The Women Artists of Bologna. London: Methuen. p. 168. hdl:2027/uc1.32106007700112.

- Heller, Nancy G. (1997). Women artists: an illustrated history (3rd ed.). New York: Abbeville Press. p. 23. ISBN 0-7892-0345-6.

- Roberts Ragg, Laura Maria (1907). The Women Artists of Bologna. London: Methuen. pp. 170–171. hdl:2027/uc1.32106007700112.

- Roberts Ragg, Laura Maria (1907). The Women Artists of Bologna. London: Methuen. p. 172. hdl:2027/uc1.32106007700112.

- "Properzia de Rossi." CLARA Database of Women Artists. National Museum of Women in the Arts, 2008. Web. 13 Feb. 2017.

- Chadwick, Whitney (1990). Women, Art, and Society (4th ed.). London: Thames and Hudson. p. 93.

- Vasari, Giorgio (1550). Life of Madonna Properzia de' Rossi. Florence: Torrentino.

- "Properzia de Rossi." CLARA Database of Women Artists. National Museum of Women in the Arts, 2008. Web. 13 Feb. 2017.

- Quin, Sally (April 2012). "Describing the Female Sculptor in Early Modern Italy: An Analysis of the vita of Properzia de' Rossi in Giorgio Vasari's Lives". Gender & History. 24 (1): 134–149. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0424.2011.01672.x.

- {{Campbell-Johnston, Rachel. The women artists painted over by history: We all know about the great masters, but what happened to the great mistresses? Rachel Campbell-Johnston tells the stories of ten inspirational lives [Eire Region]. London (UK): News International Trading Limited, 2014. Print.}}

- Bluestone, Natalie Harris (1995). Double Vision: Perspectives on Gender and the Visual Arts. Toronto: Farleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 43.

- Note: Bernardo de' Dominici, in his 1742 biography (Vite; page 327) of Neapolitan artists, while describing the life of Mariangiola Criscuolo lists a number of then "modern" female artists including: Properzia de Rossi, Lavinia Fontana, and Irene di Spilimbergo, disciple of Titian, la Varotari, la Tintoretta, la Garzoni, and others.

- Quinn, Sally (April 2012). "Describing the Female Sculptor in Early Modern Italy: An Analysis of the vita of Properzia de' Rossi in Giorgio Vasari's Lives". Gender & History. 24 (1): 135.

References

- Chadwick, Whitney, Women, Art, and Society, Thames and Hudson, London, 1990

- Heller, Nancy G. Women Artists: An Illustrated History.New York: Abbeville Press, 1997.

- Harris, Anne Sutherland and Linda Nochlin, Women Artists: 1550-1950, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Knopf, New York, 1976

- Jacobs, Frederika. The Construction of a Life: Madonna Properzia De' Rossi 'Scultrice Bolognese', Word and Image, 1993, pp. 122 – 32.

- Vasari, Giorgio. The Life of Madonna Properzia de' Rossi, in The Lives of the Artists (1568), trans. J. and P. Bondanella, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991, pp. 339 – 44.

- Original text from 1568 edition with illustration of Properzia de' Rossi by Giorgio Vasari on Italian Wikisource

- Griselda Pollock, et al. "Women and art history." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press 2003