Prittlewell royal Anglo-Saxon burial

The Prittlewell royal Anglo-Saxon burial or Prittlewell princely burial is a high-status Anglo-Saxon burial mound which was excavated at Prittlewell, north of Southend-on-Sea, in the English county of Essex.

Map of Essex showing the location of Prittlewell | |

| Location | Essex, England |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 51.55391°N 0.70873°E |

| Type | Anglo-Saxon burial mound |

| History | |

| Founded | c. 580 |

| Periods | Anglo-Saxon England |

| Cultures | Anglo-Saxons |

| Associated with | ?Sæxa, brother of Sæberht of Essex |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 2003 |

| Archaeologists | MOLA |

| Ownership | Southend Borough Council |

| Website | prittlewellprincelyburial |

Artefacts found by archaeologists in the burial chamber are of a quality that initially suggested that this tomb in Prittlewell was a tomb of one of the Anglo-Saxon Kings of Essex, and the discovery of golden foil crosses indicate that the burial was of an early Anglo-Saxon Christian. The burial is now dated to about 580 AD, and is thought that it contained the remains of Sæxa, brother of Sæberht of Essex.

In May 2019, some of the excavated artefacts went on permanent display in Southend Central Museum.[1][2]

Excavation

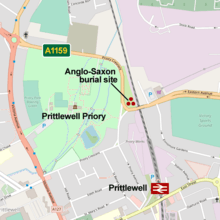

In the autumn of 2003, in preparation for a road-widening scheme, an archaeological survey was carried out on a plot of land to the north-east of Priory Park in Prittlewell. Earlier excavations had indicated Anglo-Saxon burials in the area, however it was not expected that such a significant find could be made. The archaeologists were lucky in the placement of their trench and uncovered a large Anglo-Saxon burial, and removed many important artefacts, mostly in metalwork.[3] The site is located between the A1159 road and the Shenfield–Southend railway line, close to an Aldi supermarket and The Saxon King pub.

Archaeologists from the Museum of London Archaeology Service, under the supervision of Atkins Ltd, excavated the site and discovered an undisturbed 7th-century chamber grave beneath a mound. They described it as "the most spectacular discovery of its kind made during the past 60 years".

In total, about 110 objects were lifted by conservators in two phases, over a period of ten days. Some of the objects were block-lifted together with the soil that they were embedded in. The final lift was completed on 20 December 2003, with final defining of the chamber walls and back-filling continuing for three days after.[4]

The quality and preservation of the Prittlewell chamber burial has led to comparisons with the Sutton Hoo Ship Burial and associated graves, discovered in 1939, as well as with the discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb in 1922.[5][6]

Burial chamber and artefacts

Excavation demonstrated the burial chamber to be a deep, formerly timber-walled room full of objects of copper, gold, silver and iron, which had gradually collapsed and filled with soil as its wooden containing walls and ceiling decayed. The finds included an Anglo-Saxon hanging bowl, decorated with inlaid escutcheons and a cruciform arrangement of applied strips, a folding stool, three stave-built tubs or buckets with iron bands, a sword and a lyre, the last one of the most complete found in Britain.[4] The tomb itself is 4 metres (13 ft) square, the largest chambered tomb ever discovered in England.[7]

The body had been laid in a wooden coffin, with two small gold-foil crosses, one over each eye. One opinion was that he had been laid in the coffin by Christians, and that the coffin had been then buried by pagans. The acidic sandy soil had completely dissolved the body's bones, and any other bone in the tomb, but some pieces of human teeth were found, but too far affected by decay for DNA to be found in them.

The inventory of grave goods is comparable to one found in a burial in the Taplow Barrow in 1883, and though the overall collection is less sumptuous than that from the ship-burial in Mound 1 at Sutton Hoo, many individual objects are closely comparable and of similar quality. For example, there is a hollow gold belt buckle, but much plainer than that from Sutton Hoo, but the lyre, drinking vessels, and copper-alloy shoe buckles are very similar.[4] As at Sutton Hoo, the best hope for closely dating the burial is the Merovingian gold coins, however the dating of these is a complicated matter, based on their metallic content rather than the design and information stamped on them. Research continues on this as on other aspects of the find, but the evidence initially suggests a date in the period 600–650,[4] or 600–630.[8] There is an object identified as a "standard", as at Sutton Hoo, but of a different type, and there is a folding stool of a type often seen in royal portraits in Early Medieval manuscripts (like a "curule seat") that is a unique find in England, and was probably imported.[4][5]

The design of the lyre was reconstructed from soil impressions and surviving metal pieces. There was evidence that it had been repaired at least once. A copy of it was made in yew wood and played to accompany a funeral song sung for King Sæberht in Old English and English in St Mary's Church in Southend.[9]

Theories about occupant

The quality of the locally made objects, and the presence of imported luxury items such as the Coptic bowl and flagon, appear to point to a royal burial. The most obvious candidates were originally thought to be either Sæberht of Essex (died 616 AD) or his grandson Sigeberht II of Essex (murdered 653 AD), who are the two East Saxon Kings known to have converted to Christianity during this period. As the evidence pointed to an early seventh century date, Sæberht was considered more likely.[9]

However, carbon-dating techniques have since indicated a revised date in the late 6th century. In May 2019, it was reported that a team of 40 specialists from the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) now believe the tomb could have belonged to Saexa, Sæberht's brother. Carbon dating had indicated that the tomb was built between 575 and 605, at least 11 years before Sæberht's death.[1][10][2] Further details of the latest research have been published on the MOLA website.[11]

It is, however, also possible that the occupant is of some other wealthy and powerful individual whose identity has gone unrecorded.[4] In the meantime, the occupant has acquired the popular nickname of the "King of Bling", in reference to the rich grave goods.[12]

For many years the location of Sæberht's remains has been uncertain. Medieval legend claims that Sæberht and his wife Queen Ethelgoda founded a monastery in London in 604 that later became the site of Westminster Abbey, and that they had been buried in the church there. A recessed marble tomb in the south ambulatory of the abbey purportedly contains the bones of Sæberht, although modern scholars cast doubt on its veracity.[13][14]

Post-excavation events

In 2004 a re-dedication of the King's tomb was hosted by the Bishop of Chelmsford John Gladwin and a large celebration event took place attended by over 5000 people in the area. The tomb was de-dedicated in a ceremony held at Prittlewell Priory supported by 85 local churches and voluntary organisations entitled 'Discover the King'. The event patron was local MP Sir Teddy Taylor and the chair of the organising event was Jonathan Ullmer.

After the discovery of the Prittlewell tomb and the completion of archaeological excavations, local protestors campaigned for Southend Borough Council to cancel the A1159 road road widening scheme, as the planned road would go across the burial site. From September 2005 to July 2009 the site was occupied by a road protest camp known locally as Camp Bling.[12] In 2009 Southend Borough Council announced an alternative road improvement scheme at nearby Cuckoo Corner.[15]

The Prittlewell tomb featured in a 2005 special episode of Channel 4's archaeological series Time Team, entitled "King of Bling", and devoted to Prittlewell.[9]

The archaeological work was the winner of the Developer Funded Archaeology Award as part of the British Archaeological Awards for 2006.[16] Southend Borough Council undertook to find a home for the archaeological finds in order to keep them in the borough, and announced that a new gallery would be created at Southend Central Museum to display the artefacts.[4] After restoration work and carbon dating had been completed, the new museum gallery opened to the public in May 2019.[17]

Early Anglo-Saxon Prittlewell

In addition to the princely burial, there is other archaeological evidence of early Anglo-Saxon occupation of Prittlewell. A 1923 excavation in Priory Crescent revealed a 6th or 7th century Anglo-Saxon cemetery which may have extended into what is now Priory Park. The parish church, a short distance to the south, contains a remnant of a 7th-century church.[18]

Notes

- "Southend burial site 'UK's answer to Tutankhamun'". BBC. 9 May 2019. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- Brown, Mark (8 May 2019). "Britain's equivalent to Tutankhamun found in Southend-on-Sea". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 May 2019. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- "Prittlewell prince:- Britain's answer to Tutankhamun". Stuff (Fairfax). 10 May 2019.

- Blair, Barham & Blackmore 2004.

- MoLAS 2004.

- Jackson, Sophie (14 May 2019). "Tut Tut? Why compare Prittlewell's princely burial to King Tutankhamun's tomb?". MOLA. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- Pollington, Stephen (2008). Anglo-Saxon Burial Mounds. Anglo-Saxon Books. p. 21.

- Southend Museums 2004.

- "Prittlewell, Southend: The 'King of Bling'". Time Team. Time Team (specials). 13 June 2005. Channel 4. Archived from the original on 10 December 2006. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- Smith, Roth (9 May 2019). "New research questions famed burial of 'first' Christian Anglo-Saxon king". National Geographic. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- "Prittlewell Princely Burial". MOLA. Archived from the original on 9 May 2019. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- "The battle for the 'King of Bling'". BBC News. 6 February 2006. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- Jenkyns, Richard (2011). "The Medieval Church". Westminster Abbey. Harvard University Press. p. 10. ISBN 9780674061972. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- "Sebert, King of the East Saxons & Ethelgoda". Westminster Abbey. Archived from the original on 15 May 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- "Cuckoo Corner Improvement Scheme – Proposal" (PDF). Southend-On-Sea Borough Council. 2009-09-29. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-07-14. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- "BRITISH ARCHAEOLOGICAL AWARDS 2006". Council for British Archaeology. Retrieved 2009-04-30.

- Whitehouse, Ellis. "Anglo-Saxon king exhibition showing 'Southend's rich cultural heritage' officially opens". Halstead Gazette. Archived from the original on 13 May 2019. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- Hirst, Sue (2004). The Prittlewell Prince. Museum of London Archaeology Service.

References

- Blair, Ian; Barham, Liz; Blackmore, Lyn (May 2004). "My Lord Essex". British Archaeology (76): 10–17. Archived from the original on 24 April 2005. Retrieved 11 May 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- MoLAS (2004). "Report: The Prittlewell Prince". Museum of London. MoLAS. Archived from the original on 19 January 2009. Retrieved 9 May 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Southend Museums (2004). "Treasures of a Saxon King of Essex". Southend Museums. Archived from the original on 1 May 2004. Retrieved 9 May 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hirst, Sue; Scull, Christopher (2019). The Anglo-Saxon princely burial at Prittlewell, Southend-on-Sea. MoLA. ISBN 978-1-907586-47-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lyn, Blackmore; Blair, Ian; Hirst, Sue; Scull, Christopher (2019). The Prittlewell princely burial: excavations at Priory Crescent, Southend-on-Sea, Essex, 2003. MoLA. ISBN 978-1-907586-50-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- "Britain's oldest Christian royal burial site 'is the Anglo-Saxon world's Tutankhamun'". Australian Broadcasting Corporation News. 10 May 2019.

- Whybra, Julia (Autumn 2014). "The Identity of the Prittlewell Prince". Essex Journal. Chichester, UK: Phillimore. ISSN 0014-0961.

External links

- "#PrittlewellPrince – photos of the excavation and artefacts from the Prittlewell tomb". Flickr. Southend-on-Sea Borough Council/MoLA. 12 September 2012. Archived from the original on 14 May 2019. Retrieved 14 May 2019.