Hanging bowl

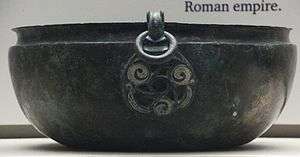

Hanging bowls are a distinctive type of artifact of the period between the end of Roman rule in Britain in c. 410 AD and the emergence of the Christian Anglo-Saxon kingdoms during the 7th century. The surviving examples have mostly been found in Anglo-Saxon graves, but there is general agreement that they reflect Celtic traditions of decoration.

The bowls are usually of thin beaten bronze, between 15–30 cm (6-12 inches) in diameter, and dished or cauldron-shaped in profile. Typically they have three decorative plates ('escutcheons') applied externally just below the rim to support hooks with rings, by which they were suspended. The ornament of these plates is often very sophisticated, and in many cases includes beautiful coloured enamel work, commonly in champlevé and using spiral motifs. Although their designs and manufacture are thought to proceed from Celtic technique, they are principally found in eastern Britain, and especially in the areas which received Anglo-Saxon acculturation. Their production is also evidenced in Pictish and Irish contexts, but they seem almost completely absent from Wales, Devon and Cornwall.

Rupert Bruce-Mitford's corpus gives the following breakdown of the locations in modern terms of the 174 finds he includes (many are just one or more elements of a bowl):[1]

- England 117, Scotland 7, Ireland 17

- Norway 26, Sweden 2, Denmark 1,

- Germany 2, Belgium 1, Netherlands 1

Function

The bowls are enigmatic because their intended function is not certainly known. Many have finely-worked escutcheons set centrally within, which makes it unlikely that they could have contained opaque or sticky material such as lamp-fat. The theory that they were used as maritime compasses, with a magnetic pin floated on water within the bowl, is discounted because many have an iron band around the rim which would render this unworkable. Another opinion is that they were used for the Roman custom of mixing wine and water for service at table. Some bowls are too small to make this explanation workable if general potation were intended. However, in ritual Christian or other meals it would be possible for a group to dip bread into such a wine-bowl in imitation of the Last Supper.

Part of the puzzle lies in whether the bowls were normally suspended by threads from a central fulcrum (like a lamp), or from hooks on a tripod with tall wooden legs. There is some support for the latter view, because the nearest formal parallel for such bowls from Antique contexts is in depictions of the Oracular Cortina, a three-hooked bowl suspended within a tripod, over which the priestess sat when pronouncing oracles. Certainly if water were contained in the bowls it is more likely to have been for ritual or liturgical purposes than for general consumption owing to the limited capacity. This would therefore be 'special' water, perhaps consecrated for baptism or aspersion, or (in other religious circumstances) derived from a sacred source or spring. 'Tripods' are also mentioned as prizes for warriors in early literature, including the early Welsh.

Motifs

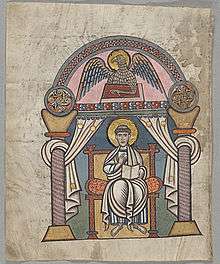

Some bowls have clearly Christian motifs on their escutcheons. The spiral ornament developed through the 6th to 7th century invention of the 'trumpet-spiral' pattern, which was afterwards adopted from these enamels and incorporated into the repertoire of the famous painted Gospel-books such as the Book of Durrow or the Lindisfarne Gospels. This painted decoration was certainly intended for meditative contemplation and as a devotional work. From the very mixed cultures and beliefs of the inhabitants of Britain during the Dark Ages, the art, and perhaps some part of the function of these bowls became absorbed into the Celto-Saxon ornamental language of Christian Britain. Among the finest examples is the large bowl from the Sutton Hoo ship-burial (near Woodbridge, Suffolk), which has an enameled fish sculpture set to swivel on a pin within the bowl.[2]

Influence on church plate

The distinctive shape of the two most famous early Irish chalices, the Ardagh Chalice and the Derrynaflan Chalice has been described as an adaptation of the hanging bowl form for a different use,[3] although others see them as using shapes derived from Byzantine metalwork.

See also

Sources

The hanging bowls have been discussed in detail by many scholars, among them John Romilly Allen, Françoise Henry, Sir Thomas Kendrick, Rupert Bruce-Mitford, Hayo Vierck, Jane Brenan, and most recently in the authoritative study begun by Bruce-Mitford and completed by Sheila Raven (citation below).

- R.L.S. Bruce-Mitford, The Sutton Hoo Ship-Burial Volume III Part I, 1983 (British Museum)

- R.L.S. Bruce-Mitford and Sheila Raven, A Corpus of Late Celtic Hanging Bowls with an account of the bowls found in Scandinavia, 2005 (OUP)

- Susan Youngs, 'The Work of Angels', Masterpieces of Celtic Metalwork, 6th-9th Centuries AD, 1989 (British Museum)

- G.D.S. Henderson, Vision and Image in Early Christian England, 1999 (CUP) - Chapter 1.

Notes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hanging bowls. |

- Table 2, p. 64

- British Museum Hanging bowl from the ship-burial at Sutton Hoo.

- Ryan, Patrick. in Youngs, 131