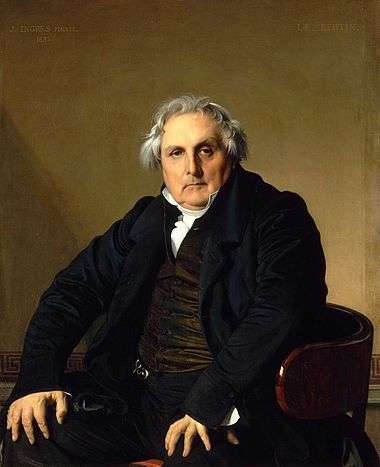

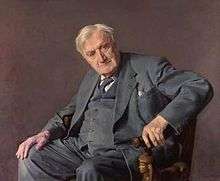

Portrait of Monsieur Bertin

Portrait of Monsieur Bertin is an 1832 oil on canvas painting by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. It depicts Louis-François Bertin (1766–1841), the French writer, art collector and director of the pro-royalist Journal des débats. Ingres completed the portrait during his first period of success; having achieved acclaim as a history painter, he accepted portrait commissions with reluctance, regarding them as a distraction from more important work. Bertin was a friend and a politically active member of the French upper-middle class. Ingres presents him as a personification of the commercially minded leaders of the liberal reign of Louis Philippe I. He is physically imposing and self-assured, but his real-life personality shines through – warm, wry and engaging to those who had earned his trust.

The painting had a prolonged genesis. Ingres agonised over the pose and made several preparatory sketches. The final work faithfully captures the sitter's character,[1] conveying both a restless energy and imposing bulk. It is an unflinchingly realistic depiction of ageing and emphasises the furrowed skin and thinning hair of an overweight man who yet maintains his resolve and determination. He sits in three-quarter profile against a brown ground lit from the right, his fingers are pronounced and highly detailed, while the polish of his chair reflects light from an unseen window.

Ingres' portrait of Bertin was a critical and popular success, but the sitter was a private person. Although his family worried about caricature and disapproved, it became widely known and sealed the artist's reputation. It was praised at the Paris Salon of 1833, and has been influential to both academic painters such as Léon Bonnat and later modernists including Pablo Picasso and Félix Vallotton. Today art critics regard it as Ingres' finest male portrait. It has been on permanent display at the Musée du Louvre since 1897.

Background

Louis-François Bertin was 66 in 1832, the year of the portrait.[1] He befriended Ingres either through his son Édouard Bertin, a student of the painter,[2] or via Étienne-Jean Delécluze, Ingres' friend and the Journal's art critic.[3] In either case the genesis of the commission is unknown. Bertin was a leader of the French upper class and a supporter of Louis Philippe and the Bourbon Restoration. He was a director of the Le Moniteur Universel until 1823, when the Journal des débats became the recognised voice of the liberal-constitutional opposition after he had come to criticize absolutism. He eventually gave his support to the July Monarchy. The Journal supported contemporary art, and Bertin was a patron, collector and cultivator of writers, painters and other artists.[4] Ingres was sufficiently intrigued by Bertin's personality to accept the commission.[2]

It was completed within a month, during Ingres' frequent visits to Bertin's estate of retreat, Le Château des Roches, in Bièvres, Essonne. Ingres made daily visits, as Bertin entertained guests such as Victor Hugo, his mistress Juliette Drouet, Hector Berlioz, and later Franz Liszt and Charles Gounod.[5] Ingres later made drawings of the Bertin family, including a depiction of his host's wife and sketches of their son Armand and daughter-in-law, Cécile. The portrait of Armand evidences his physical resemblance to his father.[6]

Ingres' early career coincided with the Romantic movement, which reacted against the prevailing neoclassical style. Neoclassicism in French art had developed as artists saw themselves as part of the cultural center of Europe, and France as the successor to Rome.[7] Romantic painting was freer and more expressive, preoccupied more with colour than with line or form, and more focused on style than on subject matter. Paintings based on classical themes fell out of fashion, replaced by contemporary rather than historical subject matter, especially in portraiture. Ingres resisted this trend,[8] and wrote, "The history painter shows the species in general; while the portrait painter represents only the specific individual—a model often ordinary and full of shortcomings."[9] From his early career, Ingres' main source of income was commissioned portraits, a genre he dismissed as lacking in grandeur. The success of his The Vow of Louis XIII at the 1824 Salon marked an abrupt change in his fortunes: he received a series of commissions for large history paintings, and for the next decade he painted few portraits.[10] His financial difficulties behind him, Ingres could afford to concentrate on historical subjects, although he was highly sought-after as a portraitist. He wrote in 1847, "Damned portraits, they are so difficult to do that they prevent me getting on with greater things that I could do more quickly."[11]

Ingres was more successful with female than male portraits. His 1814 Portrait of Madame de Senonnes was described as "to the feminine what the Louvre's Bertin is to the masculine". The sitter for his 1848 Portrait of Baronne de Rothschild looks out at the viewer with the same directness as Bertin, but is softened by her attractive dress and relaxed pose; she is engaging and sympathetic rather than tough and imposing.[11]

The portrait

Preparation and execution

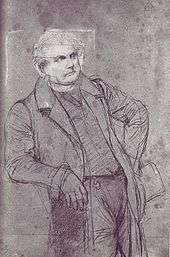

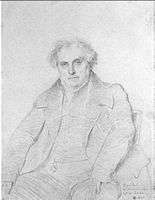

Ingres was self-critical and consumed by self-doubt. He often took months to complete a portrait,[12] leaving large periods of inactivity between sittings. With Bertin, he agonised in finding a pose to best convey both the man's restless energy and his age. At least seven studies survive,[13] three are signed and dated. Ingres was a master draftsman and the sketches, if not fully realised, are highly regarded in their own right. The sketches are exemplary in their handling of line and form, and similar in size.[14]

The earliest study has Bertin standing and leaning on a table in an almost Napoleonic pose.[15] His hard, level stare is already established, but the focus seems to be on his groin rather than his face.[16] Ingres struggled with the sketch; the head is on a square of attached paper which must have replaced an earlier cut-out version, and other areas have been rubbed over and heavily reworked. The next extant drawing shows Bertin seated, but the chair is missing. The last extant sketch is the closest to the eventual painting, with a chair, though his bulk has not yet been filled out.[4]

Frustrated by his inability to capture his subject, Ingres broke down in tears in his studio, in company. Bertin recalled "consoling him: 'my dear Ingres, don't bother about me; and above all don't torment yourself like that. You want to start my portrait over again? Take your own time for it. You will never tire me, and just as long as you want me to come, I am at your orders.'"[17] After agreeing to a breathing spell Ingres finally settled on a design.

Early biographers provide differing anecdotes regarding the inspiration for the distinctive seated pose. Henri Delaborde said Ingres observed Bertin in this posture while arguing politics after dinner with his sons.[18] According to Eugène Emmanuel Amaury Duval (who said he had heard the story from Bertin), Ingres noticed a pose Bertin took while seated outside with Ingres and a third man at a café.[19] Bertin said that Ingres, confident that he had finally established the pose for the portrait, "came close and speaking almost in my ear said: 'Come sit tomorrow, your portrait is [as good as] done.'"[20][21] Bertin's final pose reverses the usual relationship between the two men. The artist becomes the cool, detached observer; Bertin, usually calm and reasoned, is now restless and impatient, mirroring Ingres' irritation at spending time on portraiture.[22]

Ingres, Study for the Portrait of Monsieur Bertin, 1832. Musée du Louvre, Paris

Ingres, Study for the Portrait of Monsieur Bertin, 1832. Musée du Louvre, Paris Ingres, Study for the Portrait of Monsieur Bertin, 1832. Bequeathed to the Louvre by Grace Rainey Rogers in 1943

Ingres, Study for the Portrait of Monsieur Bertin, 1832. Bequeathed to the Louvre by Grace Rainey Rogers in 1943 Ingres, study of Bertin's right hand. Graphite on tracing paper. Fogg Museum, Harvard, MA

Ingres, study of Bertin's right hand. Graphite on tracing paper. Fogg Museum, Harvard, MA

Description

Bertin is presented as strong, energetic and warm-hearted.[4] His hair is grey verging on white, his fingers spread across his knees. Bertin's fingers were described in 1959 by artist Henry de Waroquier as "crab-like claws ... emerging from the tenebrous caverns that are the sleeves of his coat."[23] The bulk of his body is compacted in a tight black jacket, black trousers and brown satin waistcoat, with a starched white shirt and cravat revealing his open neck. He wears a gold watch and a pair of glasses in his right pocket. In the view of art historian Robert Rosenblum, his "nearly ferocious presence" is accentuated by the tightly constrained space. The chair and clothes appear too small to contain him. His coiled, stubby fingers rest on his thighs, barely protruding from the sleeves of his jacket, while his neck cannot be seen above his narrow starched white collar.[24]

The painting is composed in monochrome, muted colours; predominately blacks, greys and browns. The exceptions are the whites of his collar and sleeves, the reds in the cushion[24] and the light reflecting on the leather of the arm-chair.[25] In 19th-century art, vivid colour was associated with femininity and emotion; male portraiture tended towards muted shades and monochrome.[26] Bertin leans slightly forward, boldly staring at the viewer in a manner that is both imposing and paternal. He seems engaged, and poised to speak,[27] his body fully towards the viewer and his expression etched with certainty.[28] Influenced by Nicolas Poussin's 1650 Self-Portrait with Allegory of Painting, Ingres minutely details the veins and wrinkles of his face.[29] Bertin is in three-quarter profile, against a gold–brown background lit from the right. He rests on a curved-back mahogany chair, the arms of which reflect light falling from the upper left of the pictorial space.[13]

Ingres seems to have adapted elements of the approach and technique of Hans Holbein's 1527 Portrait of William Warham, now in the Louvre. Neither artist placed much emphasis on colour, preferring dark or cool tones. The Warham portrait seems to have informed the indicators of Bertin's aging and the emphasis on his fingers.[30] Jacques-Louis David also explored hyper-realism in his depictions of Cooper Penrose (1802) and Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès (1817). In the later painting, David shows tiny glints of light reflecting on the sitter's chair and painstakingly details "every wayward curl of [Sieyès'] closely cropped auburn hair."[31]

The Greek meander pattern at the foot of the wall is unusually close to the picture plane, confining the sitter. The wall is painted in gold, adding to the sense of a monumental portrait of a modern icon.[32] The details of Bertin's face are highly symmetrical. His eyes are heavily lidded, circled by oppositely positioned twists of his white collar, the winds of his hair, eyebrows and eyelids. His mouth turns downwards at the left and upwards to the right.[24] This dual expression is intended to show his duality and complex personality: he is a hard-nosed businessman, and a patron of the arts. The reflection of a window can be seen in the rim of Bertin's chair. It is barely discernible, but adds spatial depth. The Portrait of Pope Leo X (c. 1519) by Raphael, a source for the Bertin portrait, also features a window reflection of the pommel on the pope's chair.[33]

The painting is signed J.Ingres Pinxit 1832 in capitals at the top left, and L.F. Bertin, also in capitals, at the upper right.[34] The frame is the original, and thought to have been designed by Ingres himself. It shows animals around a sinuous and richly carved grapevine. Art historians Paul Mitchell and Lynn Roberts note that the design follows an old French tradition of placing austere male portraits within "exuberantly carved" frames. The frame closely resembles that of Raphael's c. 1514–15 Portrait of Baldassare Castiglione, a painting that influenced Ingres, especially in colour and tone.[35] A similar frame was used for Ingres's 1854 painting of Joan of Arc at the Coronation of Charles VII.[36]

Reception

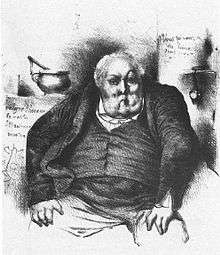

Monsieur Bertin was exhibited at the 1833 Salon alongside his 1807 Portrait of Madame Duvaucey. It met with near universal praise to become his most successful artwork to that point. It sealed his reputation as a portraitist, reaching far enough into public consciousness to become a standard for newspaper political satires. Today it is considered his greatest portrait. Ingres viewed all this as a mixed blessing, remarking that "since my portraits of Bertin and Molé, everybody wants portraits. There are six that I've turned down, or am avoiding, because I can't stand them."[37] Before the official exhibition, Ingres displayed the painting in his studio for friends and pupils. Most were lavish in their praise, although Louis Lacuria confided to a friend that he feared people might "find the colouring a bit dreary".[38] He proved correct; at the Salon, critics praised the draftsmanship, but some felt the portrait exemplified Ingres' weakness as a colourist.[39] It was routinely faulted for its "purplish tone"—which the ageing of the oil medium has transformed over time to warm greys and browns.[40] Bertin's wife Louis-Marie reportedly did not like the painting; his daughter, Louise, thought it transformed her father from a "great lord" to a "fat farmer".[41]

Given the standings of the two men, the painting was received in both social and political terms. A number of writers mentioned Bertin's eventful career, in tones that were, according to art historian Andrew Carrington Shelton, either "bitingly sarcastic [or] fawningly reverential".[38] There were many satirical reproductions and pointed editorials in the following years. Aware of Bertin's support of the July Monarchy, writers at the La Gazette de France viewed the portrait as the epitome of the "opportunism and cynicism" of the new regime. Their anonymous critic excitedly wondered "what bitter irony it expresses, what hardened skepticism, sarcasm and ... pronounced cynicism".[42]

Several critics mentioned Bertin's hands. Twentieth-century art historian Albert Boime described them as "powerful, vulturine ... grasping his thighs in a gesture ... projecting ... enormous strength controlled". Some contemporary critics were not so kind. The photographer and critic Félix Tournachon was harshly critical, and disparaged what he saw as a "fantastical bundle of flesh ... under which, instead of bones and muscles, there can only be intestines – this flatulent hand, the rumbling of which I can hear!"[43] Bertin's hands made a different impression on the critic F. de Lagenevais, who remarked: "A mediocre artist would have modified them, he would have replaced those swollen joints with the cylindrical fingers of the first handy model; but by this single alteration he would have changed the expression of the whole personality ... the energetic and mighty nature".[18]

The work's realism attracted a large amount of commentary when it was first exhibited. Some saw it as an affront to Romanticism, others said that its small details not only showed an acute likeness, but built a psychological profile of the sitter. Art historian Geraldine Pelles sees Bertin as "at once intense, suspicious, and aggressive".[44] She notes that there is a certain amount of projection of the artist's personality and recalls Théophile Silvestre's description of Ingres; "There he was squarely seated in an armchair, motionless as an Egyptian god carved of granite, his hands stretched wide over parallel knees, his torso stiff, his head haughty".[44] Some compared it to Balthasar Denner, a German realist painter influenced by Jan van Eyck. Denner, in the words of Ingres scholar Robert Rosenblum, "specialised in recording every last line on the faces of aged men and women, and even reflections of windows in their eyes."[24] The comparison was made by Ingres' admirers and detractors alike. In 1833, Louis de Maynard of the Collège-lycée Ampère, writing in the influential L'Europe littéraire, dismissed Denner as a weak painter concerned with hyperrealistic "curiosities", and said that both he and Ingres fell short of the "sublime productions of Ingres' self-proclaimed hero, Raphael."[38]

The following year Ingres sought to capitalise on the success of his Bertin portrait. He showed his ambitious history painting The Martyrdom of Saint Symphorian at the 1834 Salon, but it was harshly criticised; even Ingres' admirers offered only faint praise.[45] Offended and frustrated, Ingres declared he would disown the Salon, abandon his residence in Paris for Rome, and relinquish all current positions, ending his role in public life. This petulance was not to last.[46]

Bertin bequeathed the portrait to his daughter Louise (1805–1877) on his death. She passed it to her niece Marie-Louise-Sophie Bertin (1836–1893) wife of Jules Bapst, a later director of the Journal des débats. They bequeathed it to their niece Cécile Bapst, its last private owner. In 1897 Cécile sold it to the Musée du Louvre for 80,000 francs.[40]

Legacy

The Bertin portrait has been hugely influential. At first it served as a model for depictions of energetic and intellectual 19th-century men, and later as a more universal type. Several 1890s works closely echo its form and motifs. Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant's monochrome and severe 1896 Portrait of Alfred Chauchard is heavily indebted,[47] while Léon Bonnat's stern 1892 portrait of the aging Ernest Renan has been described as a "direct citation" of Ingres' portrait.[48]

Its influence can be seen in the dismissive stare and overwhelming physical presence of the sitter in Pablo Picasso's 1906 Portrait of Gertrude Stein.[24] Picasso admired Ingres and referred to him throughout his career. His invoking of Bertin can be read as a humorous reference to, according to Robert Rosenblum, "Stein's ponderous bulk and sexual preference".[47] Stein does not possess Bertin's ironic stare, but is similarly dressed in black, and leans forward in an imposing manner, the painting emphasising her "massive, monumental presence".[49] In 1907 the Swiss artist Félix Vallotton depicted Stein, in response to Picasso, making an even more direct reference to Ingres' portrait,[47] prompting Édouard Vuillard to exclaim, "That's Madame Bertin!"[50]

The influence continued through the 20th century. Gerald Kelly recalled Bertin when painting his restless and confined series of portraits of Ralph Vaughan Williams between 1952 and 1961.[51] In 1975 Marcel Broodthaers produced a series of nine black and white photographs on board based on Ingres' portraits of Bertin and Mademoiselle Caroline Rivière.[52]

References

Notes

- Boime (2004), 325

- Pomarède (2006), 273

- Ingres and Delécluze first met in Jacques-Louis David's studio in 1797. See Rosenblum (1999), 28

- Burroughs (1946), 156

- Shelton (1999), 318

- Shelton (1999), 320

- Zamoyski (2005), 8

- Ingres' critically maligned The Martyrdom of Saint Symphorian has been described as "the perfect illustration of the system's breakdown". See Jover (2005), 180

- Jover (2005), 180–2

- Mongan and Naef (1967), xxi

- Rosenblum (1990), 114

- Jover (2005), 183–4

- Shelton (1999), 303

- Burroughs (1946), 157

- Rifkin (2000), 142

- Jover (2005), 182

- Pach (1939), 74

- Cohn; Siegfried (1980), 102

- Shelton (1999), 302

- Rifkin (2000), 143

- In another version of the story, Ingres saw Amaury Duval take up the pose. See Rosenblum (1990), 102

- Rifkin (2000), 130

- Tinterow; Conisbee (1999), 306

- Rosenblum (1990), 102

- Rifkin (2000), 141

- Garb (2007), 32

- "Louis-François Bertin. Musée du Louvre. Retrieved 17 January 2015

- Jover (2005), 184

- Rosenblum (1990), 31

- Pach (1939), 13

- Rosenblum (1999), 6

- Lubar, Robert. "Unmasking Pablo's Gertrude: Queen Desire and the Subject of Portraiture". The Art Bulletin, volume 79, nr. 1, 1997

- Garb (2007), 154

- Toussaint (1985), 72

- Shelton (1999), 305

- Notes on frames in the exhibition, Portraits by Ingres, National Portrait Gallery, February 1999

- Jover (2005), 216

- Shelton (1999), 304

- Shelton (1999), 503

- Shelton (1999), 306

- Shelton (1999), 303–4

- Shelton (1999), 304–5

- Shelton (2005), 234

- Pelles (1963), 82

- Mongan and Naef (1967), opposite plate 62

- Sterling (1999), 504–5

- Rosenblum (1999), 16

- "Bertin, a newspaper magnate". Musée du Louvre. Retrieved 1 February 2015

- Giroud (2007), 23

- Newman et al. (1991), 118

- "Twelve Twentieth-Century Portraits". National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 6 February 2015

- "Mademoiselle Rivière and Monsieur Bertin 1975". Tate Modern. Retrieved 1 February 2015

Bibliography

- Boime, Albert. Art in an Age of Counterrevolution, 1815–1848. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-226-06337-9

- Burroughs, Louise. "Drawings by Ingres". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, volume 4, no. 6, 1946

- Cohn, Marjorie; Siegfried, Susan. Works by J.-A.-D. Ingres in the collection of the Fogg Art Museum. Cambridge, MA: Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, 1980. OCLC 6762670

- Garb, Tamar. The Painted Face, Portraits of Women in France, 1814–1914. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-300-11118-7

- Giroud, Vincent. Picasso and Gertrude Stein. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2007. ISBN 978-1-58839-210-7

- Jover, Manuel. Ingres. Bologna: Terrail, 2005. ISBN 978-2-87939-289-9

- Mongan, Agnes; Naef, Hans. Ingres Centennial Exhibition 1867–1967: Drawings, Watercolors, and Oil Sketches from American Collections. Greenwich, CT: Distributed by New York Graphic Society, 1967. OCLC 170576

- Newman, Sasha; Vallotton, Félix; Ducrey, Marina; Baier, Lesley. Félix Vallotton. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1991. 118. ISBN 978-1-55859-312-1

- Pach, Walter. Ingres. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1939. ASIN B004XFFC1A

- Pelles, Geraldine. Art, Artists and Society: Origins of a Modern Dilemma; Painting in England and France, 1750–1850. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1963

- Pomarède, Vincent (ed). Ingres: 1780–1867. Paris: Gallimard, 2006. ISBN 978-2-07-011843-4

- Rifkin, Adrian. Ingres: Then and Now. New York: Routledge, 2000. ISBN 978-0-415-06697-6

- Rosenblum, Robert. Ingres. London: Harry N. Abrams, 1990. ISBN 978-0-300-08653-9

- Rosenblum, Robert. "Ingres's Portraits and their Muses". In: Tinterow, Gary; Conisbee, Philip (eds). Portraits by Ingres: Image of an Epoch. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999. ISBN 978-0-300-08653-9

- Shelton, Andrew Carrington. Ingres and His Critics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0-521-84243-3

- Shelton, Andrew Carrington. "Ingres: Paris 1824–1834". In: Tinterow, Gary; Conisbee, Philip (eds). Portraits by Ingres: Image of an Epoch. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999. ISBN 978-0-300-08653-9

- Siegfried, Susan; Rifkin, Adrian. Fingering Ingres. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2001. ISBN 978-0-631-22526-3

- Toussaint, Hélène. Les Portraits d'Ingres: peintures des musées nationaux. Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 1985. ISBN 978-2-7118-0298-2

- Zamoyski, Adam. 1812, Napoleon's Fatal March on Moscow. London: Harper Perennial, 2005. ISBN 978-0-00-712374-2

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Portrait de Monsieur Bertin - Ingres - Louvre RF 1071. |

- Louis-François Bertin; at the Musée du Louvre

_-_Zelfportret_(1864)_-_28-02-2010_13-37-05.jpg)