Pole weapon

A pole weapon or pole arm is a close combat weapon in which the main fighting part of the weapon is fitted to the end of a long shaft, typically of wood, thereby extending the user's effective range and striking power. Because many pole weapons were adapted from agricultural implements or other tools in fairly large amount of abundance, and contain relatively little metal, they were cheap to make and readily available. When warfare breaks out and the belligerents have a poorer class who cannot pay for dedicated weapons made for war, military leaders often resort to the appropriation of tools as cheap weapons. The cost of training was minimal, since these conscripted farmers had spent most of their lives in the familiar use of these "weapons" in the fields. This made polearms the favored weapon of peasant levies and peasant rebellions the world over.

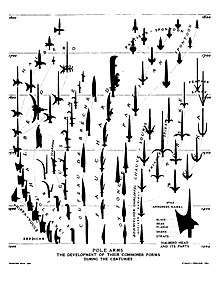

Pole arms can be divided into three broad categories: those designed for extended reach and thrusting tactics used in pike square or phalanx combat; those designed to increase leverage (thanks to hands moving freely on a pole) to maximize centrifugal force against cavalry; and those designed for throwing tactics used in skirmish line combat. Because their versatility, high effectiveness and cheap cost, polearms experimentation led to many variants and were the most frequently used weapons on the battlefield: bills, spears, glaives, guandaos, pudaos, poleaxes, halberds, harpoons, sovnyas, tridents, naginatas, war scythes and javelins are all varieties of pole arms.

Pole arms were common weapons on post-classical battlefields of Asia and Europe. Their range and impact force made them effective weapons against armored warriors on horseback, because they could be dismounted and/or penetrate said armor. The Renaissance saw a plethora of different varieties. Pole arms in modern times are largely constrained to ceremonial military units such as the Papal Swiss Guard or Yeomen of the Guard, or traditional martial arts. Chinese martial arts in particular have preserved a wide variety of weapons and techniques.

Classification difficulties

The classification of pole weapons can be difficult, and European weapon classifications in particular can be confusing. This can be due to a number of factors, including uncertainty in original descriptions, changes in weapons or nomenclature through time, mistranslation of terms, and the well-meaning inventiveness of later experts. For example, the word "halberd" is also used to translate the Chinese ji and also a range of medieval Scandinavian weapons as described in sagas, such as the atgeir. As well, all pole arms developed from three early tools (the axe, the scythe, and the knife) and one weapon, the spear.[1]

In the words of the arms expert Ewart Oakeshott,

Staff-weapons in Medieval or Renaissance England were lumped together under the generic term "staves" but when dealing with them in detail we are faced with terminological difficulty. There never seems to have been a clear definition of what was what; there were apparently far fewer staff-weapons in use than there were names to call them by; and contemporary writers up to the seventeenth century use these names with abandon, calling different weapons by the same name and similar weapons by different names. To add to this, we have various nineteenth century terminologies used by scholars. We must remember too that any particular weapon ... had everywhere a different name.[2]

While men-at-arms may have been armed with custom designed military weapons, militias were often armed with whatever was available. These may or may not have been mounted on poles and described by one of more names. The problems with precise definitions can be inferred by a contemporary description of Royalist infantry which were engaged in the Battle of Birmingham (1643) during the first year of English Civil War (in the early modern period). The infantry regiment that accompanied Prince Rupert's cavalry were armed:[3]

with pikes, half-pikes, halberds, hedge-bills, Welsh hooks, clubs, pitchforks, with chopping-knives, and pieces of scythes.

List of pole weapons

_-_zbirka_hladnog_oru%C5%BEja.jpg)

Ancient pole weapons

European

Asian

Dagger-axe

The dagger-axe, or gee (Chinese: 戈; pinyin: gē; Wade–Giles: ko; sometimes confusingly translated "halberd") is a type of weapon that was in use from Shang dynasty until at least Han dynasty China. It consists of a dagger-shaped blade made of bronze (or later iron) mounted by the tang to a perpendicular wooden shaft: a common Bronze Age infantry weapon, also used by charioteers. Some dagger axes include a spear-point. There is a (rare) variant type with a divided two-part head, consisting of the usual straight blade and a scythe-like blade. Other rarities include archaeology findings with 2 or sometimes 3 blades stacked in line on top of a pole, but were generally thought as ceremonial pole arms. Though the weapon saw frequent use in ancient China, the use of the dagger-axe decreased dramatically after the Qin and Han dynasties. The Ji combines the dagger axe with a spear. By the medieval Chinese dynasties, with the decline of chariot warfare, the use of the dagger-axe was almost nonexistent.

Ji

The ji (Chinese: 戟) was created by combining the dagger-axe with a spear. It was used as a military weapon at least as early as the Shang dynasty until the end of the Northern and Southern dynasties.

Ngao

The ngao or ngau (ง้าว,ของ้าว) is a Thai pole arm that was traditionally used by elephant-riding infantry and is still used by practitioners of krabi krabong. Known in Malay as a dap, it consists of a wooden shaft with a curved blade fashioned onto the end, and is similar in design to the Korean woldo. Usually, it also had a hook (ขอ) between the blade and shaft used for commanding the elephant. The elephant warrior used the ngao like a blade from atop an elephant or horse during battle.

Post-classical pole weapons

European

Danish axe

The Danish Axe is a weapon with a heavy crescent-shaped head mounted on a haft 4 to 6 ft (1.2 to 1.8 m) in length. Originally a Viking weapon, it was adopted by the Anglo-Saxons and Normans in the 11th century, spreading through Europe in the 12th and 13th centuries.[4] Variants of this basic weapon continued in use in Scotland and Ireland into the 16th century.[5] A form of 'Long Axe'.

Sparth axe

In the 13th century, variants on the Danish axe are seen. Described in English as a sparth (from the Old Norse sparðr)[6] or pale-axe,[7] the weapon featured a larger head with broader blade, the rearward part of the crescent sweeping up to contact (or even be attached to) the haft.

In Ireland, this axe was known as a Sparr Axe. Originating in either Western Scotland or Ireland, the sparr was widely used by the galloglass.[8] Although sometimes said to derive from the Irish for a joist or beam,[9] a more likely definition is as a variant of sparth.[10] Although attempts have been made to suggest that the sparr had a distinctive shaped head, illustrations and surviving weapons show there was considerable variation and the distinctive feature of the weapon was its long haft.[11]

Fauchard

A fauchard is a type of pole arm which was used in medieval Europe from the 11th through the 14th centuries. The design consisted of a curved blade put atop a 6-to-7-foot-long (1.8 to 2.1 m) pole. The blade bore a moderate to strong curve along its length; however, unlike a bill or guisarme, the cutting edge was on the convex side.

Guisarme

A guisarme (sometimes gisarme, giserne or bisarme) was a pole weapon used in Europe primarily between 1000 and 1400. It was used primarily to dismount knights and horsemen. Like most pole arms it was developed by peasants by combining hand tools with long poles, in this case by putting a pruning hook onto a spear shaft. While hooks are fine for dismounting horsemen from mounts, they lack the stopping power of a spear especially when dealing with static opponents. While early designs were simply a hook on the end of a long pole, later designs implemented a small reverse spike on the back of the blade. Eventually weapon makers incorporated the usefulness of the hook in a variety of different pole arms and guisarme became a catch-all for any weapon that included a hook on the blade. Ewart Oakeshott has proposed an alternative description of the weapon as a crescent shaped socketed axe.[12]

Glaive

A glaive is a pole arm consisting of a single-edged tapering blade similar in shape to a modern kitchen knife on the end of a pole. The blade was around 18 inches (46 cm) long, on the end of a pole 6 or 7 feet (180 or 210 centimetres) long.[13] However, instead of having a tang like a sword or naginata, the blade is affixed in a socket-shaft configuration similar to an axe head, both the blade and shaft varying in length. Illustrations in the 13th century Maciejowski Bible show a short staffed weapon with a long blade used by both infantry and cavalry.[14] Occasionally glaive blades were created with a small hook or spike on the reverse side.[15] Such glaives are named glaive-guisarme.

Voulge

A voulge (occasionally called a pole cleaver) is a curved blade attached to a pole by binding the lower two-thirds of the blade to the side of the pole, to form a sort of axe. Looks very similar to a glaive.

Svärdstav

A svärdstav (literally sword-staff) is a Swedish medieval pole arm that consists of a two-edged sword blade attached to a 2-metre (6 ft 7 in) staff. The illustrations often show the weapon being equipped with sword-like quillons.[16] The illustrations sometimes show a socket mount and reinforcing langets being used, but sometimes they are missing; it is possible this weapon was sometimes manufactured by simply attaching an old sword blade onto a long pole on its tang, not unlike the naginata.

Asian

Naginata

A naginata (なぎなた or 薙刀) is a Japanese pole arm that was traditionally used by members of the samurai class. A naginata consists of a wood shaft with a curved blade on the end; it is descended from the Chinese guan dao. Usually it also had a sword-like guard (tsuba) between the blade and shaft. It was mounted with a tang and held in place with a pin or pins, rather than going over the shaft using a socket.

Woldo

The Korean woldo was a variation of the Chinese guan dao. It was originally used by the medieval Shilla warriors. Wielding the woldo took time due to its weight, but in the hands of a trained soldier, the woldo was a fearsome, agile weapon famous for enabling a single soldier to cut down ranks of infantrymen. The woldo was continually in use for the military in Korea with various modifications made over the decades. Unlike the Chinese with the guan dao, the Koreans found the woldo unwieldy on horseback, and thus, it was specifically tailored to the needs of infantrymen. The Joseon government implemented rigorous training regimens requiring soldiers to be proficient with swordsmanship, and the use of the woldo. Though it was never widely used as a standard weapon, the woldo saw action on many fronts and was considered by many Korean troops to be a versatile weapon. Recently, a contemporary revival in various martial arts in Korea has brought interest into the application of the woldo and its history.

Guandao

A guandao or kwan tou is a type of Chinese pole weapon. In Chinese, it is properly called a yanyue dao (偃月刀), 'reclining moon blade'. Some believed it comes from the late Han Era and was supposedly used by the late Eastern Han Dynasty general Guan Yu, but archaeological findings have shown that Han dynasty armies generally used straight, single-edged blades, and curved blades came several centuries later. There is no reason to believe their pole arms had curved blades on them. Besides, historical accounts of the Three Kingdoms era describe Guan Yu thrusting his opponents down (probably with a spear-like pole arm) in battle, not cutting them down with a curved blade. The guandao is also known as the chun qiu da dao ('spring autumn great knife'), again probably related to the depiction of Guan Yu in the Ming dynasty novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms, but possibly a Ming author's invention. It consists of a heavy blade mounted atop a 5-to-6-foot-long (1.5 to 1.8 m) wooden or metal pole with a pointed metal counter weight used for striking and stabbing on the opposite end.

The blade is very deep and curved on its face, resembling a Chinese saber, or dao. Variant designs include rings along the length of the straight back edge, as found in the nine-ring guandao. The "elephant" guandao's tip curls into a rounded spiral, while the dragon head guandao features a more ornate design.

Podao

A podao, 'long-handled sabre', is a Chinese pole arm, also known as the zhan ma dao ('horsecutter sabre'), which has a lighter blade and a ring at the end. A podao is an infantryman's weapon, mainly used for cutting the legs off oncoming charging horses to bring down the riders.

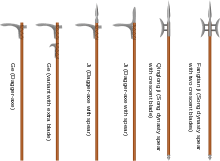

Fangtian ji

In the Song dynasty, several weapons were referred to as ji, but they were developed from spears, not from ancient ji. One variety was called the qinglong ji (Chinese: 青龍戟; lit.: 'cerulean dragon ji'), and had a spear tip with a crescent blade on one side. Another type was the fangtian ji (Chinese: 方天戟; lit.: 'square sky ji'), which had a spear tip with crescent blades on both sides.[17][18] They had multiple means of attack: the side blade or blades, the spear tip, plus often a rear counterweight that could be used to strike the opponent. The way the side blades were fixed to the shaft differs, but usually there were empty spaces between the pole and the side blade. The wielder could strike with the shaft, with the option of then pulling the weapon back to hook with a side blade; or, he could slap his opponent with the flat side of the blade to knock him off his horse.

Modern pole weapons

European

Corseque

A corseque has a three-bladed head on a 6–8 ft (1.8–2.4 m) haft which, like the partisan, is similar to the winged spear or spetum in the later Middle Ages.[19] It was popular in Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries. Surviving examples have a variety of head forms but there are two main variants, one with the side blades (known as flukes or wings) branching from the neck of the central blade at 45 degrees, the other with hooked blades curving back towards the haft. The corseque is usually associated with the rawcon, ranseur and runka. Another possible association is with the "three-grayned staff"[20] listed as being in the armoury of Henry VIII in 1547[21] (though the same list also features 84 rawcons, suggesting the weapons were not identical in 16th century English eyes). Another modern term used for particularly ornate-bladed corseques is the chauve-souris.[22]

Halberd

A halberd (or Swiss voulge) is a two-handed pole weapon that came to prominent use during the 14th and 15th centuries but has continued in use as a ceremonial weapon to the present day.[23] First recorded as "hellembart" in 1279, the word halberd possibly comes from the German words Halm (staff) or Helm (helmet), and Barte (axe). The halberd consists of an axe blade topped with a spike mounted on a long shaft. It always has a hook or thorn on the back side of the axe blade for grappling mounted combatants. Early forms are very similar in many ways to certain forms of voulge, while 16th century and later forms are similar to the pollaxe. The Swiss were famous users of the halberd in the medieval and renaissance eras,[24] with various cantons evolving regional variations of the basic form.[25]

Poleaxe

In the 14th century, the basic long axe gained an armour-piercing spike on the back and another on the end of the haft for thrusting. This is similar to the pollaxe of 15th century. The poleaxe emerged in response to the need for a weapon that could penetrate plate armour and featured various combinations of an axe-blade, a back-spike and a hammer. It was the favoured weapon for men-at-arms fighting on foot into the sixteenth century.[26]

References

- Dean, Bashford (1916). Notes on Arms and Armor. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 135.

- Oakeshott, Ewart (1980). European Weapons and Armour. Lutterworth Press. p. 52. ISBN 0-7188-2126-2.

- Warburton, Eliot, Memoirs of Prince Rupert, and the cavaliers: Including their private correspondence, now first published from the original MSS, 2, London: R. Bentley, p. 149 citing "Special Passages," No. xliii. (King's Collect.)

- Edge, David; John Miles Paddock (1988). Arms and Armour of the Medieval Knight. London: Defoe. p. 32. ISBN 1-870981-00-6.

- Caldwell, David (1981). "Some Notes on Scottish Axes and Long Shafted Weapons". In Caldwell, David (ed.). Scottish Weapons and Fortifications 1100-1800. Edinburgh: John Donald. pp. 262–276. ISBN 0-85976-047-2.

- Oakeshott (1980), p.47

- Nicolle, David (1996). Medieval Warfare Source Book Vol. 1. London: Arms & Armour Press. p. 307.

- Marsden, John (2003). Galloglas. East Linton: Tuckwell Press. p. 79. ISBN 1-86232-251-1.

- Marsden (2003), p.82

- OED

- Cannan, Fergus (2010). Galloglass 1250-1600. Oxford: Osprey. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-84603-577-7.

- Ewart Oakeshott (1980), p.53

- Oakeshott (1980), p.53

- The Morgan Library & Museum Online Exhibitions - The Morgan Picture Bible

- media:Battle from Holkham Bible.jpg

- media:Dolstein 1.gif

- Jiang Feng-wei (蔣豐維), Chinese weapons dictionary (中國兵器事典)

- Sadaharu Ichikawa (市川定春), Dictionary of the Weapon (武器事典)

- Norman, A. V. B.; Wilson, G. M. (1982). Treasures from the Tower of London : Arms and Armour. London: Lund Humphries. p. 67. ISBN 0-946009-01-5.

- Grayned meaning bladed

- Norman & Wilson (1982), p.67

- Oakeshott (1980), p.51.

- Oakeshott (1980), pp.47-48

- Douglas Miller : The Swiss at War 1300-1500, Osprey MAA 94, 1979

- Oakeshott (1980), p.47, fig 6

- Miles & Paddock, pp. 127–128

External links

- Spotlight: The Medieval Poleaxe by Alexi Goranov

- Fine, Tom (2001). "A summary of polearms". Retrieved 2 July 2020. (As used in NetHack.)