Aleksey Pleshcheyev

Aleksey Nikolayevich Pleshcheyev (Russian: Алексе́й Никола́евич Плеще́ев; 4 December [O.S. 22 November] 1825 – 8 October 1893) was a radical Russian poet of the 19th century, once a member of the Petrashevsky Circle.

Aleksey Pleshcheyev | |

|---|---|

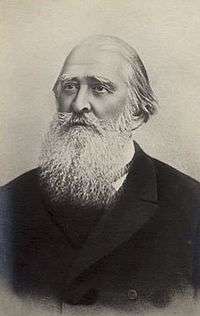

Pleshcheyev, 1880s | |

| Born | Aleksey Nikolayevich Pleshcheyev 4 December 1825 Kostroma, Russian Empire |

| Died | 8 October 1893 (aged 67) Paris, France |

| Occupation | Poet writer translator political activist |

| Alma mater | Saint Petersburg State University |

| Period | 1846–1993 |

| Subject | Political satire children poetry |

| Children | A. A. Pleshcheyev (1858–1944) |

Pleshcheyev's first book of poetry, published in 1846, made him famous: "Step forward! Without fear or doubt..." became widely known as "a Russian La Marseillaise" (and was sung as such, using French melody), "Friends' calling..." and "We're brothers by the way we feel..." were also adopted by the mid-1840s' Russian radical youth as revolutionary hymns.[1][2]

In 1849, as a member of Petrashevsky Circle, Pleshcheyev was arrested, sent (alongside Fyodor Dostoyevsky among others) to Saint Petersburg and spent 8 months in Peter and Paul Fortress. Having initially been given a death sentence, Pleshcheyev was then deported to Uralsk, near Orenburg where he spent ten years in exile, serving first as a soldier, later as a junior officer.

In his latter life, Pleshcheyev became widely known for his numerous translations (mostly from English and French) and also poems for children, some of which are now considered classic. Many of Pleshcheyev's poems have been set to music (by Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff among others) to become popular Russian romances.[2]

Biography

Alexey Nikolayevich Plescheev was born in Kostroma on 4 December, an heir to a noble family with ancient history and fine literary tradition. Among the future poet's ancestors were St. Alexis of Moscow and the 18th century writer Sergey Ivanovich Plescheev.[3][4]

Alexey's father Nikolai Sergeevich Plescheev was a state official, employed by Olonets, Vologda and Arkhangelsk governors.[5] He received a good home education and at the age of 13 joined the military school in Saint Petersburg. He left in 1834 without graduating and enrolled at Saint Petersburg University to study Oriental languages. Among his friends in Saint Petersburg were Fyodor Dostoyevsky, brothers Apollon and Valerian Maykovs, Andrey Krayevsky, Ivan Goncharov, Dmitry Grigorovich and Mikhail Saltykov-Schedrin. It was to one of his older friends, the rector of Saint Petersburg University Pyotr Pletnyov, that Pleshcheev sent his first collection of verse, receiving warm support.[2][6]

In 1845, infatuated with Socialist ideas, Pleshcheev joined the Petrashevsky Circle which included several writers – notably Dostoyevsky, Sergey Durov and Nikolay Speshnev, the latter exerting an especially strong influence upon the young man.[7] Pleshcheev wrote agitators' poetry (he was perceived by others in the circle as "our very own André Chénier") and delivered manuscripts of banned books to his comrades. In tandem with N.A.Mordvinov he translated the "Word of a Believer" by F.-R. de Lamennais which the Circle was planning to print and publish illegally.[8]

In 1845 due to financial difficulties, Pleshcheev left the University. In 1846 his first collection of poetry was published, including "Step forward! Without fear or doubt..." (Vperyod! Bez strakha y somnenya...) which quickly gained the reputation of a Russian La Marseillaise. The book resonated strongly with the Russian cultural elite's mood and Plescheev acquired the status of a revolutionary poet, whose mission was to "profess the inevitable triumph of truth, love and brotherhood."[9][10]

In 1847–1849 Pleshcheev's poems along with some prose, started to appear in magazines, notably, Otechestvennye Zapiski. Full of Aesopian language, some of them have still been credited as the first-ever reaction to the French Revolution of 1848 in the Russian literature.[5] In an 1888 letter to Chekhov Pleshcheev remembered:

For people of my kind – the late 1840s' men – France was very close to heart. With interior political scene shut off from any interference, what we were being brought upon and developed by were the French culture and the ideas of 1848. Later, of course, the disillusionment came, but to some of its principles we remained loyal.[11]

In the late 1840s Pleshcheev started to publish short stories and novelets. A natural school piece called "The Prank" (Shalost, 1848) bore evident Gogol influence, while "Friendly Advice" (Druzheskiye sovety, 1849) resembled "White Nights" by Dostoyevsky, the latter dedicated, incidentally, to Pleshcheev.[8][12]

In the late 1848 Plescheev started to invite members of the Petrashevsky Circle to his home. He belonged to the moderate flank of the organization, being skeptical about republican ideas and seeing Socialism as a continuation of the old humanist basics of Christianity.[13] In the spring of 1849 Pleshcheev sent a copy of the officially banned Vissarion Belinsky's letter to Gogol. The message was intercepted and on 8 April he was arrested in Moscow, then transported to Saint Petersburg. After spending nine months in the Petropavlovskaya fortress Pleshcheev found himself among 21 people sentenced to death. On 22 December, with other convicts, he was brought to the Semyonov Platz where, after a mock execution ceremony (later described in full detail by Dostoyevsky in his novel The Idiot), was given 4 years of hard labour. This verdict was softened and soon Pleshcheev went to the town of Uralsk where he joined the Special Orenburg Corps as a soldier, starting the service that lasted eight years.[14] Initially life in exile for him was hard and return to writing was out of question.[7] Things changed when Count Perovsky, his mother's old friend, has learnt of the poet's plight and became his patron. Pleshcheev got access to books and stroke several friendships, notably with the family of Colonel Dandeville (whose wife he fell in love with, leaving several poems dedicated to her), Taras Shevchenko, radical poet Mikhail Mikhaylov and a group of Polish exiles, among them Zygmunt Sierakowski. According to the latter's biographer, the circle's members discussed such questions as granting freedom to peasants and the abolition of corporal punishment in the Russian army.[2][15]

In March 1853 Pleshcheev asked to be transferred to the 4th infantry battalion and took part in several Turkestan expeditions endeavored by General Perovsky, participating in the siege of the Ak-Mechet fortress in Kokand. He was honoured for bravery and promoted to the rank of junior officer, then in 1856 was granted permission to become a civil servant. In May 1856 Pleshcheev retired from the Army, joined the Orenburg borderline Commission, then in September 1858 moved into the office of the Orenburg civil Governor's chancellery. That year he got a permission to visit Moscow and Saint Petersburg (making this 4 months trip with his wife Elikonda Rudneva whom he married a year later) and was returned all the privileges of hereditary dvoryanin he was stripped of eight years earlier.[1]

In exile Pleshcheev resumed writing: his new poems appeared in 1856 in The Russian Messenger under the common title Old Songs Sung in a New Way (Starye pesni na novy lad). In 1858, ten years on after the debut one, his second collection of verses was issued, a stand-out being the piece called "On Reading Newspapers", an anti-Crimean War message, in tune with the feelings common among the Ukrainian and Polish political exiles of the time. The collection's major themes were the author's feelings towards "his enslaved motherland" and the need for spiritual awakening of a common Russian man, with his unthinking, passive attitude towards life. Nikolai Dobrolyubov later reviewed the book with great sympathy and affection.[16] Then there was another long pause. Not a single poem from the 1849–1851 period remained and in 1853 Pleshcheev conceded he felt like he "was now forgetting how to write."[5]

In August 1859 Pleshcheev returned from his exile, settled in Moscow and started to contribute to Sovremennik, having maintained through the mutual friend Mikhail Mikhaylov strong personal contacts with Nekrasov, Chernyshevsky and Dobrolyubov. His works were also published by magazines Russkoye Slovo (1859–1854), Vremya (1861–1862) and Vek (1861), newspapers Denh (1861–1862) and Moskovsky Vestnik. In the late 1850s Pleshcheev started to publish prose, among his better known works being The Inheritance (Nasledstvo, 1857), Father and Daughter (Otets y dotch, 1857), Budnev (1858), Pashintsev (1859) and Two Careers (Dve Karjery, 1859), the latter three vaguely autobiographical novelets. In 1860 A.N.Pleshcheev's Novelets and Shorts Stories in 2 volumes came out, followed by two more collections of poetry, in 1861 and 1863, where he got closer to what scholars later describes as the "Nekrasov school" of protest verse. Contemporaries described him as a 'totally 1840s man' full of romanticism mixed with vague ideas of social justice. This alienated him from the emerging pragmatic radicals of the 1860s, and Pleshcheev admitted as much. "One is supposed to pronounce his very own New Word, but where it is supposed to come from?" he wondered, in a letter to Dostoyevsky.[7]

In December 1859 he was elected a member of the Russian Literary Society. A month earlier he joined the staff of Moskovsky Vestnik newspaper seeing it as his mission to make the paper an ally of Saint Petersburg's Sovremennik, and for almost two years was its editor-in-chief.[5] Pleshcheev's translations of "Dreams" (Sny) by Taras Shevtchenko was this paper's most politically charged publication. Pleshcheev continued contributing to Sovremennik up until the magazine's demise in 1866. His Moscow home became the center of literary and musical parties with people like Nikolai Nekrasov, Ivan Turgenev, Leo Tolstoy, Aleksey Pisemsky, Anton Rubinstein, Pyotr Tchaikovsky and actors of Maly Theatre attending regularly.[17][18]

In the early 1860s, Pleshcheev started to criticise the 1861 reforms which he initially was enthusiastic about and severed all ties with Mikhail Katkov's The Russian Messenger. His poetry became more radical, its leitmotif being the high mission of a revolutionary suffering from the society's indifference. The secret police in its reports mentioned Pleshcheev as a 'political conspirator' and in 1863 searched his house hoping to find evidence of his links with Zemlya i volya. There remained no documents supporting the case for Pleshcheev being Zemlya i volya member, but both Pyotr Boborykin and Maria Sleptsova later insisted that not only was he the active member of the underground revolutionary circle but kept printing facilities in his Moscow home where the Young Russia manifest has been printed.[5]

By the end of the decade almost all of his friends have been either dead or imprisoned and Pleshcheev (who in 1864 even had to join Moscow Postal office revision department) could see for himself no way to continue as a professional writer. Things started to change in 1868 when Nikolai Nekrasov, now the head of Otechestvennye Zapiski, invited Pleshcheev to move to Saint Petersburg and take the post of the reformed journal's secretary. After Nekrasov's death Pleshcheev became the head of the poetry department and remained in OZ up until 1884.[2][7]

As the magazine got closed, Pleshcheev became active as a Severny Vestnik organizer, the magazine he stayed with until 1890, helping a lot (with money, too) young authors like Ivan Surikov (who at one point was close to suicide), Garshin, Serafimovich, Nadson and Merezhkovsky.[19] In the 1870s and 1880s Pleshcheev made a lot of important translations from German, French and English and several Slavic languages. Among the works he translated were "Ratcliff" by Heinrich Heine, "Magdalene" by Hebbel, "Struenze" by Michael Behr. Stendhal's Le Rouge et le Noir and Émile Zola's Le Ventre de Paris were first published in Pleshcheev's translations.[14] In 1887 The Complete A.N.Pleshcheev was published, re-issued in posthumously, in 1894 by the poet's son.

Pleshcheev has been deeply engaged with the Russian theatre, was a friend of Alexander Ostrovsky and a one time the administrator of the Artistic Circle, an active member of the Russian Dramatist Society. He wrote thirteen original plays, most of them satirical miniatures dealing with the everyday life of a Russian rural gentry. Some of them (The Good Turn, Every Cloud Has Its Silver Lining, both 1860; The Happy Couple, The Woman Commander, both 1862; As It Often Happens, Brothers, both 1864) were produced by major Russian theatres. He adapted for stage productions more than thirty comedies of foreign authors.[2]

Pleshcheev's poetry for children, compiled in collections Snowdrop (1878) and Grandpa's Songs (1891), became immensely popular and for decades was featured in Russian textbooks. In 1861 with Fyodor Berg he compiled and published the Book for Children, then in 1873 (with N.A.Alekseev) another children's literary anthology, A Holiday Reading. He initiated the project involving the publication of seven textbooks in the Geography Sketches and Pictures.

Many of Pleshcheev's poems were set to music by composers like Rimsky-Korsakov, Musorgsky, César Cui, Grechaninov, Rakhmaninov and Tchaikovsky. The latter praised his children's cycle and cited it as a major source of inspiration. Among romances composed by Thaikovsky based on Pleshcheev's verses were "Oh, Not a Word, My Friend" (1869), "Sing Me the Same Song" (1872), "Only You" (1884), "If Only You'd Knew and Meekly Stars Were Shining Upon Us" (1886). Of Tchaikovsky's 16 Songs for Children (1883) 14 had Pleshcheev's lyrics.[2]

Last years

Not long before his death, in 1890, Pleshcheev inherited a fortune from his Penza relative Aleksey Pavlovich Pleshchhev. He's settled in the Parisian "Mirabeau" hotel with two of his daughters and started to invite his literary friends to guest with him, organising sight-seeing and restaurant tours around the city.[7] According to Zinaida Gippius, he's never changed (except for losing weight due to the progressing illness), "received this manna with noble indifference and remained the same cordial host we've known him for being when he lived in a tiny flat on Preobrazhenskaya square..." "What use wealth could be for me? Thankfully, now my children are saved from poverty and I myself can have a breath of air before I die," he was saying, according to Gippius.[3] Pleshcheev has donated money to the Russian Literary Fund, himself organized two funds, naming them after Belinsky and Chernyshevsky. He supported financially the families of Gleb Uspensky and Semyon Nadson and started to finance Russkoye Slovo, a magazine edited by Nikolai Mikhaylovsky and Vladimir Korolenko. One of his best friends in the later years Anton Chekhov was not a fan of Pleshcheev the poet but admired him as a person, viewing him as a "relic of the Old Russia".[2]

In July 1892 Pleshcheev informed Chekhov that his left arm and leg were now paralyzed. In Autumn 1893, severely ill, Pleshcheev attempted to make a travel to Nice, France, and died on the road, from a stroke. His body was taken to Moscow and he was buried in the Novodevichye Cemetery. The Russian authorities prohibited all kinds of obituaries, but huge a crowd, mainly of young people, gathered at the funeral, some of them (like Konstantin Balmont who pronounced a farewell speech) were to become well known years later.[7]

References

- "Russian Writers and Poets. Brief Biographical Dictionary (Русские писатели и поэты. Краткий биографический словарь. Moscow". ruscenter.ru. 2000. Archived from the original on 23 November 2010. Retrieved 22 March 2010.

- "Pleshcheev, Alexay Nikolayevich". The Krugosvet (Around the World) encyclopedia. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- Yuri Zobnin. Dmitry Merezhkovsky: Life and Moskow. Molodaya Gvardya. 2008. ISBN 978-5-235-03072-5. ZhZL (Lives of Distinguished People) Series, Issue 1291 (1091). P.101

- "2010 dates and jubilees". www.pskovlib.ru. Retrieved 22 March 2010.

- M.Y.Poliakov. "The Poetry by A.N.Plescheev (Поэзия А. Н. Плещеева)". plesheev.ouc.ru. Archived from the original on 11 January 2011. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- "About Pleshcheev (О Плещееве)". www.litera.ru. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- Nikolai Bannikov. Alexey Pleshcheev. Poems. Sovetskaya Rossia Publishers. Introduction. p.9

- "Bibliography of A.N. Pleshcheev (Плещеев А. Н.: Библиографическая справка)". plesheev.ouc.ru. Archived from the original on 11 January 2011. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- Otechestvennye Zapiski, 1846. № 10. Vol. IV. pp. 39–40

- Valerian Maykov. Literary Criticism. Leningrad. 1985. pp. 272–278.

- The Russian Library of Foreign Languages. Manuscripts dpt. The Chekhov Fund. A letter to Chekhov, September 12, 1888.

- V.L. Komarovich. The Youth of Dostoyevsky. The Past anthology. 1924. № 23.

- P.N. Sakulin. Alexey Nikolayevich Pleshcheev (1825–1893). // The History of the Russian 19th-century Literature. Moscow. Mir Publishers. 1911. Vol. 3. pp. 482–483

- Pyotr Veinberg (1907). "A. Pleshcheev". The Russian Autobiographical Dictionary // www.rulex.ru. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- J. Kowalski. Rewolucyjna demokracja rosyjska a powstanie styczniowe. W., 1955, str. 148.

- Nikolai Dobrolyubov. Works in 4 volumes. Moscow. 1950/ Vol. 1. Pp. 620, 623.

- The 1860s anthology, p. 454

- Russkaya Mysl, 1913, № 1, р. 149.

- "About Pleshcheev. Russian Writers and Poets. Moscow". plesheev.ouc.ru. 2000. Archived from the original on 11 January 2011. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

External links

![]()

- Aleksey Plescheyev: Poems (in Russian)

- Aleksey Plescheyev poetry at Stihipoeta (in Russian)