Penrhyn atoll

Penrhyn (also called Tongareva, Māngarongaro, Hararanga, and Te Pitaka) is an island in the northern group of the Cook Islands in the south Pacific Ocean. The northernmost island in the group, it is located at 1,365 km (848 mi) north-north-east of the capital island of Rarotonga, 9 degrees south of the equator. Its nearest neighbours are Rakahanga, and Manihiki, approximately 350 kilometres (220 mi) to the southwest.

| Native name: Tongareva | |

|---|---|

Aerial view of Penrhyn | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Central-Southern Pacific Ocean |

| Coordinates | 9°00′20″S 157°58′10″W |

| Archipelago | Cook Islands |

| Area | 9.8 km2 (3.8 sq mi) |

| Administration | |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 226 (2016) |

| Ethnic groups | Polynesian |

Geography

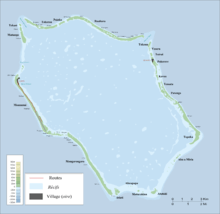

Penrhyn is a roughly circular coral atoll with a circumference of approximately 77 km (48 mi), enclosing a lagoon with an area of 233 square kilometres (90 sq mi). The atoll is atop the highest submarine volcano in the Cook Islands, rising 4,876 metres (15,997 ft) from the ocean floor.[1][2] The atoll is low-lying, with a maximum elevation of less than 5 metres (16 ft). The total land area is 9.84 square kilometres (3.80 sq mi). The population according to the 2001 census was 351 inhabitants, with a decrease by 2016 to only 226 inhabitants.[3]

Etymology

Penrhyn's original name was Tongareva. Academic research published by the Cook Islands Library and Museum says this is variously translated as "Tonga floating in space", "Tonga-in-the-skies" and "A way from the South".[4] However, the most commonly used name in English is Penrhyn after the Lady Penrhyn commanded by Captain William Crofton Sever, who passed by the island on 8 August 1788.[4] Penrhyn means "cape", "promontory" or "peninsula" in Welsh.[5] Another European name was Bennett Island.[4] Lady Penrhyn was one of a fleet of 11 ships which sailed from the Isle of Wight (off the south coast of the UK) to found the earliest convict colony in Australia.[4]

Demographics

Villages

Penrhyn Atoll has two villages. The main village of Omoka, seat of Penrhyn Island Council, is on Moananui Islet, on the western rim of the atoll, north of the airport. The village of Te Tautua is on Pokerekere Islet (also known as Pokerere or Tautua), on the eastern rim.

The inhabitants of the island are Christian, with 92% of the population belonging to the Cook Islands Christian Church while the remaining 8% adhere to the Roman Catholic Church.

History

Polynesians are believed to have lived on Penrhyn since at least 900 or 1000 AD. Following its discovery by Europeans, the Russian explorer Otto von Kotzebue visited the island in April 1816. He found its people ‘so numerous, in proportion to the island’ that he could not think how so many could ‘find subsistence’. Indeed, this was formerly one of the most densely inhabited atolls in Polynesia. Even, some 30 years after this first encounter with Europeans, a count in 1853 estimated 2500 people.[6] Kotzebue was followed by the American brig USS Purpose, under command of Lieutenant Commander Cadwalader Ringgold as part of the United States Exploring Expedition in February 1841. The brig Chatham under command of Edward Henry Lamont, ran aground at Penrhyn during a storm in January 1853. The London Missionary Society, which had begun missionary activities in the Cook Islands from 1821, sent a team to Penrhyn in 1854.

Robert Louis Stevenson visited Penrhyn in May 1890.

Slavery

In 1864, Penrhyn was almost completely depopulated by Peruvian expeditions. An estimated 1,000 men, women and children were taken to South America. Native pastors of the London Missionary Society had introduced Christianity from Rarotonga in 1854. The new religion had been accepted enthusiastically, and the villagers immediately started to build churches. Promises from the slavers of good pay and safe return offered a way to obtain money for churches, but all who accepted died in exile, virtually slaves.[7]

Another source states that in 1863, 410 inhabitants out of a total population of about 500 were kidnapped by blackbirding by the Peruvian blackbirders who were assisted by four native missionary teachers, who sold their people for five dollars per head. The missionaries accompanied the slaves to Peru as their interpreters; none of the 'stolen people' ever returned. [8]

Foreign claims

Penrhyn was officially annexed for Great Britain by Captain Sir William Wiseman of HMS Caroline on 22 March 1888. The island was considered to have a strategic location on the route of a proposed Trans-Pacific telegraphic connection between Canada and Australia.

The Cook Islands were a British protectorate 1888 to 1900, when annexed to New Zealand, until independence in 1965 when residents chose self-government in free association with New Zealand.[9]

From 1856 to 1980, the United States claimed sovereignty over the island under the Guano Islands Act. That claim had never been recognised by Britain, New Zealand or the Cook Islands and New Zealand sovereignty was recognised during World War II U.S. military operations involving the islands. On 11 June 1980, in connection with establishing the maritime boundary between the Cook Islands and American Samoa, the United States signed Cook Islands – United States Maritime Boundary Treaty acknowledging that Penryhn was under Cook Islands sovereignty.[10][11]

World War II

In early 1942 Japanese advances had placed the South Pacific air ferry route's initial path at some risk so that an alternate route was directed. In March Leif J. Sverdrup determined on a tour of potential island sites that Penrhyn was suitable and, though all land was owned by the local population and it was illegal to sell, use could be arranged and local labour could help build an airfield. U.S.Navy Seabees began work on a runway in July 1942 with aviation gasoline storage tanks added to the completed field.[10] Two additional runways were added later. During the war, US Navy PBY Catalina and USAAF B-24 Liberator bombers were stationed on the island and with about a thousand support personnel. A communications link through the island was established by the U.S. Army Signal Corps.[12] American forces were withdrawn in September 1946.

The US Army vessel Southern Seas struck an uncharted reef on 22 July 1942 and was severely damaged with flooded engine rooms and abandoned in Taruia Pass while on an island charting assignment in support of the construction. The ship was later salvaged by the Navy and commissioned for naval use.[13][14]

Cyclone Pat

In February 2010 much of Omoka was damaged by Cyclone Pat, but there were no serious casualties. Unfortunately the school was demolished and the community was left without teaching facilities. Tongareva's Women's Craft Guild loaned their meeting house, however this meant that five classes ranging from 3–16 years old had to be taught in a single room. New Zealand Aid paid completely for a new school to be constructed, Meitaki Poria.[15]

Economy and resources

The World War II airstrip is still used today as Tongareva Airport, with its initial 3000 meter runway reduced to 1700 meters. Weekly flights to the atoll by Air Rarotonga are subject to frequent cancellation due to lack of passengers or lack of fuel on Penrhyn for the return flight.

A large passage in the lagoon allows inter-island ships to enter the lagoon, and the island has become popular as a stopover for yachts crossing the Pacific from Panama to New Zealand. The inter-island Taio shipping company visits the island approximately every three months.

The locally produced Rito hats are woven from fibre from young coconut leaves which are stripped, boiled and dried resulting in a fine white leaf. Called rito weaving, the traditional items woven are Sunday church fans, small baskets and hats, the hats originally being a copy of the ones the sailors wore.[16] Weaving is now the major economic activity in both villages, with special designs being passed down through the families; both traditional and artificial dyes may be used.

Black pearl farming

Black pearl farming, together with mother of pearl, was previously the only significant economic activity on the island.[17] Pearl farming began in 1997-1998, but in 2000 algal blooms spread around the lagoon and a virus killed the pearl oysters. The stocks never recovered and the final harvest was in 2003, resulting in significant loss of equipment, outlay and resources.[18]

Food

The present population of the island rely on the ocean for most of their food as well as locally grown plants such as coconut, pawpaw, breadfruit and puraka (yam). Every morning (except on Sundays) men from the island head out in small tin boats to spear or trawl for fish for their families. The islanders' diet is supplemented by imported rice and flour shipped in from Rarotonga or Hawai'i. The boats are infrequent (usually every 3 months); however, the boat is often late and the people of Tongareva make do with what food they can provide for themselves, as their ancestors have done for centuries.

Energy

Electricity has been supplied by a generator in each village (Omoka 65 KVA, Te Tautua 35 KVA); these had been installed by Australian AID. Provision of diesel fuel required two long sea voyages: Auckland to Rarotonga, then onwards to the northern Cooks (ships travelled 7000 km each way). To save fuel electricity was always turned off overnight (11 pm to 6 am). The New Zealand Government (Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade) [19] decided to assist the Cook Islands Government by funding solar power arrays in all the northern atolls. The AID programme Uira Natura ko Tokerau was for NZ$20 million. The build was by PowerSmart Solar of New Zealand [20] Construction began 23 February 2015 and each village was solar powered by the end of May 2015. Some minor work is ongoing, but by the end of June 2015 all northern atolls will be fully on renewable energy. This greatly reduces the island's carbon footprint.

The Omoka solar farm and Te Tautua solar farm now provide 126kW and 42kW respectively.[21]

References

- "Tongareva (Penrhyn) Atoll - Cook Islands - Northern Group, South Pacific Ocean". www.ck. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- "Penrhyn, Cook Islands". www.cookislands.org.uk. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- "Cook Islands". City Population—Population Statistics for Countries, Administrative Areas, Cities and Agglomerations. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- Kloosterman, Alphons M. J. (1976). "Discoverers Of The Cook Islands And The Names They Gave". Cook Islands Library and Museum (web: Victoria University of Wellington). Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- http://geiriadur.ac.uk/gpc/gpc.html?penrhyn

- Crowe, Andrew (2018). Pathway of the Birds: The Voyaging Achievements of Māori and their Polynesian Ancestors. Auckland, New Zealand: Bateman. p. 135. ISBN 9781869539610.

- "Tongareva Island". www.janeresture.com. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- "Tongareva (Penrhyn) Atoll - Cook Islands - Northern Group, South Pacific Ocean". www.ck. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- Central Intelligence Agency (13 August 2013). "Cook Islands, World Factbook".

- Dod, Karl C. (1987). The Corps Of Engineers: The War Against Japan. United States Army In World War II. Washington, DC: Center Of Military History, United States Army. pp. 169, 171, 233. LCCN 66060004.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Office of The Geographer, Bureau of Intelligence and Research (2013). "Limits In The Seas No. 100; Maritime Boundaries: United States—Cook Islands and United States—New Zealand (Tokelau)" (PDF). Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- Thompson, George Raynor; Harris, Dixie R.; Oakes, Pauline M.; Terrett, Dulany (1957). The Technical Services—The Signal Corps: The Test (December 1941 to July 1943). United States Army In World War II. Washington, DC: Center Of Military History, United States Army. pp. 475–476. LCCN 56060003.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Section 3 – Publications, US Army Corps of Engineers" (PDF). U.S. Army Engineers in Hawaii. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 December 2013. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- "Southern Seas". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- Trade, New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and. "The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade acts in the world to make New Zealanders safer and more prosperous". New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- "Mahina Expeditions - Offshore Cruising Instruction". www.mahina.com. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- "Cook Islands Government Online: Pearls". cook-islands.gov.ck. Archived from the original on 23 July 2008. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- Ru Taime, formerly Ministry of Marine Resources at Tongareva

- Trade, New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and. "The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade acts in the world to make New Zealanders safer and more prosperous". New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- "Commercial Solar Power - Off-Grid Solar - Solar Power Systems". Powersmart Solar. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- "Cook Islands solar energy projects opened". Scoop. 13 May 2015. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Penrhyn Island. |