Pediculosis pubis

Pediculosis pubis (also known as "crabs" and "pubic lice"[1]) is a disease caused by the pubic louse, Pthirus pubis, a parasitic insect notorious for infesting human pubic hair. The species may also live on other areas with hair, including the eyelashes, causing pediculosis ciliaris. Infestation usually leads to intense itching in the pubic area. Treatment with topic agents such as permethrin or pyrethrin with piperonyl butoxide is effective. Worldwide, pediculosis pubis affects about 2% of the population.

| Pediculosis pubis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Crabs, pubic lice, phthiriasis, phthiriasis pubis |

| |

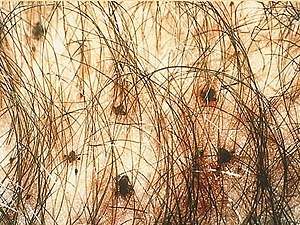

| Pubic lice in genital area | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

Signs and symptoms

The main symptom is itching, usually in the pubic-hair area, resulting from hypersensitivity to louse saliva, which can become stronger over two or more weeks following initial infestation.[2] In some infestations, a characteristic grey-blue or slate coloration macule appears (maculae caeruleae) at the feeding site, which may last for days.[2] Nits or live lice may also be visible to the unaided eye.[2][3] Adult lice can sometimes be seen crawling on the skin.[4]

Causes

Spread

Pubic lice are usually acquired by sexual activity.[2] Adults are more frequently infested than children. As with most sexually transmitted pathogens, they can only survive a short time away from the warmth and humidity of the human body.

Infestation in a young child or teenager may indicate sexual abuse.[5][6]

Characteristics and life cycle

Pubic lice have three forms: the egg (also called a nit), the nymph, and the adult. Nits are lice eggs. They can be hard to see and are found firmly attached to the hair shaft. They are oval and usually yellow to white. Pubic lice nits take about 6–10 days to hatch. The nymph is an immature louse that hatches from the nit (egg). A nymph looks like an adult pubic louse but it is smaller. Pubic lice nymphs take about 2–3 weeks after hatching to mature into adults capable of reproducing. To live, a nymph must feed on blood. The adult pubic louse resembles a miniature crab when viewed through a strong magnifying glass. Pubic lice have six legs; their two front legs are very large and look like the pincher claws of a crab - thus the nickname "crabs." Pubic lice are tan to grayish-white in color. Females lay nits and are usually larger than males.[4] To live, lice must feed on blood. If the louse falls off a person, it dies within 1–2 days. Pubic lice (Pthirus pubis) have three stages: egg, nymph and adult. Eggs (nits) are laid on a hair shaft. Females will lay approximately 30 eggs during their 3–4 week life span. Eggs hatch after about a week and become nymphs, which look like smaller versions of the adults. The nymphs undergo three molts before becoming adults. Adults are 1.5–2.0 mm long and flattened. They are much broader in comparison to head and body lice. Adults are found only on the human host and require human blood to survive. Pubic lice are transmitted from person to person most-commonly via sexual contact, although fomites (bedding, clothing) may play a minor role in their transmission.[2][7]

Diagnosis

A pubic louse infestation is usually diagnosed by carefully examining pubic hair for nits, nymphs, and adult lice.[2] Lice and nits can be removed either with forceps or by cutting the infested hair with scissors (with the exception of an infestation of the eye area). A magnifying glass or a stereo-microscope can be used for identification.[8]

Testing for other sexually transmitted infections is recommended in those who are infested with pubic lice.[2]

Treatment

Both over-the-counter and prescription medications are available for treatment of pubic lice infestations. A lice-killing lotion containing 1% permethrin or a mousse containing pyrethrins and piperonyl butoxide can be used to treat pubic ("crab") lice. These products are usually available over-the-counter without a prescription at a local drug store or pharmacy.[9][4] These medications are safe and effective when used exactly according to the instructions in the package or on the label.[10][8][2] Effectiveness of treatment is increased when the pediculicide is left on the skin and hair for at least an hour. A second round of treatment is recommended within the following seven to ten days to kill newly hatched nymphs.[8] Lindane is a second line treatment due to concerns of toxicity.[2] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) states that lindane should not be used by persons who have extensive dermatitis, women who are pregnant or lactating or children aged under two years.[11] The FDA similarly warns against use in patients with a history of uncontrolled seizure disorders and cautious use in infants, children, the elderly, and individuals with other skin conditions (e.g., atopic dermatitis, psoriasis) and in those who weigh less than 110 lbs (50 kg).[12][13]

Bedding and clothing should be laundered using hot water and sexual contact should be avoided until no signs of infestation exist.[4]

Pubic lice are primarily spread through sexual intercourse. Therefore, all partners with whom the patient has had sexual contact within the previous 30 days should be evaluated and treated, and sexual contact should be avoided until all partners have successfully completed treatment and are thought to be cured. Because of the strong association between the presence of pubic lice and classic sexually transmitted infections (STIs), patients may be diagnosed with other STIs.

Shaving the affected areas can be an important and helpful measure, as it interrupts the life cycle of the lice. Pubic lice cannot cling to the skin, only to hair. Thus, shaving has been reported as a helpful adjunct to the use of insecticides, like permethrin, pyrethrins and piperonyl butoxide. Shaving is also helpful, as the medicated creams and shampoos may not kill the eggs, whereas shaving can remove any remaining eggs. Shaving and treatment with insecticide should be complemented with careful and repeated cleaning of carpets, bedding, and clothes. Insecticidal sprays are also available to treat furniture made from fabrics, to which lice may cling.

The eyelids should be checked as well and treated accordingly. Infections of the eyelashes may be treated with either petroleum jelly applied twice daily for 10 days or malathion, phenothrin, and carbaryl.[2][8]

Epidemiology

Current worldwide prevalence has been very approximately estimated at two percent of the human population. Accurate numbers are difficult to acquire, because pubic lice infestations are not considered a reportable condition by many governments. Many cases are self-treated or treated discreetly by personal physicians, which further adds to the difficulty of producing accurate statistics.[14]

Although any part of the body may be colonized, crab lice favor the hairs of the genital and peri-anal region. Especially in male patients, pubic lice and eggs can also be found in hair on the abdomen and under the armpits, as well as on the beard and mustache, while in children they are usually found in eyelashes.

It has recently been suggested that an increasing percentage of humans removing their pubic hair has led to reduced crab louse populations in some parts of the world.[15][16]

Etymology

Infestation with pubic lice is also called phthiriasis or phthiriasis pubis, while infestation of eyelashes with pubic lice is called phthiriasis palpebrarum or pediculosis ciliarum.[17] The disease is spelled with phth, but the scientific name of the louse Pthirus pubis is spelled with pth (an etymologically incorrect spelling that was nonetheless officially adopted in 1958).[18]

Other animals

Humans are the only known hosts of this parasite,[19] although a closely related species, Pthirus gorillae, infects gorilla populations.[20]

References

- Ronald P. Rapini; Jean L. Bolognia; Joseph L. Jorizzo (2007). Dermatology. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- P. A. Leone (2007). "Scabies and pediculosis pubis: an update of treatment regimens and general review". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 44 (Suppl. 3): S153–S159. doi:10.1086/511428. PMID 17342668.

- John O'Donel Alexander (1984). Arthropods and Human Skin. Berlin: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-1356-0. ISBN 978-1-4471-1358-4.

- Prevention, CDC - Centers for Disease Control and (2 May 2017). "CDC - Lice - Pubic". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- Sidney Klaus; Yigal Shvil; Kosta Y. Mumcuoglu (1994). "Generalized infestation of a 3½-year-old girl with the pubic louse". Pediatric Dermatology. 11 (1): 26–28. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.1994.tb00068.x. PMID 8170844.

- José A. Varela; Luis Otero; Emma Espinosa; Carmen Sánchez; María Luisa Junquera; Fernando Vázquez (April 2003). "Phthirus pubis in a sexually transmitted diseases unit: a study of 14 years". Sexually Transmitted Infections. 30 (4): 292–6. doi:10.1097/00007435-200304000-00004. PMID 12671547.

- Prevention, CDC - Centers for Disease Control and (2 May 2017). "CDC - Lice - Pubic". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- Williams gynecology. Hoffman, Barbara L., Williams, J. Whitridge (John Whitridge), 1866-1931. (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. 2012. pp. 90–91. ISBN 9780071716727. OCLC 779244257.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "Pubic lice | Terrence Higgins Trust". www.tht.org.uk. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- Prevention, CDC - Centers for Disease Control and (2 May 2017). "CDC - Lice - Pubic". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Ectoparasitic infections. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. 2006" MMWR Recomm Rep 2006, August 10;55 (No. RR-11) 79-80.

- Lindane shampoo, USP, 1% prescribing information. Updated March 28, 2003.

- (FDA). Lindane Post Marketing Safety Review (PDF). Posted 2003.

- Alice L. Anderson; Elizabeth Chaney (2009). "Pubic lice (Pthirus pubis): history, biology and treatment vs. knowledge and beliefs of US College students". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 6 (2): 592–600. doi:10.3390/ijerph6020592. PMC 2672365. PMID 19440402.

- N. R. Armstrong; J. D. Wilson (2006). "Did the "Brazilian" kill the pubic louse?". Sexually Transmitted Infections. 82 (3): 265–266. doi:10.1136/sti.2005.018671. PMC 2564756. PMID 16731684.

- Bloomberg: Brazilian bikini waxes make crab lice endangered species, published 13 January 2013, retrieved 14 January 2013

- N. P. Manjunatha; G. R. Jayamanne; S. P. Desai; T. R. Moss; J. Lalik; A. Woodland (2006). "Pediculosis pubis: presentation to ophthalmologist as pthriasis palpebrarum associated with corneal epithelial keratitis". International Journal of STD & AIDS. 17 (6): 424–426. doi:10.1258/095646206777323445. PMID 16734970.

- Taxonomy of Human Lice

- "Pubic lice: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- Robin A. Weiss (2009). "Apes, lice and prehistory". Journal of Biology. 8 (2): 20. doi:10.1186/jbiol114. PMC 2687769. PMID 19232074.