Pavlović noble family

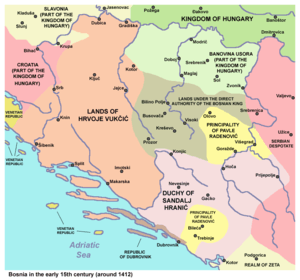

The Pavlović family, also Radinović[1] or Radenović[a], or Radinović-Pavlović, whose ancestors Jablanići got their name after their family estate at Jablan grad (Mezgraja, Ugljevik), was a medieval Bosnian family, whose feudal possessions extended from the Middle and Upper Drina river in the eastern parts of medieval Bosnia to south-southeastern regions of the Bosnian realm in Hum, and Konavle at the Adriatic coast. The family official residence and seat was at Borač and later Pavlovac, above the Prača river canyon, between present-day Prača, Rogatica and Goražde in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[3]

| Radinović-Pavlović[a] | |

|---|---|

| Noble house | |

Coat of arms of the House of Pavlović | |

| Parent house | Radinović |

| Country | Banate of Bosnia & Kingdom of Bosnia |

| Founded | 1391 |

| Founder | Pavle Radinović |

| Final ruler | Nikola Pavlović |

| Titles | Veliki Vojvoda Bosanski English: Grand Duke of Bosnia Vojvoda English: Duke Knez English: Lord Vlasteličić English: minor Lord |

| Style(s) | Veliki Vojvoda Bosanski English: Grand Duke of Bosnia |

| Religion | Bosnian Church[2] |

| Estate(s) | Borač-Pavlovac (main family estate) |

| Dissolution | 1463 Ottoman conquest |

History

Radin[a] Jablanić was a local lord of the Krivaja valley and Prača region, and father of family's founder Pavle Radenović, who ruled a territory in the east and south to southeastern parts of the Bosnian Kingdom,[1] from the late 14th century until his death in 1415.[4]

Pavle Radinović plotted against then king of Bosnia, Ostoja, and his Grand Duke, Sandalj Hranić, which led to his assassination by Sandalj in Kraljeva Sutjeska in 1415. He was buried somewhere in Vrhbosna, it is speculated in today's Sarajevo outskirts, between suburb of Dobrinja and village of Tilava, in the areal named "Pavlovac".[5]

Most prominent member of the family was Grand Duke of Bosnia, Radislav[a] Pavlović, son of Pavle.[2]

Family seat

Borač castle

The family hailed and ruled from Borač-Pavlovac. It's actually two castles rather than one, built in space of several decades (two generations) and few kilometers apart in distance from each others. These are simply known as Old Borač and New Borač or Pavlovac.[3][6][7][8]

Pavlovac castle

The new castle of Borač is actually called Pavlovac, and is considered to be a new structure also known Novi (English: New), or Novi Grad (English: New Town). Problem exist in correct dating of its construction, but some medieval charters suggest 1392, or late 14th century, as time of its construction, during Radislav Pavlović at the family's helm.[3][6][7][8]

Old Borač castle

However, historians are certain that another Radinović-Pavlović fortress existed, original and older Borač castle, which was built around 1244 in the 13th century and located just a few kilometers downstream the Prača river, near village Mesići, between villages of Borač i Brčigovo.[3][6][7][8]

Possessions

Possessions, estates and castles of Radinović-Pavlović family:[6]

| Borač | Popovo Polje, parts of | Konavle, parts of | ||

| Goražde | Bileća | Cavtat | ||

| Krivaja Valley, parts of | Vrhbosna, parts of | Žepa | ||

| Nišići | Trebinje | Ustikolina | ||

| Olovo | Srednje | Sokolac | ||

| Prača | Romanija | Višegrad | ||

| Rogatica |

Family tree

- Radin Jablanić (-1391), minor Landlord (Vlasteličić)

- Pavle Radinović (Founder) (1391–1415), Lord (Knez) and Duke (Vojvoda)[1]

- Petar I Pavlović (1415–1420), Duke (Vojvoda)

- Radislav Pavlović (1420–1441), Grand Duke of Bosnia (since 1441), Lord (Knez) and Duke (Vojvoda)

- Ivaniš Pavlović (1441–1450), Duke (Vojvoda)

- Petar II Pavlović (1450–1463), Duke (Vojvoda)

- Nikola Pavlović (1450–1463), Lord (Knez)

- Pavle Radinović (Founder) (1391–1415), Lord (Knez) and Duke (Vojvoda)[1]

Religion

Basic expression of loyalty and affiliation for all nobility during 14th and early 15th century, when Pavlović family ruled the central and eastern parts of Banat of Bosnia then Kingdom of Bosnia, was their loyalty to the monarch, kingdom, and Bosnian Church.

Similarly, all members of Pavlović family throughout 14th and early 15th century were members of this religion, except Ivaniš Pavlović, who briefly ventured into Catholicism.

So, it is known for certain that knyaz Pavle Radinović, his sons, duke Petar and knyaz and grand duke Radislav Pavlović, as well as grand duke's Radislav sons, duke Ivaniš, prince Nikola and knyaz Petar Pavlović were all members of Bosnian Church.[2]

Members and leaders of Bosnian Church had had important role and influence at Pavlović's family courts through generations, first at knyaz Pavla's Radinović court, and later at the court of Grand Duke of Bosnia Radislav Pavlović, as well as at his brother's duke Petar's court. This continued with Radislav's sons as well, duke Ivaniš Pavlović, prince Nikola and knyaz Petar.

Actually, it was Grand Duke of Bosnia, Radislav Pavlović, who significantly increased role and influence of Bosnian Church krstjani, their members and leaders with state affairs. Historical documents noted frequent appearance of Bosnian Church influential members every time political and economic relations needed mediation, whether within Bosnia and its magnates, or between Bosnia and its neighbors, and most notably in relation with Dubrovnik. These mediation were numerous especially between Bosnian elite and Dubrovnik, such as negotiations over sale of Radislav Pavlović's part of Konavale to Dubrovnik and mediation in ending Konavle war.[2]

Coat of arms

The subject and main reference of the book "Rodoslovne tablice i grbovi srpskih dinastija i vlastele" by group of Serbian authors from 1987,[9] in which, among other, Radinović-Pavlović coat of arms was discussed, are Illyrian Armorials, such as Fojnica and Ohmućević. These are in significant part fictional depiction of the medieval families coat of arms.

However, according to these authors, the "Illyrian Armorials" depict the family coat of arms as a fortified city with three towers, on both the shield and the crest, with red shield and golden city on it, while the city in the crest is red, as well as the mantling with an interior of golden. The "Ohmućević Armorial" added three golden fleur-de-lis in the shield, however, that interpretation is not in line with sphragistics, and is likely to be decorative.[10] The Pavlović family left six seals, which all have the same heraldic symbol, a tower, or fortified city. The oldest coat of arms is that of Pavle, dated to 1397, which has a fortified city with one tower. On the seals of his son, Radoslav, one has one tower (1432), the other three (1437), while Radoslav's son Ivaniš has three towers in his seal. The fortification is most likely modeled after Ragusan (today Dubrovnik) seals.[10] This seal was likely used as the family coat of arms, despite the fact that there are no authentic complete coat of arms with shield, helmet and crest.[10]

On the same subject other authors, like Ćiro Truhelka from 1914, and more recently Nada Grujić and Danko Zelić from 2010, and Amer Sulejmanagić from 2012, have different perspectives, from which they made different conclusions. Primarily, for them existence of the coat of arms (escutcheon, helmet and crest), created by Ratko Ivančić in 1427 and still visible at family palace in Dubrovnik, is not in dispute.

Thus, according to Croatian archaeologist Ćiro Truhelka (1865–1942) and his study "Osvrt na sredovječne kulturne spomenike Bosne" from 1914, the Illyrian Armorials, according to its "ideological-propagandic message", used the red color in the coat of arms, instead of Radoslav Pavlović's coat of arms in Ragusa which used ultramarine.[11]

On the same line Nada Grujić and Danko Zelić, in their study from 2010, state that Radislav Pavlović's coat of arms was in gold and lapis lazuli.[12]

Radoslav Pavlović's coat of arms at his palace in Ragusa was made by Ratko Ivančić in 1427, measuring 1,28x1,28 m.[13]

In two stećci in Boljuni near Stolac, there are engravings of a castle with three towers, which Šefik Bešlagić used to believe belonged to members of the family. On the other hand, there is an assumption that the necropolis at Pavlovac village, in Kasindo near Sarajevo, belonged to the family, thus, the resting place of the family remains unsolved.[10]

Annotations

- ^ Name: His surname is sometimes spelled Radenović (Serbian Cyrillic: Раденовић) and sometimes Radinović, being a patronymic from his father's name Raden or Radin (Jablanić). Same goes for his son Radoslav or Radislav (Pavlović). Different authors use different spelling, in most of the cases authors from Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia use Radin-Radinović-Radislav variant of these names, like, for example, one of the most important Bosnian medievalists Marko Vego 1957, same in Esad Kurtović 2009's book on pg.23 under reference 60. cited medieval charter with surname spelled Radinović ("Primjera radi, knez Pavle Radinović naveden je ispravno: “knezj Pavalj Radinović jzj bratiomj”; “Comes Paulus Radinović cum fratribus”, Šurmin, Hrvatski spomenici, 97; Klaić, Povelja, 61."); meanwhile authors from Serbia, like Jovan Radonić, use Raden-Radenović-Radoslav, sometimes even Radosav, variant. Authors from outside Serbo-Croatian speaking sphere use any of these variants indiscriminately, hence Fine 1994 uses Paul (Pavle) Radenović, while, for example, Heinrich Renner 1897, in his "Durch Bosnien und die Herzegovina kreuz und quer" on pg.129, writes Paul Radinović.

Sources

- Sulejmanagić, Amer (2012). "The Coat of Arms of the Pavlović Family". Bosna Franciscana. Aleja Bosne Srebrene 111, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina: Franjevačka teologija Sarajevo. 36/2012: 165–206.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Fine, John Van Antwerp (1994), The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, ISBN 978-0-472-08260-5CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Renner, Heinrich (1897), Durch Bosnien und die Herzegovina kreuz und quer (in German), Berlin D. Reimer (E. Vohsen)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vego, Marko (1957), Naselja bosanske srednjevjekovne države (in Bosnian), Sarajevo: SvjetlostCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kurtović, Esad (2009), Veliki vojvoda bosanski Sandalj Hranić Kosača (PDF) (in Bosnian), Sarajevo: Institut za istoriju univerzitet SarajevoCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- M.A. Thesis: "Slavni i velmožni gospodin knez Pavle Radinović" by Amer Maslo, Sarajevo 2018, mentor: Doc.Dr. Emir O. Filipović (available for download in .pdf both at faculty website and Academia repository)

- Aleksa Ivić; Dušan Mrđenović; Dušan Spasić; Aleksandar Palavestra (1987). Rodoslovne tablice i grbovi srpskih dinastija i vlastele. Belgrade: Nova knjiga.

References

- Maslo, Amer. "M.A. Thesis: "Slavni i velmožni gospodin knez Pavle Radinović" (available for download at faculty website)" (PDF). www.ff.unsa.ba (in Bosnian). Faculty of Philosophy of University of Sarajevo - History Department. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- Jurčević, Ivana (15 July 2016). "Srednjovjekovni odnosi crkve prema plemstvu u Bosni, poseban osvrt na obitelj Pavlović" (.pdf available in English for download). hrcak.srce.hr (in Croatian). Hum, časopis Filozofskog fakulteta Sveučilišta u Mostaru, Vol.11 No.15, 2016. pp. 112–135. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- "Borak (Han-stjenički plateau) necropolis with stećak tombstones in the village of Burati, the historic site". Commission to preserve national monuments (in Bosnian). Commission to preserve national monuments. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- Mihovil Mandić (December 1927). "Postanak Sarajeva". Naroda starina (in Croatian). Croatian State Archives. 6 (14): 4, 7. Retrieved 2012-09-11.

- Esad Kurtović. "Sandalj Hranić Kosača" (PDF). iis.unsa.ba (in Bosnian). Institut za istoriju Sarajevo - Univerzitet Sarajevo. Archived from the original (pdf) on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- Marko Vego (1957). Naselja bosanske srednjevjekovne države (in Bosnian). Sarajevo: Svjetlost. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- Alija Bejtić (1966). Rogatica, Srednji vijek (in Bosnian). Sarajevo: Svjetlost.

- Desanka Kovačević-Kojić (1987). Gradska naselja srednjovjekovne Bosanske države (in Bosnian). Sarajevo: Veselin Masleša.

- Ivić, Aleksa; Mrđenović, Dušan; Spasić, Dušan; Palavestra, Aleksandar. Rodoslovne tablice i grbovi srpskih dinastija i vlastele (in Serbian). Nova knj.

- Ivić et al. 1987, p. 189.

- Truhelka, Ćiro (1914). "Osvrt na sredovječne kulturne spomenike Bosne". Sarajevo, BiH: Glasnik Zemaljskog Muzeja BiH knjiga XXVI, 1914. p. 229.

Osvrt na sredovječne kulturne spomenike Bosne", 229. "Tako, barem u segmentu figura na štitu grba, možemo biti sigurni da ih je autor prototipa tzv. "Ilirskog grbovnika" manje-više vjerodostojno prenio. To se, naravno, ne može reći za boju štita grba. U skladu sa svojom ideološko–propagandnom porukom tzv. "Ilirskiog grbovnika" štit grba Pavlovića boji crvenom bojom nemanjićke kvazitradicije, dok je moćni bosanski magnat Radoslav Pavlović za svoj grb u Dubrovniku koristio skupi ultramarin.

Missing or empty|url=(help) - Nada Grujić, Danko Zelić, Palača vojvode Sandalja Hranića u Dubrovniku, Anali Dubrovnik 48, Dubrovnik, 2010, 70, nap. 71; “Mi znamo, da se je vojvoda Radoslav Pavlović trsio, da njegov dvor u Dubrovniku bude što sjajniji a na svom grbu, što je imao da ukrasi ulaz, nije žalio potrošiti ni zlata ni lapis lazuli, najskupocjeniji slikarski materijal one dobe...”

- Sulejmanagić, Amer (2012). "The Coat of Arms of the Pavlović Family". Bosna Franciscana (in Bosnian and English). Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina: Franjevačka teologija Sarajevo. 36/2012 (36): 165–206. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

"Duos cimerios de arma" koje je 1427. god. Ratko Ivančić klesao za Radoslavljevu palaču bili su dimenzija 2,5 lakta po visini i širini (1,28 x1,28 m)

External links

- U opštini Istočno Novo Sarajevo uništavaju stećke da bi se izgradio hotel / The East Novo Sarajevo Municipality is destroying the stećak tombstones to build a hotel - (video)

- / See how important cultural-historical heritage has been displaced in the territory of the Municipality of East Novo Sarajevo - part 1. to 6. (with photographs)