Patrick J. Hamrock

Patrick J. Hamrock[α] (1860-1939) was an Irish-born American soldier who served in multiple conflicts as part of the U.S. Army and Colorado National Guard. He led a portion of the militia that participated in the Ludlow Massacre, part of the 1913-1914 Colorado Coalfield War. After the First World War, he would serve as Colorado’s Adjutant General.

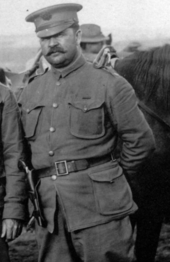

Patrick Hamrock | |

|---|---|

Patrick Hamrock in the field near the Ludlow Colony, 1914. | |

| Birth name | Patrick J. Hamrock |

| Born | 1860 Sligo, Ireland |

| Died | 25 August 1939 Denver, Colorado, U.S. |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service/ |

|

| Rank |

|

| Unit |

|

| Battles/wars | Colorado Coalfield War |

| Spouse(s) | Ellen McDonnell ( m. 1884)Annie Watson ( m. 1898) |

| Other work | Saloon owner |

Early life

Born in Caltragh, Sligo, Ireland in 1860 to James and Catherine Hamrock. Patrick moved to the California by 1880 and married Ellen McDonnell in 1884.[1]

Beginning of military career

Hamrock joined the U.S. Army as a member of the 7th Cavalry Regiment, a unit regularly involved in the battles of the Indian Wars against the Native American inhabitants of the Western United States during the latter-half of the 1800s. He was present during the Ghost Dance War against the Miniconjou and Hunkpapa Lakota, and participated 1890 campaign that included the Wounded Knee Massacre in South Dakota, where 200-300 Lakota were killed.[2]

Hamrock was involved in founding the Rocky Mountain Sharpshooters for the Spanish-American War, composed of volunteer marksmen from the Western US, but they never saw combat.[2] He later saw service in the Philippines during the Philippine–American War.[3] In the years that followed, Hamrock became the coach of the state rifle team, was promoted to major in the Colorado National Guard, and began operating a saloon in Denver.[4] He married Annie Watson there on 12 June 1898.[5]

Colorado Coalfield War

On 23 September 1913, the United Mine Workers of America declared a strike against the Rockefeller-owned Colorado Fuel and Iron company in southern Colorado in an effort to secure better pay and collective bargaining.[6] Up to 20,000 strikers were evicted from the company towns that dotted the coal-rich Sangre de Christo region, raising tent cities nearby with the help of the UMWA.[7] One of these towns-turned-tent cities was the Ludlow Colony.

What followed was several weeks of violence between strikers, non-striking and strikebreaking miners, hired-gun Baldwin-Felts detectives, and deputized militia. The Colorado National Guard was mobilized on 28 October and arrived in the strike zone by train before the end of the month.[8] The Major Hamrock was in charge of Company B of the National Guard, a 34-man detachment composed largely of enlisted CF&I mine guards and detectives stationed mostly at Cedar Hill near Tabasco.[9]

After six months of deployment to the largely isolated strike zone, the majority of the National Guardsmen were allowed to return to their livelihoods.[10] Company K, commanded by the amicable attorney-Captain Phillip Van Cise, withdrew from Ludlow, leaving Hamrock to send a 12 troops to fill their place.[4] Tensions in the region had decreased from a peak in October–November 1913, but rose again in March 1914 following the discover of a non-striking miner's body near the Forbes Colony of strikers. General John Chase, in command of the National Guard, order the strikers' colony razed and the men arrested, an action that indirectly resulted in two infants dying of exposure.[11]

Ludlow Massacre

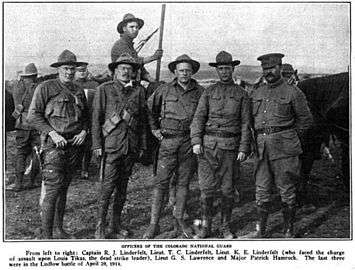

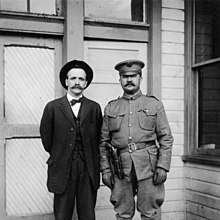

The troops at Ludlow under Hamrock's direction were stationed on Water Tank Hill, an elevated position that overlooked the colony. Alongside Hamrock's troops were militia under the command of Lieutenant Karl Linderfelt, who had previously seen combat against the strikers in the early stage of the conflict and also had authority over Company B.[9][12] These militia and troops were what remained after the bulk of the National Guard withdrew north, though the withdrawn troops were yet to be demobilized. Inside the 1,200-person Ludlow Colony, Cretan-born Greek striker Louis Tikas was helping to sooth tensions between the other Greek miners and a growingly-anxious Guard and militia presence.[2]

Following a tense day of Orthodox Easter festivities, on 20 April 1914, Hamrock received word from Linderfelt that an Italian woman was attempting to locate her husband named Tuttolimando, who was believed to live in the Ludlow Colony.[13][14] Hamrock dispatched a corporal and two enlisted men to search for him, and it became clear it Tikas had to be involved.[2] During Hamrock's conversation with Tikas, the Greeks in the camp grew restless. Soon, armed miners were spotted by Hamrock's adjutant Lieutenant Ray Benedict, leading Hamrock to send for Linderfelt's men at Cedar Hill.[2] Hamrock sent for reinforcements and a second machine gun to be brought to Ludlow from Cedar Hill, saying "put the baby in the buggy and bring it along."[15]

Hamrock again spoke to the miners via telephone and agreed to meet Tikas at the Colorado & Southern train station near the colony.[2] At 8:50 AM, Hamrock met Tikas at the agreed location, whereupon Tikas informed the troops and distraught woman that the man in question was not in the Ludlow Colony.[16] Greek miners moving in a flanking fashion towards an arroyo were seen by National Guardsmen who were emplacing the second machine gun. Tikas rushed back to the camp, reportedly carrying a white handkerchief in an attempt to prevent a fight.[17][18] Hamrock also failed to reach his own lines before the gunfire began.[19] Who fired the first shot is unclear,[20] but immediately the troops detonated three bombs intended to alert the Linderfelt detachment at Berwind and other militiamen at Delagua.[21][22] Hamrock would testify that he was among the first to man a machine gun, stating he had fired at points near the colony, rather than directly into it.[15]

In the all-day battle that followed, more than a dozen women and children were killed, mostly by smoke inhalation. Armed miners were also killed, as was Tikas. Tikas was found unarmed with his skull beaten in, and Linderfelt was seen carrying a broken Springfield rifle over his shoulder away from the scene.[23] The Ludlow Massacre, as it came to be known, sparked off the 10-Day War, the deadliest portion of the conflict. Major Hamrock ordered the bodies and charred remains of the camp left undisturbed for over half a day following the battle.[24] Mother Jones would list Hamrock as one of the parties who bore the greatest responsibility for the violence at Ludlow.[3]

Court-Martial

Hamrock was court-martialed for his actions at Ludlow on 13 May 1914. He was charged with murder, larceny, and other crimes associated with the death of Tikas and other unarmed strikers, as well as the twelve children and two women killed during the battle and militia-set fire that followed.[25] Linderfelt faced similar charges. Hamrock pleaded not-guilty to the charges. Pro-strikers decried what they said was "white-washing" when only militiamen testified on the first day of the court-martial. At Hamrock's court-martial, a Sergeant Davis testified that after Davis and a Corporal Mills arrested Tikas that Tikas ran and was shot under orders to execute any prisoners attempting to escape.[15] Both Hamrock and Linderfelt were never punished, despite a court determining that Linderfelt was guilty of the charges.[26]

Later life and death

Hamrock remained in the Colorado National Guard following the December 1914 end of the UMWA strike. On 20 August 1921, Hamrock was promoted to acting brigadier general after serving as a colonel and served as Colorado's Adjutant General.[27] In this capacity, Hamrock ordered Colorado Rangers to expel coal mining "agitators" during another strike in 1922.[28] Hamrock died on 25 August 1939 in Denver.[29]

References

- "Patrick Hamrock". Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- McGovern, George; Guttridge, Leonard. The Great Coalfield War. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1972. 213 p.

- Jones, Mary (1977). "The Autobiography of Mother Jones". p. 77. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- Papanikolas, Zeese. Buried Unsung: Louis Tikas and the Ludlow Massacre. Salt Lake City, Utah: University of Utah, 1982. 108 p.

- "Colorado Marriages 1858-1939 U-V-W". Denver Public Library Digital Collections. 2004. p. 749. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- Boor Tonn, Mari (2011). ""From the Eye to the Soul": Industrial Labor's Mary Harris "Mother" Jones and the Rhetorics of Display". Rhetoric Society Quarterly. 41 (3): 231–249. doi:10.1080/02773945.2011.575325. JSTOR 23064465.

- Martelle, Scott. Blood Passion: The Ludlow Massacre and Class War in the American West. New Brunswick, New Jersey and London: Rutgers University Press, 2007. bib., illus., index, 266 p.

- Colorado Adjutant General's Office (1914). The Military Occupation of the Coal Strike Zone of Colorado by the National Guard, 1913-1914 (Report).

- McGovern & Guttridge, 211.

- "A History of the Colorado Coal Field War". Colorado Coal Field War Project. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- Andrews, Thomas G. Killing for Coal: America's Deadliest Labor War. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2008. 270 p.

- Andrews, 270.

- Andrews, 271.

- Martelle, 161.

- "FIRED MACHINE GUN IN LUDLOW BATTLE; Trained It on a Point Near Colorado Miners' Tents, Major Hamrock Testifies". The New York Times. 21 May 1914. p. 4. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- McGovern & Guttridge, 214.

- Papanikolas, 218.

- Martelle, 163.

- McGovern & Guttridge, 215.

- Andrews, 272.

- Papanikolas, 219.

- Martelle, 164.

- Papanikolas, 226.

- "30 BESIEGED IN MINE MAY BE SUFFOCATED; Mouth of Slope Blocked by Dynamite Explosions Caused by Strikers". The New York Times. 23 April 1914. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- "MILITIA ACCUSED OF CRIMES". Press Democrat. Santa Rosa, California. 14 May 1914. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- McGovern & Guttridge, 285-287.

- "Official National Guard Register, 1922". 1922. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- "RANGERS TO DRIVE UNION AGITATORS OUT". Fort Collins Courier. 10 April 1922. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- "Denver Public Library microfilm obituaries 1944-1959". Denver Public Libraries Digital Collection. 2010. p. 562. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

Notes

- 1.^α Patrick Hamrock's name in academic literature is generally given as "Patrick J. Hamrock," such as by Martelle. However, McGovern and Guttridge refer to him as "Patrick C. Hamrock." Official military records from 1922 list him as "Patrick J. Hamrock."