Paris architecture of the Belle Époque

The architecture of Paris created during the Belle Époque, between 1871 and the beginning of the First World War in 1914, was notable for its variety of different styles, from neo-Byzantine and neo-Gothic to classicism, Art Nouveau and Art Deco. It was also known for its lavish decoration and its imaginative use of both new and traditional materials, including iron, plate glass, colored tile and reinforced concrete. Notable buildings and structures of the period include the Eiffel Tower, the Grand Palais, the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, the Gare de Lyon, the Bon Marché department store, and the entries of the stations of the Paris Metro designed by Hector Guimard.

.jpg)

The architectural style of the Belle Époque often borrowed elements of historical styles, ranging from neo-Moorish Palais du Trocadéro, to the neo-Renaissance style of the new Hôtel de Ville, to the exuberant reinvention of French 17th and 18th century classicism in the Grand Palais and Petit Palais, the new building of the Sorbonne. The new railroad stations, office buildings and department stores often had classical facades which concealed resolutely modern interiors, built with iron frames, winding staircases, and large glass domes and skylights made possible by the new engineering techniques and materials of the period.

The Art Nouveau became the most famous style of the Belle Époque, particularly associated with the Paris Metro station entrances designed by Hector Guimard, and with a handful of other buildings, including Guimard's Castel Béranger (1898) at 14 rue La Fontaine, in the 16th arrondissement, and the ceramic-sculpture covered house by architect Jules Lavirotte at 29 Avenue Rapp (7th arrondissement). [1] The enthusiasm for Art Nouveau did not last long; in 1904 the Guimard Metro entrance at Place de l'Opera it was replaced by a more classical entrance. Beginning in 1912, all the Guimard metro entrances were replaced with functional entrances without decoration.[2]

The most famous church of the period was the Basilica of Sacré-Coeur, built over the entire span of the Belle Epoque, between 1874 and 1913, but not consecrated until 1919. It was modeled after Romanesque and Byzantine cathedrals of the early Middle Ages. The first church in Paris to be constructed of reinforced concrete was Saint-Jean-de-Montmartre, at 19 rue des Abbesses at the foot of Montmartre. The architect was Anatole de Baudot, a student of Viollet-le-Duc. The nature of the revolution was not evident, because Baudot faced the concrete with brick and ceramic tiles in a colorful Art nouveau style, with stained glass windows in the same style.

A new style, Art Deco, appeared at the end of the Belle Époque and succeeded Art Nouveau as the dominant architectural tradition in the 1920s. Usually built of reinforced concrete in rectangular forms, crisp straight lines, with sculptural detail applied to the outside rather than as part of the structure, it drew from classical models and stressed functionality. The Théâtre des Champs-Élysées (1913), designed by Auguste Perret, was the first Paris building utilizing Art Deco. Other innovative buildings in the new style were built by Henri Sauvage, using reinforced concrete covered with ceramic tile and step-like structures to create terraces. By the 1920s, it had become the dominant style in Paris.

Architecture of the Paris Expositions

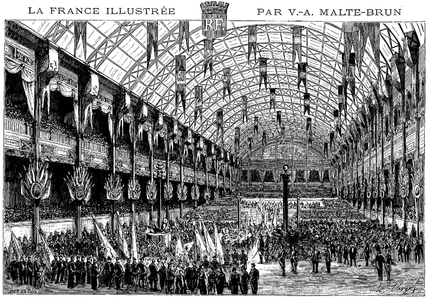

The Palace of Industry from the 1878 Exposition. New technologies displayed inside included Alexander Graham Bell's telephone and Thomas Edison's phonograph.

The Palace of Industry from the 1878 Exposition. New technologies displayed inside included Alexander Graham Bell's telephone and Thomas Edison's phonograph. The Trocadero Palace, built in a neo-Moorish or neo-Byzantine style for the Universal Exposition of 1878, was also used in the Expositions of 1889 and 1900.

The Trocadero Palace, built in a neo-Moorish or neo-Byzantine style for the Universal Exposition of 1878, was also used in the Expositions of 1889 and 1900. The Gallery of Machines of the 1889 Exposition. It was the largest covered space in the world when it was built.

The Gallery of Machines of the 1889 Exposition. It was the largest covered space in the world when it was built.

Three great international expositions were held in Paris during the Belle Époque, designed to showcase modern technologies, industries and the arts. They attracted millions of visitors from around the world, and influenced architecture far outside France.

The first, the Paris Universal Exposition of 1878, occupied the Champ-de-Mars, the hill of Chaillot on the other side of the Seine, and the esplanade of the Invalides. The central building, the Palais de Trocadero, was constructed in a picturesque neo-Moorish or neo-Byzantine style by architect Gabriel Davioud, whose other notable works, built for Napoleon III, included the two theaters on the Place du Chatelet and the Fontaine Saint-Michel. The palace was used in all three Expositions of the Belle Époque, but was finally demolished in 1936 to make room for the modern Palace of Chaillot.

The Paris Universal Exposition of 1889, celebrating the centenary of the French Revolution, was much larger than the 1878 Exposition, and gave Paris two revolutionary new structures; The Eiffel Tower was the tallest structure in the world, and became the symbol of the Exposition. The tower brought lasting fame to its constructor, Gustave Eiffel. The architects of the tower, including Stephen Sauvestre, who designed the graceful curving arches of the base, the glass observation platform on the second level and the cupola at the top, remain nearly unknown.[3]

An equally significant building constructed for the fair was the Galerie des machines, designed by architect Ferdinand Dutert and engineer Victor Contamin. It was located at the opposite end of Champ-de-Mars from the Eiffel Tower. It was reused at the exposition of 1900 and then destroyed in 1910. At 111 meters, the Galerie (or "Machinery Hall") spanned the longest interior space in the world at the time, using a system of hinged arches (like a series of bridge spans placed not end-to-end but parallel) made of iron.[4] It was used again in the 1900 Exposition. When the 1900 Exposition ended, the French government offered to move the structure to the edge of Paris, but the city government chose to demolish it in order to resell the building materials. It was torn down in 1909.[5]

The Grand Palais (1900) had a neoclassical facade concealing a cathedral-like glass and iron exhibit hall.

The Grand Palais (1900) had a neoclassical facade concealing a cathedral-like glass and iron exhibit hall. The interior of the Grand Palais was an enormous gallery of sculpture during the 1900 Exposition

The interior of the Grand Palais was an enormous gallery of sculpture during the 1900 Exposition- The stairway of honor of the Grand Palais, built of copper

The 1900 Exposition was the largest and most successful of them all, occupying most of the space along the Seine from the Champs-de-Mars and Trocadero to the Place de la Concorde. The Grand Palais, the largest exhibition hall, was designed by architect Henri Deglane, assisted by Albert Louvet. Deglane had been an assistant to Dufert, the builder of the Palace of Machines. The new building contained an enormous gallery, whose arches converged to create a monumental glass dome. Though its visible iron framework made it appear very revolutionary and modern, much of its iron work purely decorative; the gothic iron columns which seemed to support the dome did not carry any weight; the weight was actually distributed to reinforced columns hidden behind the balconies. The facade was massive and neoclassical, with towering rows of columns supporting two sculptural ensembles. It served both to give a strong vertical element to balance the great width of the building, and to conceal the glass and steel structure behind. It was also designed to be in harmony with the historic buildings nearby, including the buildings around the Place de la Concorde and the 17th century church of Les Invalides on the other side of the Seine. The facade was greatly admired and widely imitated; a similar facade was given to the New York Public Library in 1911.

The most prominent architectural feature inside the Grand Palais was the Grand Stairway of Honor, which overlooked the main floor, which at the 1900 Exposition contained an exhibition of monumental sculpture. It was perfectly classical in style. It was originally intended to be built of stone. Deglane and Louvet built a model of plaster and stucco on a metal frame, and then decided, to make it harmonious with the rest of the interior, to make it completely out of copper, highly ornamental and very expensive. Using iron in place of stone traditionally reduced building costs, but in the case of the Grand Palais, because of the enormous amounts of iron used, it actually increased the cost. The construction of the Grand Palais used 9,507 tons of metal, compared with 7,300 tons for the Eiffel Tower. [6]

The grand entrance of the Petit Palais, and its impressive colonnade

The grand entrance of the Petit Palais, and its impressive colonnade One of the reinforced concrete stairways of the Petit Palais

One of the reinforced concrete stairways of the Petit Palais The use of reinforced concrete and large windows and skylights gave the interior of the Petit Palais an abundance of light and space

The use of reinforced concrete and large windows and skylights gave the interior of the Petit Palais an abundance of light and space

The Petit Palais, designed by Charles Giraud, was directly across from the Grand Palais, and had a similar monumental entrance (both entrances were designed by Giraud). Both buildings also had rows of massive columns, which served as a powerful vertical element to balance the great width of the buildings, and also concealed the modern iron framework behind. However, the most original feature of the Petit Palais was the interior; Girault eliminated the traditional walls and spaces and made full use of reinforced concrete to create majestic winding staircases and wide entry ways, built enormous skylights and windows that provided abundant light, and turned the interior into a single unified space. [7]

Residential buildings

- The Castel Béranger by Hector Guimard (1899)

Entrance of the Castel Béranger

Entrance of the Castel Béranger.jpg) Lavirotte Building by Jules Lavirotte at 29 Avenue Rapp (1901)

Lavirotte Building by Jules Lavirotte at 29 Avenue Rapp (1901) Entrance to Lavirotte Building (1901)

Entrance to Lavirotte Building (1901) Reinforced concrete and ceramic house by Auguste Perret at 25 bis Rue Franklin, 16th arr. (1904)

Reinforced concrete and ceramic house by Auguste Perret at 25 bis Rue Franklin, 16th arr. (1904) The Hôtel Guimard at 122 Avenue Mozart (1909–1913)

The Hôtel Guimard at 122 Avenue Mozart (1909–1913)

As the end of the 19th century approached, many architectural critics complained that the uniform style of apartment buildings imposed by Haussmann on the new boulevards of Paris under Napoleon III was monotonous and uninteresting. Haussmann had required that apartment buildings have the same height, and that facades have the same general design and color of stone. In 1898, to try to bring more variety to the appearance of the boulevards, the City of Paris sponsored a competition for the best new apartment building facade. One of the first winners in 1898 was the thirty-one year old architect Hector Guimard (1867–1942). Guimard's building, built between 1895 and 1898, was called the Castel Beranger, and was located at 14 rue de la Fontaine in the 16th arrondissement. It contained thirty-six apartments, and each one was different architecturally. Guimard thought out and designed every aspect of the building himself, down to the door-knobs. He introduced an abundance neo-Gothic decorative elements, made of wrought iron or sculpted in stone, which gave it a personality different from any other Paris building. Guimard was also an expert at the new art of public relations, and he persuaded critics and the public that the new building heralded a revolution in architecture. Before long, based on his work and his publicity, he became the most famous of Paris Belle Époque architects. [8]

In 1901, the facade competition was won by another remarkable architect, Jules Lavirotte (1864–1924), for an apartment building whose facade featured ceramic decoration by Alexandre Bigot, a chemistry professor who became interested in ceramics at the Chinese exhibition at the 1889 International Exposition, and who started his own firm to make ceramic sculpture and decoration. The Lavirotte Building, located at 29 Avenue Rapp in the 7th arrondissement, became its most prominent advertisement. The Lavirotte Building was more a piece of sculpture than a traditional building. Unlike other Paris buildings, whose decoration was usually modeled a particular period or style, the Lavirotte Building, like the opera house of Charles Garnier, was unique; there was nothing else in Paris like it. The front entrance was surrounded by ceramic sculpture, and upper floors were entirely covered with ceramic tile and decoration. The building also featured a novel construction feature; the walls were built of hollow bricks; iron rods were inserted inside, and the bricks were filled with cement. For the exterior decoration, Lavirotte commissioned a team of sculptors and craftsmen. [9]

In 1904, the architect Auguste Perret used reinforced concrete to create a revolutionary new building at 25 bis on Rue Franklin in the 16th arrondissement. Reinforced concrete had been used before in Paris, usually to imitate stone. Perret was among the first to take full advantage of the new architectural forms it could make. The building was on a small site, but offered an exceptional view of Paris. To maximize the view, Perret built the house of with large windows framed with ceramic decorative plaques made by Alexandre Bigot, mounted on reinforced concreter, so that facade of the building was almost entirely windows. The plaques were of a neutral color, to give the appearance of stone. By adding an excèdre on the facade, he was able to create five apartments on each floor, each with the view, whereas a flat traditional facade would have had only four.

Near the end of the Belle Époque, Hector Guimard changed his style radically from what it had been when he built Castel Béranger in 1899. Between 1909 and 1913 he built his own house, the Hôtel Guimard, on Avenue Mozart in the 16th arrondissement. He abandoned the colors and decorations of the earlier style, and replaced with a building made masonry and stone which seemed to have been sculpted by nature. Hector had been influenced by a meeting when he was young with the Belgian art nouveau architect Victor Horta, who told him that the only aspect of nature that an architect should imitate was the curve of the stems of flowers and plants. Guimard had followed Horta's advice in the decor of Castel Beranger; in the Hôtel Guimard he followed this advice in the wrought-iron railings, the door and window frames and curves of the building itself, which seemed to be a living thing. [10]

The architect Paul Guadet (1873–1931) was another pioneer in the use of reinforced concrete. He was the architect of several telephone exchanges for the Ministry of the Post Office, remarkable for their clean lines and modern appearance. The Post Office was his employer from 1912 until his death. The facade of his own house, at 95 boulevard Murat in the 16th arrondissement, is remarkably modern; it is almost all windows, framed by concrete columns, discreetly decorated with colored ceramic tiles.

On the streets of Paris, an elegant neo-classicism coexisted comfortably with the new styles. The Hotel Camondo. now the Musée Nissim de Camondo), at 63 Rue Monceau in the 8th arrondissement, was designed by René Sergent (1865–1927). He was a graduate of the École special d'architecture, a school founded in opposition to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts and to the Art Nouveau movement, dedicated to preserving the spirit of Viollet-le-Duc, and training architects who were skilled in both the arts and engineering. It was completed in 1911. The exterior was pure Louis XVI, inspired by the Petit Trianon and borrowing many architectural details from that building. The interior had the most modern technology available, including electric lighting and a very early use of indirect lighting. [11]

The Hôtel de Choudens, at 21 Rue Blanche in the 9th arrondissement, was another neoclassical house, designed by Charles Girault (1851–1932), who had won the Prix de Rome and who had won fame designing the Petit Palais for the 1900 Exposition. It was built for Paul de Choudens, a writer of librettos and musical editor. In addition to the traditional reception rooms, the ground floor included a room designed for musical auditions. It was inspired largely by the houses of the Italian Renaissance, but Girault added modern touches in the curving windows, the floral wrought-iron decoration, and a series of terraces in the rear facing the garden.

Department stores

.jpg) Interior of the Bon Marché department store (1875)

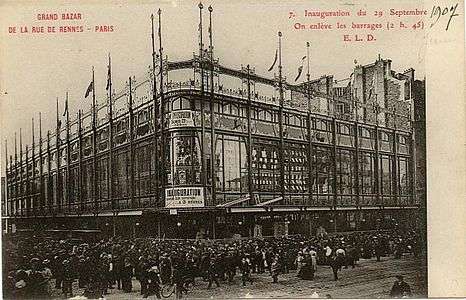

Interior of the Bon Marché department store (1875) The Grand Bazar on the Rue de Rennes on its opening day (1906)

The Grand Bazar on the Rue de Rennes on its opening day (1906)- A floral Art Nouveau sign by artist Eugene Grasset for the facade of La Samaritaine (1903–1907)

The art-nouveau cupola of Galeries Lafayette (1912) provides natural light to the levels around the courtyard below.

The art-nouveau cupola of Galeries Lafayette (1912) provides natural light to the levels around the courtyard below.

The modern department store was born in Paris in 1852, shortly before the Belle Époque, when Aristide Boucicaut enlarged a medium-sized variety store called Au Bon Marché, using innovative new means of marketing and pricing, including a mail order catalog and seasonal sales. When Boucicaut took charge of the store in 1852, it had an income of 500,000 francs and twelve employees. Twenty years later it had 1,825 employees and an income of more than 20 million francs. In 1869 Boucicault began constructing a much larger store, with an iron frame, a central courtyard covered with a glass skylight, on the rue de Sèvres. The architect was Louis Boileau, who received some assistance from the engineering firm of Gustave Eiffel. After more enlargements and modifications, the building was finished in 1887, and became the prototype for other department stores in Paris and around the world.[12]

Other department stores appeared to rival Au Bon Marché: au Louvre in 1865; the Bazar de l'Hotel de Ville (BHV) in 1866, Au Printemps in 1865; La Samaritaine in 1870, and Galeries Lafayette in 1895. Between 1903 and 1907 the architect Frantz Jourdain created the interior and facades of the new building of La Samaritaine. He commissioned the decorative artist Eugene Grasset to create the huge inscription of the name of the store, against a floral background. He used an abundance of enameled tiles and a brightly colored interior and exterior, using yellow and orange panels to contrast with the vertical blue columns, which ended in a Gothic-inspired top story. The rectangular metal framework of the exterior was entirely covered and brightened with floral designs. The original 1907 structure had two towers with domes and spires, like a Chateau of the Loire; these were demolished when the store was enlarged toward the Seine in the 1920s. In the 1930s the architect Henri Sauvage updated the facade and replaced many Art Nouveau features with art deco elements. [13]

Gas lighting and early electric lighting presented serious dangers of fire for early department stores; architects of the new stores used huge ornamental glass skylights whenever possible to fill the stores with natural light, and designed the balconies around the central courts to provide the maximum of light to each section. The Galeries Lafayette store on Boulevard Haussmann, finished in 1912, combined skylights over courtyards with balconies with undulating railings, which gave the interiors the rich roccoco effect of a baroque palace. Before the store was enlarged and modernized, it had several vertical great halls filled with light from richly decorated glass cupolas. [14]

Office buildings

The safety elevator had been invented in 1852 by Elisha Otis, making tall buildings practical. The first skyscraper, the Home Insurance Building, a ten-story building with a steel frame. was built in Chicago in 1893–94 by Louis Sullivan. Despite these developments in America, Paris architects and clients showed little interest in building tall office buildings. Paris was already the most densely populated city in Europe, it was already the banking and financial capital of the continent, and moreover, as of 1889 it had the tallest structure in the world, the Eiffel Tower. Beside the Eiffel Tower, The skyline of Paris presented the Arc de Triomphe, the dome of the Basilca of Sacre Coeur, the Arc de Triomphe, and numerous church domes, towers and spires. While some Paris architects visited Chicago to see what has happening, no clients wanted to change the familiar skyline of Paris. [15]

The new office buildings of the Belle Époque often made use of steel, plate glass, elevators and other new architectural technologies, but they were hidden inside sober neoclassical stone facades, and the buildings matched the height of the other buildings on Haussmann's boulevards. The Saint-Gobain glass company built a new headquarters on Place des Saussaies in the 8th arrondissement in the 1890s. Since the firm had been founded under Louis XIV in 1665, the facade of the building, designed by architect Paul Noël, was perfectly modern on the inside, but had architectural touches from the earlier century; colossal columns, a square dome, and beautifully detailed sculptural ornament.

Dramatic glass domes became a common feature of Belle Époque commercial and office buildings in Paris; they provided abundant light when gaslight was a common fire hazard and electric lights were primitive. They followed the example of the central book storeroom of the Bibliothèque Nationale by Henri Labrouste in 1863 and the skylight of Bon Marché department store by Louis-Charles Boileau in 1874. The architect Jacques Hermant (1855–1930) had a purely classical training; he won the Prix de Rome from the Ecole des Beaux Arts in 1880 but he was also fascinated by modern ideas. in 1880 had traveled to Chicago to see the new office buildings there, and he designed an innovative iron frame for the Hall of Civil Engineering at the Exposition of 1900. Between 1905 and 1911, he built the spectacular glass dome of the headquarters of Société générale at 29 Boulevard Haussmann. [16]

The headquarters of the bank Crédit lyonnais, built in 1883 on the boulevard des Italiens in 1883 by William Bouwens Van der Boijen, was classical on the outside, but inside one of the most modern buildings of its time, using an iron frame and glass skylight to provide ample light to large hall where the title deeds were held. In 1907 the building was updated with a new entrance at 15 rue du Quatre-Septembre, designed by Victor Laloux, who also designed the Gare d'Orsay, now the Musée d'Orsay The new entrance featured a striking rotunda with a glass dome over a floor of glass bricks, which allowed the daylight to illuminate the level below, and the three other levels below. The entrance was badly damaged by a fire in 1996; the rotunda was restored, but the only a few elements still remain of the titles hall.[17]

The new Sorbonne

One of the two stairways to the Grand Amphitheater of the Sorbonne

One of the two stairways to the Grand Amphitheater of the Sorbonne Panorama of the Grand Amphitheater, decorated with murals of the history of the university.

Panorama of the Grand Amphitheater, decorated with murals of the history of the university..jpg) The Salle Saint-Jacques, the reading room of the Sorbonne library (1897)

The Salle Saint-Jacques, the reading room of the Sorbonne library (1897)

One of the most prestigious building projects of the Belle Époque was the reconstruction of a new building for the Sorbonne, replacing the crumbling and overcrowded buildings of the old university, while preserving the spirit and tradition of the architecture of the 17th century. The competition in 1882 was won by a little-known architect, Henri-Paul Nénot, who was only twenty-nine years old. He was a graduate of the École des Beaux-Arts, and had worked for various architects, including Charles Garnier. The principal feature of the building is the Grand Amphitheater, at 47 rue des Écoles. Nénot placed the most striking features of the building in the interior, in the vestibule with its great arches and its two symmetrical stairways leading to the balconies and to the grand hall of the Council of the University, placed under a cupola completely open up to the second floor. He gave great attention to the secondary spaces, not just the main rooms, and to the different perspectives created as visitors climbed the stairways. A starkly modern skylight fills the amphitheater with light. The openness of the interior architecture also illuminates and highlights the murals which illustrate the history of the university.

The first part of the project was carried out in the 1880s. The second part, in the 1890s, was creating new facades and an arcade around the great courtyard at 17 rue de la Sorbonne, which looked out on the chapel. Nénot preserved some of the motifs of the old buildings, and a few original architectural features, such as the large sundial which decorated the facade central building on the courtyard. The facades were simplified and given a greater clarity and harmony, while preserving the essential spirit of the 17th century architecture. [18] The Salle Saint-Jacques, the reading room of the Sorbonne library, with its arched ceiling and walls decorated in the pure Beaux-arts style, was completed in 1897.[19]

Churches and synagogues

.jpg) The Basilica of Sacré-Coeur, designed by Paul Abadie, built between 1874 and 1914

The Basilica of Sacré-Coeur, designed by Paul Abadie, built between 1874 and 1914 The Eglise Saint-Jean-de-Montmartre, by Anatole de Baudot (1894)

The Eglise Saint-Jean-de-Montmartre, by Anatole de Baudot (1894) Interior of the Église Saint-Jean-de-Montmartre

Interior of the Église Saint-Jean-de-Montmartre- The church of Notre-Dame-du-Travail, built for the construction workers of the 1900 Exposition (1897–1902)

Exterior of the rue Pavée Synagogue, by Hector Guimard (1913)

Exterior of the rue Pavée Synagogue, by Hector Guimard (1913)- Interior of the Synagogue on Rue Pavée, with its discreet Art Nouveau detail

Most of the churches in the early period of the Belle Époque were constructed in an eclectic or historical style; the most prominent example was the Basilica of Sacré-Coeur on Montmartre, designed by Paul Abadie. His project was chosen by the archbishop after a competition of seventy-eight different projects. Abedie was an expert on romanesque, medieval and Byzantine architecture, and in historical restoration; he had worked with Viollet-le-Duc on the restoration of the Cathedral of Notre-Dame in the 1840s. His design was a combination of neo-Romanesque and neo-Byzantine styles, similar to the domes of the 12th century Cathédrale Saint-Front in Perigueux, which Abadie had helped restore, and which he modified considerably in the restoration. The construction of the Basilica lasted from 1874 until 1914, thanks in part to problems in constructing on Montmartre, which was riddled by tunnels used for mining gypsum, used to make plaster for Paris buildings. Abadie died in 1884, well before the work was finished. The consecration of the church was delayed by the First World War, and did not take place until 1919. [20]

Later in the period, at the end of the 20th century, some architects tried to develop a new forms and a new aesthetic, using modern materials. The best example was the Église Saint-Jean-de-Montmartre, begun in 1894 by architect Anatole de Baudot. Baudot was an expert in medieval architecture, and was a pupil of Viollet-le-Duc. He was professor at the École de Chaillot, which trained the architects in the restoration of historical monuments, as well as professor of medieval architecture at the École des Beaux-Arts. In his project for the new church, he combined the gothic with the Art Nouveau. He commissioned some of the major artists of the Art Nouveau, including ceramics artist Alexandre Bigot, ironwork craftsman Émile Robert, and sculptor Pierre Roche. It was the first church in Paris to be built of reinforced concrete, and Some features, particularly the facades of the sides, were highly original. The result was a curious combination of the gothic and modernism. The leading figure of modernist architecture in the 1920s, Corbusier, was particularly outraged by the church and described it as "hideous".[21]

Another original design was that of the Église-de-Notre-Dame-du-Travail in the 14th arrondissement, by architect Jules Astruc, built between 1897 and 1902. It replaced a smaller church in the parish, and was designed for the large numbers of construction workers who had come to Paris to work on the 1900 Exposition and who settled in the neighborhood. While the exterior of the church is a simple and unadorned Romanesque style, the interior the iron framework was openly and dramatically on display.[22]

In 1913 Hector Guimard designed the Agoudas Hakehilos Synagogue at 10 rue de Paveé in the Marais neighborhood. It was built for the Union of Orthodox Jews, as a place of worship for the large number of Jewish refugees coming from Russia and eastern Europe at the turn of the century. Like his other late art nouveau buildings, it had very little ornament on the outside; its originality was expressed in the undulations of its vertical lines. The interior was slightly more decorative, with all the luminaries, brackets, iron railings and vegetal decoration designed by Guimard himself. On the eve of Yom Kippur in 1941, during the German occupation, it was dynamited, along with six other Paris Mosques, badly damaging the facade, but was restored. The new facade, particularly the gable over the entrance, is slightly more curved and ornate than the original. [23]

Hotels

The Céramic Hôtel, at 34 avenue de Wagram, by architect Jules Lavirotte (1905)

The Céramic Hôtel, at 34 avenue de Wagram, by architect Jules Lavirotte (1905) Facade of the Céramic Hôtel, covered with ceramic decoration and sculpture by Camille Alaphilippe.

Facade of the Céramic Hôtel, covered with ceramic decoration and sculpture by Camille Alaphilippe. The Hotel Lutetia (1910), designed by Louis-Charles Boileau, originally designed for wealthy customers of the Bon Marché department store

The Hotel Lutetia (1910), designed by Louis-Charles Boileau, originally designed for wealthy customers of the Bon Marché department store

The Céramic Hôtel at 14 avenue de Waggram in the 8th arrondissement, was built in 1905 by the architect Jules Lavirotte, with sculpture by Camille Alaphilippe. Like the residential building designed by Lavirotte, the reinforced concrete facade is almost completely covered with decoration made by the ceramics studio of Alexandre Bigot. It won the municipal competition for best facade in 1905.

The most prominent hotel built in the Art Nouveau style is the Hotel Lutetia, built in 1910 at 45 Boulevard Raspail. It was constructed by the owners of the Le Bon Marché department store, on the other side of Square Boucicault. It was originally built by the owners of the department store as a place to stay for the wealthy customers coming from out of town. The architect was Louis-Charles Boileau, who also enlarged the department store. The facade remains Art Nouveau, but the interior was remodeled later to Art Deco.

Cafés and restaurants

An Art Nouveau private dining room by Henri Sauvage from the Café de Paris (1899), now in the Musée Carnavalet

An Art Nouveau private dining room by Henri Sauvage from the Café de Paris (1899), now in the Musée Carnavalet Train Bleu Restaurant in the Gare de Lyon (1902). It looked out from the station facade on one side, and onto the train platform on the other.

Train Bleu Restaurant in the Gare de Lyon (1902). It looked out from the station facade on one side, and onto the train platform on the other. The restaurant Pré Catalan in the Bois de Boulogne (1905), like department stores of the period, had plate glass windows from floor to ceiling. Painting by Alexandre Gervex (1909).

The restaurant Pré Catalan in the Bois de Boulogne (1905), like department stores of the period, had plate glass windows from floor to ceiling. Painting by Alexandre Gervex (1909).

The architecture and decor of Paris restaurants closely followed the styles of the day. The most characteristic restaurant of the Belle Époque style still in existence is the Train Bleu restaurant, designed by Marius Toudoire as the station buffet when it opened in 1902. The lavishly decorated interior is in the style of the 1900 Exposition, the event for which the station was built. The light coming through the large arched windows out the facade on one side, and onto the platform from which trains depart on the other.

The classic Art Nouveau style was used by architect Henri Sauvage in 1899 when he designed an intimate private dining room for the Café de Paris, The furnishings were designed in forms imitating nature, plants and flowers. The Café was demolished in 1950, and nothing remains but these furnishings, which are now on display in the Musée Carnavalet.

The most classical and at the same time the most original restaurant design of the period belonged to the Restaurant of the Pré Catalan, located in the Pré Catalan gardens of the Bois de Boulogne. The building, designed by Guillaume Tronchet in 1905. was in the style of the Petit Trianon of Louis XVI, with one major exception; the walls were almost entirely of large sheets of plate glass, from the floor to the ceiling, in the style of the new Paris department stores. The diners inside could look out at the gardens, while those outside could watch the diners within. A 1909 painting of the restaurant by Henri Gervex, Un soirée au Pré-Catalan, captured the modern spirit of the restaurant. The diners inside the restaurant in the painting include the aviation pioneer Santos-Dumont and the Marquis de Dion, one of the first automobile constructors. [24]

Metro station entrances

_Porte_Dauphine_Paris_16e_002.jpg)

In 1899 the company building the new Paris Metro system, the Compagnie du chemin de fer métropolitain de Paris (CMP), held a competition for the design of the new edicules, or station entrances, to be built around the city. The rules of the competition required that the new edicules "should not make ugly or impede the public way around the stations; on the contrary, they should amuse the eye and decorate the sidewalks."[25] Guimard, considered the most audacious architect of the period, won the competition. The unique style of his stations made them easily recognizable from a distance, one of the important requirements of the competition. He designed a whole series of different variations, ranging from small and simple railing of a stairway to a large pavilion for the Place de la Bastille. Guimard's entrances, with their color, material and form, were in harmony with the stone buildings of the Paris streets, and even, with their vegetal curves, fit well with trees and gardens. They were not used in certain locations, such as place de l'Opera, where they would have looked out of place next to the enormous monuments. The design and construction of the entrances was done by another architect, Joseph Cassien-Bernard (1848–1926).

The entrances were admired at first, but tastes changed, and in 1925 the entrance at the Place de la Concorde was demolished and replaced with a simpler, classical entrance. Gradually, almost all of the Guimard entrances were replaced. Today, there are only three original edicules. The edicule at Porte Dauphine is the only one still in its original place; the edicule at Abbesses was at the Hotel de Ville until 1974; and the edicule at Place du Châtelet was recreated in 2000 to celebrate the centenary of the Metro system.

Railroad stations

Gare de Lyon, by architect Marius Toudoire (1895–1902).

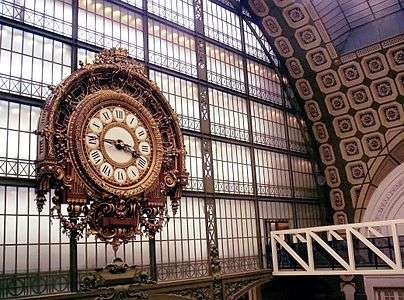

Gare de Lyon, by architect Marius Toudoire (1895–1902). The clock of the Gare d'Orsay, by Victor Laloux

The clock of the Gare d'Orsay, by Victor Laloux Interior of the Gare d'Orsay (now the Musée d'Orsay) in about 1900.

Interior of the Gare d'Orsay (now the Musée d'Orsay) in about 1900.

The main railroad stations of Paris predated the Belle Époque, but they were enlarged and lavishly decorated to impress the visitors to the Expositions of 1889 and 1900. The Gare Saint-Lazare featured a grand shelter for the trains forty meters high, built between 1851 and 1853 by Eugène Flachat, and memorably captured in the impressionist paintings of Claude Monet in 1877. It was enlarge and redecorated for the 1889 Exposition by Juste Lisch, who also designed the neighboring Hotel Terminus. The Gare du Nord, by architects Reynaud and Jacques Ignace Hittorff, was finished in 1866, but expanded in 1889 for the 1900 Exposition. The Gare de l'Est first built between 1847 and 1850, it was tripled in size between 1895 and 1899 to welcome Exposition visitors. The Gare Montparnasse, first built in 1840 on Avenue du Maine for the Paris-Versailles line, was moved to its present location between 1848 and 1852, and then enlarged and redecorated between 1898 abad 1900 for the 1900 Exposition.

The Gare de Lyon, originally built for the line Paris-Monterau in 1847, was completely rebuilt between 1895 and 1902 by architect Marius Toudoire (1852–1922) and the engineering firm of Denis, Carthault and Bouvard. Unlike the earlier stations, which had traditional neoclassical facades attached to the modern structure of the train shed. Toudoire chose to give the Gare de Lyon a facade different from other public buildings; it had a series of monumental arches with doorways opening to arcades within the station. The spaces between the arches were decorated with sculpture. Above that level was an even more unusual element; a strong horizontal band of windows. The tower with an enormous clock was another unusual feature, unlike any other train station or historical model in the city.[26] The interior features included a buffet later named the Train Bleu, in the most lavish Belle Époque style.[27]

The Gare d'Austerlitz, or Gare d'Orleans, was inaugurated in 1843 and enlarged between 1846 and 1852. In 1900 the same company decided to build a new station, the Gare d'Orsay, closer to the center of the city and to the Exposition. It was the first station designed to accommodate electric trains, and it was intended to contain a hotel as well as a train station; the hotel was placed where the museum entrance is today. The original design for the station called for a Renaissance style facade similar to that of Haussmann's buildings on the boulevards. The City of Paris wanted something more monumental to match the grandeur Louvre across the Seine, but also wanted it to clearly express its function as a train station. The city required that a competition be held, which was won by Victor Laloux. His winning design included a feature similar to the Gare de Lyon; he opened the side of the station facing the Seine with very high arches filled with windows, and facade above the windows was decorated with sculptures and emblems. The huge clock became an integral part of the facade. [28] The new station was inaugurated on July 4, 1900, just in time for the Exposition. As a train station It was not a commercial success, and was planned for demolition in 1971, but was saved and between 1980 and 1986, it was transformed into a museum of 19th century French art, the Musée d'Orsay.[29]

Bridges

The Pont Alexandre-III (1896–1900)

The Pont Alexandre-III (1896–1900) The Viaduc d'Austerlitz, built for Paris Metro by Jean-Camille Formigé (1903–1904)

The Viaduc d'Austerlitz, built for Paris Metro by Jean-Camille Formigé (1903–1904) The Pont de Bir-Hakeim by Jean-Camille Formigé (1905)

The Pont de Bir-Hakeim by Jean-Camille Formigé (1905)

Eight new bridges were built across the Seine between 1876 and 1905; the Pont Sully, (1876), to the Ile-Saint-Louis, replacing two footbridges from 1836; the Pont de Tolbiac (1882); the Pont Mirabeau in 1895; the Pont Alexandre-III (1900), built for the 1900 Exposition; the Pont de Grenelle-Passy (1900) for the railroad; the Passerelle Debilly, a footbridge connecting sites of the 1900 Exposition on the two banks; the Pont de Bir-Hakeim (1905), built which carried both pedestrians and a metro line; and the Viaduc d'Austerlitz, used by the Metro.[30]

The most elegant and famous of the Belle Époque bridges is the Pont Alexandre-III, designed by architects Joseph Cassien-Bernard and Gaston Cousin, and engineers Jean Résal and Amédée d'Alby. It was largely decorative, designed to connect the Grand Palais and Petit Palais of the Exposition on the right bank with the parts of the Exposition the left bank. The first stone was laid by Nicholas II of Russia, the future Czar, in October 1896. The bridge combined the modern engineering of a single iron span bridge 107 meters long with classical beaux-arts architecture. The counterweights supporting the bridge are four massive masonry columns, seventeen meters high, which serve as the bases for four works of beaux-arts sculpture, representing the four "Fames"; the Sciences, the Arts, Commerce, and Industry. In the center, the sides of the bridge are decorated with two groups of river nymphs; the Nymphs of the Seine on one side, the Nymphs of the Neva on the other. A similar bridge, the Trinity Bridge, designed by Gustave Eiffel, was built over the Neva River in the Russian Capital, St. Petersburg, beginning in 1897.[31]

The Viaduc d'Austerlitz was an even greater engineering challenge; It was built in 1903–1904 to carry Line 5 of the Paris Metro over the Seine. Because of the nature of the river, it had to be single span, 140 meters long; it was the longest bridge in Paris until 1996, when the Pont Charles-de-Gaulle was built. The architect was Jean-Camille Formigé, the chief of public works of Paris, whose other works included the Greenhouses of Auteuil. As chief of historical monuments of France, he was also responsible for the restoration of the Roman theater at Orange and the Roman amphitheater of Arles. Formigé faced the task of designing a massive bridge which would fit with the monumental buildings along the Seine. He wanted to follow the advice given by Charles Garnier, architect of the Paris Opera, in 1886: "Paris should not be transformed into a factory; it should remain a museum." The bridge combined a graceful double arc anchored to four classical buttresses, and richly decorated with iron and stone sculptural details, to harmonize with the other monuments in the center of the city. [32]

His other new bridge, originally the Pont de Passy, now called the Pont de Bir-Hakeim, carries pedestrians and traffic on one level, and a Metro line, supported by slender iron pillars. It also artfully combined an original functional structure with sculpture and decoration. including groups of sculpture where the iron arches met the piers of the bridge, [32]

The birth of Art Deco

The Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in the Art deco style, by Auguste Perret (1911–1912)

The Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in the Art deco style, by Auguste Perret (1911–1912) Lobby decor of Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, with paintings by Maurice Denis

Lobby decor of Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, with paintings by Maurice Denis- Apartment house at 26 Rue Vavin (6th arrondissement) by Henri Sauvage ((1913)

At the end of the Belle Époque, in about 1910, a new style emerged in Paris, Art Deco largely in reaction to the Art Nouveau. The first major architects to use the style were August Perret (1874–1954), and Henri Sauvage (1873–1932). The main principles of the stye were functionality, classicism and architectural coherence. The curved lines and vegetal patterns of art nouveau gave way to the straight line, simple and precise, and rectangles within rectangles. The preferred building material was reinforced concrete. The decoration was no longer part of the structure itself, as in the Art Nouveau; it was attached to the structure, often in sculpted bas-reliefs, as it was in the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. [33]

The first prominent Paris building in the style was the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, (1911–1912) by Auguste Perret, with sculptural decoration by Antoine Bourdelle. The original project was designed by Henri Fivaz. then by Roger Bouvard, and was intended to be in the gardens of the Champs-Élysées, but a change in the regulations of the gardens caused the theater to be moved to 13–15 avenue Montaigne. The owner, Gabriel Astruc, then commissioned the Belgian art-nouveau architect, Henry Van de Velde, painter Maurice Denis and sculptor Antoine Bourdelle. Auguste Perret was added to the project due to his expertise in the new material, reinforced concrete. Van de Velde and Perret were unable to degree on a design, resulting in the withdrawal of Van de Velde. The final basic design was that of Van de Velde, but was transformed by Perret into an entirely new style. The large lobby was particularly remarkable for the way that the form followed the function; The concrete beams of the ceiling and the supporting columns were immediately visible. It was both perfectly classical and surprisingly modern. The modern architectural critic Gilles Plum wrote, "the form seemed the pure consequence of the construction technique; that was the gothic ideal according to Viollet-le-Duc." }. The interior was decorated by a remarkable collection of artists; besides Maurice Denis and Bourdelle, they included Édouard Vuillard and Ker-Xavier Roussel, inspired by classical and mythological themes, as well as by the music of Debussy. [34]

Another architect at the end of the Belle Epoque whose work heralded the new art deco style was Henri Sauvage. In 1913 he constructed an apartment block at 26 rue Vavin in the 6th arrondissement, for a group of artists and decorators. The exterior was simple and geometric, completely covered with ceramic tiles. the most unusual feature of the buildings were the gradins; the upper floors were arranged like a stairway, which allowed residents on these floors to have terraces and gardens. The only decoration was the iron railings and geometric patterns created by mixing a few black tiles with the white tiles. .[35]

References

Notes and citations

- Sarmant 2012, p. 202.

- Marchand 1993, p. 169.

- Plum 2014, p. 5.

- Stamper, John, Studies in the History of Civil Engineering (2000), Volume 1.

- Plum 2014, p. 14.

- Plum 2014, p. 22.

- Plum 2014, p. 115.

- Lahor 2007, p. 139.

- Plum 2014, p. 44.

- Plum 2014, p. 88.

- Plum 2014, p. 86.

- Naissance des grands magasins : le Bon Marché (by Jacques Marseille, in French, on the official site of the Ministry of Culture of France

- Plum 2014, p. 20.

- Plum 2014, p. 28.

- Plum 2014, pp. 34–35.

- Plum 2014, p. 24.

- Plum 2014, p. 26.

- Plum 1996, pp. 100–103.

- "La bibliothèque de la nouvelle Sorbonne (1897 a now jours)" (in French). Bibliothéque Universitaire Sorbonne. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- Renault 2006, p. 106.

- Plum 2014, p. 104.

- "Église de Notre-Dame-du-Travail in the Merimee data base of historic monuments" (in French). French Ministry of Culture. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- Plum 2014, p. 132.

- Plum 2014, pp. 30–31.

- From Émile Rivoalen, Concours des edicules du metropolitan, in La Construction moderne, August 19, 1899. Cited in Plum, Paris - architectures de la Belle Époque, p. 126.

- Plum 2014, pp. 122–23.

- Fierro 1996, pp. 900–901.

- Plum 2014, p. 120.

- Fierro 1996, p. 900.

- Fierro 1996, p. 1088.

- "Alexandre III Bridge". Structurae—International Database for Civil and Structural Engineering. Wilhelm Ernst & Sohn Verlag. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- Plum 2014, p. 128.

- Renault 2006, pp. 112–113.

- Plum 2014, p. 136.

- Plum 2014, p. 76.

Bibliography

- Combeau, Yvan (2013). Histoire de Paris. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. ISBN 978-2-13-060852-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fierro, Alfred (1996). Histoire et dictionnaire de Paris. Robert Laffont. ISBN 2-221-07862-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)}

- Héron de Villefosse, René (1959). HIstoire de Paris. Bernard Grasset.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)}

- Jarrassé, Dominique (2007). Grammaire des Jardins Parisiens. Paris: Parigramme. ISBN 978-2-84096-476-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)}

- Lahor, Jean (2007). L'Art Nouveau. Baseline Co. LTD. ISBN 978-1-85995-667-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)}

- Le Roux, Thomas (2013). Les Paris de l'industrie 1750–1920. CREASPHIS Editions. ISBN 978-2-35428-079-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)}

- Marchand, Bernard (1993). Paris, histoire d'une ville (XIX-XX siecle). Éditions du Seuil. ISBN 2-02-012864-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)}

- Plum, Gilles (2014). Paris architectures de la Belle Époque. Éditions Parigramme. ISBN 978-2-84096-800-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)}

- Renault, Christophe (2006). Les Styles de l'architecture et du mobilier. Editions Jean-Paul Gisserot. ISBN 978-2-877474-658.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)}

- Sarmant, Thierry (2012). Histoire de Paris: Politique, urbanisme, civilisation. Editions Jean-Paul Gisserot. ISBN 978-2-755-803303.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)}

- Du Camp, Maxime (1870). Paris: ses organes, ses fonctions, et sa vie jusqu'en 1870. Monaco: Rondeau. ISBN 2-910305-02-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)}

- Dictionnaire Historique de Paris. Le Livre de Poche. 2013. ISBN 978-2-253-13140-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)}

- Petit Robert - Dictionnaire universal des noms propres. Le Robert. 1988.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)}