Victor Contamin

Victor Contamin (1840–1893) was a French structural engineer, an expert on the strength of materials such as iron and steel. He is known for the Galerie des machines of the Exposition Universelle (1889) in Paris. He also pioneered the use of reinforced concrete.

Victor Contamin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1840 Paris, France |

| Died | 1893 |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Structural engineer |

| Known for | Galerie des machines |

Career

Victor Contamin was born in Paris in 1840. He was admitted to the École centrale des arts et manufactures in Paris in 1857, and graduated in second place in 1860.[1] One of his teachers was Jean-Baptiste-Charles-Joseph Bélanger, a disciple of Gaspard-Gustave Coriolis. Bélanger treated Contamin with great affection, and gave him much advice when he left the school.[2]

Contamin's first work experience was in Spain. [1] In 1863, he joined the Chemins de Fer du Nord railway company as a designer, attached to the department responsible for the tracks. He was successively promoted to Inspector, Engineer (1876), and Chief Engineer (1890).[1] He also taught the course on Applied Mechanics at the École centrale from 1865 to 1873, and then held the chair of Applied Resistance[lower-alpha 1] until 1891.[1][3] In 1874 Contamin published a textbook entitled Cours de résistance appliquée.[4]

As a recognized expert on the strength of materials, in 1886 Contamin was made responsible for control of metal structures in the 1889 exposition. He was to study all plans and projects in terms of the strength requirements for the buildings. He was also responsible for checking receipt of materials, strength testing, and monitoring the erection of iron structures.[1] His approval of the quality of the materials, workshop production and on-site work was required for release of public funds.[1] As he noted in a letter to La revue le Travail in December 1888, the importance of this work was often not appreciated by the public.[5]

Contamin and his team checked all the calculations and all the metal installations, including the 300 metres (980 ft) tower that Gustave Eiffel was building.[1] He said of the Eiffel Tower:[lower-alpha 2]

The flag that is flying from the summit of the tower is the flag of '89,[lower-alpha 3] the one with which our ancestors have won great victories fighting for progress and science. This flag needed a large pedestal, with large dimensions. It was Mr. Eiffel who built it with the help of his dedicated collaborators. We are glad to honor them[6]

Contamin was one of the pioneers of the use of reinforced concrete. He worked with Anatole de Baudot (1834–1915) on a design for the Saint-Jean-de-Montmartre church, Paris, that used this material, built between 1894–1897.[7]

Contamin died in 1893.[8]

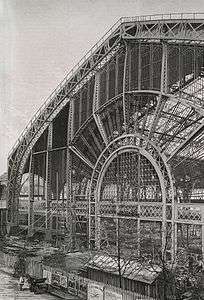

Galerie des Machines

Contamin worked with the architect Ferdinand Dutert (1845–1906) on the design of the Galerie des Machines for the 1889 exposition.[9] Contamin was responsible for the technical design of the Galerie des Machines, including calculations to ensure the structural integrity of the immense arches.[10] The Galerie des machines formed a huge glass and metal hall with an area of 115 by 420 metres (377 by 1,378 ft) and a height of 48.324 metres (158.54 ft). There were no internal supports.[11] The iron and glass structure used three-pin hinged arches, which had been developed for bridge building.[9] This was the first time the portal arch had been used on such a large scale.[12] The Galerie des Machines was re-used for the 1900 exposition, and demolished in 1910.[9]

Many of the writers who discussed the Galerie des Machines gave Victor Contamin much of the credit, since they assumed it was primarily an engineering feat. However, more recently writers have given greater credit to Dutert.[13] Eugène Hénard, who assisted Dutert, said the Palais des Machines successfully combined aesthetic appearance with engineering function. The two goals were complementary.[14]

Gallery

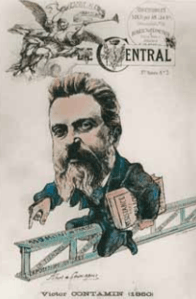

1889 cartoon

1889 cartoon Central Dome of the Galerie des Machines Exposition Universelle de Paris 1889 by Louis Béroud

Central Dome of the Galerie des Machines Exposition Universelle de Paris 1889 by Louis Béroud Side view of the Galerie des Machines

Side view of the Galerie des Machines

References

Notes

- "Resistance" is used in terms of the strength of materials under different conditions.

- "Le drapeau qui flotte au sommet de la Tour est le drapeau de 89, celui avec lequel nos ancêtres ont remporté de grandes victoires en combattant pour le progrès et la science. Pour ce drapeau, il fallait un grand piédestal, avec de grandes dimensions. C'est M. Eiffel qui l'a construit, avec l'aide de dévoués collaborateurs ; nous somme heureux de leur rendre hommage."[6]

- Flag of '89: A reference to the French Revolution of 1789. The exposition was held on the 100th anniversary of the storming of the Bastille.

Citations

- Lagarde-Fouquet 2010, p. 42.

- Belhoste 2008, p. 37.

- Belhoste 2008, p. 72.

- Lorenz 1880, p. 34.

- Lagarde-Fouquet 2010, p. 43.

- Lagarde-Fouquet 2010, p. 41.

- reinforced concrete: TalkTalk.

- Lucan 2009, p. 195.

- Nilsen 2011, p. 101.

- Parville 1890, p. 210.

- Le palais des machines: Chantier, p. 6.

- Langmead & Garnaut 2001, p. 127.

- Glancey 1994.

- Nansouty 1889, p. 116.

Sources

- Belhoste, Jean-Francois (2008). "Les centraliens et al construction metallique de 1830 a 1914". 150 ans de génie civil: Une histoire de centraliens. Presses Paris Sorbonne. ISBN 978-2-84050-569-3. Retrieved 29 May 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Glancey, Jonathan (13 July 1994). "Architecture: Mechanical power and the glory: Jonathan Glancey looks back at the crucible of Modern design in the shadow of the Eiffel tower". The Independent. Retrieved 29 May 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lagarde-Fouquet, Annie (September–October 2010). "Trois Centraliens et un drapeau" (PDF). Centraliens (605). Retrieved 29 May 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Langmead, Donald; Garnaut, Christine (2001). Encyclopedia of Architectural and Engineering Facts. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-112-0. Retrieved 28 May 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Le palais des machines". Les Chantiers de l'Exposition Universelle de 1889. 15 April 1887.

- Lorenz (1880). Catalogue général de la librairie française: 1840–1925. Nilsson, P. Lamm. p. 34. Retrieved 29 May 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lucan, Jacques (2009). Composition, non-composition: Architecture et théories, XIXe-XXe siècles. Presses polytechniques et universitaires romandes. ISBN 978-2-88074-789-3. Retrieved 28 May 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nansouty, Max de (1889). "Le Palais des Machines". Revue rose (in French). Germer Bailliére. Retrieved 25 May 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nilsen, Micheline (2011). Architecture in Nineteenth-Century Photographs: Essays on Reading a Collection. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4094-0904-5. Retrieved 28 May 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Parville, Henri de (1890). L'Exposition universelle [1889]. J. Rothschild. p. 208. Retrieved 26 May 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "reinforced concrete". TalkTalk. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

External links

- The Palais des Machines of 1889. Historical - structural reflections Paper written by Isaac López César & Javier Estévez Cimadevila about the structure of The Galerie des Machines