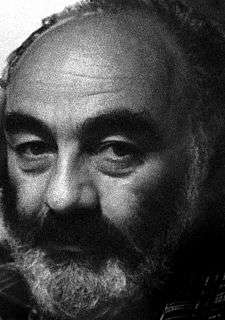

Sergei Parajanov

Sergei Parajanov (Armenian: Սերգեյ Փարաջանով; Russian: Серге́й Ио́сифович Параджа́нов; Georgian: სერგო ფარაჯანოვი; Ukrainian: Сергій Йо́сипович Параджа́нов; sometimes spelled Paradzhanov or Paradjanov; January 9, 1924 – July 20, 1990) was a Soviet film director and artist of Armenian descent who made significant contribution to world cinema with his films Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors and The Color of Pomegranates.[1] He invented his own cinematic style,[2] which was totally out of step with the guiding principles of socialist realism (the only sanctioned art style in the USSR). This, combined with his controversial lifestyle and behaviour, led Soviet authorities to repeatedly persecute and imprison him, and suppress his films. Despite this, Parajanov was named one of the 20 Film Directors of the Future [3] by the prestigious Rotterdam International Film Festival, and his films were ranked among the greatest films of all time by the British Film Institute's magazine Sight & Sound.[4][5]

Sergei Parajanov | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Sarkis Hovsepi Parajaniants January 9, 1924 |

| Died | July 20, 1990 (aged 66) |

| Resting place | Komitas Pantheon, Yerevan |

| Occupation | Director, screenwriter, art director, production designer |

| Years active | 1951–1990 |

Notable work |

|

| Spouse(s) | Nigyar Kerimova (1950–1951) Svetlana Tscherbatiuk (1956–1962) |

| Children | Suren Parajanov (1958–) |

| Website | www.parajanov.com |

Although he started professional film-making in 1954, Parajanov later disowned all the films he made before 1965 as "garbage". After directing Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (renamed Wild Horses of Fire for most foreign distributions) Parajanov became something of an international celebrity and simultaneously a target of attacks from the system. Nearly all of his film projects and plans from 1965 to 1973 were banned, scrapped or closed by the Soviet film administrations, both local (in Kiev and Yerevan) and federal (Goskino), almost without discussion, until he was finally arrested in late 1973 on charges of rape, homosexuality and bribery. He was imprisoned until 1977, despite a pleas for pardon from various artists. Even after his release (he was arrested for the third and last time in 1982) he was a persona non grata in Soviet cinema. It was not until the mid-1980s, when the political climate started to relax, that he could resume directing. Still, it required the help of influential Georgian actor Dodo Abashidze and other friends to have his last feature films greenlighted. His health seriously weakened by four years in labor camps and nine months in prison in Tbilisi, Parajanov died of lung cancer in 1990, at a time when, after almost 20 years of suppression, his films were being featured at foreign film festivals. In January 1988, he said in an interview, "Everyone knows that I have three Motherlands. I was born in Georgia, worked in Ukraine and I'm going to die in Armenia."[6] Sergei Parajanov is buried at Komitas Pantheon in Yerevan.[7]

Parajanov's films won prizes at Mar del Plata Film Festival, Istanbul International Film Festival, Nika Awards, Rotterdam International Film Festival, Sitges - Catalan International Film Festival, São Paulo International Film Festival and others. Parajanov's most comprehensive retrospective in the UK took place in 2010 at BFI Southbank, the BFI's London flagship venue. The retrospective was curated by Layla Alexander-Garrett and contemporary art curator and Parajanov specialist Elisabetta Fabrizi (BFI Head of Exhibitions) who also commissioned a Parajanov-inspired new commission in the BFI Gallery by contemporary artist Matt Collishaw ('Retrospectre'). A symposium was dedicated to Paradjanov's ouvre bringing together world experts to discuss and celebrate the director's contribution to cinema and art.[8]. The director's retrospective was the best grossing season at BFI Southbank in the 2010-11 financial year.

Early life and films

Parajanov was born Sarkis Hovsepi Parajaniants (Սարգիս Հովսեփի Փարաջանյանց) to artistically gifted Armenian parents, Iosif Paradjanov and Siranush Bejanova, in Tbilisi, Georgia. (The family name of Parajaniants is attested by a surviving historical document at the Sergei Parajanov Museum in Yerevan.)[9] He gained access to art from an early age. In 1945, he traveled to Moscow, enrolled in the directing department at the VGIK, one of the oldest and highly respected film schools in Europe, and studied under the tutelage of directors Igor Savchenko and Aleksandr Dovzhenko.

In 1948 he was convicted of homosexual acts (which were illegal at the time in the Soviet Union) with a MGB officer named Nikolai Mikava in Tbilisi. He was sentenced to five years in prison, but was released under an amnesty after three months.[10] In video interviews, friends and relatives contest the truthfulness of anything he was charged with. They speculate the punishment may have been a form of political retaliation for his rebellious views.

In 1950 Parajanov married his first wife, Nigyar Kerimova, in Moscow. She came from a Muslim Tatar family and converted to Eastern Orthodox Christianity to marry Parajanov. She was later murdered by her relatives because of her conversion. After her murder Parajanov left Russia for Kiev, Ukraine, where he produced a few documentaries (Dumka, Golden Hands, Natalia Uzhvy) and a handful of narrative films: Andriesh (based on a fairy tale by the Moldovan writer Emilian Bukov), The Top Guy (a kolkhoz musical), Ukrainian Rhapsody (a wartime melodrama), and Flower on the Stone (about a religious cult infiltrating a mining town in the Donets Basin). He became fluent in Ukrainian and married his second wife, Svitlana Ivanivna Shcherbatiuk (1938-2020[11]), also known as Svetlana Sherbatiuk or Svetlana Parajanov, in 1956. Shcherbatiuk gave birth to a son, Suren, in 1958.[12] The couple eventually divorced and she and Suren relocated to Kiev, Ukraine.[11]

Break from Soviet Realism

Andrey Tarkovsky's first film Ivan's Childhood had an enormous impact on Parajanov's self-discovery as a filmmaker. Later the influence became mutual, and he and Tarkovsky became close friends. Another influence was Italian filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini, who Parajanov would later describe as "like a God" to him and a director of "majestic style".[13] In 1965 Parajanov abandoned socialist realism and directed the poetic Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, his first film over which he had complete creative control. It won numerous international awards and, unlike the subsequent The Color of Pomegranates, was relatively well received by the Soviet authorities. The Script Editorial Board at Goskino of Ukraine praised the film for "conveying the poetic quality and philosophical depth of M. Kotsiubynsky’s tale through the language of cinema," and called it "a brilliant creative success of the Dovzhenko studio." Moscow also agreed to Goskino of Ukraine's request to release the film with its original Ukrainian soundtrack intact, rather than redub the dialogue into Russian for Soviet-wide release, in order to preserve its Ukrainian flavor.[14] (Russian dubbing was standard practice at that time for non-Russian Soviet films when they were distributed outside the republic of origin.)

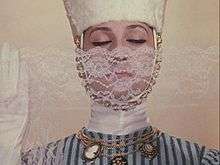

Parajanov departed Kiev shortly afterwards for his ancestors' homeland, Armenia. In 1969, he embarked on Sayat Nova, a film that many consider to be his crowning achievement, though it was shot under relatively poor conditions and had a very small budget.[15] Soviet censors intervened and banned Sayat Nova for its allegedly inflammatory content. Parajanov re-edited his footage and renamed the film The Color of Pomegranates. Critic Alexei Korotyukov remarked: "Paradjanov made films not about how things are, but how they would have been had he been God." Mikhail Vartanov wrote in 1969 that "Besides the film language suggested by Griffith and Eisenstein, the world cinema has not discovered anything revolutionarily new until The Color of Pomegranates ...".[16]

Imprisonment and later work

By December 1973, the Soviet authorities had grown increasingly suspicious of Parajanov's perceived subversive proclivities, particularly his bisexuality, and sentenced him to five years in a hard labor camp in Siberia for "a rape of a Communist Party member, and the propagation of pornography."[17] Three days before Parajanov was sentenced, Andrei Tarkovsky wrote a letter to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, asserting that "In the last ten years Sergei Paradjanov has made only two films: Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors and The Colour of Pomegranates. They have influenced cinema first in Ukraine, second in this country as a whole, and third in the world at large. Artistically, there are few people in the entire world who could replace Paradjanov. He is guilty – guilty of his solitude. We are guilty of not thinking of him daily and of failing to discover the significance of a master." An eclectic group of artists, filmmakers and activists protested, to little avail, on behalf of Parajanov, among them Yves Saint Laurent, Françoise Sagan, Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, Luis Buñuel, Federico Fellini, Michelangelo Antonioni, Andrei Tarkovsky and Mikhail Vartanov.

Parajanov served four years out of his five-year sentence, and later credited his early release to the efforts of the French Surrealist poet and novelist Louis Aragon, the Russian poet Elsa Triolet (Aragon's wife), and the American writer John Updike.[15] His early release was authorized by Leonid Brezhnev, General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, presumably as a consequence of Brezhnev's chance meeting with Aragon and Triolet at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow. When asked by Brezhnev if he could be of any assistance, Aragon requested the release of Parajanov, which was effected by December 1977.[17]

While he was incarcerated, Parajanov produced a large number of miniature doll-like sculptures (some of which were lost) and some 800 drawings and collages, many of which were later displayed in Yerevan, where the Sergei Parajanov Museum is now permanently located.[18] (The museum, opened in 1991, a year after Parajanov’s death, hosts more than 200 works as well as furnishings from his home in Tbilisi.) His efforts in the camp were repeatedly compromised by prison guards, who deprived him of materials and called him mad, their cruelty only subsiding after a statement from Moscow admitted that "the director is very talented."[15]

After his return from prison to Tbilisi, the close watch of Soviet censors prevented Parajanov from continuing his cinematic pursuits and steered him towards the artistic outlets he had nurtured during his time in prison. He crafted extraordinarily intricate collages, created a large collection of abstract drawings and pursued numerous other avenues of non-cinematic art, sewing more dolls and some whimsical suits.

In February 1982 Parajanov was once again imprisoned, on charges of bribery, which happened to coincide with his return to Moscow for the premiere of a play commemorating Vladimir Vysotsky at the Taganka Theatre, and was effected with some degree of trickery. Despite another stiff sentence, he was freed in less than a year, with his health seriously weakened.[17]

In 1985, the slow thaw within the Soviet Union spurred Parajanov to resume his passion for cinema. With the encouragement of various Georgian intellectuals, he created the multi-award-winning film The Legend of Suram Fortress, based on a novella by Daniel Chonkadze, his first return to cinema since Sayat Nova fifteen years earlier. In 1988, Parajanov made another multi-award-winning film, Ashik Kerib, based on a story by Mikhail Lermontov. It is the story of a wandering minstrel, set in the Azerbaijani culture. Parajanov dedicated the film to his close friend Andrei Tarkovsky and "to all the children of the world".

Parajanov then attempted to complete his final project. He died of cancer in Yerevan, Armenia, on July 20, 1990, aged 66, leaving this final work, The Confession, unfinished. It survives in its original negative as Parajanov: The Last Spring (film), assembled by his close friend Mikhail Vartanov in 1992. Federico Fellini, Tonino Guerra, Francesco Rosi, Alberto Moravia, Giulietta Masina, Marcello Mastroianni and Bernardo Bertolucci were among those who publicly mourned his death.[16] They sent a telegram to Russia with the following statement: "The world of cinema has lost a magician".[16]

Influences and legacy

Despite having studied film at the VGIK, Parajanov discovered his artistic path only after seeing Andrei Tarkovsky's dreamlike first film Ivan's Childhood. Parajanov was highly appreciated by Tarkovsky himself in "Voyage in Time" ("Always with huge gratitude and pleasure I remember the films of Sergei Parajanov which I love very much. His way of thinking, his paradoxical, poetical... ability to love the beauty and the ability to be absolutely free within his own vision"), and Michelangelo Antonioni, Francis Ford Coppola, Jean-Luc Godard ("In the temple of cinema, there are images, light, and reality. Sergei Parajanov was the master of that temple"), Martin Scorsese, Mikhail Vartanov ("Probably, besides the film language suggested by Griffith and Eisenstein, the world cinema has not discovered anything revolutionary new until Paradjanov's Color of Pomegranates"), Federico Fellini, Tonino Guerra, Giulietta Masina, Francesco Rosi, Alberto Moravia, Bernardo Bertolucci, Marcello Mastroianni.[19]

Despite having many admirers of his art, his vision did not attract many followers. "Whoever tries to imitate me is lost", he reportedly said.[20] However, directors such as Theo Angelopoulos, Béla Tarr and Mohsen Makhmalbaf share Parajanov's approach to film as a primarily visual medium rather than as a narrative tool.[21]

The Parajanov-Vartanov Institute was established in Hollywood in 2010 to study, preserve and promote the artistic legacies of Sergei Parajanov and Mikhail Vartanov.[22]

Filmography

| Year | English title | Original title | Romanization | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1951 | Moldavian Tale | (in Russian) Молдавская сказка (in Ukrainian) Moлдавська байка | Moldavskaya Skazka | Graduate short film; lost |

| 1954 | Andriesh | (in Russian) Андриеш | Andriesh | Co-directed with Yakov Bazelyan; feature-length remake of Moldavian Tale |

| 1958 | Dumka | (in Ukrainian) Думка | Dumka | Documentary |

| 1958 | The First Lad (aka The Top Guy) | (in Russian) Первый парень (in Ukrainian) Перший пapyбок | Pervyj paren | |

| 1959 | Natalya Ushvij | (in Russian) Наталия Ужвий | Natalia Uzhvij | Documentary |

| 1960 | Golden Hands | (in Russian) Золотые руки | Zolotye ruki | Documentary |

| 1961 | Ukrainian Rhapsody | (in Russian) Украинская рапсодия (in Ukrainian) Yкpaїнськa Paпсодія | Ukrainskaya rapsodiya | |

| 1962 | Flower on the Stone | (in Russian) Цветок на камне (in Ukrainian) Цвіток на камені | Tsvetok na kamne | |

| 1965 | Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors | (in Ukrainian) Тіні забутих предків | Tini zabutykh predkiv | |

| 1965 | Kiev Frescoes | (in Russian) Киевские фрески | Kievskie Freski | Banned during pre-production; 15 minutes of auditions survive |

| 1967 | Hakob Hovnatanian | (in Armenian) Հակոբ Հովնաթանյան | Hakob Hovnatanyan | Short film portrait of the 19th century Armenian artist |

| 1968 | Children to Komitas | (in Armenian) Երեխաներ Կոմիտասին | Yerekhaner Komitasin | Documentary for UNICEF; lost[23] |

| 1969 | The Color of Pomegranates | (in Armenian) Նռան գույնը | Nran guyne | |

| 1985 | The Legend of Suram Fortress | (in Georgian) ამბავი სურამის ციხისა | Ambavi Suramis tsikhisa | |

| 1985 | Arabesques on the Pirosmani Theme | (in Russian) Арабески на тему Пиросмани | Arabeski na temu Pirosmani | Short film portrait of the Georgian painter Niko Pirosmani |

| 1988 | Ashik Kerib | (in Georgian) აშიკი ქერიბი (in Azerbaijani) Aşıq Qərib | Ashiki Keribi | |

| 1989–1990 | The Confession | (in Armenian) Խոստովանանք | Khostovanank | Unfinished; original negative survives in Mikhail Vartanov's Parajanov: The Last Spring[24][25] |

Screenplays

Produced and partially produced screenplays

- Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (Тіні забутих предків, 1965, co-written with Ivan Chendei, based on the novelette by Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky)

- Kiev Frescoes (Киевские фрески, 1965)

- Sayat Nova (Саят-Нова, 1969, production screenplay of The Color of Pomegranates)

- The Confession (Исповедь, 1969–1989)

- Studies About Vrubel (Этюды о Врубеле, 1989, depiction of Mikhail Vrubel's Kiev period, co-written and directed by Leonid Osyka)

- Swan Lake: The Zone (Лебедине озеро. Зона, 1989, filmed in 1990, directed by Yuriy Illienko, cinematographer of Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors)

Unproduced screenplays and projects

- The Dormant Palace (Дремлющий дворец, 1969, based on Pushkin's poem The Fountain of Bakhchisaray)

- Intermezzo (1972, based on Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky's short story)

- Icarus (Икар, 1972)

- The Golden Edge (Золотой обрез, 1972)

- Ara the Beautiful (Ара Прекрасный, 1972, based on the poem by 20th century Armenian poet Nairi Zaryan about Ara the Beautiful)

- Demon (Демон, 1972, based on Lermontov's eponymous poem)

- The Miracle of Odense (Чудо в Оденсе, 1973, loosely based on the life and works of Hans Christian Andersen)

- David of Sasun (Давид Сасунский, mid-1980s, based on Armenian epic poem David of Sasun)

- The Martyrdom of Shushanik (Мученичество Шушаник, 1987, based on Georgian chronicle by Iakob Tsurtaveli)

- The Treasures of Mount Ararat (Сокровища у горы Арарат)

Among his projects, there also were plans for adapting Longfellow's The Song of Hiawatha, Shakespeare's Hamlet, Goethe's Faust, the Old East Slavic poem The Tale of Igor's Campaign, but film scripts for these were never completed.

References in popular culture

Parajanov's life story provides (quite loosely) the basis for the 2006 novel Stet by the American author James Chapman.

See also

References

- Sergei Parajanov, Biography at IMDB

- Sergei Parajanov, Biography at Parajanov-Vartanov Institute

- 20 Film Directors of the Future

- The Greatest Films of all time

- Parajanov and the Greatest Films of all time

- Parajanov Interview

- Parajanov's memorial tombstone at Komitas Pantheon

- Fabrizi, Elisabetta, 'The BFI Gallery Book', BFI, London, 2011.

- Sergei Paradzhanov and Zaven Sarkisian, Kaleidoskop Paradzhanov: Risunok, kollazh, assambliazh (Yerevan: Muzei Sergeiia Paradzhanova, 2008), p.8

- Segodnya.ua

- (in Ukrainian) The wife of the legendary director Sergei Parajanov has died, Glavcom (6 June 2020)

- Suren Parajanov

- Paradjanov: A Requiem (Documentary). KINO Productions. 1994.

- RGALI (Russian State Archive of Art and Literature), Goskino production and censorship files: f. 2944, op. 4, d. 280.

- Sergei Parajanov – Interview with Ron Holloway, 1988 Archived 2007-12-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Parajanov.com

- Осужден за изнасилование члена КПСС (in Russian), Moskovskiy Komsomolets, 2004 Archived 2007-08-10 at Archive.today

- Frieze Magazine, Paradjanov the Magnificent Archived 2008-04-16 at the Wayback Machine

- See official page.

- The Moscow Times

- Parajanov Influence

- Parajanov-Vartanov Institute Archived 2014-10-22 at Archive-It

- Parajanov's lost film

- Parajanov: The Last Spring

- Schneider, Steven. "501 Movie Directors" London: Cassell, 2007, ISBN 9781844035731

Bibliography

Selected bibliography of books and scholarly articles about Sergei Parajanov.

English language sources

- Dixon, Wheeler & Foster, Gwendolyn. "A Short History of Film." New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2008. ISBN 9780813542690

- Cook, David A. "Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors: Film as Religious Art." Post Script 3, no. 3 (1984): 16–23.

- Nebesio, Bohdan. "Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors: Storytelling in the Novel and the Film." Literature/Film Quarterly 22, no. 1 (1994): 42–49.

- Oeler, Karla. "A Collective Interior Monologue: Sergei Parajanov and Eisenstein's Joyce-Inspired Vision of Cinema." The Modern Language Review 101, no. 2 (April 2006): 472-487.

- Oeler, Karla. "Nran guyne/The Colour of Pomegranates: Sergo Parajanov, USSR, 1969." In The Cinema of Russia and the Former Soviet Union, 139-148. London, England: Wallflower, 2006. [Book chapter]

- Papazian, Elizabeth A. "Ethnography, Fairytale and ‘Perpetual Motion’ in Sergei Paradjanov’s Ashik- Kerib." Literature/Film Quarterly 34, no. 4 (2006): 303–12.

- Paradjanov, Sergei. Seven Visions. Edited by Galia Ackerman. Translated by Guy Bennett. Los Angeles: Green Integer, 1998. ISBN 1892295040, ISBN 9781892295040

- Parajanov, Sergei, and Zaven Sarkisian. Parajanov Kaleidoscope: Drawings, Collages, Assemblages. Yerevan: Sergei Parajanov Museum, 2008. ISBN 9789994121434

- Steffen, James. The Cinema of Sergei Parajanov. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2013. ISBN 9780299296544

- Steffen, James, ed. Sergei Parajanov special issue. Armenian Review 47/48, nos. 3–4/1–2 (2001/2002). Double issue; publisher website

- Steffen, James. "Kyiv Frescoes: Sergei Parajanov’s Unrealized Film Project." KinoKultura Special Issue 9: Ukrainian Cinema (December 2009), online. URL: http://www.kinokultura.com/specials/9/steffen.shtml

- Schneider, Steven Jay. "501 Movie Directors." London: Hachette/Cassell, 2007. ISBN 9781844035731

Foreign language sources

- Bullot, Érik. Sayat Nova de Serguei Paradjanov: La face et le profil. Crisnée, Belgium: Éditions Yellow Now, 2007. (French language) ISBN 9782873402129

- Cazals, Patrick. Serguei Paradjanov. Paris: Cahiers du cinéma, 1993. (French language) ISBN 9782866421335,

- Chernenko, Miron. Sergei Paradzhanov: Tvorcheskii portret. Moskva: "Soiuzinformkino" Goskino SSSR, 1989. (Russian language) Online version

- Grigorian, Levon. Paradzhanov. Moscow: Molodaia gvardiia, 2011. (Russian language) ISBN 9785235034389,

- Grigorian, Levon. Tri tsveta odnoi strasti: Triptikh Sergeia Paradzhanova. Moscow: Kinotsentr, 1991. (Russian language)

- Kalantar, Karen. Ocherki o Paradzhanove. Yerevan: Gitutiun NAN RA, 1998. (Russian language)

- Katanian, Vasilii Vasil’evich. Paradzhanov: Tsena vechnogo prazdnika. Nizhnii Novgorod: Dekom, 2001. (Russian language) ISBN 9785895330425

- Liehm, Antonín J., ed. Serghiej Paradjanov: Testimonianze e documenti su l’opera e la vita. Venice: La Biennale di Venezia/Marsilio, 1977. (Italian language)

- Mechitov, Yuri. Sergei Paradzhanov: Khronika dialoga. Tbilisi: GAMS- print, 2009. (Russian language) ISBN 9789941017544

- Paradzhanov, Sergei. Ispoved’. Edited by Kora Tsereteli. St. Petersburg: Azbuka, 2001. (Russian language) ISBN 9785267002929

- Paradzhanov, Sergei, and Garegin Zakoian. Pis’ma iz zony. Yerevan: Fil’madaran, 2000. (Russian language) ISBN 9789993085102

- Schneider, Steven Jay. "501 Directores de Cine." Barcelona, Spain: Grijalbo, 2008. ISBN 9788425342646

- Tsereteli, Kora, ed. Kollazh na fone avtoportreta: Zhizn’–igra. 2nd ed. Nizhnii Novgorod: Dekom, 2008. (Russian language) ISBN 9785895330975

- Vartanov, Mikhail. "Sergej Paradzanov." In "Il Cinema Delle Repubbliche Transcaucasiche Sovietiche." Venice, Italy: Marsilio Editori, 1986. (Italian language) ISBN 8831748947

- Vartanov, Mikhail. "Les Cimes du Monde." Cahiers du Cinéma" no. 381, 1986 (French language) ISSN 0757-8075

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sergei Parajanov. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Sergei Parajanov (Armenian Wikiquote) |

- Official Site (Parajanov.com)

- Sergej Parajanov Museum

- Sergei Parajanov on IMDb

- Hollywood Reporter

- Deadline Hollywood

- The Moscow Times

- ENCI.com

- The Parajanov Case, March 1982

- Sergei Parajanov's 75th birthday

- The Cinemaseekers Honor Roll

- Museum of Sergei Parajanov on GoYerevan.com

- Interview with Ron Holloway

- Film about Parajanov Museum in Yerevan on YouTube

- Actress Sofiko Chiaureli and many others about him

- Arts: Armenian Rhapsody

- Excerpted from "Paradjanov’s Films on Soviet Folklore" by Jonathan Rosenbaum

- For those who want to know more about Parajanov

- The Color of Pomegranates on YouTube

- TV channel in Los Angeles on Sergei Parajanov on YouTube

- Evening Moscow Newspaper Spouses of Sergei Parajanov and Mikhail Vartanov received awards in Hollywood

- Sergei Parajanov. Collages. Graphics. Works of Decorative Art. Kyiv, 2008.