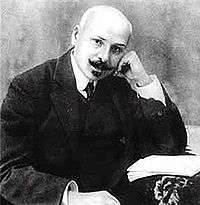

Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky

Mykhailo Mykhailovych Kotsiubynsky (Ukrainian: Михайло Михайлович Коцюбинський), (September 17, 1864 – April 25, 1913) was a Ukrainian author whose writings described typical Ukrainian life at the start of the 20th century. Kotsiubynsky's early stories were described as examples of ethnographic realism; in the years to come, with his style of writing becoming more and more sophisticated, he evolved into one of the most talented Ukrainian impressionist and modernist writers.[1] The popularity of his novels later led to some of them being made into Soviet movies.

Mykhailo Mykhailovych Kotsiubynsky Михайло Михайлович Коцюбинський | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 17, 1864 Vinnytsia, Russian Empire |

| Died | April 25, 1913 (aged 48) Chernihiv, Russian Empire |

| Pen name | Zakhar Kozub |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Nationality | Ukrainian |

| Spouse | Vira Ustymivna Kotsiubynska |

| Children | Yuriy, Oksana |

| Signature |  |

Life

He grew up in Bar, Vinnytsia region and several other towns and villages in Podolia, where his father worked as a civil servant. He attended the Sharhorod Religious Boarding School from 1876 until 1880. He continued his studies at the Kamianets-Podilskyi Theological Seminary, but in 1882 he was expelled from the school for his political activities within the socialist movement. Already he had been influenced by the awakening Ukrainian national idea. His first attempts at writing prose in 1884 were also written in the Ukrainian language: Andriy Soloviyko(Ukrainian: Андрій Соловійко).

Early work and research

From 1888 to 1890, he was a member of the Vinnytsia Municipal Duma. In 1890, he visited Galicia, where he met several other Ukrainian cultural figures including Ivan Franko and Volodymyr Hnatiuk. It was there in Lviv that his first story Nasha Khatka (Ukrainian: Наша хатка) was published.

During this period, he worked as a private tutor in and near Vinnytsia. There, he could study life in traditional Ukrainian villages, which was something he often came back to in his stories including the 1891 Na Viru (Ukrainian: На віру) and the 1901 Dorohoiu tsinoiu (Ukrainian: Дорогою ціною).

During large parts of the years 1892 to 1897, he worked for a commission studying the grape pest phylloxera in Bessarabia and Crimea. During the same period, he was a member of the secret Brotherhood of Taras.

He moved to Chernihiv in 1898 where he worked as a statistician at the statistics bureau of the Chernihiv zemstvo. He also was active in the Chernigov Governorate Scholarly Archival Commission and headed the Chernihiv Prosvita society from 1906 to 1908.

Writings

After the Russian Revolution of 1905, Kotsiubynsky could be more openly critical of the Russian tsarist regime, which can be seen in Vin ide (Ukrainian: Він іде) and Smikh (Ukrainian: Сміх), both from 1906, and Persona grata from 1907.

Fata Morgana, in two parts from 1904 and 1910, is probably his best-known work. Here he describes the typical social conflicts in the life of the Ukrainian village.

About twenty novels were published during Kotsiubynsky's life. Several of them have been translated into other European languages.

Death

Because of a heart disease, Kotsiubynsky spent long periods at different health resorts on Capri from 1909 to 1911. During the same period, he visited Greece and the Carpathians. In 1911 he was granted a pension from the Society of Friends of Ukrainian Scholarship, Literature, and Art that enabled him to quit his job and solely concentrate on his writings, but he was already in poor health and died only two years later.

Honors

During the Soviet period, Kotsiubynsky was honoured as a realist and a revolutionary democrat. A literary-memorial museum was opened in Vinnytsia in 1927 in the house where he was born.[4] Later a memorial was created nearby the museum.

The house in Chernihiv where he lived for the last 15 years of his life was turned into a museum in 1934; the Chernihiv Regional Literary-Memorial Museum of Mykhailo Kotsiubinsky. The house contains the author’s personal belongings. Adjacent to the house is a museum, which opened in 1983, containing Kotsiubinsky’s manuscripts, photos, magazines and family relics as well as information about other Ukrainian writers.[5]

Several Soviet movies have been based on Kotsiubynsky’s novels such as Koni ne vynni (1956), Dorohoiu tsunoiu (1957) and Tini zabutykh predkiv (1967).[4]

Family

In January 1896, he married Vira Ustymivna Kotsiubynska (Deisha) (1863–1921).[6]

One of his sons, Yuriy Mykhailovych Kotsiubynsky (1896–1937), was the Bolshevik and the Red Army commander during the 1917–1921 Civil War. Later, he held several high positions within the Communist Party of Ukraine, but in 1935, he was expelled from the party. In October 1936, he was accused of having counter-revolutionary contacts and together with other Bolsheviks have organized a Ukrainian Trotskyist Centre. The year after, he was sentenced to death and executed. He was rehabilitated in 1955.[7] Yuri had a son Oleh.[8]

His daughter Oksana Kotsyubynska was married to Vitaliy Primakov.

The fate of his other children Roman and Iryna is less known.

His niece, Mykhailyna Khomivna Kotsiubynska (1931), is the Ukrainian philologist and literary specialist. She is an honorary doctor of the Kyiv Mohyla Academy.

References

- "Kotsiubynsky, Mykhailo". Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Retrieved 2011-01-01.

- Kotsyubynsky, M., 1998, Brother against Brother, pp.293-322, Language Lantern Publications, Toronto, (Engl. transl.)

- Kotsyubynsky, M., 1976, Fata Morgana, Dnipro, Kyiv, (Engl. transl.)

- Encyclopedia of Ukraine

- Chernihiv Tourist Informationcenter Archived 2012-04-26 at the Wayback Machine

- Ihor Siundiukov: The socio-esthetic ideal through the eyes of Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky. Den 2002, # 38.

- Yuriy Oleksandrovych Smyrnov & Petro Petrovych Mykhailenko Militsiia Ukraïny: istorychnyi narys, portrety, podiï, Vydavnychyi dim "In Yure", Kiev 2002.

- Profile at personalities

See also

- Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky Shadow of Ukrainian History

- Michailo Kotsiubinskij: Berättelser från Ukraina. Bokförlagsaktiebolaget Svithiod, Stockholm 1918.

- Ukraine. A Concise Encyclopædia, vol 1, p. 1032–1033. University of Toronto Press 1963.

- 100 znamenytykh liudey Ukraïny, s.204–208. Folio, Kharkiv 2005. ISBN 966-03-2988-1.

- Encyclopedia of Ukraine

- Ihor Siundiukov: The socio-esthetic ideal through the eyes of Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky. Den 2002, # 38.

- Volodymyr Panchenko: “I am better off alone”. Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky’s correspondence with his wife. Den 2005, # 40, 41.

External links

- Works by Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)