Pan-American Exposition

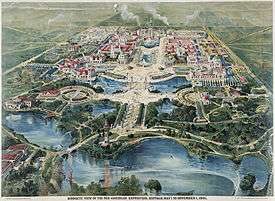

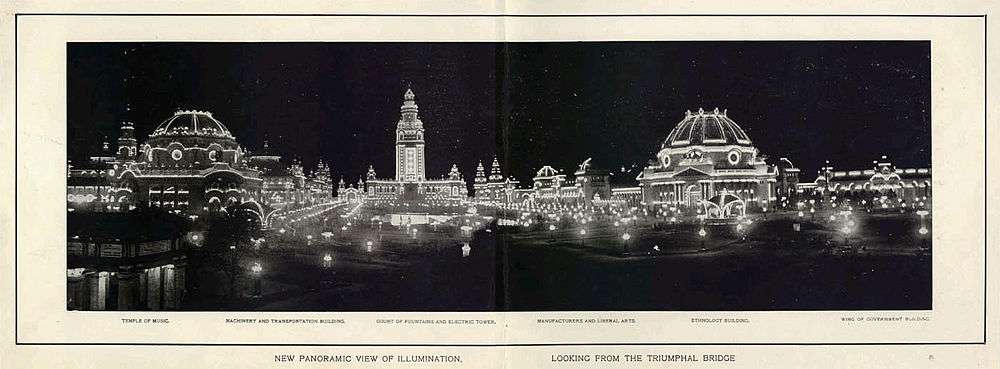

The Pan-American Exposition was a World's Fair held in Buffalo, New York, United States, from May 1 through November 2, 1901. The fair occupied 350 acres (0.55 sq mi) of land on the western edge of what is now Delaware Park, extending from Delaware Avenue to Elmwood Avenue and northward to Great Arrow Avenue. It is remembered today primarily for being the location of the assassination of United States President William McKinley at the Temple of Music on September 6, 1901. The exposition was illuminated at night. Thomas A. Edison, Inc. filmed it during the day and a pan of it at night.[1][2][3]

| Pan-American Exposition | |

|---|---|

Official logo by Raphael Beck | |

| Overview | |

| BIE-class | Unrecognized exposition |

| Name | Pan-American Exposition |

| Area | 350-acre |

| Visitors | 8,000,000 |

| Location | |

| Country | United States of America |

| City | Buffalo, New York |

| Timeline | |

| Opening | May 1, 1901 |

| Closure | November 2, 1901 |

| expositions | |

| Previous | Trans-Mississippi Exposition in Omaha, Nebraska |

| Next | Inter-State and West Indian Exposition in Charleston, South Carolina |

History

The event was organized by the Pan-American Exposition Company, formed in 1897. Cayuga Island was initially chosen as the place to hold the Exposition because of the island's proximity to Niagara Falls, which was a huge tourist attraction. When the Spanish–American War broke out in 1898, plans were put on hold. After the war, there was a heated competition between Buffalo and Niagara Falls over the location. Buffalo won for two main reasons. First, Buffalo had a much larger population—with roughly 350,000 people, it was the eighth-largest city in the United States. Second, Buffalo had better railroad connections—the city was within a day's journey by rail for over 40 million people. In July 1898, Congress pledged $500,000 for the Exposition to be held at Buffalo. The "Pan American" theme was carried throughout the event with the slogan "commercial well being and good understanding among the American Republics." The advent of the alternating current power transmission system in the US allowed designers to light the Exposition in Buffalo using power generated 25 miles (40 km) away at Niagara Falls.

Assassination of President McKinley

The exposition is most remembered because United States President William McKinley was assassinated by an anarchist, Leon Czolgosz, at the Temple of Music on September 6, 1901. The President died eight days later on September 14 from gangrene caused by the bullet wounds.

On the day prior to the shooting, McKinley had given an address at the exposition, which began as follows:

Expositions are the timekeepers of progress. They record the world's advancement. They stimulate the energy, enterprise, and intellect of the people; and quicken human genius. They go into the home. They broaden and brighten the daily life of the people. They open mighty storehouses of information to the student.[4]

The newly developed X-ray machine was displayed at the fair, but doctors were reluctant to use it on McKinley to search for the bullet because they did not know what side effects it might have had on him. Also, the operating room at the exposition's emergency hospital did not have any electric lighting, even though the exteriors of many of the buildings were covered with thousands of light bulbs. Doctors used a pan to reflect sunlight onto the operating table as they treated McKinley's wounds.

Buildings and exhibits

Buildings and exhibits featured at the Pan-American Exposition included:[5]

| Image | Building | Architect | Status | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Agricultural, Manufacturers, and Liberal Arts Buildings | George Shepley | Demolished | The Agriculture building faced the Court of Fountain.[6] |

|

Electric Tower | John Galen Howard | Demolished | The fair's center piece |

|

Electricity Building | Green & Wicks | Demolished | |

|

Ethnology Building | George Cary | Demolished | |

|

U.S. Government Building | James Knox Taylor | Demolished | The building occupied the entire eastern Esplanade of the Exposition grounds.[7] |

|

Machinery and Transportation Building | Green & Wicks | Demolished | |

|

Mines, Forestry and Graphic Arts Buildings | Robert Swain Peabody | Demolished | The buildings were the first series of buildings a visitor encountered after passing through the Triumphal Bridge.[8] |

|

New York State Building | George Cary | Extant | Constructed of Vermont Marble. |

| Service Building | Esenwein & Johnson | Demolished | First building completed on the grounds.[9] | |

|

Stadium | Babb, Cook & Willard | Demolished | Modeled after the Panathenaic Stadium.[10] |

|

Temple of Music | Esenwein & Johnson | Demolished | Center for the live performances |

|

Woman's Building | Demolished | Former club house of the Country Club of Buffalo.[11] | |

|

Fair Japan | Demolished | Organized by Kushibiki and Arai. |

Attractions

- The Court of Fountains, the central court to the exposition.

- The Great Amphitheater

- The Triumphal Bridge, which was positioned over the "Mirror Lake".

- Joshua Slocum's sloop, the Spray, on which he had recently sailed around the world alone.

- A Trip to the Moon, a mechanical dark ride that was later housed at Coney Island's Luna Park.

- In the center of the rose-garden beside the Woman's Building was Enid Yandell's "Struggle of Existence," a plaster version of the fountain "Struggle of Life" installed in Rhode Island

Lina Beecher, creator of the Flip Flap Railway, attempted to demonstrate one of his looping roller coasters at the fair, but the organizers of the event considered the ride to be too dangerous and refused to allow it on the grounds.[12] Buffalo native Nina Morgana, later a soprano with the Metropolitan Opera, was a child performer in the "Venice in America" attraction at the Exposition.[13]

Demolition

When the fair ended, the contents of the grounds were sold to the Chicago House Wrecking Company[14] of Chicago for US$92,000 ($2.46 million in 2019 dollars[15]).[16] Demolition of the buildings began in March 1902, and within a year, most of the buildings were demolished. The grounds were then cleared and subdivided to be used for residential streets, homes, and park land. Similar to previous world fairs, most of the buildings were constructed of timber and steel framing with precast staff panels made of a plaster/fiber mix. These buildings were built as a means of rapid construction and temporary ornamentation and not made to last.[17] Prior to its demolition, an effort was made via public committee to purchase and preserve the original Electric Tower from the wrecking company for nearly US$30,000 ($922 thousand in 2019 dollars[15]). However, the necessary funding could not be raised in time.[16]

The site of the exposition was bounded by Elmwood Avenue on the west, Delaware Avenue on the east, what is now Hoyt Lake on the south, and the railway on the north. It is now occupied by a residential neighborhood from Nottingham Terrace to Amherst Street, and businesses on the north side of Amherst Street. A stone and marker on a traffic island dividing Fordham Drive, near the Lincoln Parkway, marks the area where the Temple of Music was located.[18]

Legacy

- The New York State Building, located in Delaware Park, was designed to outlast the Exposition and is now used as a museum by the Buffalo History Museum. Designated a National Historic Landmark in 1987, it can be visited at the corner of Elmwood Avenue and Nottingham Avenue. The Museum's Research Library has an online bibliography of its extensive Pan-American holdings.[19] Included in the Library collection are the records of the Pan-American Exposition Company.[20]

- The Albright-Knox Art Gallery was intended to serve as a Fine Arts Pavilion but due to construction delays, it was not completed in time.

- The original Electric Tower, although demolished, was the inspiration and design prototype for the 13 story, Beaux-Arts Electric Tower, built in 1912, in downtown Buffalo. The Hotel Statler was likewise demolished before Statler built a replacement in 1907, then another replacement in 1923.

- A boulder marking the site of McKinley's assassination was placed in a grassy median on Fordham Drive in Buffalo.[21]

- At least one engine from the miniature railway that carried visitors around the fair was preserved. It is currently privately owned and operated in Braddock Heights, Maryland.

Statistics

- Ticket Cost: US$0.50

($15.00 in 2019 dollars[15]). - Total Event Expense: US$7 million[22]

($215 million in 2019 dollars[15]) - Visitors: 8,000,000[22]

See also

- Put Me Off at Buffalo – popular song used to advertise the Exposition

- List of world's fairs

- Louisiana Purchase Exposition

- Raphael Beck

- World's Columbian Exposition

- List of world expositions

- International Fair Association Grounds

References

- https://www.loc.gov/item/00694344/

- https://www.loc.gov/item/00694346/

- https://www.loc.gov/item/00694340/

- "The Last Speech of William McKinley". American Experience – America 1900 – Primary Sources. PBS; WGBH Educational Foundation. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- Arnold, Charles (1901). Official Views of Pan-American Exposition. Arnold. Retrieved 2011-08-06.

- "Agriculture Building Design". panam1901.org. Pan-American Exposition Buffalo 1901. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- "U.S. Government Buildings Design". panam1901.org. Pan-American Exposition Buffalo 1901. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- "Mins Building Design". panam1901.org. Pan-American Exposition Buffalo 1901. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- "Service Building Design". panam1901.org. Pan-American Exposition Buffalo 1901. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- Heverin, Aaron (December 14, 1998). "The Architecture". buffalohistoryworks. Archived from the original on June 19, 2012. Retrieved November 6, 2012.

- "Women's Building Design". panam1901.org. Pan-American Exposition Buffalo 1901. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- "Lina Beecher Obituary". Batavia Daily News. October 6, 1915.

- "Nina Morgana ('Little Patti', 'Baby Patti')" Pan-American Women exhibit, University at Buffalo Libraries.

- "Exposition Buildings Sold". San Francisco Call. 24 November 1901. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- "News from 1902 (March)". PanAm1901.org. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- Buffalo's Pan-American Exposition Arcadia Publishing. (1998), page 23. Retrieved 2011-8-5.

- "Quiet Street Enjoys a Place in History", by Anthony Cardinale, Buffalo News, March 12, 1989 pB-11

- Buffalo History Museum. "Pan-American Exposition: A WorldCat List". Worldcat.org. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- Buffalo History Museum. "Finding Aid for the Pan-American Exposition Company Records, 1899-1908". Mss. C65-7: University at Buffalo. Retrieved 4 December 2015.CS1 maint: location (link)

- 42°56′19″N 78°52′25″W, Google Maps Street View of the memorial marker on Fordham Drive.

- Peterson, Harold (2003). "Buffalo Builds the 1901 Pan-American Exposition". Buffalo as History. Retrieved 2011-08-05.

Further reading

- Margaret Creighton (October 18, 2016). Electrifying Fall of Rainbow City: Spectacle and Assassination at the 1901 World's Fair. ISBN 978-0521433365.

- Goodrich, Arthur (August 1901). "Short Stories of Interesting Exhibits". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. II: 1054–1096. Retrieved 2009-07-09.

- Page, Walter H. (August 1901). "The Pan-American Exposition". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. II: 1014–1048. Retrieved 2009-07-09.

- Official catalogue and guide book to the Pan-American Exposition: With Maps of Exhibitions and Illustrations. Buffalo, NY: Charles Ahrhart. 1901.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pan-American Exposition. |

- Doing the Pan: Pan-American Exposition at Buffalo in 1901

- New York Heritage Digital Collections: Pan-American Exposition Scrapbooks

- University at Buffalo Library: Pan-American Exposition of 1901

- University at Buffalo Digital Collections: Pan-American Exposition of 1901

- Pan-American Exposition Company Records: An inventory of the collection in the Research Library at The Buffalo History Museum. The business records are not digitized or online, so an in-person visit is needed to study them.

- Pan-American Exposition: List of Prizes, compiled by The Buffalo History Museum

- Pan-American Exposition Then and Now: A map of the grounds with an overlay of modern streets, created by The Buffalo History Museum

- 1901 Buffalo - approximately 120 links

- The Shapell Manuscript Foundation: Pan-American Exposition souvenir booklet autographed by William McKinley