Luna Park (Coney Island, 1903)

Luna Park was an amusement park in Coney Island, Brooklyn, New York City. Luna Park was located on a site bounded by Surf Avenue to the south, West 8th Street to the east, Neptune Avenue to the north, and West 12th Street to the west. Luna Park opened in 1903 and operated until 1944.

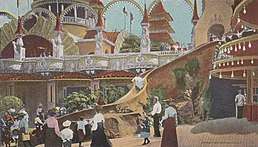

Luna Park entrance, early 20th century | |

| Location | Coney Island, Brooklyn, United States |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40.577°N 73.979°W |

| Owner | Frederic Thompson, Elmer "Skip" Dundy |

| Opened | May 16, 1903[1] |

| Closed | August 13, 1944 |

| Status | Closed |

Luna Park was located partly on the grounds of Sea Lion Park, which operated between 1895 and 1902. It was the second of the three original iconic large parks built on Coney Island, the other two being Steeplechase Park (1897) and Dreamland (1904).[2] The park was mostly destroyed by a fire in 1944, never reopened, and was demolished two years later. Though another amusement park named Luna Park opened nearby in 2010, it has no connection to the 1903 park.

History

Opening

In 1901 the park's creators, Frederic Thompson and Elmer "Skip" Dundy, had created a wildly successful ride called "A Trip To The Moon", as part of the Pan-American Exposition at Buffalo, New York. The name of the fanciful "airship" (complete with flapping wings) that was the main part of the ride was Luna, the Latin word for the moon. The airship, and the later park built around it may have been named after Dundy's sister in Des Moines, Luna Dundy Newman.[3]

At the invitation of Steeplechase Park owner George C. Tilyou, Thompson and Dundy moved their show to Steeplechase, a Coney Island amusement park, for the 1902 season. The deal ended at the end of the summer after Thompson and Dundy rejected Tilyou's contract renewal offer that cut their take of the profits by 20%.

At the end of the 1902 season, Thompson and Dundy signed a long-term lease for Paul Boyton's Sea Lion Park. Sea Lion, the first large scale enclosed park at Coney island, had opened 7 years before. The park had several centerpiece rides but a bad summer season and competition with Steeplechase Park made Boyton decide to get out of the amusement park business. Besides the 16-acre (6.5 ha) Sea Lion Park Thompson and Dundy also leased the adjacent land where the Elephantine Colossus Hotel had stood until it burned down in 1896. This gave them 22 acres (8.9 ha), all the land north of Surf Avenue and south of Neptune Avenue and between W. 8th and W. 12th Street, to build a much larger park.

Thompson and Dundy spent $700,000 (although they advertised it as $1 million) totally rebuilding the park and expanding its attractions. The park's architectural style was an Oriental theme with buildings built on a grand scale and over 1,000 red and white painted spires, minarets and domes. At night all the domes, spires and towers were lit with over 250,000 electric lights. At the center of the park in the middle of a lake was the 200-foot-tall (61 m) Electric Tower that was decorated with twenty thousand incandescent lamps, a smaller version of the Electric Tower that was the crowning feature of the Pan-American Exposition two years earlier. At the base of the tower was a series of cascading fountains. Eventually two circus rings were suspended over the central lagoon to keep customers entertained between rides.

Calling itself "The heart of Coney Island", Luna Park turned on its lights and opened its gates to a crowd of 60,000 spectators precisely at 8:05pm on May 16, 1903, coinciding with the timing of sunset on that Saturday night.[4] Admission to the park was ten cents with rides costing extra, up to 25 cents for the most elaborate rides. The park was accessible from Culver Depot, the terminals of the West End and Sea Beach railroad lines.[5]

Operations

.jpg)

Although Luna Park was a success, competition for visitors ramped up on Coney Island. The next year a third large-scale park called Dreamland opened up.[6]:68 Dreamland featured 4 times as many lights as Luna Park, an even bigger central Tower, and attractions such as "The End of the World", "Feast of Belshazzar and the Destruction of Babylon", and Lilliputia, a miniature village populated by little people. At Coney Island's peak in the middle of the 20th century's first decade, the three amusement parks competed with each other and with many independent amusements.[7]:147–150[8]:11

In 1907, Dundy died leaving Frederic Thompson to run Luna Park until 1912 when he went bankrupt and lost the park to creditors, although he continued as manager.

Luna Park would continue under different management over the years with rides constantly being changed and updated. The Great Depression saw the park go into bankruptcy several times starting in 1933; owners came and went but none seemed to be able to make a profit. Many of the exhibits, rides and shows from the 1939 New York World's Fair moved to Luna Park after the Fair closed and Luna was billed as the New York World's Fair of 1941. With the US entry into World War II Luna was allowed to stay open as a morale booster but had to keep its lights dimmed for wartime security.

| External video | |

|---|---|

Demise

A fire on August 13, 1944 destroyed much of Luna Park, causing $800,000 in damage.[9][10] The park never reopened after the 1944 fire due to legal disputes over the park's insurance money.[11] In August 1946, the park was sold to a company who announced they were going to tear down what was left of Luna Park and build Quonset huts for military veterans and their families.[12] That October, the park was destroyed in another fire.[13]

Rides and attractions

Besides "A Trip to the Moon" Luna Park had many other rides and attractions over the years including:[14]

- "Shoot the Chutes" – a central ride left over from Boynton's Sea Lion Park

- "Carousel"- PTC #66, built by the Philadelphia Toboggan Company and a Wurlitzer #157 Band Organ provided the carousel’s music

- "Bridge of Laughs" – an uneven-surface prank bridge

- "Canals of Venice" – gondola ride

- "Dragon's Gorge" – a scenic railroad trip (opened 1905)

- "The War of the Worlds"

- "The Kansas Cyclone"

- "Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea" (1903–1904)

- "Midnight Express" – miniature railroad

- "Razzle Dazzle"

- "Helter Skelter" – a twisting sliding board

- "Hagenbeck's Wild Animals"

- "Little Egypt" – a show of exotic dancers

- "The Teaser" – spinning wooden chairs

- "The Tickler" (1907) – large round tub that rolled down hill through a winding fence lined path

- "Trip to The North Pole" – Simulated submarine ride to the North Pole that landed patrons in an Eskimo Village

- "Old Mill" – tunnel of love ride

- "Witching Waves" (1907) – small cars propelled by an undulating floor

- "Chinese Theater"

- "Professor Wormwood's Monkey Theater" – trained dogs, monkeys, and apes

- "Infant Incubators" – a display of the new type of infant care

- Trip to the Moon – a roller coaster moved the Coney Island Bowery in 1924 and originally named Drop the Dip.

There were also a "Grand Ballroom", concerts, fireworks, and carnival performances. Thompson and Dundy were constantly changing the park's attractions such as replacing the "20,000 League Under the Sea" in 1905 with the indoor scenic railway called "Dragon's Gorge".[15] Although the building of the park included the infamous publicity stunt where Thompson and Dundy executed Topsy the elephant by electrocution, park owner Dundy became fond of the animals and elephant rides became a feature of the park.

Legacy

In popular culture

- Roscoe Arbuckle's 1917 movie Coney Island features Luna Park.

- The 1928 Oscar-nominated King Vidor movie The Crowd includes a double date sequence filmed at Luna Park.

- Part of Harold Lloyd's 1928 movie Speedy was shot at Luna Park.

- The song "Meet Me Down At Luna, Lena" was recorded by Billy Murray in 1905 to promote the park, among others.[16] The song was rerecorded for the 2007 documentary film Welcome Back Riders.[17]

Namesakes

The original Luna Park site now houses a five-building cooperative apartment complex called Luna Park Houses.[18]

On May 29, 2010 a new amusement park named Luna Park opened at the former site of the defunct Astroland park, a parcel of land on the south side of Surf Avenue just across from the original Luna Park site. The new park, which includes new semi-permanent rides, games, food and beverage concessions, and live entertainment, features an entrance patterned after the entrance to the original 1903 Luna Park.

See also

- Luna Park, list of parks based on the original Luna Park

References

- "Electrocuting an Elephant". The Bendigo Independent (10, 226). Victoria, Australia. May 21, 1903. p. 6 (SUPPLEMENT TO THE BENDIGO INDEPENDENT). Retrieved March 31, 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- David Goldfield, Encyclopedia of American Urban History, SAGE Publications – 2006, page 185

- Pilat, Oliver and Jo Ranson, Sodom By the Sea: An Affectionate History of Coney Island, Garden City: Doubleday, Doran & Co., 1941, p. 146

- David A. Sullivan. "Thompson and Dundy's Luna Park (1903-1944)". www.heartofconeyisland.com. Retrieved February 21, 2016.

- "Map at coneyislandhistory.org". Archived from the original on February 24, 2015. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- Immerso, Michael (2002). Coney Island: the people's playground (illustrated ed.). Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-3138-0.

- Judith N. DeSena; Timothy Shortell (2012). The World in Brooklyn: Gentrification, Immigration, and Ethnic Politics in a Global City. Lexington Books. pp. 147–176. ISBN 978-0-7391-6670-3.

- Parascandola, L.J. (2014). A Coney Island Reader: Through Dizzy Gates of Illusion. Columbia University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-231-53819-0. Retrieved January 20, 2019.

- "HALF OF LUNA PARK DESTROYED BY FIRE AS 750,000 WATCH; Flames Sweep Over 8-Acre Area and Cause $500,000 Loss in 1 1/2-Hour Battle". The New York Times. August 13, 1944. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- "Spectacular Fires on New York Waterfront and Amusement Park". The Examiner. CIII (133). Tasmania, Australia. August 14, 1944. p. 1. Retrieved March 31, 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Luna Park Faces Permanent Eclipse but Memories Remain". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. August 11, 1946. p. 9. Retrieved July 22, 2019 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com

- "Coney's OId Luna Park Will Yield To New Homes for 625 GI Families; LUNA PARK TO BOW TO HOMES FOR GI'S". The New York Times. August 18, 1946. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- "Fire Destroys Luna Park". The News. 47 (7, 229). Adelaide. October 3, 1946. p. 4. Retrieved March 31, 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- Luna Park at Coney Island – A Tribute to Light By Patty Inglish

- Jeffrey Stanton, Coney Island - Luna Park, 1998

- MP3 file

- Welcome Back Riders

- Luna Park Co-op @ Coney Island

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Luna Park (Coney Island, 1903). |

.jpg)