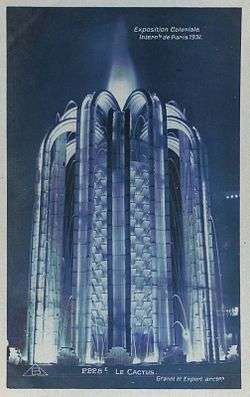

Paris Colonial Exposition

The Paris Colonial Exhibition (or "Exposition coloniale internationale", International Colonial Exhibition) was a six-month colonial exhibition held in Paris, France in 1931 that attempted to display the diverse cultures and immense resources of France's colonial possessions.

History

The exposition opened on 6 May 1931 in the Bois de Vincennes on the eastern outskirts of Paris.[1] The scale was enormous.[2] It is estimated that from 7 to 9 million visitors came from over the world.[3] The French government brought people from the colonies to Paris and had them create native arts and crafts and perform in grandly scaled reproductions of their native architectural styles such as huts or temples.[4] Other nations participated in the event, including The Netherlands, Belgium, Italy, Japan, Portugal, the United Kingdom, and the United States.[2]

Politically, France hoped the exposition would paint its colonial empire in a beneficial light, showing the mutual exchange of cultures and the benefit of France's efforts overseas. This would thus negate German criticisms that France was "the exploiter of colonial societies [and] the agent of miscegenation and decadence". The exposition highlighted the endemic cultures of the colonies and downplayed French efforts to spread its own language and culture abroad, thus advancing the notion that France was associating with colonised societies, not assimilating them.[4]

The Colonial Exposition provided a forum for the discussion of colonialism in general and of French colonies specifically. French authorities published over 3,000 reports during the six-month period and held over 100 congresses. The exposition served as a vehicle for colonial writers to publicise their works, and it created a market in Paris for various ethnic cuisines, particularly North African and Vietnamese. Filmmakers chose French colonies as the subjects of their works. The Permanent Colonial Museum (today the Cité nationale de l'histoire de l'immigration) opened at the end of the exposition. The colonial service experienced a boost in applications.[4]

26 territories of the empire participated in the Colonial Exposition Issue of postage stamps issued in conjunction with the Exposition.

The Dutch colonial pavilion fire incident

As one of important colonial power at that time, the Dutch Empire participated in this grandiose colonial exposition in Paris. The Netherlands presented a beautiful cultural synthesis from their colony; the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia). However, on 28 June 1931, an enormous fire burnt down the Dutch pavilion, along with all cultural objects displayed inside.[5]:43

The Dutch colonial pavilion was located on exhibition lot as wide as 3 hectares and was built based on the combination of many cultural elements of the Nusantara (Indonesian archipelago), a combination of Indonesian vernacular architecture. It has walls consisted of 750,000 pieces of ironwood from Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo). As the centerpiece, the front part is decorated with twin 50 metres-tall Balinese Meru towers. The pavilion's roof was done in tumpang or tajug style, a signature of Javanese mosque, completed with carved wooden door of kori agung typical towering portal of pura Balinese temple, combined with arched roof of Minangkabau's atap bagonjong typical of rumah gadang. This fusion of Indonesian vernacular architecture presented a splendid and majestic palace-like pavilion.[5]:42

Many exquisite cultural objects collected from far-flung Indonesian archipelago was displayed in this pavilion. Those objects among others are; statues of Hindu deities from ancient Java, sword and kris heirloom daggers, jewelries lavished with gemstones, wooden carvings and ornaments of Javanese and Balinese houses, batik fabric of Java, songket fabric from Palembang, ulos from Batak lands, ikat weaving of East Indonesia, paintings and ancient maritime maps, etc. Those collections belongs to the Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen (now National Museum of Indonesia). All of this magnificent display were reflecting the pride of the Netherlands upon their most precious colony, the Dutch East Indies. Arguing that the culture of their colonial subjects was sophisticated, refined and sublime; thus far from the primitive image displayed by other colonial powers in that exhibition.[5]:42

Only a few artefacts could be salvaged from the devastating fire; among others are ancient Javanese bronze Shiva statue, which is now kept in Indonesian National Museum. Until now, the cause of this massive fire is still in debate; short circuit, flammable building materials that was a fire hazzard, to the possibility of an arsonist sabotage, all become wild interpretation circulated at that time. The material and cultural lost was surely immense, estimated around almost 80 million franc. It was said that the French government obliged to paid for loss insurance to the Netherlands Indies colonial government. The money was then used for Bataviaasch Genootschap museum expansion.[5]:43

Communist counter-exhibition

At the request of the Comintern, a smaller counter-exhibition entitled The Truth on the Colonies, organized by the Communist Party and the CGTU, attracted very few visitors (5000 in 8 months).[6] The first section was dedicated to abuses committed during the colonial conquests, and quoted Albert Londres and André Gide's criticisms of forced labour in the colonies while the second one made a comparison of Soviet "nationalities' policy" to "imperialist colonialism".

Posterity

Some of these buildings were preserved or moved:

- Palais de la Porte Dorée, Former-musée national des Arts d'Afrique et d'Océanie, current Cité nationale de l'histoire de l'immigration, porte Dorée in Paris, constructed from 1928 to 1931 by the architects Albert Laprade, Léon Bazin and Léon Jaussely.

- The foundations of the Parc zoologique de Vincennes

- The Pagode de Vincennes, on the edges of the lake Daumesnil, in the former houses of Cameroon and Togo of Louis-Hippolyte Boileau: Photo

- The church Notre-Dame des Missions was moved to Épinay-sur-Seine (95) in 1932.

- The reproduction of Mount Vernon, house of George Washington, moved to Vaucresson where it is still visible.[7]

See also

- French Colonial Empire

- Colonialism

- Human zoo

Notes

- Leininger-Miller 54–5.

- Leininger-Miller 54.

- The figures often given are 29 to 33 million, but those figures are for entries. Given the sale of many tickets allowing multiple entries, it is estimated that the real number was 8 to 9 million visitors, still an impressive figure. Jean Martin. L'Empire triomphant, 1871- 1936, Vol. 2, Paris, Denöel, 1990, p. 417.

- Leininger-Miller 55.

- Endang Sri Hardiati; Nunus Supardi; Trigangga; Ekowati Sundari; Nusi Lisabilla; Ary Indrajanto; Wahyu Ernawati; Budiman; Rini (2014). Trigangga (ed.). Potret Museum Nasional Indonesia, Dulu, Kini dan Akan Datang - Pameran "Potret Museum Nasional Indonesia, Dulu, Kini dan Akan Datang", Museum Nasional Indonesia, 17-24 Mei 2014. Jakarta: National Museum of Indonesia, Directorate General of Culture, Ministry of Education and Culture of the Republic of Indonesia.

- Études coloniales 2006-08-25 "L'Exposition coloniale de 1931 : mythe républicain ou mythe impérial" (in French)

- "The House that Sears Built--in Paris". Sears Homes of Chicagoland. September 28, 2012. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

References

- Leininger-Miller, Theresa A., New Negro Artist in Paris: African American Painters & Sculptors in the City of Light, 1922–1934. Piscataway, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2001.

- Hodeir, Catherine, 1931, l'exposition coloniale. Paris: Editions Complexe, 1991. ISBN 2-87027-382-7.

Further reading

- Morton, Patricia A., Hybrid Modernities: Representation and Architecture at 1931 International Colonial Exposition in Paris. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2000.

- Geppert, Alexander C.T., Fleeting Cities. Imperial Expositions in Fin-de-Siècle Europe, Basingstoke/New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010. ISBN 978-0-230-22164-2.

External links

- Journal de l'Exposition coloniale online in Gallica, the digital library of the BnF

- http://www.sears-homes.com/2012/09/the-house-that-sears-built-in-paris.html about the reproduction of Mount Vernon built for the exposition

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paris Colonial Exposition. |